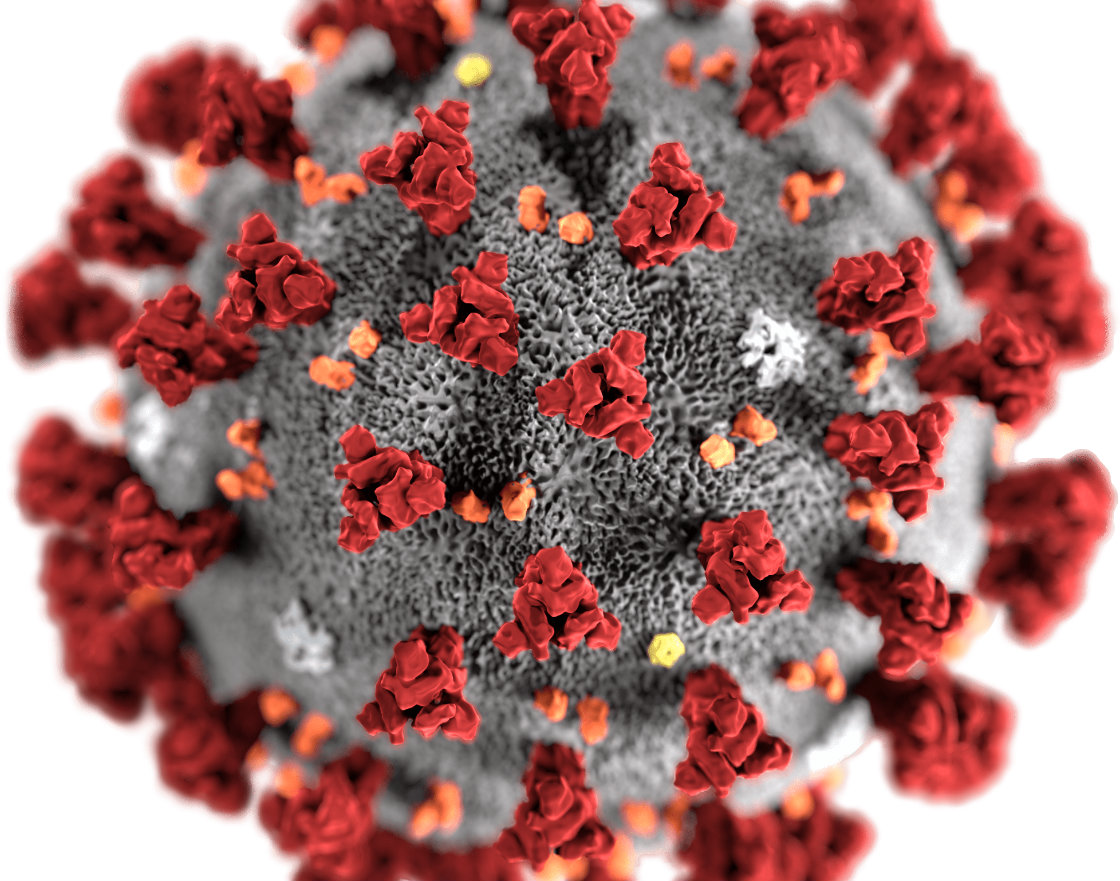

(©CDC/Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM, Public domain)

On December 31st, 2019, the local government in the Chinese province of Wuhan reported that health authorities were treating dozens of cases of “pneumonia of unknown cause.” Days later, Chinese health experts identified a new virus that had been spreading in Asia. About three weeks later, the central government of China imposed a lockdown in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei province, hoping to prevent an outbreak of the virus beyond its original epicenter.

Although recent numbers are showing that the draconian measures imposed by the government in China might have worked in the country, the virus has spread far beyond China’s borders.

According to Worldometer, an independent global statistics provider, there are currently 255,943 cases in 182 countries and territories (as of March 20th, 2020). The global spread of the virus has prompted the World Health Organization to characterize COVID-19 as a pandemic, after it had already declared the outbreak a global health emergency in January.

Global financial markets were the first to react to the outbreak of coronavirus internationally. All major stock indexes, from S&P 500 to Eurostoxx 50 and Nikkei 225 Index registered significant drops. Emerging markets, such as Russia, have been hit particularly hard, given the freefall of the oil prices. Both the Russian stock markets and the RUB are now down around 20 per cent since the start of the year.

