Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(By DG)

The European Commission forecast published in early November is not favourable for Poland. The experts of the Commission lowered their growth forecasts for Poland and expect that GDP will grow by 1.8% in the second half of this year and by 2.4% in the entire 2012. In 2013, the projected growth will be 1.8% and in 2014 – 2.6%.

As a matter of fact, the entire Europe is growing more slowly. This year, according to the European Commission, only the following countries will grow faster than Poland: Latvia (4.3%), Lithuania (2.9%), Slovakia (2.6%) and Estonia (2.5%), whereas next year: Latvia (3.6%), Estonia (3.1%), Lithuania (3.1%), Romania (2.2%), Slovakia (2%) and Sweden (1.9%). The euro area economy will shrink by 0.4% this year and will grow by just 0.1% next year.

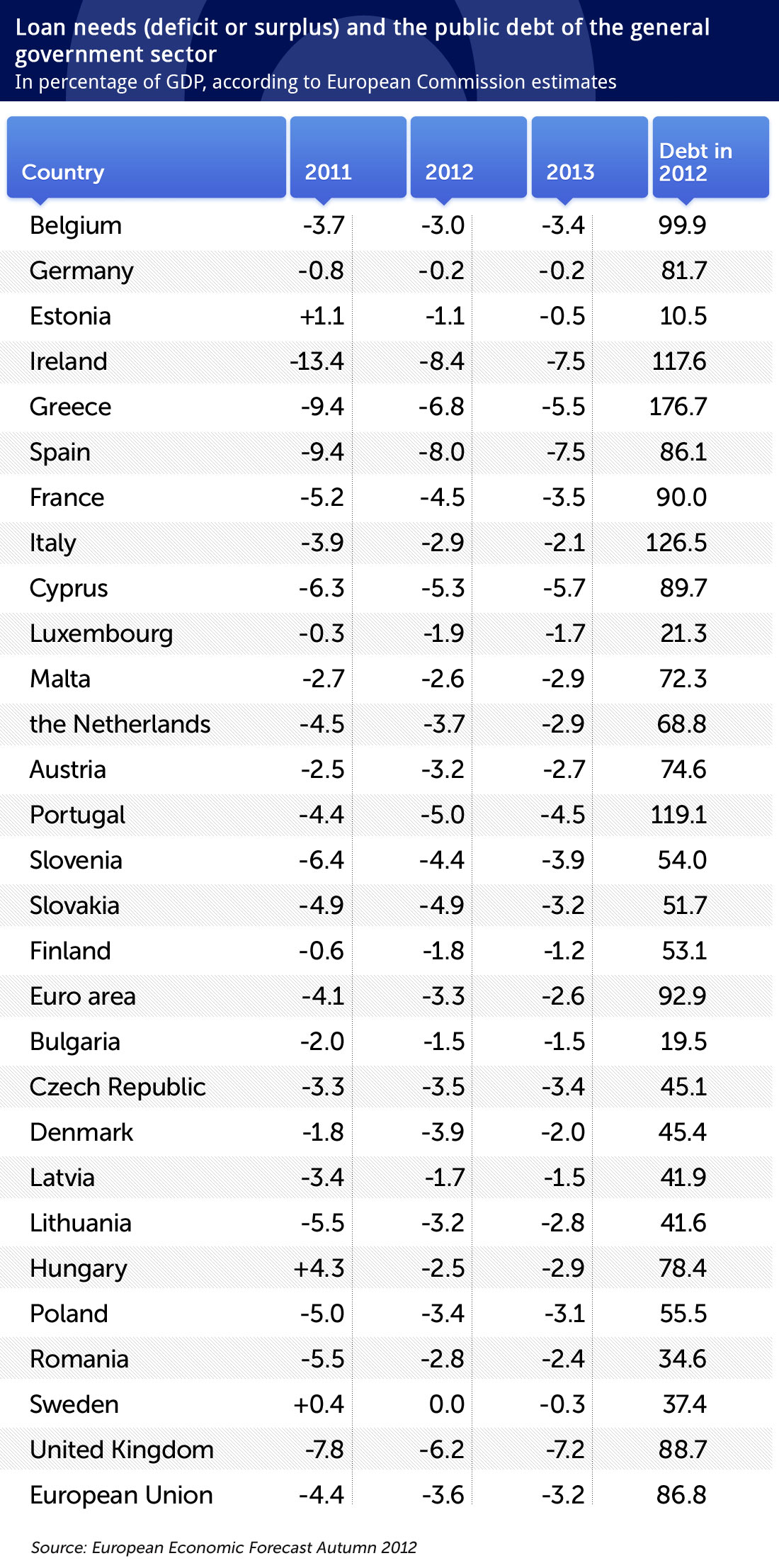

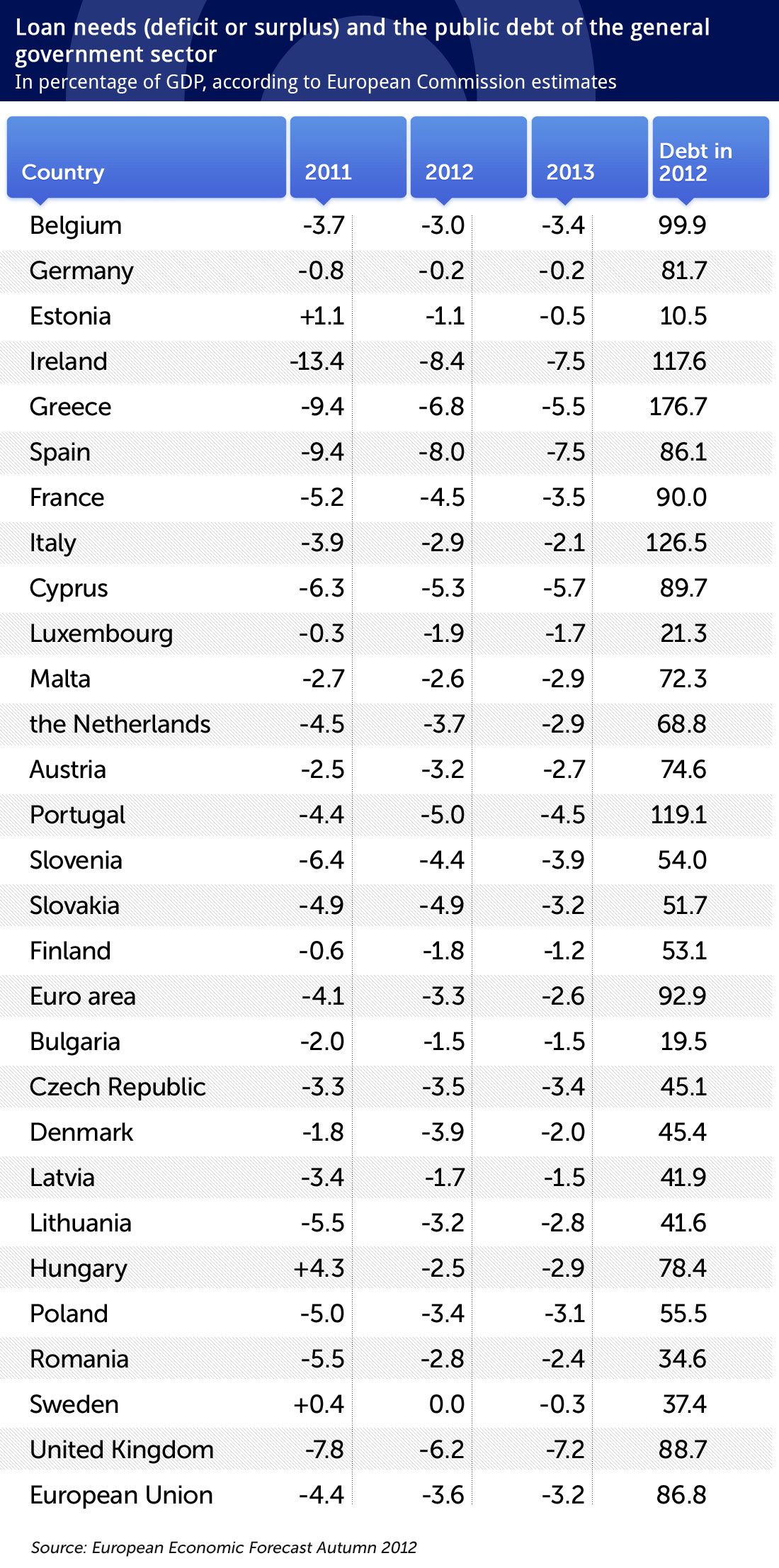

The European Commission also increased its forecast of the public finance deficit for Poland to 3.4% of GDP this year and 3.1% next year, against its spring forecast of 3% and 2.5% of GDP, respectively. The European Commission estimates that Poland will reduce the deficit to 3% in 2014. This means that our country will meet the deficit criterion laid down in the Maastricht Treaty in two years’ time.

Nevertheless, the Polish Ministry of Finance considered the forecast to be a signal that the excessive deficit procedure against Poland may be abolished next year. According to Ludwik Kotecki, the chief economist of the Ministry of Finance, the abrogation of the procedure will be possible after the European Commission deducts the costs of the pension system reform, which will result in the finance sector deficit at approximately 3% of GDP.

The Minister of Finance Jacek Rostowski also said that he was convinced that the European Commission would take into account the fact that the deficit is partly due to the transfer of contributions to open pension funds (OFE) and would abrogate the EDP against Poland next year. At the same time Minister Rostowski declared that Poland intended to fulfil the Maastricht criteria concerning the deficit already in 2013.

