There are other stakeholders in the education system. Teachers defending their position guaranteed in the Teachers’ Charter, authors and publishers of textbooks, and organizers of social and private primary and middle schools. Their interests are often contradictory, and the compromise – in other words the current education system – is far from perfect.

Problem for municipalities

In 2016, the Polish state spent EUR14.4bn on education, upbringing and care. This is more than the total expenditure on defense, internal security and the justice system – the three basic functions of the traditional state. It was not until the end of the 19th century that the state recognized education as one of its functions – first in the United Kingdom, then in other countries. Today, expenditure on education is one of the most important items of the budget.

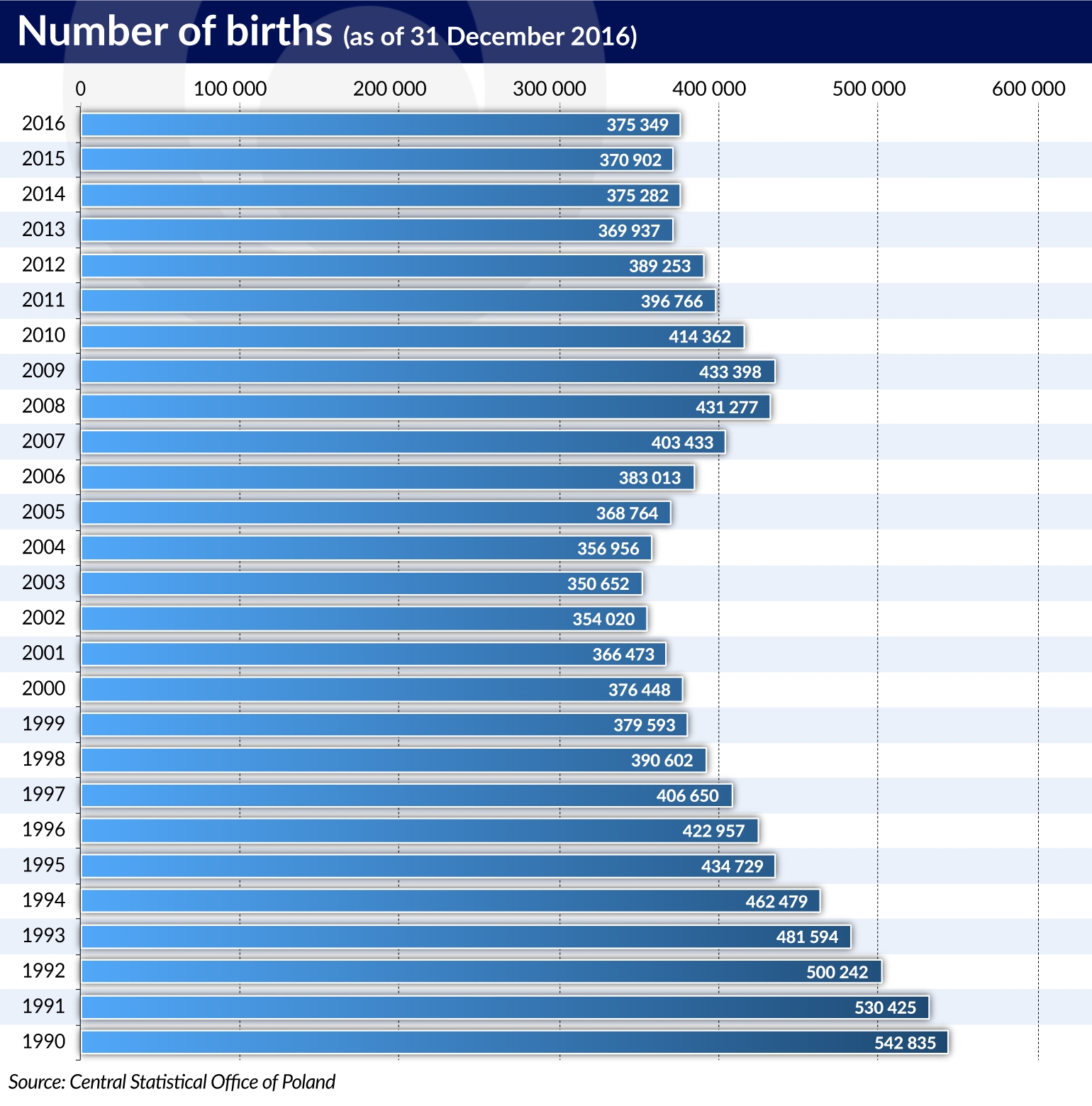

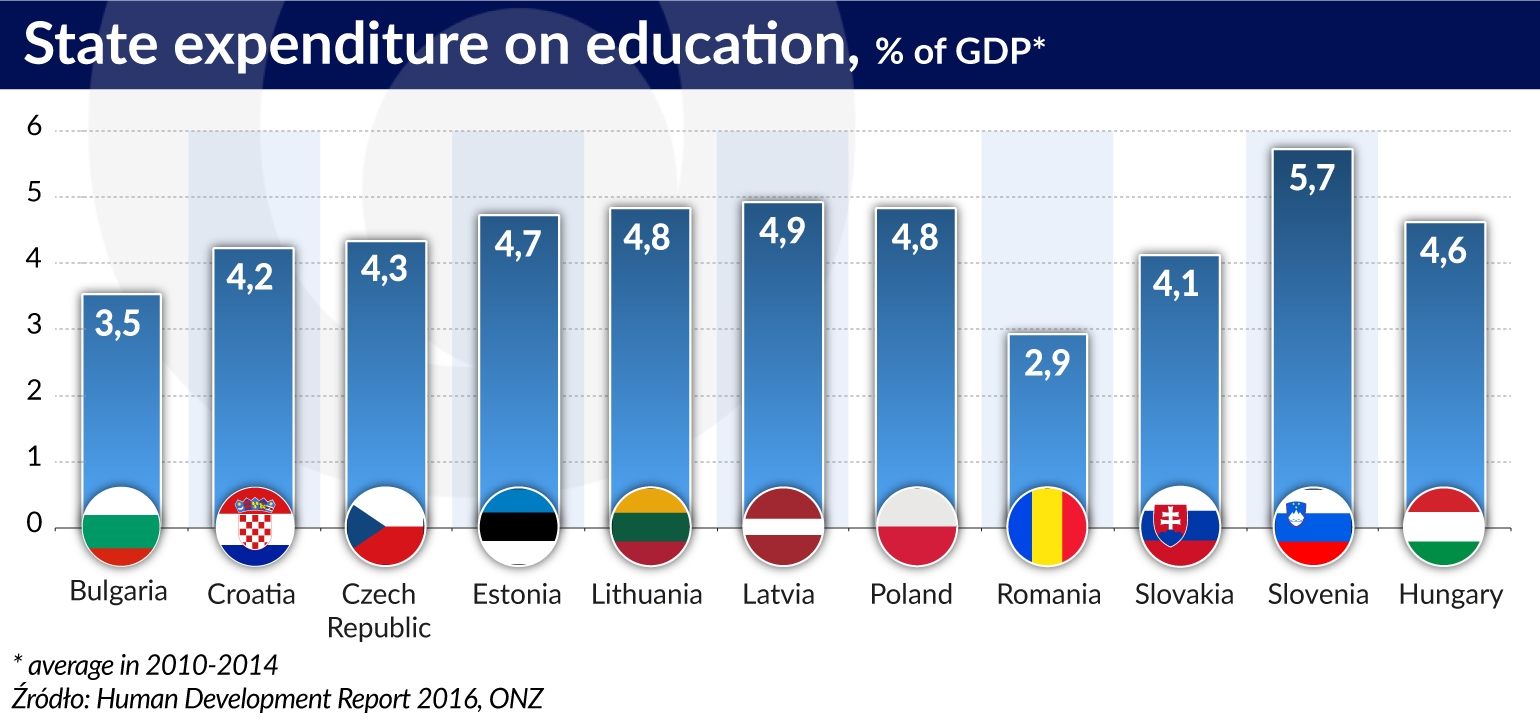

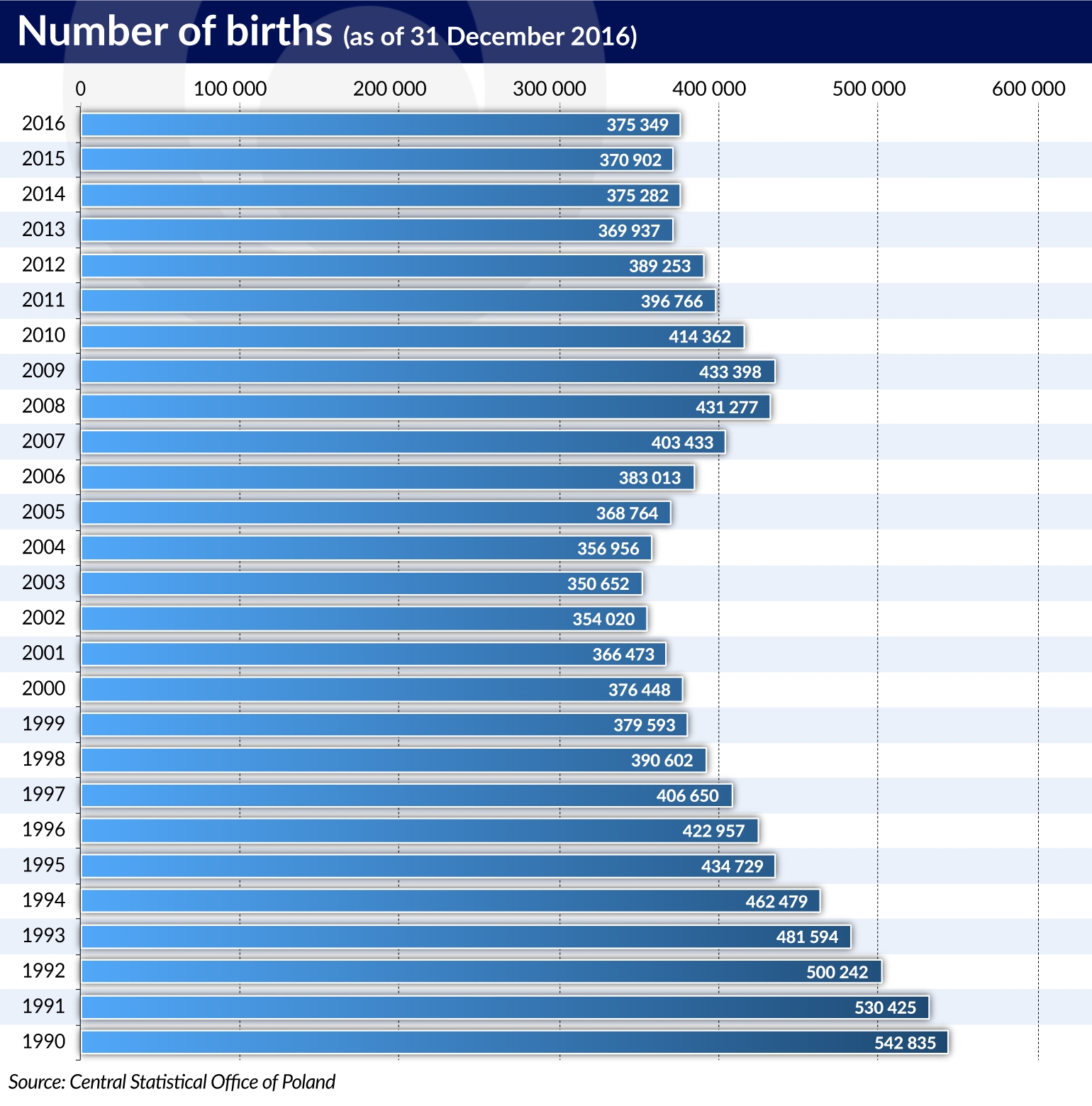

The ratio of expenditure on education, upbringing and care to GDP has been declining for several years. In 2016 it was 3.3 per cent of GDP compared to 3.7 per cent in 2015 and 4 per cent in 2013. The relative decline in expenditure on education, upbringing and care is a result of demographic changes. Demographic fluctuations, occurring in Poland for over 60 years, are a serious problem. Years of demographic boom are followed by years of demographic slump. Many school buildings built in the 1960s under the “1000 schools for the millennium of the Polish state” campaign are today used for other purposes.

