However, there are still many new threats to growth, which also applies to Polish banks, despite operating on what continues to be considered the most attractive market in the region.

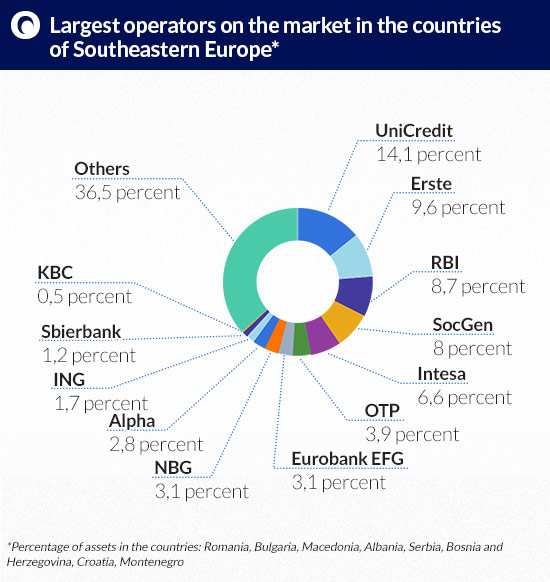

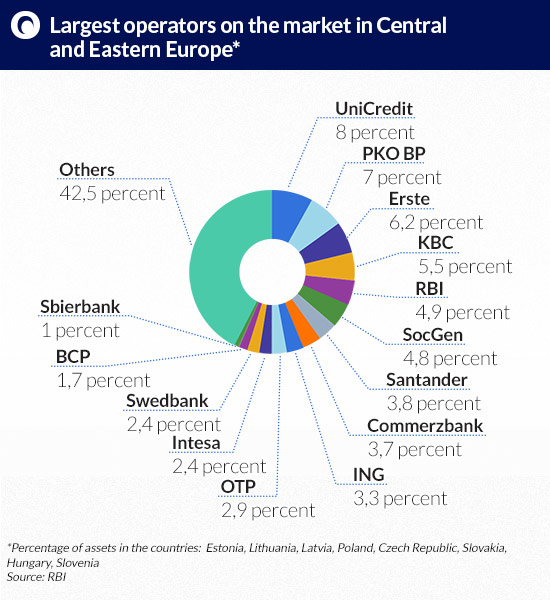

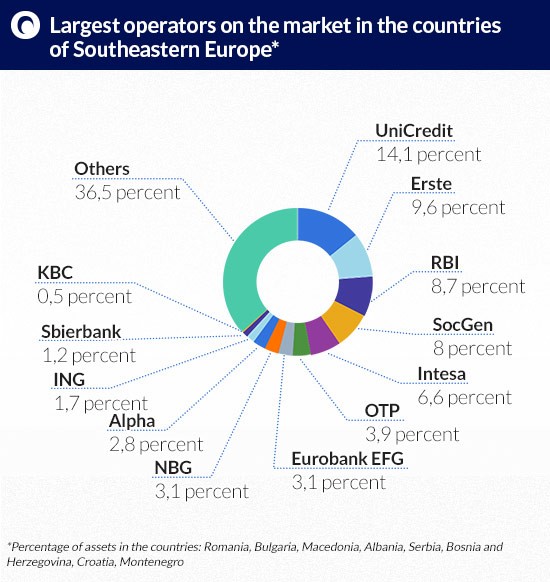

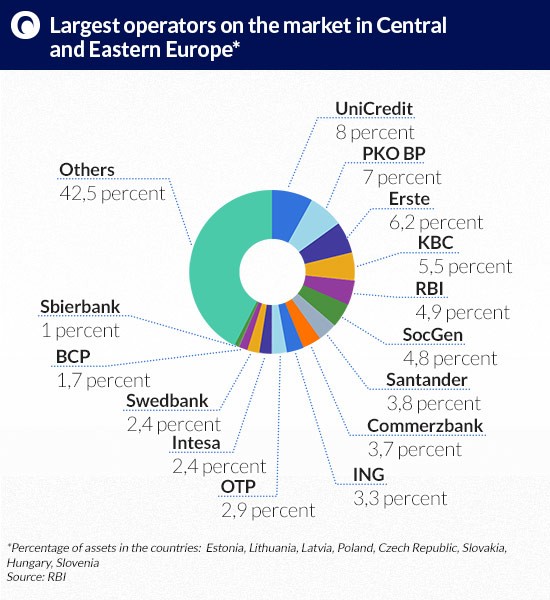

The structure of the banking sectors in countries across Central and Eastern Europe and Southern Europe appears to be similar. Most bank assets are owned by large cross-border banking groups primarily from the countries of the euro zone. Those with the strongest presence in the region include Austria’s Raiffeisen and Erste, Italy’s UniCredit and Intesa Sanpaolo and France’s Societe Generale. The situation of the major players and their strategies will determine the future of the banking sectors in the entire region.

Differing structures

