Russia is too small to win the war in Ukraine

Category: Macroeconomics

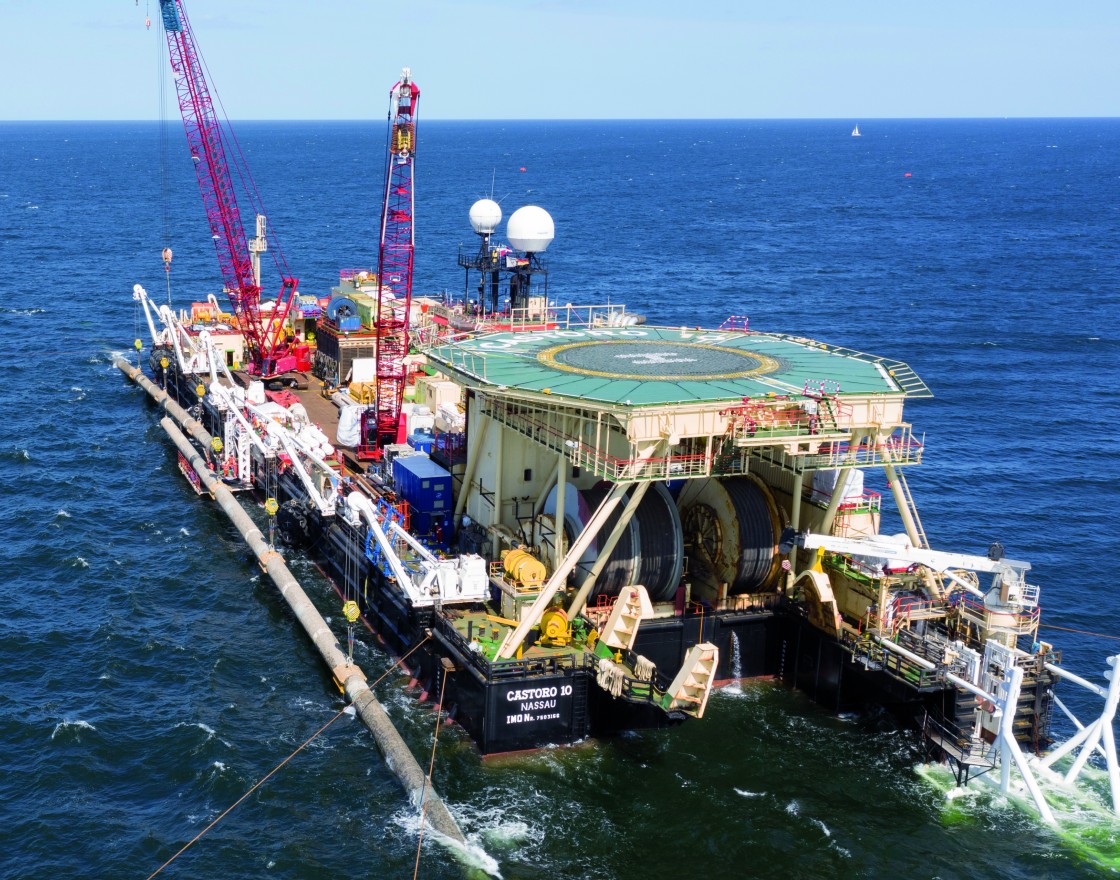

Bay of Greifswald, Germany (©Nord Stream 2/Axel Schmidt)

The disapproval adds to pressure from the US and its Central European ally Poland to scrap the controversial project. “The Polish government and PGNiG (Poland’s state-owned gas company) have been consistently vocal about risks combined with the Nord Stream 2 project,” Polish oil and gas company PGNiG said in a statement. “The pipeline strengthens the dominant position of the major supplier of gas to the EU and to its neighbors like Ukraine or Belarus. It does not provide diversification of sources of gas and as such is not in accordance with the goals of EU Energy Union. Given the overcapacity of existing transport routes for Russian gas to the EU, the project does not respond to market demand, but provides additional leverage for potential market abuses by the dominant supplier. In 2016, eight EU leaders in an official letter objected to the construction of Nord Stream 2 pointing to the principle of energy solidarity and energy security. The investor also disregarded the applicability of EU law to the pipeline. Completion of the pipeline in spite of its non-compliance with EU policy, opposition from several Member States as well as investor efforts to not apply the EU law would mean the prevail of brute force over EU principles,” said PGNiG.

The 1,230-kilometer (775-mile) pipeline is set to run from Russia’s Ust-Luga, but is on hold 160 kilometers off the German coast, after US sanctions came into force before Christmas. The EUR10bn project would double Russia’s direct export capacity to Germany as a first entry point to the EU to 110 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year. With its last nuclear plant shutting down in 2023, coal in terminal decline and the phasing out of Dutch gas, Germany faces a medium-term challenge of how to secure stable energy sources and manage the vicissitudes of solar and wind plants. Some 69 per cent of the gas consumed in the EU is imported (and two-thirds of that from Russia) and that is set to increase to 86 per cent in 2050. So what options are available as Berlin seeks to navigate these choppy waters?

