Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

The coronavirus pandemic has turned the investment world upside down. This isn’t limited to a reduction in the scale of the investment projects, but also involves a revision of the existing business models, primarily based on lowering manufacturing costs by moving the production of major components to locations in the world where labor and raw materials are cheaper. In view of the protectionist sentiments clearly intensifying in many countries, such investments could now turn out to be much more difficult or unprofitable.

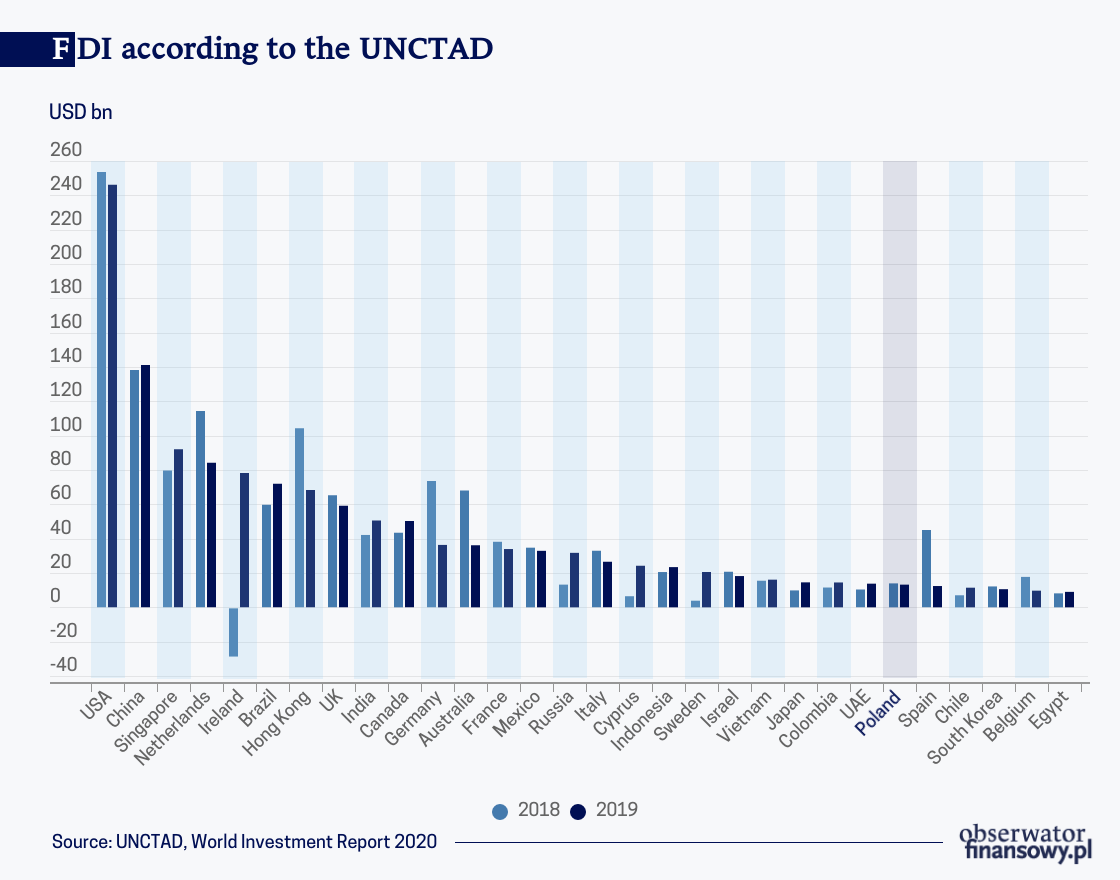

This risk is pointed out in the annual World Investment Report 2020 by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) published in June. The experts at UNCTAD predict that the volume of global FDI will fall from USD1.54 trillion in 2019 to approximately USD900bn, which is the lowest level since 2005. This will constitute a decrease by as much as 60 per cent compared with the highest level recorded in 2015 (more than USD2 trillion). The next year will not be any better, and we should expect a further 5 to 10 per cent reduction in the value of FDIs. Any improvement in this area is unlikely to occur before 2022.

The world’s largest companies initially reacted to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and the introduction of a lockdown by pausing the implementation of investment projects. Over half of the investment costs are financed with previously generated profits. This year, these profits will not materialize, and the prospects for the future remain uncertain.