In Poland, the situation is different in that the country also hosts European groups that are not – or only marginally – represented in other countries: Santander (BZ WBK), Commerzbank (mBank) and ING (ING BŚK) each hold a 4 per cent to 5 per cent market share. Greek banks have significant market shares in the south of the region and Sweden’s Swedbank dominates the banking sectors of the Baltic States.

The pre-crisis policy of strong expansion, the supply of wholesale financing to subsidiary banks, and setting sales targets for them, especially in the mortgage markets, was similar in almost all the countries and almost all the groups. This policy dominated in the entire region, although not all the groups pursued it.

In Poland, UniCredit (Pekao) and ING (ING BŚK) were not keen on issuing Swiss franc loans before the crisis. That will give them an advantage in the new credit cycle that is just beginning.

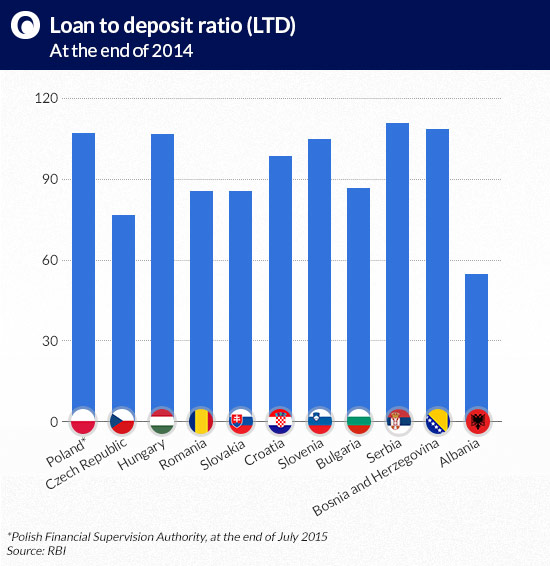

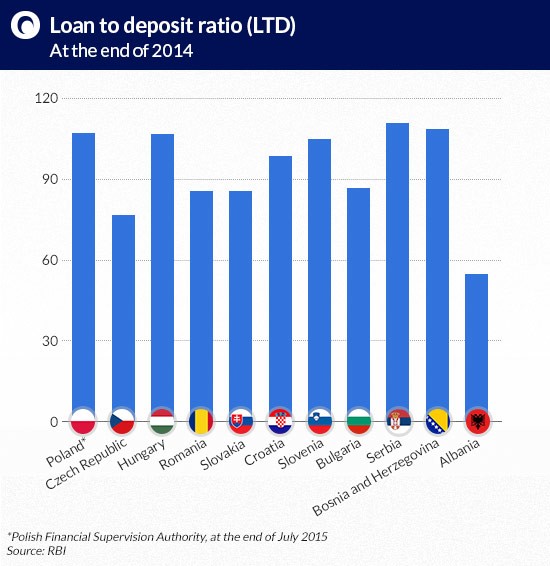

The Czech Republic and Slovakia also avoided foreign currency lending. The two countries are among the few with relatively low loan-to-deposit ratios, providing good prospects for expansion in the new cycle.