The German Green party has called on Ms. Merkel to use the project to press the Kremlin into answering allegations over poisoning of Alexei Navalny, Russian opposition politician. In the polls the party is currently second to the CDU and a likely contender for the next coalition government. Meanwhile, Norbert Röttgen, chairman of the Bundestag’s committee on foreign affairs and a candidate for the CDU leadership, said completing the project would amount to encouraging Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “inhuman and contemptuous politics.” Süddeutsche Zeitung wrote: “The government waved goodbye to a fiction. A fiction that made it possible to slap Russia with sanctions one day and court it as a business partner the next.”

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is reportedly working on developing sanctions similar with the ones used by the US. This would please the US, which has criticized European countries for their reliance on energy from Russia. Washington is currently threatening to impose its own sanctions on companies involved in the pipeline.

Critics of sanctions point to an avalanche of litigation from companies involved in NS2 and its onshore connecting pipelines because many legally binding contacts would be violated. “In turn this would result in massive damages, running into billions of euros to be paid,” Katja Yafimava, of Oxford University, says.

Ms. Yafimava believes that in addition, it would also have a negative impact on how Russia sees doing business in the EU. “This is when even a project such as NS2 — which has been done strictly in line with the laws applicable at the time and without the slightest legal, commercial or environmental irregularity — could be hijacked by a political matter with no relevance for the project,” Ms. Yafimava says.

She believes Russia would likely re-assess not only its economic but also political relationship with the EU and with Germany. “For these reasons I think it would not be a big exaggeration to compare any possible attempt by Germany and/or the EU to pause/cancel NS2 as an attempt to make the Iron Curtain 2.0,” she adds.

“Every EU member state would have to prepare for being a US target at some point. Today, the focus is on NS2, but tomorrow it could be on computers, ships, cars or something else,” said Daniel Caspary, head of the German conservatives group in the European Parliament. „We have to resist from the beginning.”

Officials in the Economics Ministry in Berlin believe the US has gone after NS2 so aggressively primarily because it wants to sell its own gas to Europe.

Decouple Mr. Navalny from commercial narrative has a certain attraction. “It would be Merkel’s answer to the Americans and the despised Trump Administration for all the ignominies, real and imagined, she has suffered,” Ariel Cohen, Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, said.

Merkel’s spokesman Steffen Seibert, asked if Merkel still insisted on decoupling the Navalny’s case from the NS2 project, said: „The chancellor believes that it’s wrong to rule anything out.”

“Germany has for long insisted on the project being strictly commercial and that there should be a distinction between the commercial and the political,” Anna Mikulska of Rice University said.

Ms. Milkulska notes that Germany, and Western Europe as a whole, was a major partner to the Soviet Union when it came to gas purchases during and despite the Cold War. “Hence, there is a precedent to following up on commercial ventures despite strong political rifts and disagreement on the issue with the US,” she says. “Also, Germany has been counting on Russian gas as it transitions its energy system away from coal. As opposed to for example Poland, Germany has not been as keen to build large LNG import terminals to offset Russian gas, rather it ‘leaned in’ a large supply of cheap gas,” Mikulska adds.

Brenda Shaffer, an expert on Russia at Georgetown University, said the pipeline is needed for three main reasons. „One, it means cleaner energy for Germany. Berlin talks the talk, but doesn’t walk the walk on emissions. Without more gas in its energy mix, Germany will remain over-dependent on coal, especially after the next round of closure of nuclear plants. Secondly, for Germany the relationship with Russia is extremely important and gas trade is seen as a positive component in their cooperation. And thirdly, transiting gas all the way down to Ukraine and back up to Germany is set to become way more expensive after Russia starts producing in the Arctic north,” she said.

The Navalny’s case might actually give Berlin commercial advantage in its relations with Gazprom. “The idea would be that as a large demand center Germany will have a good bargaining position over Russia, potentially even influence,” Ms. Mikulska says.

Meanwhile, in Sassnitz, the rumor has been going around that construction has continued in secret. Since May, the Akademik Cherskiy — a Russian ship that replaced the Swiss vessels — has been in port.

The German government had long hoped that the construction of an LNG terminal in Brunsbüttel outside of Hamburg would be enough to assuage the US. “Both the plans for our LNG terminal and the plans for Nord Stream 2 have been pursued in parallel for years,” said Katja Freitag, Public Affairs and Regulation Spokesperson at German LNG Terminal GmbH. “We are convinced that an LNG terminal will support the diversification of supply countries, as well as supply routes with a view to avoid one-sided dependencies in energy supply. This would result in more competition in the German gas market which will benefit both business and consumers. It will also help maintaining the attractiveness of Germany’s business environment by providing an efficient, cheap, and reliable energy supply which is a key part of every business decision. Besides feeding into the German natural gas grid, the development of an LNG bunkering infrastructure and the associated positive impact on air quality and therefore quality of life for many people are other relevant aspects associated with an import terminal,” she continued.

