Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(By DG/CC by Vladimir Yaitskiy)

Business news of the last few weeks: Ukraine buys cheap gas in Germany, the government may order the banks to sell foreign currencies, agreements with Shell, Chevron and ExxonMobil still this year, foreign investors complain that the government favours the oligarchs’ companies, companies with links to the president’s son have taken over factories worth USD 10 million without paying a cent, the grey market accounts for 34% of GDP, online purchases have risen to USD 4 billion. These few headlines sum up the essence of Ukraine’s situation – the wish to escape the energy dependence on Russia and the problems of foreign debt, grey market and nepotism, attracting and rejecting investors, modern technologies and oligarchy.

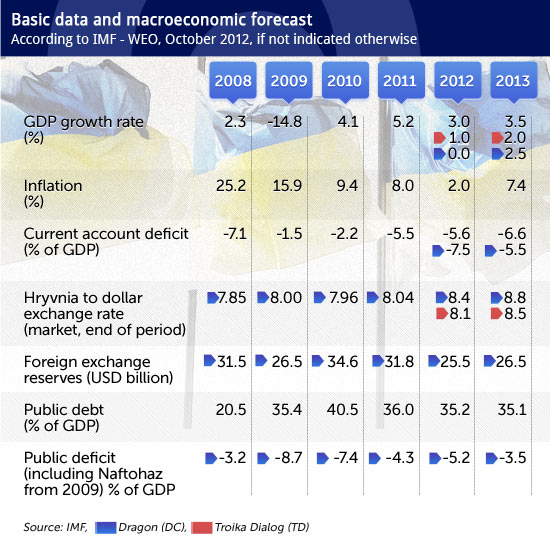

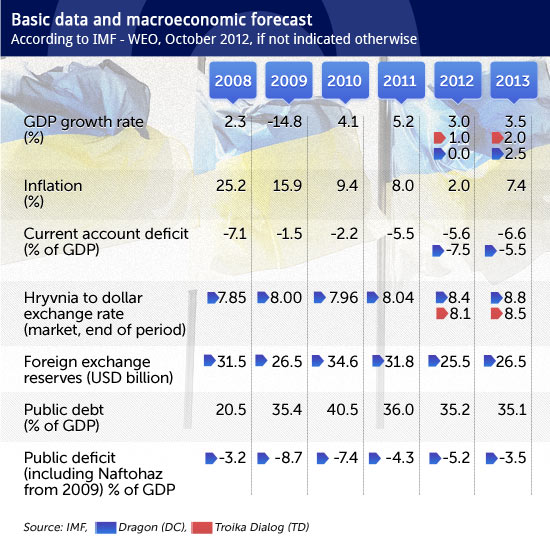

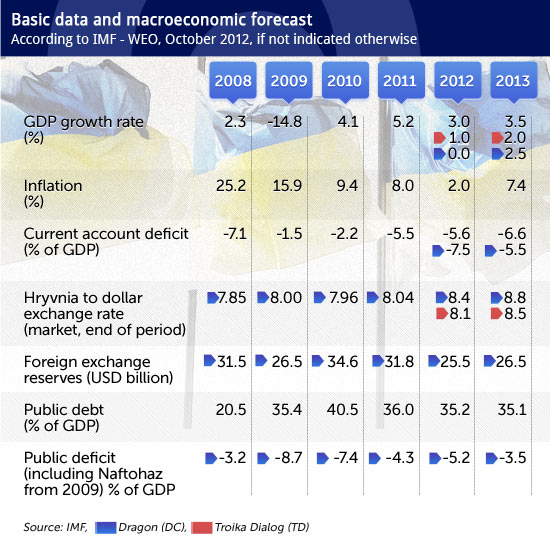

The crisis of 2009 had severely affected our eastern neighbour, whose GDP dropped by almost 15%. However, in recent years GDP has been rising again, at a pace of 4-5% a year. This year started off well, but the third quarter saw a slump when GDP declined by 1.3% compared to the third quarter of 2011. The forecast for the coming months is bad and that for the next year uncertain (table).