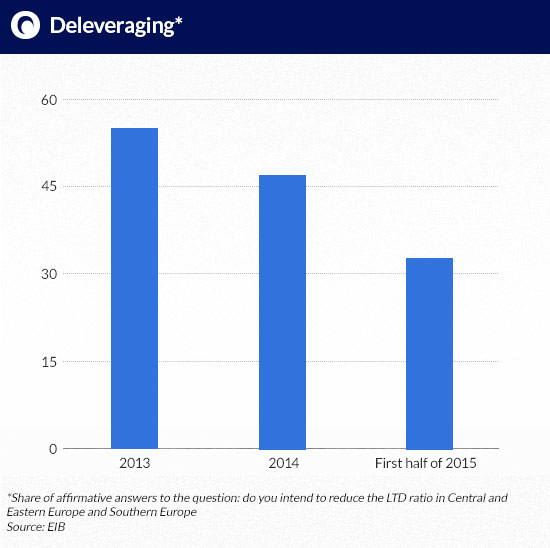

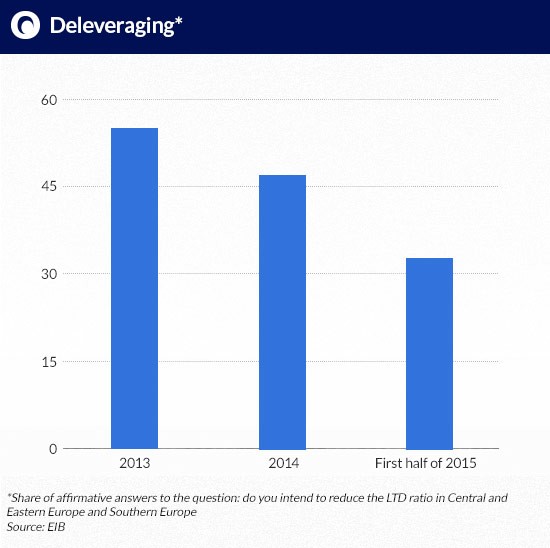

Following the outbreak of the crisis, all the countries in the region went through a process of deleveraging, even though in Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia its extent was much smaller than elsewhere. Deleveraging was not a regional phenomenon. In recent years banking groups have deleveraged in Spain, Portugal and the United Kingdom. In Ireland, the volume of credit in relation to GDP fell by more than half, from over 200 per cent to just above 100 per cent from the end of the credit boom to the end of last year. None of the countries in our region experienced such a drastic change.