But, the two sources can be complementary. “The more diversification the better,” Kirsten Westphal, senior associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, said. „An LNG Terminal in Germany is interesting, but not a necessity as Germany is well connected to other LNG terminals and thus flexibility in the integrated north western European market is high,” she said. US LNG to Germany could be delivered today via the huge LNG facility in Rotterdam, currently utilized at a level of 25-30 per cent and connected with the German network.

Furthermore, some countries in Central and Southeast Europe (CSE) could have even better secure supplies through Germany, Ms. Shaffer believes. „Forcing Ukraine off its dependence on Russia energy transit fees is also not a bad thing and it is good to get Russian entities out of a major role in the Ukrainian economy,” she says.

This is heavily contested. Benjamin Schmitt, a former European Energy Security Advisor at the US Department of State, argues that NS2 is not being developed to bring significant new gas volumes to Germany and Western Europe, but rather to harm the economic and strategic security of Ukraine by providing an alternative conduit for Gazprom to sell its gas to European markets. He says only 9.9 bcma of the 55 bcma NS2 pipeline’s capacity is actually allocated for delivery to Germany and the west, with the remainder set to exit Germany en route to the Czech Republic and ultimately the gas hub in Austria — the current de facto end point of the Ukrainian gas transit route. „The linkage of US LNG sales with the US opposition to NS2 is not grounded in technical, political, or market reality,” Mr. Schmitt said. „Rather this faux linkage has been advanced across Kremlin disinformation platforms and by some NS2 supporters in Europe in order to set forth a false choice,” he says.

“The US opposition to the Kremlin-backed project has been strongly bipartisan starting with the Obama administration where the project was opposed in public statements by an array of senior officials including Vice President Joe Biden, who called NS2 ‘a bad deal for Europe,’” Mr. Schmitt added.

Meanwhile, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, the successor to Merkel as head of the CDU, said in late 2018 that one option to the politicization of NS2 could be to reduce the quantity of gas flowing through it.

There is an option that in the near future the NS2 pipeline won’t be used for natural gas at all, instead becoming instrumental in the production of hydrogen. “NS2 pipelines would be technically capable of transporting hydrogen — so this is a possibility and could be helpful to decarbonize the EU energy system,” says Ms. Yafimava.

In order to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, European industrial companies will have to radically change production strategies and transition away from fossil fuels and toward hydrogen in the coming years. But until enough environmentally sustainable hydrogen is available, the gap could be plugged by hydrogen manufactured via the chemical transformation of natural gas, a process called steam-methane reforming. In the case of NS2, that transformation could take place at source — in Russia. The thus released CO2 could conceivably be pumped back into the ground in the Russian gas fields and the hydrogen could then be sent to Europe via the pipeline. Benefits for the climate could be enough to unite Europeans and weaken the US position.

“As to the hydrogen option, I am skeptical about it,” said Mr. Kubiak. “A hydrogen-switch is currently not an option for Nord Stream 2 and it still won’t become the one for a many years. Any plans to blend hydrogen into the gas pumped through NS2 will have to be properly studied and will require addressing lots of absolutely crucial issues first. Where and how the hydrogen would be produced in Russia? How will it be transported through the Russia and will that be economically feasible at all? Will the consumers in Europe need hydrogen blended into the Russian gas? How German infrastructure should be adapted to actually handle Russian hydrogen-natural gas blend transmission?” Mr. Kubiak added.

The fudge seems to be the most likely option. Delay or water down German sanctions against Russia, but use them as a bargaining chip to improve market position for German gas buyers, wait for an investigation into the Mr. Navalny’s case and hope that public opinion shifts, and — perhaps — that a Trump defeat in November will allow for a fundamental recalibration of German-US relations.

“Rejecting NS2 would be a political decision with a heavy commercial and policy impact and therefore we see Merkel speaking harshly against the attack against Navalny but not necessarily moving quickly to impose any restrictions. The bottom line is that Merkel is likely to fudge. She would placate the US by moving along on some LNG purchases; temporarily suspend, but not terminate, NS2, and force Putin to commit to the Ukraine gas transit,” Mr. Cohen says.

Mr. Seibert added at the press conference that Berlin was „certainly not talking months or the end of the year in waiting for a reply from Moscow.”

Meanwhile, as Ms. Mikulska points out, Gazprom is also involved in antitrust proceedings initiated in 2018 by Poland’s Office of Competition and Consumer Protection (UOKiK) against all companies involved in NS2 financing, while Germany’s Bundesnetz (Federal Network Agency) has once rejected NS2’s application to be exempted from a key EU directive. „These are formidable issues likely to delay the pipeline and make it more expensive,” Ms. Mikulska said. “A lot will depend on Navalny’s outcome: if he fully recovers, Germany may want to turn the page over. If he is left incapacitated, it will be more difficult to do,” Mr. Cohen concludes.