Why Has Japan’s Cash Demand Remain Strong?

Category: Macroeconomics

Economist, works at NBP, specialises in monetary policy issues and FX markets

ECB headquarters, Frankfurt, Germany (Paul!!!, CC BY-ND)

The ECB, however, sees no alternative but to increase the dose of the monetary antibiotic, i.e. cut interest rates even further and increase bond purchases. But its chances of success are rather slim.

On March 10th the ECB decided to launch yet another interest rate cut and expand the quantitative easing program. All these measures are intended to encourage banks to step up their lending even more vigorously in the hope that this will help invigorate the economy and, as a consequence, boost inflation.

The ECB manages its toolbox in such a way that it is even prepared to pay commercial banks a bonus for deigning to take out loans at the central bank, thanks to which they will be able to boost lending to the real economy. What I am referring to is a modified version of the program known as the TLTRO (Targeted Longer-term Refinancing Operations). Its new edition (TLTRO2) is designed in such a way that every bank which decides to borrow from the central bank will be charged negative interest by the same central bank.

In other words, it is not the bank that will have to pay the central bank for money it borrowed, but the central bank will pay the commercial bank for accepting money from it. For this to actually happen, the bank will have to demonstrate at least a 2.5 per cent rise in lending by the end of January 2018. Then the bank in question will be “charged” a fee equivalent to the current deposit rate. As the rate is negative, this means the ECB is the one who will pay a bonus. If such a high threshold cannot be achieved, the bonus paid by the central bank will be lower.

The idea seems revolutionary but it is not. For almost four years now, the ECB has been discouraging banks from keeping money in deposit or current accounts at the central bank. Since June 2014 it has even collected a fee in such cases. Yet excess liquidity in the sector keeps expanding and has reached a level last recorded in 2012. Why? Regrettably, despite the incentives offered by the ECB and even the willingness of banks to lend, clients will not take loans. This is not surprising amid the anaemic economic environment in Europe and the slowdown in China.

The ECB is therefore in a predicament. Since it has decided on an unconventional therapy, it is hard to back out now. The effects though, in terms of increased lending and stimulating inflation, look faint. As far as the latter is concerned, any possible effects are hampered by the slump in the prices of oil and other commodities in annual terms. Hence, during the last press conference, President Mario Draghi asked the participants to consider where inflation in the euro area would be if it had not been for the measures taken by the ECB.

Rather than being drawn into these hypothetical deliberations, journalists’ attention turned to another fragment of his statement indicating that the ECB was not prepared to reduce the rates ad infinitum. It was unequivocally assessed as a sign that the ECB was aware of how dangerous therapy it was resorting to. And the therapy may indeed involve numerous side effects.

The first one could be a deterioration in the financial condition of commercial banks. There must be some justification for the reports about the financial difficulties experienced by the biggest banks of the euro area. What is the use of the really attractive incentives the central bank offers, if banks keep over EUR800bn in current accounts and deposit accounts? If the minimum reserve is deducted from this amount (approx. EUR113bn), then on the annual basis (at a rate of minus 0.4 per cent), we obtain a cost of approximately EUR2.8bn for merely parking these funds at the central bank.

In 2015, according to Barclays’ analysts, German banks accounted for over 34 per cent of the entire surplus cash held by banks in the central bank. It is no wonder then that some Bavarian savings associations were even considering opening a joint vault to minimize the losses. Of course, even an amount as high as EUR3bn should not incapacitate banks. The macroeconomic consequences of the therapy, such as a real estate bubble, could be far worse. The point is that people, intimidated by the extremely low interest rate, will prefer to invest in the stock market or the above-mentioned real estate one.

However, the party the most hurt by the ECB therapy will not be the German banking system but the average German petty saver. The Handelsblatt daily, quoting Union Investment, claims that over the next 5 years German households may lose up to EUR224bn. It is also interesting to look at the calculations of Olaf Stolz, a German Professor of the Frankfurt School of Finance, illustrating how much an average German will have to contribute to banks as a consequence of the ECB “therapy”. In 2007, a 35-year-old had to put away approx. EUR168 for the retirement pension. The amount ensuring the same retirement pension has already gone up to EUR360 today. Simultaneously, despite deflation, the currency lost over 11 per cent of its purchasing power over the same period.