Polish market the most competitive

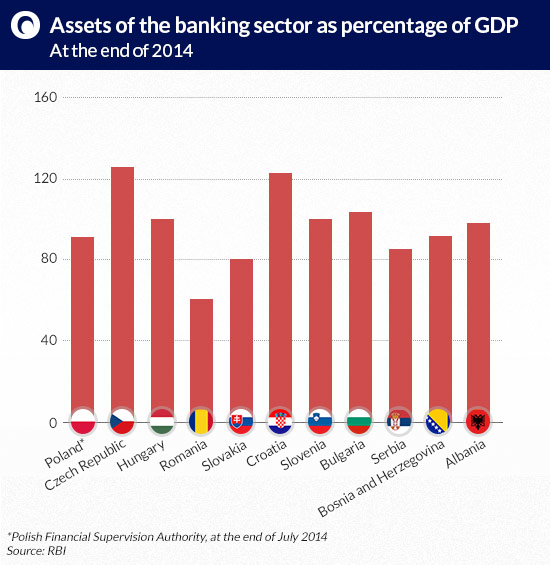

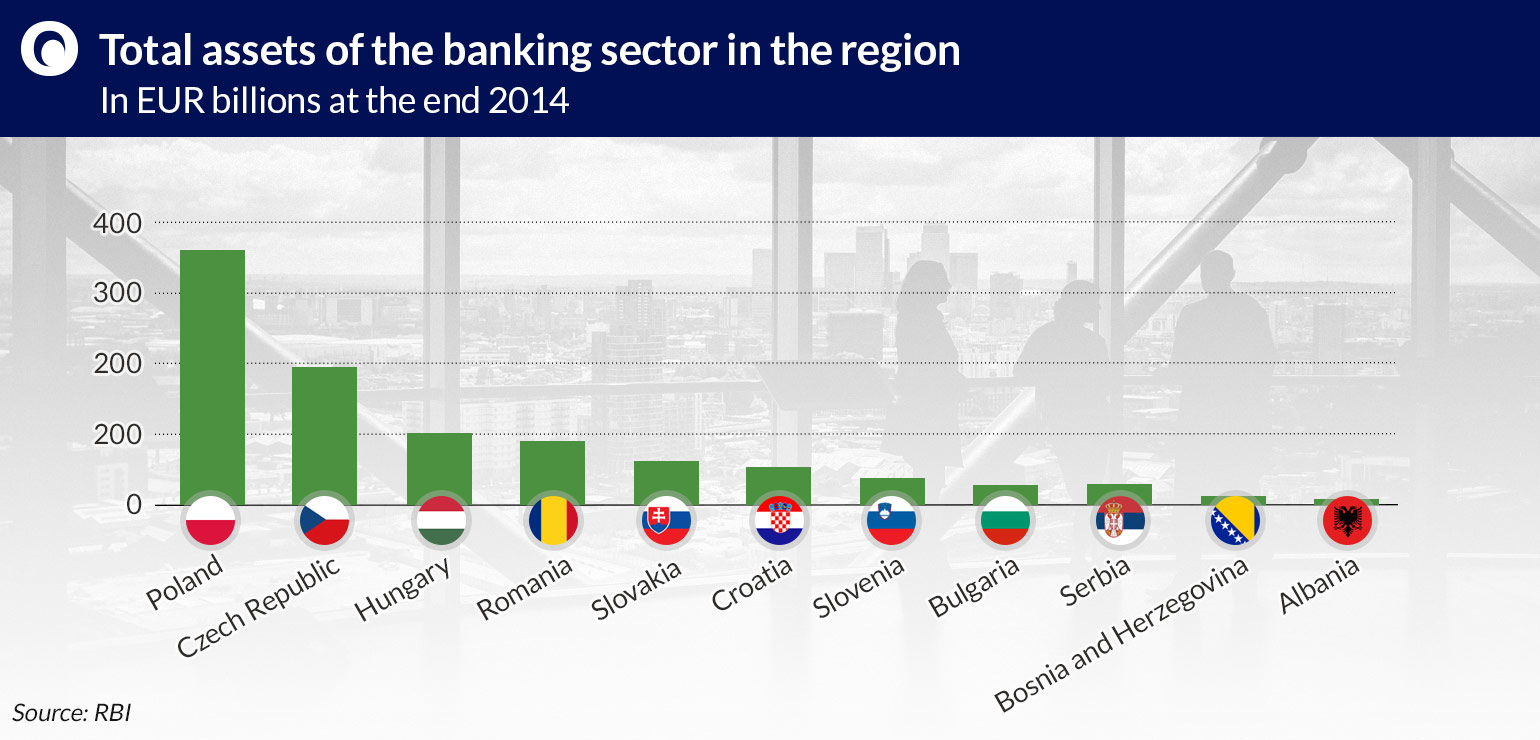

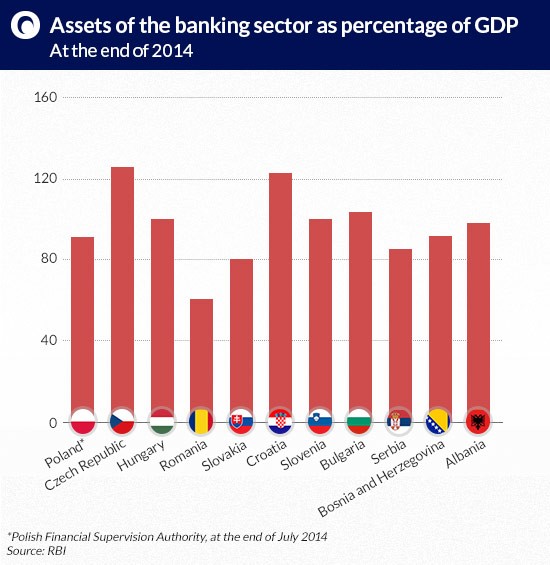

Despite similarities with other countries, also in terms of post-crisis pressures, Polish banks do stand out. The big difference is scale – Poland has largest economy in the region and also the largest banking sector. Polish banks hold assets worth a total of EUR 360 billion, which is the same as the combined value of the Hungarian, Czech and Slovak banks.

The structure of the banking sector is also different. Poland has a large number of banks, many with a relatively small market share. The top five banks combined hold less than a 50 per cent share in the assets, which makes the banking sector highly competitive.

The assets of the three largest banks (PKO, Pekao and BZ WBK) account for a mere 26.8 per cent of assets of the entire sector, while in Hungary the three largest institutions hold a 36.8 per cent share. The concentration is even higher in the Czech Republic, where the assets of the three largest players reach 50 per cent, Croatia, with the three largest banks representing a 57.4 per cent share, or Slovakia – 58.1 per cent. That fragmentation affects the profitability of banks.

The third difference, which has been less significance in recent years but could potentially be important, is that Poland’s largest bank (PKO BP – nearly 16 per cent assets of the sector) is an institution dependent on the state. In all, the state controls 20 per cent of the sector. In the region as a whole, including Russia with its giant share of state-owned banks, the average state-owned share is 15 per cent. The share of foreign investors in the assets of Polish banks is only 60.4 per cent, whereas for example in Croatia it reaches 92 per cent.

…and has the greatest potential

A new study by the European Investment Bank (EIB), covering 15 European banking groups, shows that they perceive the Polish market as one with the highest potential. Two-thirds of the surveyed groups still assess it as high, and the rest see it as average. In this respect Poland is ahead of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Romania, where only 40-50 per cent of the answers assess the market potential as high. The potential of the Polish market received a better assessment than in a similar EIB’ survey conducted six months earlier.

At the same time, two-thirds of the groups saw their position in Poland as satisfactory, although none was happy enough with their positioning to assess it as optimal (the highest mark). One-third, however, believed they have a weak position. It is easy to guess that these are the groups that are strongly represented across the region, but with only 2-3 per cent market share in Poland.

For as many as two-thirds of the groups operating in Poland, the risk-adjusted return on assets is better than the average for their group, and for the others it is comparable. In this respect only the Czech Republic and Slovakia are more „rewarding”, whereas Croatia, followed by Hungary and Albania, are at the bottom.

