Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

The advantages of the railways are indisputable. Unlike cars, trains do not pollute the air to such a great extent. They relieve the roads and reduce congestion. They are also a safer and cheaper means of transport than cars. Experts admit that rail freight is cheaper than transport by trucks, especially for distances exceeding 300 km. This is best confirmed by the United States, a country renowned for its love of cars and pragmatism. While the share of trucks in freight transport is higher than the share of trains, the railway prevails in the case of carriage routes exceeding 700 miles.

Railways also have one more advantage in Poland and in the entire EU, which is highly dependent on oil imports from outside the UE. Trains are powered by electricity, most or even all of which can be produced based on domestic energy resources, such as coal or renewable energy sources. The same can’t be said about car fuels, because we are still very far away from a situation where cars with electric or hydrogen drives dominate the market.

For all the above reasons, the EU authorities have been putting a lot of emphasis on the development of railways for many years. Already in 2011, the European Commission set a goal for the Member States, according to which by 2050 more than half of the road goods transport over distances greater than 300 km should be shifted to other modes of transport – mainly the railways.

This EU policy also results from the fact that rail has been losing importance in Western Europe for several decades (in Poland and Central and Southeast Europe since the 1990s). After the popularization of cars, Europeans preferred to travel using their own vehicles rather than trains, while European companies were increasingly choosing more convenient trucks instead of the railways. A truck is able to pick up a cargo load from any place and deliver it to any desired destination. Which is not the case with trains, as it is usually necessary to reload the goods to trucks and to transport them to the final destination. This, in turn, extends the duration of transport and makes it more expensive. The same is true for passenger transport: unlike a train, a car allows us to reach almost any destination.

