(CC BY freefotouk/DG)

A point of reference for the analysis of the Warsaw summit should be “Trends in global CO2 emission – 2013 report” published in October by the European Commission and PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the report:

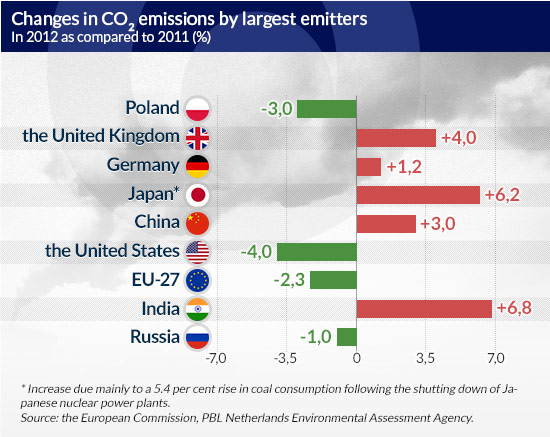

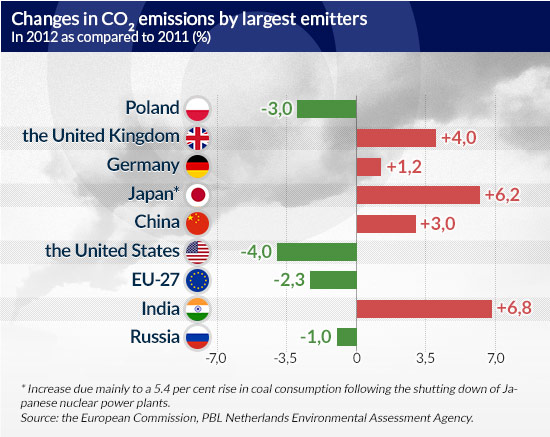

Firstly, 2012 was the year of coal renaissance in many countries; coal is the main „culprit” of excessively high global carbon emissions, accounting for 40 per cent of their total volume. It is still being used, as it remains the cheapest source of energy and our part of the world, adversely affected by the crisis, is looking for savings. Paradoxically, the greatest coal consumption increase has been recorded in the EU, even though Europe is the world leader in the fight against global warming. In the UK and Spain, coal consumption increased last year by as much as 24 per cent; in France, which boasts a large share of nuclear-generated electricity, the use of coal rose by 20 per cent and in Germany by 4 per cent.

In Poland, coal consumption fell by 4 per cent and in the Czech Republic by 8 per cent. Despite the renaissance of this material in some countries, its global consumption in 2012 increased only by 0.6 per cent, while the consumption of crude oil rose by 0.9 per cent and of gas by 2.2 per cent. In the U.S., coal is mainly replaced by gas, but in many other countries it is being ousted from the market mainly by renewable energy sources. The share of renewables in global energy production in the last six years has doubled, reaching 2.4 per cent. Among other reasons, it was due to the decisions made in China, the world leader in wind energy (one fourth of the world’s windmills are located in China); the country has also been breaking world records in the domain of hydropower. China’s hydropower production capacity increased in 2012 by 24 per cent, leading to a 1.5 per cent drop in the country’s CO2 emissions.

Therefore, contrary to what is often being said in Poland, not only the European Union has been fixated on renewable energy sources.