The uncertainty was not dispelled by the result of the October election won by the presidential Party of the Regions headed by Viktor Yanukovych. It could not have been dispelled, as both the ruling party and the opposition are deeply entangled in dealings with the oligarchy and it is difficult to conduct reforms in a poor and politically divided country, even if a willing reformer cropped up, which is not at all a given.

It seems that Ukraine’s gravest macroeconomic problem is external imbalance and a fixed exchange rate regime. This is the source of the mounting pressure on a devaluation of the hryvnia, as well as the external sovereign debt (USD 9 billion to be repaid next year) and the current account deficit (at the moment amounting to 7.5% of GDP).

Ukraine has not entered into agreement with the IMF on further cooperation, but must repay USD 5.5 billion to the Fund in 2013. The IMF expects realistic prices of gas and energy and a floating exchange rate to be introduced, to which the government says “No”. The talks on the agreement of association with the European Union stalled after the leader of the opposition Yulia Tymoshenko was sent to prison, so Ukraine cannot hope for help from the EU.

The tense balance-of-payment situation has at least two important effects. Firstly, the interventions of the central bank, NBU, aimed at protecting the hryvnia, have reduced the liquidity of the banking system and hampered lending to the economy – interest rates exceed 20%. Secondly, panic may erupt at any time. Ukrainians occasionally flock into banks – recently in September and October – to exchange hryvnias into US dollars. Foreign currency reserves decreased from USD 38 billion in summer of 2011 to less than USD 27 billion in October this year following purchases made by the public and the intervention of the NBU on the foreign exchange market. The current amount of reserves would cover just 3 months of imports.

In order to bring down the soaring and persistent inflation, which has been running at more than approx.10% a year, the government in Kiev fixed the official exchange rate at the beginning of 2010 at 8 hryvnias per US dollar. The market has accepted this for many months and the inflation in the second quarter of this year fell below nought. However, starting from May, the exchange rate on the interbank market has been weakening. Today it is has exceeded 8.20 hryvnias and many analysts expect that the crawling devaluation will take the exchange rate up to 9.5 at the end of next year.

“Devaluation is inevitable. The reserves are shrinking, the trade deficit is growing and people continue to buy hard currency (though they are far from panic)”, says Wojciech Konończuk, the head of the Ukrainian section at the Centre for Eastern Studies.

In the pessimistic scenario, the devaluation will take the rate up to 10 hryvnias per USD, predicts the Dragon Capital investment bank. However, analyses by Deutsche Bank show that the real appreciation of the hryvnia, mainly as a result of the fixed exchange rate, amounted to only approx. 15% since 2008, which means that there is no risk of a dramatic fall in the value of the currency.

It is good from Poland’s point of view, since a rapid devaluation would also hamper Polish exports to Ukraine, which have been growing robustly in the last two years (this year they increased, in EUR terms, by 20%) but have not returned to their pre-crisis levels yet.

Regardless of what will happen to the exchange rate, only the optimists in the IMF and the government believe in economic growth of 3.5% in Ukraine next year (Dragon forecasts 2.5% and analysts of Troika Dialog – 2.0%).

Internal problems are enhanced by weak economic conditions in Europe, in particular in terms of demand for the main Ukrainian export product, i.e. steel products. Global prices of coal are also decreasing. Prices of cereals remain high but agri-food products account for only 19% of Ukrainian exports, while metallurgical products for 32% and mineral products for 15%.

As a result, industrial output in Ukraine was lower in September than a year before and the forecast for the coming months and quarters is negative. Price competitiveness could be boosted with a devaluation of the hryvnia, but the government attempts to avoid it. The memory of multiple bankruptcies of companies with large foreign-currency debt after the nearly- 50% slump in the hryvnia in 2008 as all too vivid; and so is that of the ensuing dramatic fall in living standards.