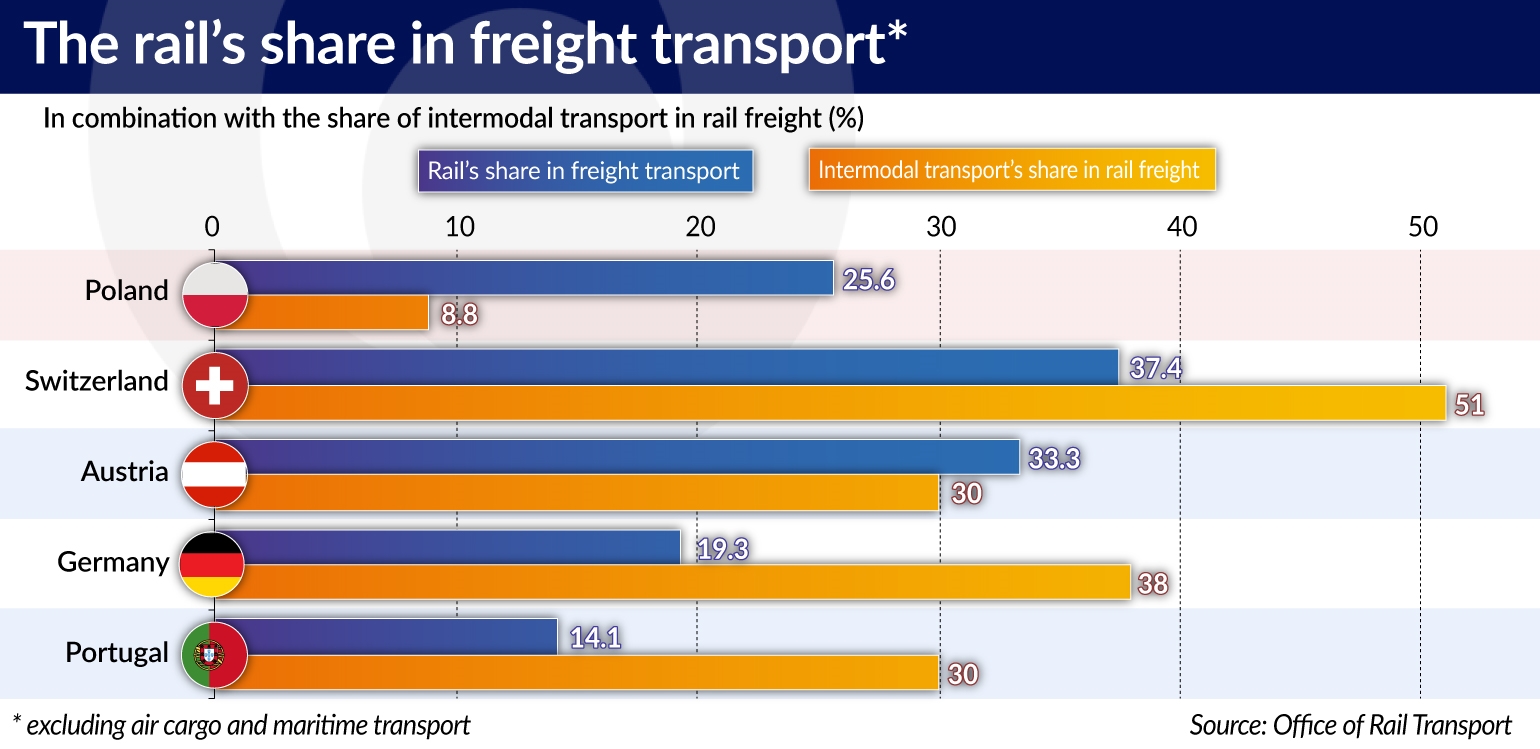

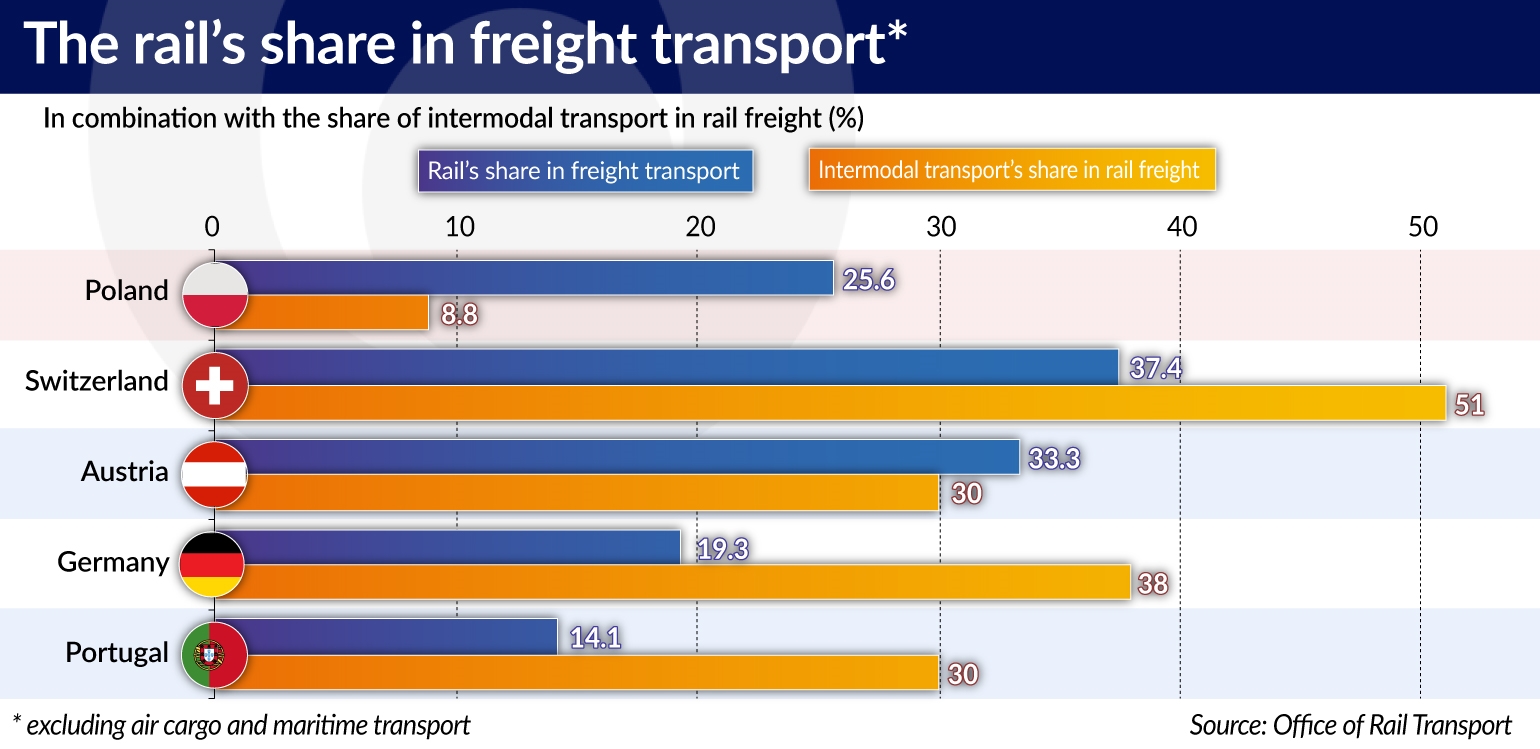

The result is that in many countries rail transport has been gradually losing its share in the transport market. Even Germany, which is one of the most pro-ecological and railway-friendly countries in the world, has not been able to avoid this trend. The share of rail transport in the overall transport of goods initially decreased, then remained at the same level over the past decade (18–19 per cent), and only recently began to rise slightly. Poland still looks very good in this respect, because it is among the European Union’s leaders in terms of the rail’s share in freight transport (this mode of transportation has a 25.6 per cent share in Poland). We need to keep in mind, however, that in 2005 this share reached 37 per cent, and, unfortunately, continues to decline, while the share of car transportation continues to grow. It’s also worth noting that in the years 1990-2015 the railways in Poland experienced a period of collapse: rail transport decreased by almost 40 per cent during this period.

Fortunately, passenger rail transport is starting to bounce back and regain its share of the market. In Western countries and in China, this has largely been the result of high-speed rail, which easily beats cars when it comes to time, comfort and safety of travel.

According to Eurostat data, the number of passengers riding trains has been growing throughout the entire European Union for the past several years. In China and Japan passenger rail transport is very successful, and its share in the overall passenger transport market exceeds 20-30 per cent. For the time being, the EU countries, where the rail’s share is still below 10 per cent, can only dream of such an outcome. However, this is now starting to change in many member states, including Poland, where one can observe a genuine renaissance of passenger rail travel.