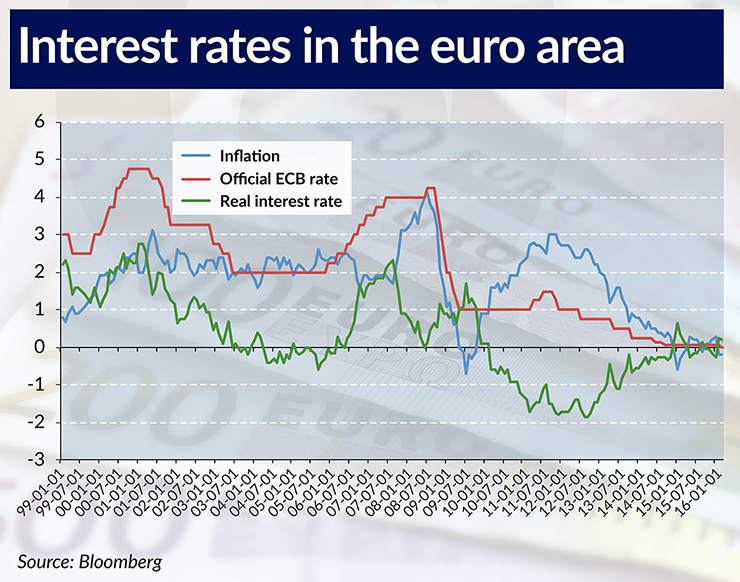

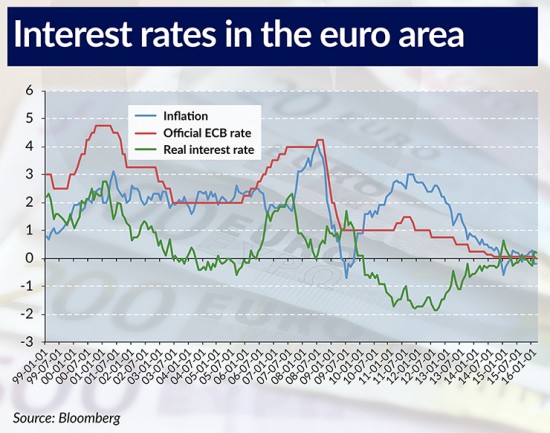

(Infographics: Bogusław Rzepczak)

And this is not all. Germans love cash, as the Deutsche Bundesbank reports in its analytical study. In an attempt to shun the impact of negative interest rates, Germans are likely to become even more fond of cash and accumulate their savings in cash. Unfortunately, the ECB and the German government want to make it more difficult for them to use cash. The ECB wants to withdraw notes of the largest denomination (i.e. the EUR500 banknote), and the German government intends to limit cash payments to the amount of EUR5,000. No wonder there is talk of a violation of fundamental civil liberties in Germany.

The proponents of the restrictions are (supposedly) guided by the desire to curb access to unrestricted cash payments to terrorists and the grey economy. It is a weak argument though, since terrorists, for example, are fee to use the even bigger Swiss denominations. The newly introduced restrictions are rather a sign of the desire to pave the way ¬— by means of an official decree — for negative interest rates into the wallets of ordinary citizens. To an average German it makes no difference who initiated the limitations on cash payments. What counts is that these limitations make it even more difficult to escape from banks, which can at any time impose a negative interest rate on the money deposited by citizens.

The ECB is therefore in an awkward situation, aggravated by old animosities. The President of the Bundesbank, Dr Jens Weidmann, has clearly not forgotten the bitter pill that Draghi administered him in September 2012, when the ECB President disclosed who was the only one of the then 17 presidents of the central banks to have voted against the program to rescue the euro area from the debt crisis. Despite the truce with the ECB, Weidmann firmly supported the preservation of the EUR500 note, winning great applause among his fellow citizens, who are so strongly attached to cash.

The ECB has helped overcome the debt crisis in Europe. At least such was the assessment of the vast majority of the observers. Nevertheless, there is a risk that such a favourable opinion about the ECB can still be revised. By a strange coincidence, nearly all the countries hit by the debt crisis in 2010-2012 (recently joined by Ireland) and as a consequence subjected to the remedial program are now in a deep political crisis. It is the ECB that is increasingly often blamed for the political stalemate. The continuation or even the deepening of the negative interest rates policy can only help this kind of narrative to spread.

The situation appears to be getting out of the ECB’s control. Feeling obliged by its mandate, it rightly focuses on combating the too low inflation rate. The last time inflation in the Eurozone was close to the target but still below 2 per cent was in February 2013. Such a long period of departure from the target inflation level set by the ECB has not been seen since the establishment of the ECB.

However, by concentrating too much on treating one illness, the ECB seems to pay no heed to other dangerous symptoms afflicting the European economy and society. A central bank without a vision for the future bodes ill for a euro area troubled by the spreading political crisis and the wave of refugees pouring into the continent.