Impact on non-financial markets

Although well-performing stock markets are important for the health of any economy, most people are, arguably, more concerned about the performance of non-financial sectors, such as manufacturing, retail or services, which are more directly linked to jobs.

So far, no country in the world has been affected by the impact of SARS-CoV-2 as much as China. The drastic measures imposed by the central government in Beijing effectively brought the country to an economic standstill. According to ING Bank, China’s economy is now experiencing an unprecedented slowdown. “Industrial production fell 13.5 per cent y/y YTD, fixed asset investments fell 24.5 per cent y/y YTD and retail sales fell 20.5 per cent y/y YTD,” writes ING. Moreover, the situation could have been even worse had the iron, steel and copper production been interrupted. “Industrial output was not as bad as fixed-asset investment and retail sales because there was still iron, steel, and copper production in February, otherwise, it would have been a lot worse than reported.”

Although it seems like China has now entered a recovery stage from the coronavirus, there are still some new cases being reported in major cities. This means that retail sales in China are going to recover only very slowly. “Consumers are still wary about going to shopping malls and restaurants. This could continue as there are some imported Covid-19 cases in major cities,” the report says.

Although the retail sector has been hit hard, the picture is much darker for the China’s key sector – industrial production. “Industrial production will continue to be hit in March and April as the spread of Covid-19 in almost all countries means global demand will stop abruptly, and global supply chains will still be broken as factories around the world suspend operations. We are not optimistic about China’s manufacturing and exports,” ING writes.

Global spillover

For a few weeks, since the outbreak of the health crisis in China, it seemed that both Europe and the United States might remain insulated from the crisis. However, this option has already been invalidated. The question everyone is asking now is how much will Europe and US be affected.

For Europe, a major public health crisis is the last thing the continent needs right now. In the Q4’19, the Eurozone saw only a meagre 0.1 per cent of GDP growth, with only a few signs of things getting better in a foreseeable future.

According to a recent study by the Rabobank Economic Research Unit, the main challenge for the Eurozone economy now is that businesses are faced with both a supply and demand shock at the same time. “As output in China falls sharply, the import of Chinese consumer goods and semi-finished goods is hampered. So far, European businesses are mostly experiencing supply chain disruptions directly or indirectly caused by China,” the report reads.

At the same time, the Chinese economic standstill dramatically reduces global demand. “Meanwhile, demand suffers as well. The lockdown of a substantial part of China and a slowdown in growth of the Chinese economy in general leads to lower Chinese demand for German capital goods and cars, for example.”

So far, the European economy has been affected primarily by the falling demand and supply from China. However, as more containment measures are introduced across the continent, Europe could develop a local economic crisis of its own. “For now, this effect is mostly visible in Italy, but it is unlikely to be confined solely to this member state. All over Europe, the outbreak of the virus is leading to cutbacks in „non-essential” business travel, holiday-breaks and events. Moreover, as the financial market reaction swells, households may postpone purchases of durable consumer goods,” the Rabobank Economic Research Unit says.

The question remains what sort of measures to contain the crisis will European governments introduce. This will determine the overall economic impact of the crisis beyond the damage already done by the disruptions in trade with China.

Needless to say, this doesn’t apply to sectors such as tourism, hospitality or transport which are going to be affected either way.

The situation is equally dire in the United States. According to a recent Fitch Ratings report, the sectors of the US economy most at risk are: US energy, metals and mining, airlines, travel services and gaming companies.

However, unlike some major European economies, such as Germany and France, which are highly exposed to China, the US and its major corporations have operations that are relatively US-centric or geographically diversified. This reduces the risk of a major economic crisis caused primarily by trade disruptions with China.

Attempts to curtail the crisis

The United States’ House of Representatives first came to rescue of the American economy on March 4th, when it approved USD8.3bn in emergency aid to combat the impact of the novel coronavirus.

The package included nearly USD7.8bn for agencies dealing with the virus. It also authorized around USD500m to allow public health insurance providers to administer health-related services, mainly directed at the elderly, the New York Times reported.

According to a more recent NYT article from March 18th, Washington is currently considering proposals for a financial bailout worth more than USD2 trillion. This includes President Donald Trump’s proposal to provide direct payments to individuals and small business to keep their operations running and workers on their payrolls during the crisis.