On the one hand, Polish cities — following the example of Japan — are experiencing a rapid development of commuter rail. The residents of a city’s peripheries and surrounding areas use it to get to work or schools located in the city center. Such rail is already in operation, among others, in Warsaw, Poznań, the Tri-City (Gdańsk, Gdynia and Sopot) and Łódź, and is currently being implemented in cities such as Rzeszów and Szczecin. The significant increases in the number of passengers of Polish suburban railways confirm the popularity of this solution. The Warsaw Fast City Rail (Szybka Kolej Miejska, SKM), which connects the capital with neighboring towns, carried 3.6 million passengers in 2006, the first year of its operation, and by 2017 the number or passengers increased to 23.1 million.

This is due to several reasons. The first is the phenomenon of suburbanization, in which the inhabitants of large cities move to the suburban areas. The second reason is the sharp increase in the number of cars on the roads and the resulting traffic congestion, as well as the shortage of parking spaces. The residents of many towns adjacent to a large city and the inhabitants of its peripheries can get to the city (and especially to its center) faster by rail than by car. By train, it is possible to get from the outskirts of Warsaw to downtown in 15 minutes, which is much faster than by car.

It is also important that in Poland both the railway companies and the local government units are investing a lot in order to improve the offer of the commuter railways: they are modernizing the tracks, platforms, stations, building new interchange centers next to them, buying new and more comfortable trains (with air conditioning as a standard), increasing the number of connections, and building new stations, for example, near newly developed housing estates.

The number of passengers on long-distance trains is also growing pretty quickly, which is visible in the statistics of PKP Intercity, state-owned, the largest carrier operating on such routes. The number of its passengers increased by 11 per cent in 2017 alone. This results from a significant improvement in the offer, including better trains and connections, as well as the successive modernization of the railway stations, but also from the growing traffic congestion on the roads.