infographics: Darek Gąszczyk/CC BY-NC-SA by jimhflickr

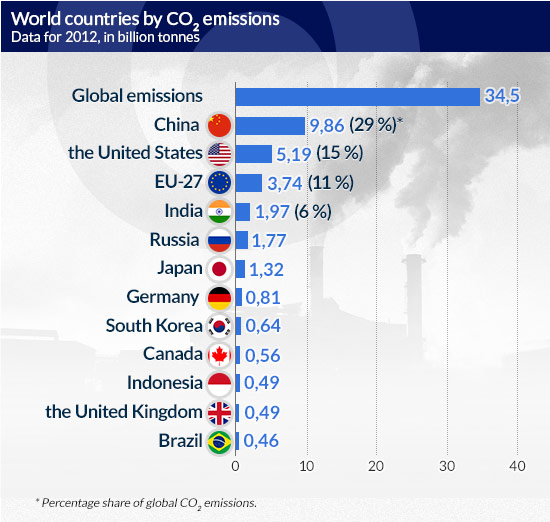

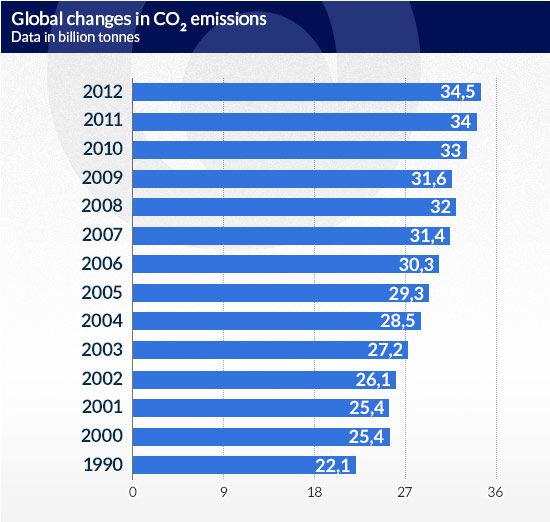

Secondly, carbon dioxide emissions throughout the world are closely related to the economic situation. In 2009, as a result of the crisis in the developed world, emissions decreased by 1 per cent for the first time in years. A year later, when the world entered a phase of slight economic recovery, they increased by as much as 4.5 per cent. In 2011, when the global economy slowed down again, CO2 emissions increased by only 3 per cent, and in 2012 only by 1.1 per cent. However, economic downturns are not always an ally in the fight against climate change, as many affected countries approach the fight with less enthusiasm than before and are less likely to invest in green technologies. The United States are a good example: in 2010, the country was about to launch its own CO2 emissions trading system, but in the face of the financial crisis, its implementation was postponed.

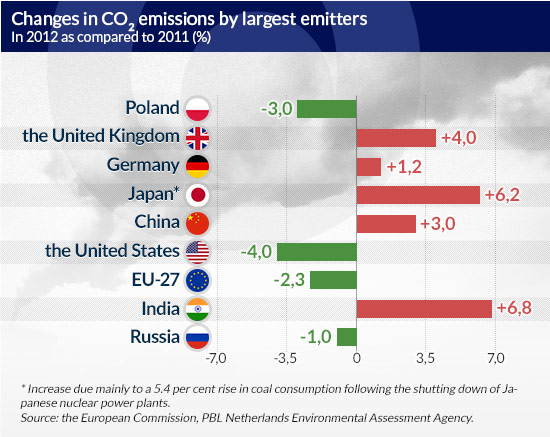

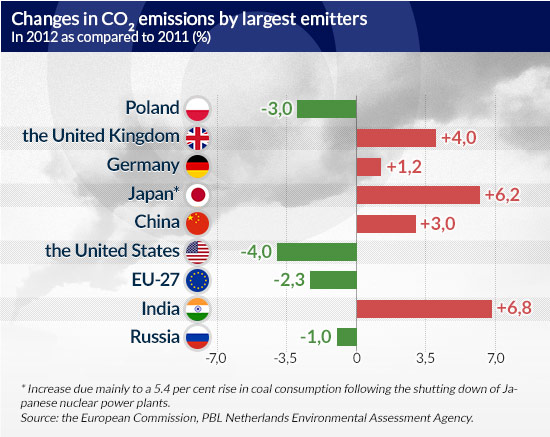

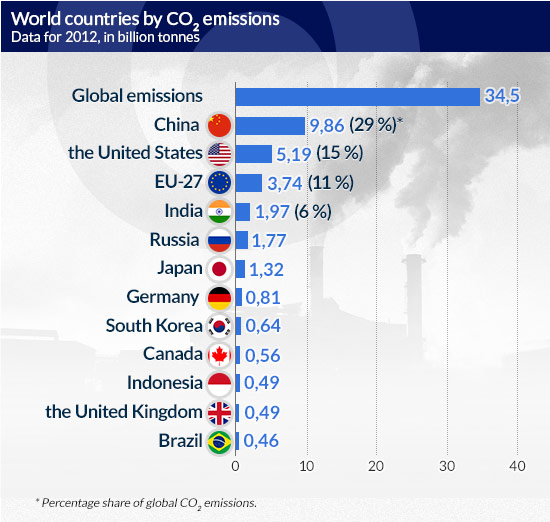

Thirdly, global economic growth in 2012 reached the level of 3.5 per cent and carbon dioxide emissions increased over that period by as little as 1.1 per cent. In other words, the world can develop its economy without increasing CO2 emissions. This is largely due to the approach of the countries that are the biggest carbon emitters in the world: the United States, China, India, Russia, Japan, Brazil, Germany, South Korea, United Kingdom and Indonesia. In the U.S., carbon dioxide emissions decreased for two consecutive years, in 2011 and 2012, by as much as 4 per cent, while GDP grew over that period by 2 per cent. Carbon emissions also fell in the UK and Russia (by about 1 per cent). In Indonesia, they remained at the same level. In the remaining countries from the above list, the increase was moderate.