The latter is very important since the general public outside Ukraine tends not to realise how poor a country Ukraine is. The nominal GDP per capita amounts to USD 3,624, compared to Poland’s USD 13,469 (IMF data, 2011). Even adjusted for purchasing power, the difference is threefold (Poland: USD 20,184, Ukraine: USD 7,222 PPP).The average salary in Ukraine is below 3000 hryvnias, i.e. approx. USD 350, which is less than one third of the salary in Poland. The median is even lower, despite a fast recovery in salaries after the 2009 crisis and in the pre-election period.

Yanukovych’s government may be guilty of populism, a streak illustrated by increasing social benefits and salaries not underpinned by productivity gains, by maintaining understated prices for energy or giving general preference to domestic companies, which discourages foreign investors. But one must bear in mind that the populism stems from fears of protests by the extremely poor, as compared to other European countries, population. GDP per capita in Ukraine is lower than in China, Russia, Belarus, Albania, Macedonia or Bosnia.

This, of course, cannot justify the thoroughly corrupted system. The country is ruled by oligarchs and the position of President Yanukovych vis-a-vis these circles is much weaker than that of Putin in Russia.

The fortune of the richest oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov, who supports Yanukovych, is estimated at USD 16-25 billion, while the next 15-20 persons on the list have only just over USD 1 billion each, according to the local press (Korrespondent, Focus). Their assets tripled within just three years, from 2009 to 2011, though to a various extent. This depended of course on their relations with the president and the government. And of course it is out of the question that President Yanukovich, who has close links with some oligarchs, should do them any kind of harm.

Together with his two sons, he tries to set up his own “clan”. There is, for example, a straightforward explanation to the harassment of foreign investors interested in renewable energy, involving obstruction of land purchase or connection to utility networks, as well as the recently imposed obligation to purchase equipment produced locally. Well, these are investments in green energy, while the three main producers of wind turbines include one connected to the minister of construction, a company belonging to Akhmetov and a producer who, according to the media, has links to the minister of security and defence.

However, some oligarchs are not happy with Yanukovych, in particular with his decision to suspend the negotiations on the association with the European Union, as it results in their losses. The divisions between the oligarchs have a bright side, too, since rival factions finance their own media thus ensuring a considerable freedom of speech and pluralism.

Nevertheless, Ukraine pays a high price for the oligarchic system in the form of an obsolete structure of the economy and exports based on raw materials, lack of effectiveness and monopolisation. The World Economic Forum competitiveness report places Ukraine in the 73rd position (Poland is in the 41st place).

What will the immediate future bring? Recession in the next quarter is almost certain and financial problems highly likely.

According to Konończuk, the resumption of cooperation with the IMF is one of the post-election priorities of the Ukrainian government. “I think that the authorities will decide to raise the price of gas for the public, but probably not to the extent required by the IMF and probably in several stages”, he says. A well-informed journalist of the English language Kyiv Post, Jakub Parusiński, believes that the agreement with the IMF is not an option right now. “Prime Minister Azarov on many occasions emphasized that the government will not increase the price of gas for households”, he asserts.

As regards the agreement on the association, the expert of the Centre for Eastern Studies believes that there is no chance for it to be signed until the presidential election in 2015. Parusiński is less sceptical: “The agreement with the EU may be signed in the summer of 2013”.

These divergent opinions of experts are yet another proof of the unpredictability of the Ukrainian policy.

Apart from the macroeconomic problems, corruption, bureaucracy (despite a considerable improvement of its position, Ukraine is in the 137th place in the Doing Business ranking, while Poland in the 55th) and uncertainty are equally dangerous for Ukraine. Uncertainty hampers investment and modernisation. Foreign investors demand a high risk premium, some of them back out (this year foreign investment is lower by one third).

High interest rates drag on domestic investment, while domestic consumption is reduced by recession. Nowhere to turn for help. Hospody pomyluj, (or Lord, Have Mercy).