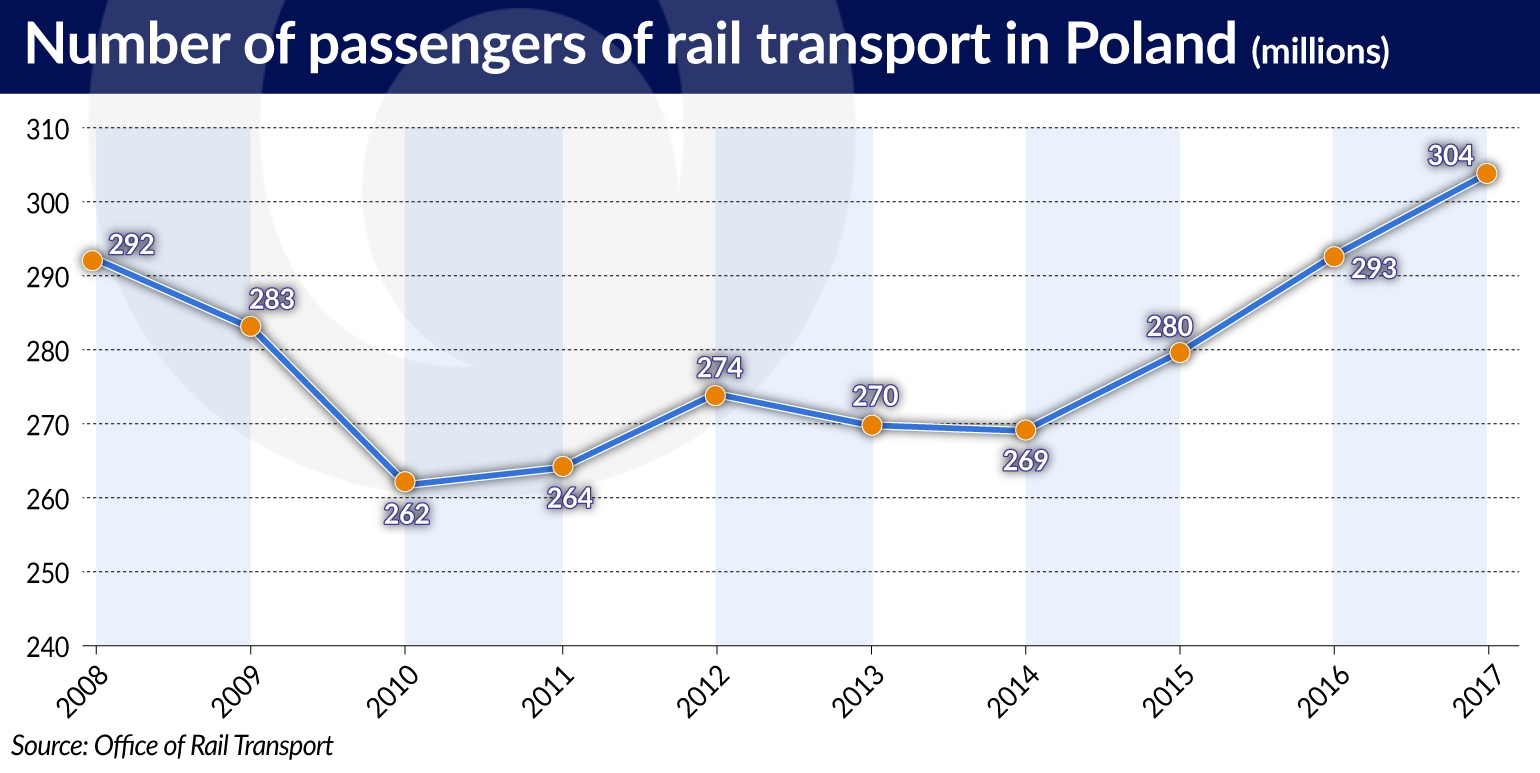

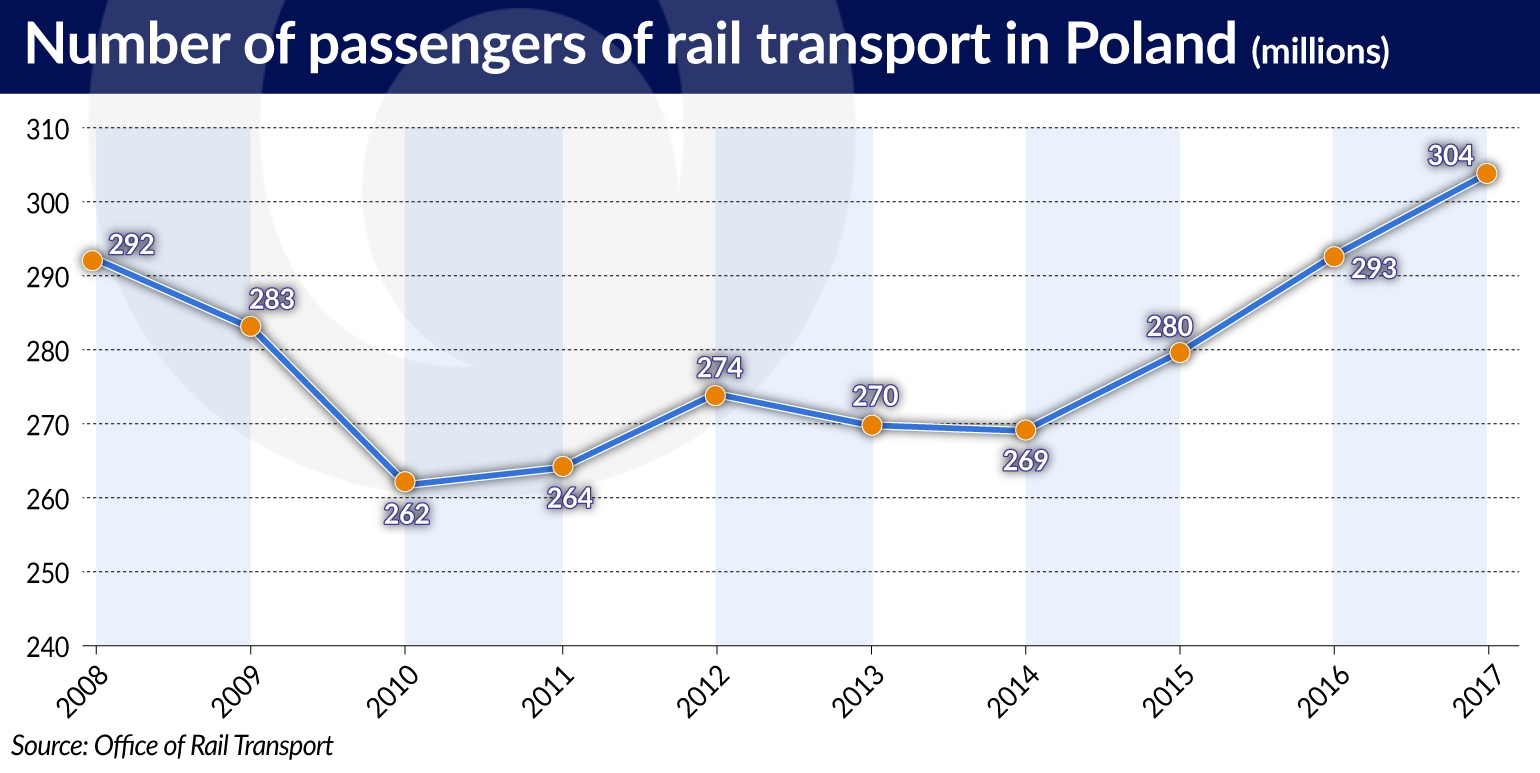

The situation was as follows: the number of railway passengers in Poland had been falling until 2010, but since 2011 it has been growing all the time. However, the rate of these increases still isn’t particularly impressive. Over the last seven years this number has grown by less than 20 per cent (from 262 million to 304 million). The huge modernization program, that has been carried out on the Polish rail for the past several years, has certainly had a big impact in this regard (it will ultimately consume tens of billions of PLN). Unfortunately, because of the implemented investments, many trains are forced to take detour routes and are often heavily delayed. However, when this investment program is completed, the Polish railways will be offering an entirely new quality of service: thousands of kilometers of modern railway lines, hundreds of modernized railway stations and dozens of new, more comfortable trains.