infographics: Darek Gąszczyk/CC BY-SA by olmed0

The world is growing with less energy

How to account for that? The world’s demand for energy is growing quite rapidly, mainly due to developing countries, and this leads to raising energy prices. This trend is likely to continue in the years, or even decades to come. For this reason, developing countries have agreed to reduce their consumption of raw materials (and the less they consume, the less greenhouse gases are produced) through the introduction of energy-saving technologies.

Many countries have recognized that the development of new technologies of energy generation and consumption is an opportunity for economic development, as it has the potential of creating thousands of new jobs and entirely new industries. It was one of the reasons for Germany’s decision to invest in renewable and energy-efficient solutions. Consequently, the country’s renewable energy sector employ 380 thousand people – more than the coal sector. China follows on the heels of the Germans, as it is today the largest global manufacturer of wind turbines and photovoltaic devices for the generation of electricity from solar energy. They would not have achieved this had they had begun to implement themselves these new technologies on a large scale. China is not the only developing country to boast such successes. India started to implement a pilot energy certification system, designed to encourage the reduction of energy consumption already back in 2008. Two years later, it introduced a similar system for renewable energy.

infographics: Darek Gąszczyk

What to expect in the years to come

According to the report, the process of inhibiting the growth of global CO2 emissions may be maintained in the next few years. For this to happen, a number of conditions must, however, be fulfilled:

First, China must follow through on its plan to reduce its economy’s energy intensity by 2015 and to increase the share of gas in its energy production to 10 per cent by 2020.

Second, the United States must continue the shift away from coal and towards gas and renewable energy.

Third, the EU must fix its CO2 emissions trading system to ensure its effectiveness. This means that it should be able to encourage companies to invest in the so-called low-carbon technologies. It is very likely that all of these conditions will be met.

Given the above, why organize another climate summit if the world is increasingly committed to energy efficiency and renewable energy and, consequently, to reducing greenhouse gas emissions?

The problem is that all that is being done is still not enough. According to climatologists, curbing emissions is not sufficient to prevent excessive global warming (temperature rise by more than 2 degrees Celsius). In their opinion, emissions should be further reduced. Paradoxically, the process may be impeded by both a global economic downturn and an economic recovery.

Germany, for example, as a consequence of shutting down nuclear power plants, increased its carbon dioxide emissions last year, , and this again increased the share of coal in energy production. There are concerns that China and the United States – for economic reasons – cannot reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as much as they promise. They risk nothing for not meeting their commitments.

A new agreement is needed

In other words, without a new global agreement whereby individual countries undertake – under the threat of sanctions – to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by a specific quantity, the latter may continue to grow.

The first global agreement of this kind (although not introducing any financial sanctions) was the Kyoto Protocol, which entered into force in 2005. It was ratified by the majority of the world’s countries, and its adoption was determined by Russia’s accession. It required the more developed, richer countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 2012. The reduction level was different for each country countries. In the case of the EU-15, it was 8 per cent (as compared to 1990), while Poland’s target was 6 per cent. Poland’s benchmark, however, was not 1990, but 1988, due to the fact that the country was at the time in the process of profound economic transformation.

The Kyoto Protocol was a flawed agreement because it was not ratified by the United States – the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world until the beginning of the twenty-first century (it was taken over by China in the middle of the last decade). Although the U.S. declared that they intended to restrict their emissions, they did not want to have their hands tied by any commitments, or to yield to international control. However, the Kyoto Protocol and its implementation can be considered a success. The majority of countries that ratified it have reduced their greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with the commitments made. The results achieved by of some of them were significantly better than initially planned. Poland, where CO2 emissions were reduced by as much as 30 per cent, is one of the top record-breakers in this respect.

The Kyoto Protocol expired in 2012 and participants of the subsequent climate summits have wondered what to do next. It is increasingly suggested that not only developed, but also developing countries should make commitments to reduce CO2 emissions, as they have become the largest, next to the United States, Russia, Japan and the EU, „producers” of carbon dioxide in recent years.