In September, children born in 2010 or (a smaller number) in 2011 will enter the first class of primary school. These are cohorts of a small demographic boom which began in 2006 and was an echo of the larger demographic boom of the 1980s. This was a weak echo that culminated in 2009. Nevertheless, there are 50,000 more cohorts of 2010 than cohorts of 2003, while successive cohorts are a dozen or so thousand fewer. Currently the most numerous cohorts – born in 1983 (674,280 people) – have already been active in the labor market for several years.

Demographic fluctuations are problematic, above all, for local governments, since they are responsible for organizing education, for which they receive a subsidy from the state central budget proportional to the number of pupils. When cohorts of the demographic booms started school there was a shortage of rooms and teachers, who had to work overtime. Today, many teachers have the problem of an incomplete teaching load.

The law imposes on local government units the task of organizing education. The task of municipalities is to establish and run public pre-schools, including special pre-schools, except for special needs schools. However, the tasks of the poviats (counties) include the establishment and running of the following:

- public special needs primary schools and special needs middle schools;

- upper-secondary schools;

- sports schools, continuing education institutions, including practical education, and also psychological and pedagogical counselling centers, as well as providing adequate education for children and young people with mental and physical disabilities.

In 2016, local governments received subsidies for the fulfilment of education tasks in the amount of EUR9.7bn (in 2017 an education subsidy of EUR9.8bn is planned). The state budget spends almost EUR1bn on education on top of the education subsidy, e.g. on running the school inspectorates and teachers’ training. The education budget finances almost 80 per cent of current expenditure earmarked for the realization of the educational tasks of local governments (excluding public pre-schools and transporting pupils). Local governments must finance the rest from other sources.

The subsidy per pupil amounts to EUR1,249 and is divided according to the type of school and age group of the pupils. If the number of pupils decreases (because of a demographic slump or young people leaving the municipality), the subsidy decreases, but the education costs, which the municipality must meet, do not necessarily decrease.

Expenditure on pre-schools is to be met from the remaining income of local government units, and not from subsidies. As statistics show, this expenditure is constantly growing, among others, due to the introduction of universal pre-school education (compulsory for five-year-olds). Expenditure on pre-schools consumes over 10 per cent of all expenditures of local governments on education. Last year the Minister of Finance released funds from the reserves amounting to a total of over EUR351.5m intended to be provided to municipalities as a targeted subsidy for the running of pre-schools. In the 2017 budget, EUR328m was allocated for increasing access to pre-school education.

It is also the municipality’s responsibility to provide free transport and care while transporting a child to and from school or refund the transport costs of public transport of the child and it’s guardian. transport. The municipalities have to finance these obligations themselves.

Teachers’ remuneration constitutes the main part of the education costs. The average (median) gross salary amounts to EUR763.6 per month. Every second teacher receives a salary ranging from EUR631.9 to EUR976.6. 25 per cent of the worst paid teachers earn a gross salary of less than EUR631.9. The 25 per cent of the best paid teachers earn more than EUR976.6gross (data from Sedlak & Sedlak). Therefore, the salaries are not high, but local governments complain about excessive privileges resulting from the Teachers’ Charter, e.g. the year-long paid holiday that teachers are entitled to during their career.

