Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

The coal mining sector in Poland is mainly controlled by the State. Besides coal mines associated in the Polish Mining Group (Polska Grupa Górnicza), Katowice Coal Holding (Katowicki Holding Węglowy) and Jastrzębie Coal Company (Jastrzębska Spółka Węglowa) there are also Lublin Coal Bogdanka (Lubelski Węgiel Bogdanka) of Enea group and Tauron Mining (Tauron Wydobycie) of Tauron Group.

Private entities dealing with coal production include PG Silesia, belonging to Czech EPH (the biggest private coal entity on Polish market), and Siltech and Eko-Plus coal mines – jointly generating less than 3 per cent of coal output in Poland.

Each of the mines act pursuant to the mining concession issued by the Ministry of Environment. In addition, the Australian company, Prairie Mining, has a valid mining concession still not exercised, obtained after the acquisition of the inactive Dębieńsko mine (by purchasing the plant, the company also acquired the concession).

Investors willing to build mines in Poland have no mining concessions for the time being (none of them have submitted the relevant application yet); however, they have concessions for exploration. Those concessions allow them to explore potential deposits (mainly by means of deep earth drilling), assess them and subsequently potentially decide on applying or not for the mining concession.

Potential investors include the aforementioned Prairie Mining company which, besides Dębieńsko, intends to build the Jan Karski coal mine near Lublin in the neighborhood of Bogdanka, with which it has a pending court dispute concerning coal deposits. The next investor interested in Polish coal is the German company HMS Bergbau which wants to construct a coal mine in Orzesze; however, it would like to use part of the infrastructure of a Krupiński coal mine belonging to Jastrzębie Mining Company. This coal mine should terminate excavation in 2017; but so far no agreement has been reached between HMS, JSW and the State Treasury concerning the utilization of some of its equipment.

Kopex, the manufacturer of mining machines, also intended to build its own coal mine near Oświęcim. Its financial situation is very difficult and it may be soon taken over by a competitor.

The largest number of projects in Poland, four in total, were created by the Australian company Balamara. Two projects in Jaworzno would be associated with the reactivation of the inactive Jan Kanty and Siersza coal mines but the authorities and inhabitants of Jaworzno are not very happy about it. The third project is located in the Lublin region (also close to Bogdanka) and the fourth one is in Nowa Ruda in Lower Silesia, i.e. in the inactive Wałbrzych coalfield. Coking coal from the latter could be supplied to the Victoria coking plant, sold by JSW to TF Silesia and the state agency ARP. It’s located 40 km away and produces approx. 400,000 tons of foundry coke per year (for its production, approx. 560,000 tons of coking coal are needed).

“There is no reason why Polish coal should not continue to play a significant role which may increase Polish GDP. We have capital and the know-how,” states Michael Hale, a director in Balamara Resources.

In his opinion, new mines with significantly lower production costs offer the opportunity for Poland which may become a significant coal supplier in European markets in the coming years.

Both Beata Szydło, the Prime Minister, and Krzysztof Tchórzewski, the Minister of Energy, have recently spoken about the need to build new modern coal mines. Did they also mean investment by private investors?

The last Polish coal mine built ‘from the scratch’ is Budryk in Ornontowice, opened in the 1990s. Obviously the existing coal mines have developed since then; however, all those factors affected costs – mining activity is moving into deeper and deeper levels. The average depth of deposits in Poland is 850 meters, and complicated excavation and increasingly difficult conditions translate into costs (the problems include expenditure on air conditioning, risk prevention and transport of coal to the surface).

If it is assumed that some currently operating coal mines will be closed, which seems unavoidable in view of the necessary restructuring of the sector, it may turn out within several years that there will be a coal deficit. Although today, when a surplus of approximately 10 million tons of steam coal per year is recorded, the import of 10 million tons of fuel (necessary for coking plants as the production of coking coal, the basis for steel production, is insufficient in Poland) certainly sounds a little strange.