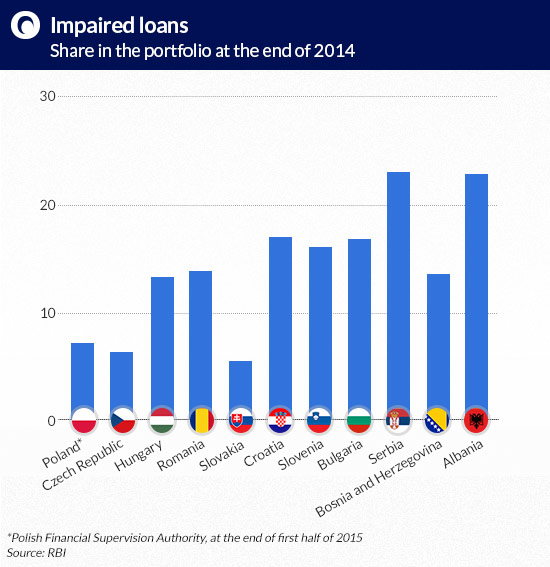

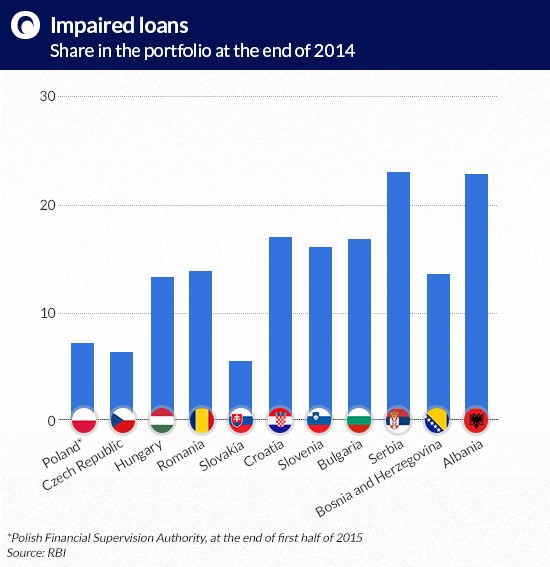

Despite the credit boom of 2005-2008, Polish banks managed to avoid, at least on a scale seen elsewhere, its extreme symptoms, both with respect to corporate and household lending. The fact that economic growth was sustained during and then after the crisis also enabled banks to maintain relatively ‚clean’ portfolios, as ultimately proved by last year’s asset quality review (AQR). At the end of the first quarter, the ratio of non-performing loans (NPL) was 7.1 per cent. In this respect, only Slovak banks (5.4 per cent at the end of 2014) and Czech banks (6.3 per cent) did better.

Swiss franc sure to harm Polish banks

The pre-crisis bubble in mortgage loans denominated in foreign currencies could cause major problems for Polish banks, but the final result should not be as unfavourable as in Hungary. Analysts from Raiffeisen Bank International point out that in contrast to Hungary, the scale of Swiss franc-denominated debt in Poland does not pose such a high systemic risk, and they expect less radical measures.

As a result of the debt crisis and the conversion of loans denominated in Swiss francs into the forint, Hungarian banks recorded a slightly positive ROE in only two of the last five years (0.3-1.1 per cent) and during two consecutive years negative ROE exceeded 10 per cent. In Hungary foreign currency loans accounted for 12 per cent of GDP even after the first conversion in 2011, while in Poland they currently account for 10 per cent.

The situation of borrowers in both countries is different, due to the generally more reasonable and transparent policies of banks in Poland. In 2010, the ratio of bad mortgages in Swiss francs reached 25 per cent in Hungary, while it is currently only 3.3 per cent in Poland.

Swiss franc loans in Hungary tended to have a much higher interest rate, one detached from the LIBOR rate. The rate was variable, but unilaterally determined by the banks, thus forcing clients into a debt spiral. In Poland, the loans carried interest at the LIBOR rate for the Swiss franc plus the bank’s margin, which, given the current negative LIBOR rate, has partially mitigated the franc’s recent appreciation.

Swiss franc-denominated loans portfolios pose the biggest long-term risk to Polish banks. First, the rise of the franc against the PLN could hurt the repayment rate. Second, the awareness of the risk creates pressure for solutions to covert these loans into PLN. This is where the politicians begin to exploit the issue for political gain, without regard for the health of the banking sector.

Loan conversion legislation currently debated in parliament is unlikely to be enacted. Initially, it included fairly conservative proposals, which were then radically altered. Even the more reasonable proposals – splitting the cost of loan conversions equally between banks and customers, and covering only the loans with the highest risk for the banks, i.e. the ones with the highest LTV, would still result in the sector’s losing of more than a dozen billion PLN over the next few years. This is the size of the annual profit of the entire banking sector. If banks were forced to bear these costs, it would lead to a plunge in the profitability of at least some of them. The cost of raising the necessary capital would also change rapidly for some institutions.

Southeastern Europe at turning point

The economic growth recorded last year in nearly all the countries of Southeastern Europe, the purging of bad loans in a number of countries, and the halting or the decline of their growth in others, are all signs indicating that a new credit cycle may be starting, according to RBI forecasts.