In China, the country’s central bank, The People’s Bank of China, resorted to a stimulus of the financial sector. In particular, on March 13th, the Chinese financial regulator decided to cut reserve requirements for banks, a move that will “free up an additional USD78.8bn in funds that the authorities want banks to lend to companies hit by the outbreak,” Financial Times reported. Similar to the US, the Chinese authorities hope that the freed-up funds will be directed by the banks at smaller businesses that struggle to access bank lending.

Unlike in China or the United States, federal measures are traditionally much harder to implement in the European Union, and the current situation is no exception to the rule. On Monday, March 16th, European finance ministers discussed the possibility of deploying a joint fiscal stimulus to help sustain Europe’s struggling health systems and companies, particularly SMEs. However, the group demonstrated a lack of ability to reach a compromise and failed to adopt the financial stimulus package, which has been demanded by some member states, led by France and Italy.

So, it’s rather up to the individual member states to provide financial support to their respective economies. According to the European Commission, the amount of financial support to the economy provided so far by the individual governments in Europe represents, on average, 1 per cent of the GDP.

Besides the individual national financial packages, the European Commission has pledged to allocate unspent structural funds worth EUR37bn to support healthcare systems, SMEs, sectors and workers most affected by the pandemic.

Similarly, the European Investment Bank is preparing a financial package of EUR8bn in lending for SMEs. There are plans to increase this amount to EUR20bn, Euroactiv reported.

Things to come

What is exactly in the cards for the global economy? The naked truth is that nobody knows. At first, it seemed that the contagion would not spread beyond Chinese borders. Then there were first cases reported in other countries across Asia. At that point, it still felt like the crisis was of a regional character, with a limited impact on countries in Europe or North America. However, over the last couple of weeks, it became painfully obvious that the crisis is global, with an equally borderless impact on economies across the globe.

Since no one can predict the future spread of the coronavirus, it is impossible to assess the overall impact the related health crisis is going to have on the global economy. Instead of giving any definitive answers, organizations that are in the business of making economic forecasts break down their assessments for the future economic growth into distinct categories based on “likely scenarios”.

One such assessment, titled “Coronavirus: The world economy at risk”, was published by the OECD on March 2nd. In the report, the OECD team presented two distinct scenarios of the potential economic effects that could result from the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in China and the risks that it spreads to other economies.

The so called “base-case scenario: a contained outbreak”, considers “the effects of a short-lived, but severe downturn in China, assumed to fade away gradually by early 2021. The key assumption of this scenario is that the global economy would be affected mainly as a result of an economic slowdown in China, and the subsequent weakening of supply and demand of the country’s economy. But domestic supply and demand of other major economies would be less affected, which would prevent a full-on global economic slowdown.

Then the first scenario looks as follows: pandemic peaks in China in the Q1’20 and outbreak in other countries is contained, subsequently global growth slows down by 0.5 per cent from 2.9 to 2.4 per cent. Most of this decline stems from the effects of the initial reduction in demand in China. Global trade is significantly affected, declining by 1.4 per cent in the H1’20, and by 0.9 per cent in the year as a whole. The overall impact of lower commodity prices is broadly neutral. Commodity exporters are hit by a reduction in their export revenues, but commodity-importing economies benefit from lower prices. The first scenario would thus mean a global economic slowdown due to China’s economic troubles, but not a major global economic crisis.

The second scenario, titled “domino scenario: broader contagion”, projects a more pessimistic view of the future global economy. The image is as follows: a longer lasting and more intensive coronavirus outbreak spreads widely throughout the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and North America. Economic growth is down by 1.5 per cent. Domestic demand in most of Asia-Pacific economies, including Japan and Korea, and private consumption in the advanced northern hemisphere economies is reduced by 2 per cent (relative to baseline) in the Q2 and Q3’20.

In other words, the extent of the economic crisis accompanying the health crisis is going to be determined by the ability of governments to contain the spread of the virus without doing too much damage to their economies.

China now seems to have finally brought the virus under control, but it has only been able to achieve it by essentially bringing its economy to halt, sending ripples across the global economy. It now remains to be seen how other key centers of the global economy, such as Europe, United States and countries in Asia-Pacific deal with the crisis. Their response will determine which scenario of the future of the global economy will eventually materialize.

Filip Brokeš is an analyst and a journalist specializing in international relations.