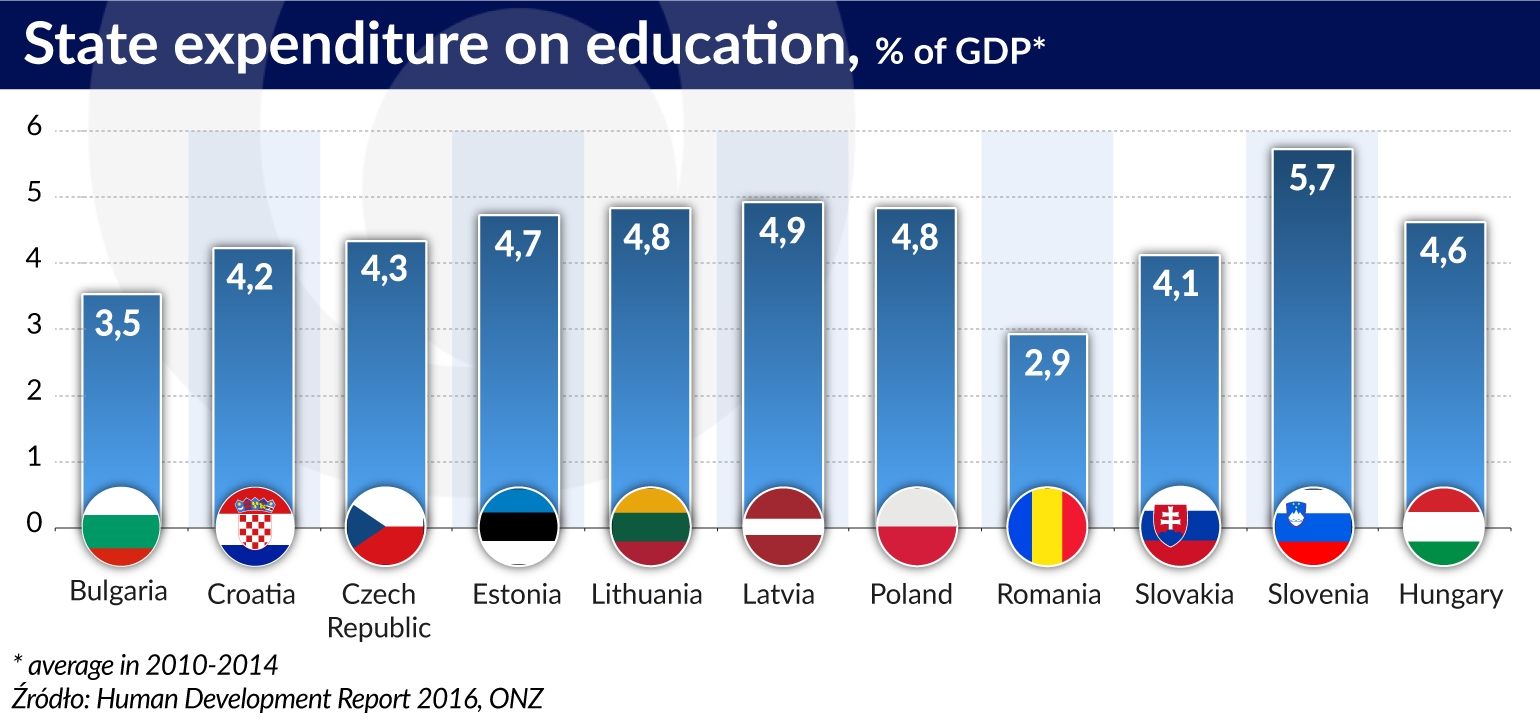

Poland, along with other Central and Southeast European states, has solved the illiteracy problem over half a century ago. However, it needs to be noted that in 1931, 23,1 per cent of adults were illiterate, and the illiteracy rate in the rural areas was as high as 27,5 per cent. Similar to the rest of the EU counties, there exists a compulsory education system for young children and teenagers, which lasts from 9 to 13 years in total. Education in primary and secondary schools is free and expenditures for education range from 2,9 per cent GDP in Romania to 5,7 per cent GDP in Slovenia. In the Western European countries expenditures for education usually exceed 5 per cent GDP.

Parents pay for better education

According to research of household budgets, households spend only 0.9 per cent of their total expenditure on education. In working class families this is 1.2 per cent, and in self-employed families it is 1.5 per cent. These figures are surprisingly low and it is difficult to believe that they are correct, taking into account the prospering private tuition market and the numerous non-public schools in which the monthly tuition fees amount to approx. EUR234.3.