The current situation is especially affecting large M&A transactions. According to the UNCTAD report as early as in March 2020, the Canadian holding Alimentation Couche-Tard withdrew from the takeover of the Caltex refinery in Australia for USD5.9bn. At the same time, the American self-storage chain Public Storage Inc. abandoned its plans to acquire National Storage, an Australian company with a similar business profile, for USD1.2bn.

In April, the American aviation giant Boeing — which has been ailing not only due to the coronavirus — decided not to acquire the Brazilian company Embraer, the third-largest aircraft manufacturer in the world, for USD4.2bn. Also in April, EQT Holdings Cooperatief, the Dutch holding of consumer companies ranging from health and beauty products to electronics abandoned its plans to acquire (through the Pacific Village Group, its subsidiary company based in the United States) the New Zealand-based financial services company Metlifecare for USD1bn. The lockdown measures introduced by China also prevented the acquisition of casinos in Australia by Melco Resorts & Entertainment from Hong Kong, which operates similar facilities in Macau.

The M&A transactions has been delayed or even suspended not only due to the pandemic, but also as a result of the clear changes in the regulatory policies of governments under the influence of the pandemic. The governments and heads of regulatory institutions of countries in which domestic companies were supposed to be taken over are now more concerned about possible accusations of excessive haste in issuing consent to such sales. This applies in particular to plans of purchases implemented through the stock exchanges in situations where the value of the acquired companies’ shares has significantly decreased. One example of such a transaction, which has been subjected to much stronger scrutiny by the financial supervision authorities (the final consent was ultimately granted by the end of June) was the acquisition of the British company Deliveroo by the American giant Amazon.

According to the latest EY Europe Attractiveness Survey, published in May 2020, 65 per cent of the 6,412 FDI projects announced in 2019 are in place or are proceeding as planned, though with downgraded capacity and recruitment. A further 25 per cent of projects are delayed and 10 per cent are canceled.

Governments all across the world have considerably intensified the regulatory activities in their economies during the pandemic. The main objective is to help domestic companies (especially the smaller ones), to finance entire sectors affected by the crisis (especially the airlines, such as Alitalia, Finnair, Lufthansa, Norwegian Air, as well as hotel chains) and to shorten administrative procedures. On the other hand, new restrictions are being introduced which are targeted against potential foreign investors.

One of the first countries to introduce such restrictions was Spain, which suspended the previously applicable liberal rules concerning the purchase of Spanish companies already in mid-March. At the end of March, the European Commission limited the ability of non-EU residents to invest in European companies involved in the health care sector. A few days later Australia almost completely eliminated the possibility of foreign acquisitions. In early April, the Italian government added finance and insurance to the list of strategically important sectors protected against takeovers. This excludes the possible privatization of such companies with the participation of foreign capital.

Investment restrictions have been introduced all across the world. In mid-April the Indian government — which had only recently allowed foreign investment in the local coal mines — introduced a requirement for an approval of all investment by entities originating from countries sharing a land border with India. It is not difficult to figure out that this measure is mainly targeted at China. Meanwhile, Canada has limited the ability of foreign entities — and especially state-owned companies from other countries — to invest in industries related to health care.

Further restrictions have also been introduced in Europe. France added biotechnology companies to the list of protected sectors. The ownership of more than 10 per cent of their shares will now require the approval of a government agency. Similar restrictions were introduced in Germany, where all companies involved in research, development and production of vaccines and many other medicines will be subjected to protection against foreign acquisitions of shares. Tightened procedures for foreign investors were also introduced by Hungary.

