(E. Strathmeyer, CC BY-NC-ND)

“The global financial crisis followed by the euro area crisis led to steeper growth declines in CSE than elsewhere. Real GDP growth in CSE dropped to an average of 1.9 per cent over 2011-15 from an average of 6.1 per cent over 2002-08, showing a much sharper decline than in other emerging or advanced economies,” the IMF observes in its report “How to Get Back on the Fast Track”.

This was not just a cyclical effect. Potential growth itself dropped to 2 per cent, which is about half the pre-crisis figure. The most likely causes indicated by the IMF are lower productivity growth and the slower pace of capital accumulation.

There is no improvement in sight. On the contrary ¬¬— demographics are unfavourable, global growth is poor (and we may even be in permanent secular stagnation) and capital is going to be more and more difficult to come by. There is no alternative but to boost potential growth by means of difficult structural reforms.

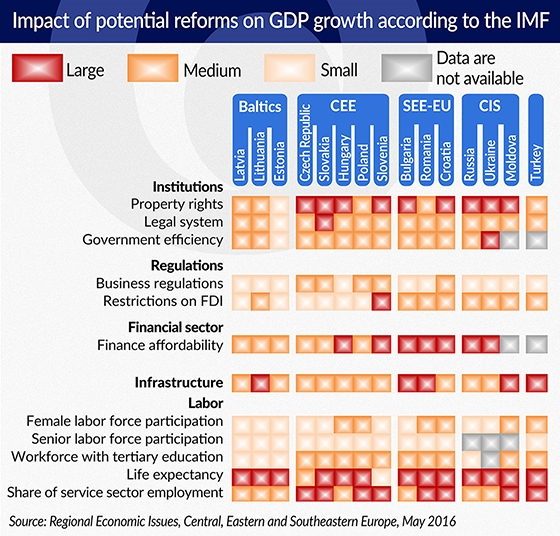

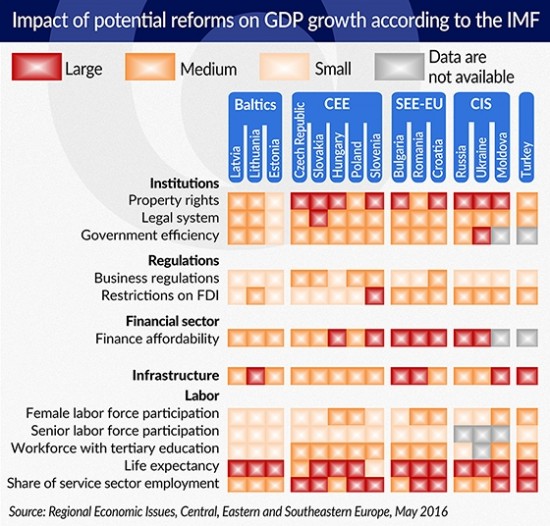

The IMF repeats this sentence in each edition of its regional report. This time, however, it is accompanied by some hard facts. They are presented in an inconspicuous table estimating the impact of specific reforms on growth in specific countries. The adopted benchmark is the EU-15.

(Inforgraphics Bogusław Rzepczak)

And so in Poland, only two reforms of the 12 listed would have a strong impact on GDP growth: increasing life expectancy and increasing the share of the service sector in the economy. The reforms with the lowest impact would be lowering barriers to FDI (apparently, it is not too bad already) and improving senior labor force participation (which is surprising).

In contrast, Ukraine had as many as 4 red fields, i.e. areas where improvement would boost growth the most: life expectancy, property rights, government efficiency and finance affordability. The last factor would also considerably benefit Russia, Hungary, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia.

A relatively simple reform consisting in investment in infrastructure would still be highly beneficial to Lithuania, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova and Turkey.

The countries which need to improve their protection of property rights are Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Bulgaria, Croatia, Slovenia and — surprisingly — the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In the latter, the entire legal system is marked in red, so it needs reforming in the first place.

The IMF points out that generally capital stock per capita in a typical CSE economy is merely a third of that in developed European countries.

“The countries should focus on institutional reforms that reduce inefficiencies and increase returns on private investment and savings. In most of the region, domestic savings rates are lower than those required to sustain investment rates high enough to close the income gaps with advanced Europe within a generation or so,” IMF writes.

IMF assumes that the domestic savings rate equivalent to at least 25 per cent of GDP is a prerequisite for rapid convergence. Only six countries are above this line: Belarus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Slovenia and Russia. Slovakia is just below it, Romania and Poland are slightly lower.

The table on emigration is interesting too. As it turns out, as many as 20 million people have left CSE countries over the past 25 years, accounting for 6.5 per cent of the working-age population.

“Analysis suggests that in 2012, cumulative real GDP growth could have been 7 percentage points higher on average in CSE in the absence of migration during 1995-2012. As a result, on average, CSE members of the EU could have narrowed their per capita income gap with the EU average by an additional 2 percentage points. Emigration may have also created pressures on social security systems and hindered growth through increased growth-unfriendly labor taxes,” the report states.

The relevant chart shows that if it had not been for emigration, the per capita GDP in relation to the overall EU average could have been as much as 5 percentage points higher in Croatia and about 3 percentage points higher in Estonia and Slovenia. Interestingly enough, Poland (along with Lithuania and Hungary) is a country which lost the least on emigration — just over 1 percentage point of GDP.

The report is available on the IMF website.