The private tuition market is to a large extent a grey zone, the size of which one can only estimate approximately. The Minister of Education Anna Zalewska claimed that families spend approx. EUR937.2 on private tuition. That would mean that the cost of private tuition is over 6 per cent of what the state spends on education.

According to data of the largest Polish website with classified ads for private lessons, e-korepetycje.net, the most adds are from teachers of English and Chemistry. The price per hour varies, depending on a town and a subject, from EUR4.7 to EUR11.7, although of course there are also offers beyond this range.

According to the law, teachers – both professional and, for example, students – should declare income from private lessons to the tax office. A private tutor does not have to set up a business – it is enough to pay each month an advance on income tax and submit the annual tax declaration form in which income from such activity and the paid advance on tax are declared. The tax rate is 18 per cent.

Apart from private lessons, many families pay for lessons for their children in private language schools. This market is estimated at approx. EUR468.6m annually. Nowadays, fluent English is considered a necessary requirement (although not the only one) to get a good job. After all, without a knowledge of languages it is difficult to use internet, nowadays the most important source of information.

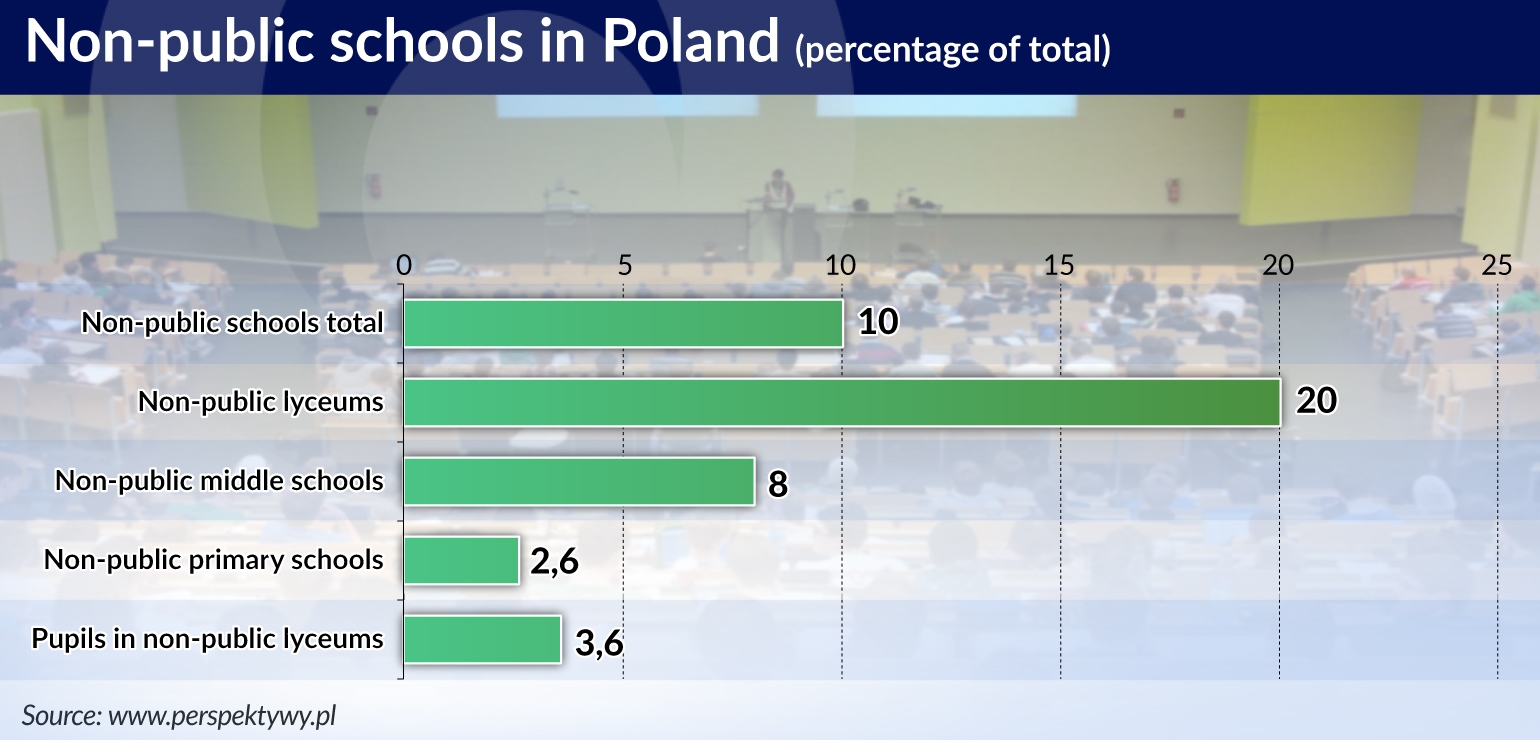

Richer families believe that the best way to guarantee their child a good start in an adult life is education in a non-public school. According to the Centre for Research on Prejudice, in 2014, 48 per cent of Poles rated non-public schools higher, while 36 per cent rated public schools higher. Every sixth upper-secondary school for Polish youth is a non-public school. However, only 4 per cent of secondary school students attend such schools, since they are usually small institutions with smaller classes than in public schools. Non-public schools also differ among themselves. There are private schools established in order to make profit, and social schools, operating on a non-profit basis.

The most expensive are foreign schools operating in Poland. For example, the annual fees of the International American School range from EUR7,497.8 to EUR11,949.6, depending on the class. The annual fees in German and French schools are over EUR4,686.1. It is necessary to pay approx. EUR2,343 annually for education in the best Warsaw social schools; outside of Warsaw they are much cheaper – fees range from EUR468.6 to EUR1,405.8. Catholic schools are relatively cheap – they also offer boarding.