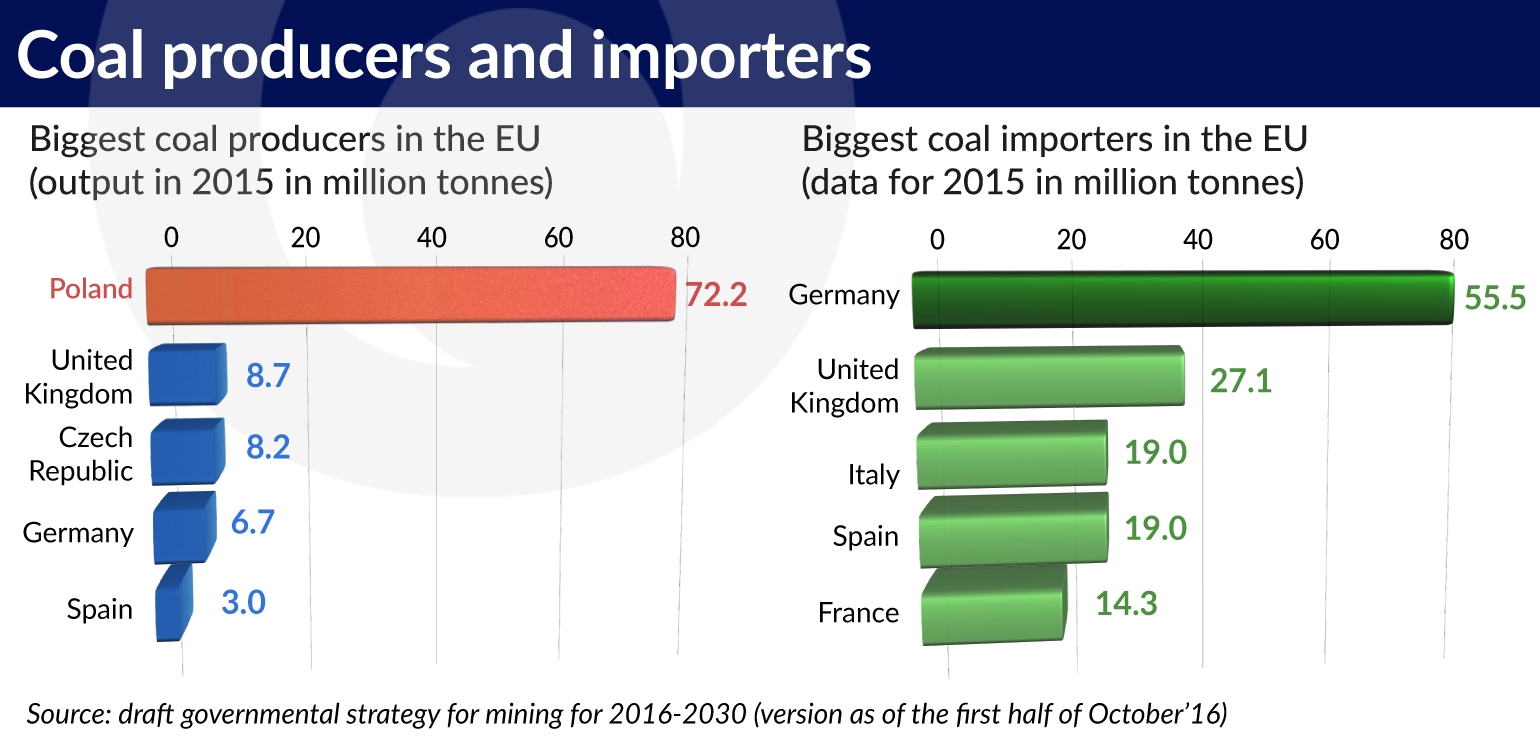

However, some investors willing to build coal mines in Poland do not think of the domestic market at all but rather of the EU market. Nowadays, coal import to the EU amounts to approx. 180 million tons per year. For the sake of comparison, Poland produces approx. 70 million tons. The power and heat generation sectors need approx. 55 million tons, individual consumers – approx. 11 million tons, and coking plants – approx. 12.5 million tons.

Private investors declare the intention to build new plants in Poland and to employ more than 10,000 people and supply approx. 22 million tons of hard coal per year.

Everything will depend on whether and when they will receive the concessions. The Polish state, as the owner of the majority of the Polish coal mines, is interested mainly in remedying the part of sector that it controls. PGG, established in May after the acquisition of Kompania Węglowa coal mines, has PLN2.4bn of the total capital injection guaranteed. JSW sold a part of its assets with a total value of over PLN700m; it also received a capital injection for the extension of the coal processing plant (over PLN200m), and it is still planning to issue bonds for PLN300m. On the other hand, KHW needs approx. PLN1bn to avoid bankruptcy.

All this is a part of the Poland’s government plan to save coal mines. For the time being, those companies can forget about building new plants, although several years ago Kompania Węglowa had such plans in the Lublin region.

The state does not need private competition to show that it is possible to operate better and cheaper.

The new strategy for the hard coal mining sector for 2016-2030 is supposed to be ready by the end of the year. It may bring some hope for change. In its draft one can read that the concession process shall be simplified and accelerated; however, no details have been presented so far.

“The geological and mining law contains provisions related to the investor’s financial capacity; however, the Ministry of Environment, which awards concessions, has neither competence nor knowledge to check such an investor. Today both MPs and ministers imagine that an investor willing to build a coal mine has PLN2bn on its account at the start. Obviously, financing is built in stages, besides, not all costs are paid at once,” explains an interviewed representative of one of the companies intending to build a mine in Poland.

The fact that state-owned mines often wait for decisions for a similarly long period is a questionable consolation. Recently one of PGG’s coal mines whose concession was close to expiry received a new concession just a few days before the expiry of the old one.