At last year’s COP 18 summit in Doha, it was decided to extend the Kyoto Protocol until 2020. The countries which have ratified the 2013-2020 protocol are to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by a specific value. This commitment, however, did not include a number of large emitters, such as China and India. What is more, for the time being only the European Union has decided to ratify this document (it committed to a reduction which had already been adopted in the EU’s climate and energy package, namely 20 per cent by 2020), along with Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, Ukraine, Australia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Monaco and Liechtenstein. Together, these countries account for as little as 14 per cent of global CO2 emissions.

The United States do not intend to ratify the extended Kyoto Protocol: they claim that their decision is based on the conviction that not only developed countries, but also other major emitters, in particular China, India and Brazil should commit to reducing emissions. The latter are, however, reluctant to do so. China explains that developing countries should not be treated in the same way as developed countries that initiated the process of global warming. However, it is willing to commit to reducing CO2 emissions after 2020. This solution seems acceptable also to Brazil and several other major „producers” of carbon dioxide from the group of developing countries. At the summit in Durban two years ago, it was established that by 2015, a new global climate agreement would be worked out and implemented five years later, in 2020.

I’ll do it if they do it

This new agreement is a major subject of debate at the climate summit in Warsaw. Will it lay the foundations for a „new Kyoto”? It can prove difficult. The United States still refuse to commit to any specific targets. Developing countries are demanding money from developed countries to finance climate policies and commitments to a greater than before reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. These are unrealistic demands.

The European Union intends to play first fiddle, as it has assumed the role of the world leader in the fight against global warming. When working out the EU’s position at the Warsaw summit, as many as 20 EU countries and the European Commission wanted the Community to commit to increasing the reduction of CO2 emissions to 30 per cent by 2020 (today, it is 20 per cent). It was to „give an example” and encourage other countries to make certain commitments for the period between 2013 and 2020. Poland strongly objected to it, and for this reason the new target was not included in the EU position.

Nevertheless, proponents of a stricter EU climate policy do not give up their fight. They intend to advocate the raising of the 2020 reduction target at the level of the EU. They also champion the so-called backloading (aimed at increasing the price of CO2 emission allowances in the EU emissions trading system). Their aim is also to ensure that documents requiring the EU countries to reduce CO2 emissions by as much as 40 per cent in the period 2020-2030 are adopted as soon as possible.

This is done despite the strong counter-arguments form the opponents of such solutions. The most important one is that the current EU climate policy is ineffective. It will remain so as long as similar commitments to reducing greenhouse gas emissions are not accepted by other big emitters, such as the United States. The EU accounts for only 11 per cent of global C02 emissions. If it committed to reducing the emissions by 20 per cent by 2020, it would mean reducing the amount of carbon dioxide emissions by just over 2 per cent on a global scale.

Attention to side effects

Some claim that such a policy would, paradoxically, lead to an increase in global emissions, for instance because the EU’s climate policy would result in an increase in energy prices in the EU, which in turn would lead to the relocation of European plants to countries where electricity and heat are less expensive. The distance that would have to be covered to transport goods to the European market would be greater, though, which means additional CO2 emissions. What is more, production plants would operate in countries that do not take any measures to counter global warming.

Offshoring the production from the EU to these countries would even encourage the latter to perpetuate irresponsible attitudes that ensure their greater competitiveness. It is not only the case of Asian or African countries. Currently, the average price of electricity in the EU is 37 per cent higher than in the U.S. and about 20 per cent higher than in Japan. According to data from EnergSys, energy price index for EU industry has increased over the last seven years by 38 per cent, while In the United States it fell by 4 per cent during this period.

– If nothing changes, in 10-15 years time electricity prices in Europe may be twice as high as in the U.S., and several times higher than in China – said Buzek. – In eight years, the EU is to import two-thirds of its energy, while the U.S. seeks to reduce energy imports.

Non-European countries approach reducing emissions in a more pragmatic manner than the EU. The goals that they impose on themselves are not as ambitious as those of the EU. In the U.S., for example, several states have adopted their own regional systems of carbon trading – ETS, or an emission trading scheme. One of them is California – economically the most powerful American state. Kazakhstan has introduced its own national ETS this year, along with New Zealand. Australia, South Korea and China are all preparing for the implementation of a similar solution.

China will soon launch a pilot system of CO2 emissions trading to be implemented regionally; in 2015, it intends to create a national ETS. This solution, based on a market mechanism, is considered to be one of the best ways to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere – even if it is still failing in the EU and has come under a lot of criticism. The European Union has been the first to introduce it, as it strives desperately to protect its position of the global climate trendsetter and leader. This may be, however, come at a high price.