For less affluent families, private tuition and non-public schools are beyond their financial means. At the beginning of the school year they already have relatively high expenditure on school books and accessories. According to research by Barometr Providenta, Polish families will spend on average EUR121.9 per child this year on preparing the child to go back to school. Every fifth parent will be able to afford to spend between EUR117.1-164, and 14 per cent will spend over EUR164. Most families finance the costs of equipping their child for school from their own pocket, while 34 per cent use the funds from the government’s Family 500+ program (child benefits program) for that purpose. Approx. 28 per cent use their savings or ask family for help, and 2 per cent take a loan.

Employers unhappy

“The employees who we recruit require training from scratch. The state education system, which we pay for out of our taxes, provides recruited employees no more than 10 per cent of the required skills,” says Krystyna Boczkowska, CEO of Robert Bosch Sp. z o.o., a representative of the Bosch Group in Poland.

This is a typical view among employers. They complain not only about the difficulty in finding employees, but also about the mismatch of school-leavers’ skills to the needs of the market. It is different in Germany, for example, where there is a network of vocational schools of various grades, which cooperate with enterprises. German employers organize and sponsor schools and provide them with the vocational teaching staff and the possibility of work placements.

Vocational education was partly liquidated in Poland under the education reform of 1999. What remained was 3- and 4-year technical and vocational schools, while the previously existing vocational schools have disappeared. It was assumed that young people should above all gain general knowledge, thanks to which they will be able to gain additional skills and qualifications during their career. Therefore, higher education has become more widespread, although quality has declined as a result of its mass character.

In Germany the problem is solved thanks to close cooperation between industry and the schools, but such cooperation in Poland does not exist. What’s more, new professions are appearing related to IT, precision mechanics, and robotics, which the sectoral vocational schools will not teach, because experts in these fields are scarce. There is a risk that graduates of the sectoral schools will turn out completely unnecessary for the labor market and will have to obtain their real qualifications from scratch during work.

Today the pendulum has swung the other way. First and second degree sectoral vocational schools are to be established. It is expected that a large proportion of young people, who earlier would have chosen comprehensive secondary schools, and later schools of higher education, will now continue their education after primary school in the sectoral vocational schools. This is to be a remedy for the lack of mid-level staff in industry and construction.