Credit demand – including for investment loans – is rising. Profitability has returned to some markets, such as Romania and Hungary, where banks incurred deep losses in recent years. An increasing number of banking groups are turning an operating profit. For 80 per cent of them, their regional subsidiaries have a higher return on assets than the groups as a whole, said the EIB. Perhaps this is an opportunity to take up positions for future growth.

However, not all owners of banks in the region are convinced of that. Although the majority (as many as 55 per cent) of the surveyed groups are planning expansion in the region, one-third intend to reduce their operations. The EIB predicts that owners are beginning to be increasingly selective in their assessments of the markets’ potential and growth opportunities.

The situation in the entire region will be heavily influenced by the policy of the SSM (Single Supervisory Mechanism) European supervision at the European Central Bank, last year’s AQR (Asset Quality Review) and the already commenced Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). This will be the strongest catalyst for the restructuring of banking groups, and consequently changes in the business models and regional strategies.

The restructuring will force banks to raise capital, which is already taking place in many institutions through the sale of assets. Such a decision was made by Raiffeisen, which sold banks in Poland and Slovenia and reduced its presence in Russia.

There is still a fair bit of uncertainty. One factor is the prospect of growth and profitability in substantial markets such as Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia. The second is the necessity of high expenditures in the fight for market share against the largest players in the Czech Republic and in Slovakia. The third variable is the balance of benefits and costs associated with strong competition in the Polish market.

In addition to barriers to entry in the Czech Republic and Slovakia and stiff competition in Poland, low interest rates, and resulting low profits, are a problem in the stable markets in the northern part of the region. At the same time, quantitative easing carried out by the ECB provides easy access to financing and creates the temptation to expand.

The RBI calculated that by the end of 2014 the LTD ratio had declined across the region to 95 per cent, from the 129 per cent observed in 2008. Some of the lowest LTD levels in the region are found in the Czech Republic (77 per cent) and in Slovakia (86 per cent), which provides prospects for credit expansion. In Poland the LTD ratio stood at 107.4 per cent at the end of July 2015.

Game changer

There is growing uncertainty over the impact of China’s economic slowdown and stock market crash, as well as the expected normalization of the Fed’s monetary policy. These are the main two reasons why the Standard and Poor’s rating agency lowered the credit ratings of twice as many issuers as those whose ratings it raised, in the second quarter of 2015. This indicates growing risk on a global scale.

The Chief Economist at Citigroup, Willem Buiter, wrote that the most likely scenario for the global economy in the next two years is a moderate recession that will begin (or has already began, as in the case of Russia and Brazil) in emerging markets. Southeastern Europe has barely caught its breath after the last crisis, and the global macroeconomic situation may stifle it again.

We do not know how risks are reflected in the portfolios of the parent companies of banks throughout the region. If their exposures to commodities, stocks and debt securities yield losses, they will be even more anxious to sell off assets and may decide to exit the region.

At the same time, a survey conducted by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) shows that credit conditions in emerging markets have slipped to levels last recorded in the fourth quarter of 2011. The emerging markets of Europe have so far come out unscathed. However, the boost in lending is threatened by the risk of a hard landing, and then the banks’ hopes of a return to profitability would again be deferred.

This also applies to Polish banks. After last year’s sharp increases, this year lending is growing at a much more moderate pace. Bank prospects are still clouded by the unresolved risk of loans denominated in Swiss francs, whereas in other countries it has either been completely avoided, or the problem has already been solved. Banks are already showing strain. In 2007, return on equity (ROE) in the Polish banking sector came to 22.5 per cent, while by the end of the first quarter of 2015 it was 9.61 per cent. During this period ROA fell from 1.7 per cent to less than 1 per cent.

No matter how the issue of Swiss franc loans is resolved, the deterioration in the profitability of Polish banks appears to be a long-term trend. That, along with owners’ failure to achieve the intended scale of operations, may accelerate decisions on exiting the Polish market.