The development of passenger rail in Poland should accelerate as a result. This will not happen automatically, though. A lot depends, for example, on the rates that carriers have to pay for the use of the railway tracks. These rates are very high in Poland, higher than in many other European countries.

The exorbitant rates are one of the main reasons why the freight rail industry is still struggling in Poland. The volume of goods transported on the railways in Poland has been fluctuating and practically hasn’t grown for more than a dozen years. In 2017, this volume amounted to 240 million tons, which was the same as in 2009, but much less than in the years 2004–2008, when it reached 280–290 million tons per year. In the subsequent years, it remained at a much lower level of 220–250 million tons per year.

One important reason for that is also the slow speed of freight trains in Poland, and their serious delays. Once the condition of the infrastructure improves, there will still be the issue of the high track access charges. The model adopted in Poland assumes that the costs of maintaining the railway infrastructure should be covered by the carriers using it and paying for it. This is a healthy model. The problem, however, is that incentives and assistance are needed in order to convince more carriers to transport goods by rail instead of the roads. For example, in Poland many of the rail sidings allowing trains to directly reach the production plants were closed down after 1989.

It would therefore be useful, as suggested by the experts, for the government to launch a program including incentives to re-open these sidings and to create new ones. Such a program has already been operating in Germany for 14 years. It would also be good to introduce incentives for the development of intermodal rail transport based on containers. In the world of transport there is a global trend known as containerization. It means that more and more goods are transported in containers. Standardized containers greatly facilitate transport. They accelerate transshipment, because entire containers are being moved from ships onto trucks or trains, without the need to reload their contents. The same applies for the reloading of containers from trains to trucks. Container transport accounts for the vast majority of the so-called intermodal rail transport, which also includes the carriage of entire trucks and semitrailers aboard railroad flatcars.

Containerization greatly reduces the costs, time and inconvenience of transporting goods by rail. That is why it is such a great opportunity for the railways. It is already being used by many European countries. In the countries in which the share of intermodal transport is already high, the volume of goods transported by rail and the rail’s share in the overall transport market are rising, or at the very least aren’t falling. This is the case, for example, in Austria, Portugal and Germany. Switzerland, which boasts the highest percentage of goods transported by rail in Europe (37.4 per cent), also happens to have the highest share of “intermodal” transport in rail freight, reaching up to 51 per cent. In Germany, this share amounts to 38 per cent, while in both Austria and Portugal it is 30 per cent, and in Poland it only reaches 8.8 per cent.

While a small “intermodal relief” has been introduced in Poland (a discount on the track access charges for intermodal transport), it is definitely not enough to convince more carriers — who are accustomed to transporting goods with trucks and who own large fleets of vehicles — to also use trains. At least these are the conclusions of a report prepared on this subject by the Office of Rail Transport.

Poland lacks systemic solutions such as state subsidies for the construction of intermodal terminals and transshipment facilities, which are applied in Germany. In Switzerland, all freight trains have impressive discounts (40 per cent) on the track access charges, and much lower electricity charges are applied for night trains. This is a good deal for power plants, because electricity consumption drops sharply at night, so they welcome any way to increase it during that period and to ensure more stable electricity production. The Swiss also charge drivers for the so-called costs of congestion, i.e. increased traffic on the roads, by adding them to the road use charges included in the prices of fuel. This is supposed to provide a level playing field for rail and road transport.

Of course, this costs a lot, but it also pays off. Especially when we consider the costs of being stuck in traffic and the effects of the increased air pollution or the noise generated by cars.