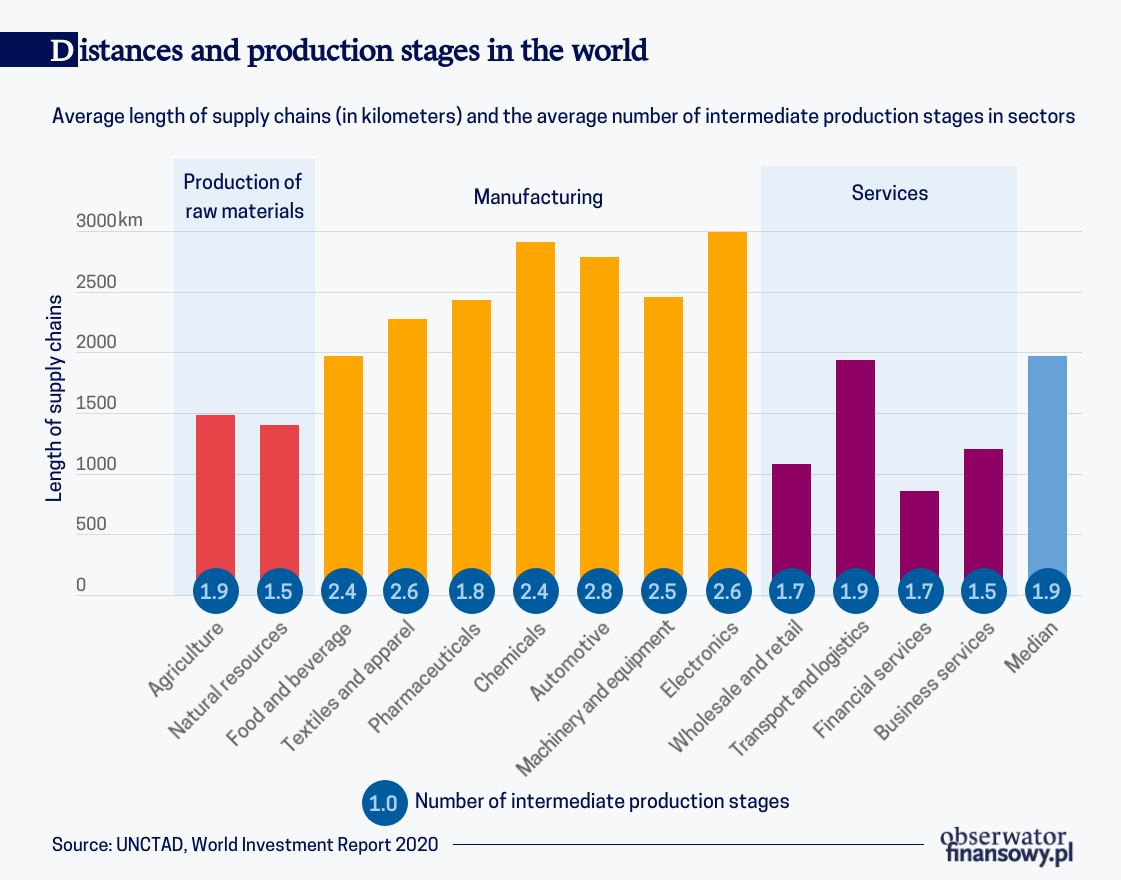

There is some concern that the restrictions on foreign investments will not be temporary. After the pandemic the businesses themselves will also adjust their previous strategy of outsourcing production to places where it is cheaper. The UNCTAD experts predict that in the next decade companies will search for suppliers located closer to their markets and will seek to reduce the physical lengths of the supply chains, which have been increased in the era of globalization. This will be facilitated by the accelerated automation of the most labor-intensive production tasks, which will reduce the importance of lower labor costs — one of the main reasons for the relocation of production to distant countries.

This, in turn, will lead to changes in the geography of investments and the development of individual economies, and especially industries. Such changes will primarily hurt the underdeveloped countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, which have based their growth strategy on attempts to find and then to gradually strengthen their place in the global supply chains. This process has already begun. According to UNCTAD, the decrease in the levels of investment will affect developing countries much more acutely than the developed nations.

The sectors most prone to such changes will be those that currently have the longest — in terms of geographical distance — supply chains. The UNCTAD report shows that electronics could be affected the most, as its production is divided into an average of 2.6 distinct production stages, carried out at distances reaching over 3000 kilometers. The level of global fragmentation is only slightly lower in the production of vehicles, machinery and equipment, chemicals and even textiles and apparel. This is why these sectors were the most affected by the extended closures of borders and transport disruptions following the outbreak of the pandemic.

Poland’s position on the global map of FDI is not particularly significant. According to data provided by UNCTAD, in 2019 the total value of FDI inflows to Poland amounted to USD13.22bn (which is the 25th highest amount of FDI inflows in the world, excluding offshore tax havens). This amount includes the reinvestment of profits generated in Poland. Compared with the previous year, the value of FDI inflows to Poland declined by about USD726.4m. According to EY, in 2019, the FDI in Poland decreased by 26 per cent y/y. Meanwhile, according to NBP data provided in the PLN, in 2019 the total value of FDI amounted to PLN50.8bn.

Regardless of the currency used in the statistics, the volume of FDI in Poland accounts for less than a per cent of the global cross-border investments. However, Poland’s importance as the location of capital investments could increase if the UNCTAD is correct in predicting that after the pandemic large European companies will be looking for new suppliers or establishing new sub-contractors, which will not be as cheap as those in more distant countries, but will be located much closer to the final sales markets. Poland can certainly benefit from this.