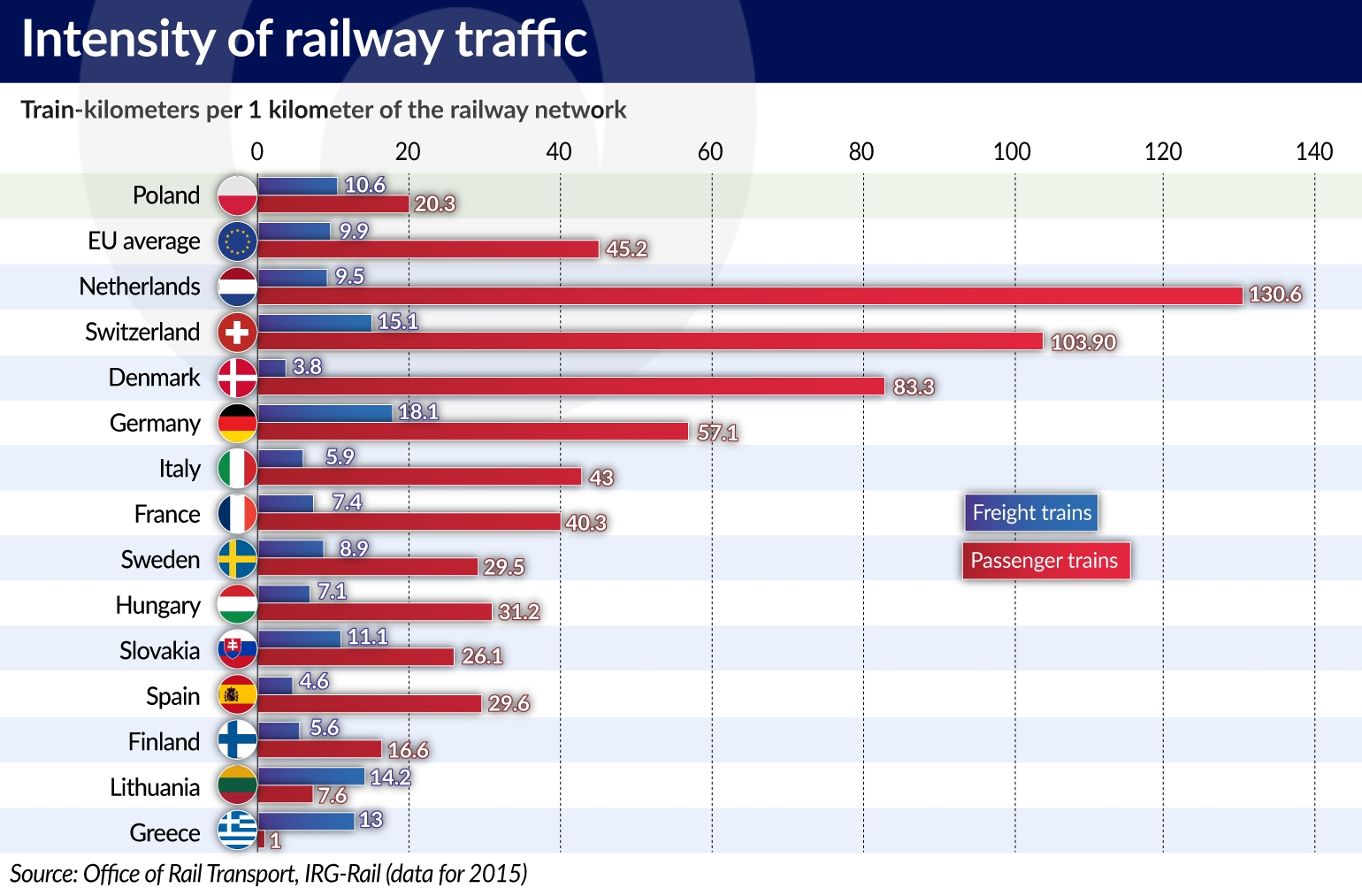

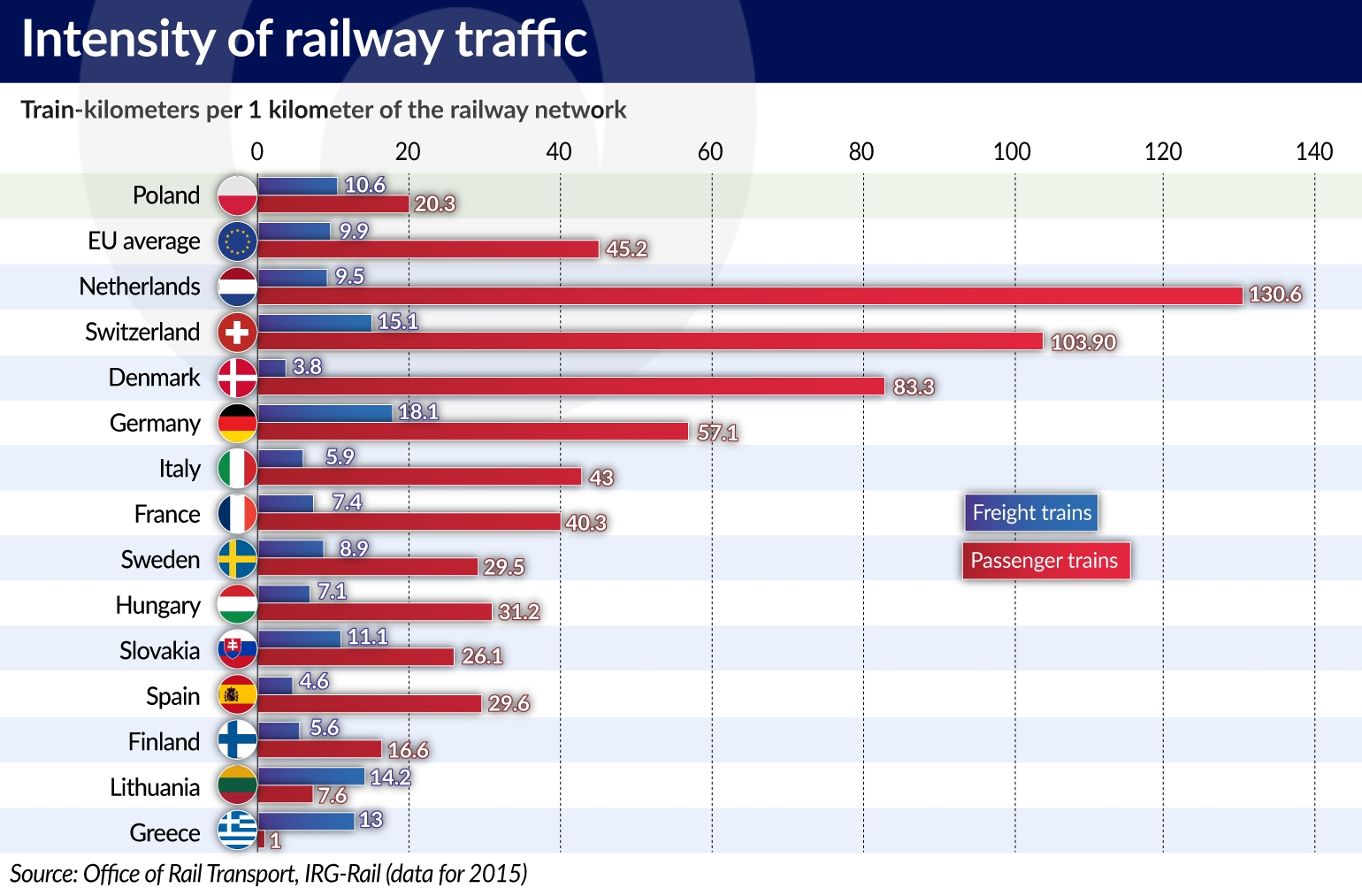

Finally, it should be mentioned that for the time being the Polish railways only utilize a small percentage of their carriage capacities. This is clearly visible in statistics illustrating the intensity of rail traffic in the individual European countries.

In Poland this intensity is several times lower than in countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark and Germany. In this respect Poland also does worse than Italy, France, Sweden, Spain, Hungary and Slovakia. This shows that the Polish railways have the potential to relieve the roads to a much greater extent than they do at present.