The excessive deficit procedure was laid down in the Stability and Growth Pact of 1997, which was amended in 2005. It is also provided for in Article 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The procedure is initiated if the deficit of the general government sector exceeds 3% of GDP or if the public debt in this sector is higher than 60%. The second criterion had not been taken into account until 2008. When the Stability and Growth Pact entered into force, only several EU countries had the debt below 60% of GDP.

If the European Commission finds an excessive deficit, it issues an opinion and a recommendation to the Council of the European Union. The Council decides whether to launch the excessive deficit procedure. If it decides to initiate the procedure, it issues recommendations regarding actions that the country should take to reduce the deficit. It also defines the deadline for the correction of the excessive deficit. In its recommendations, the Council requests the Member State to achieve a minimum annual correction of at least 0.5% of GDP.

The European Commission and the Council of the European Union do not have to initiate the excessive deficit procedure if they consider that the deficit is the result of an unusual event outside the control of the Member State, or a severe economic downturn (recession or a cumulative fall in production in a situation of very low growth).

The assessment of the fiscal situation of a given country also takes into account the economic policy in the context of the Lisbon agenda. In particular, it takes into account the support for research and innovation, developments in the medium-term budgetary position, particularly fiscal consolidation efforts in „good times” and reform of retirement pension schemes, involving the creation of the fully funded pillar.

The decision to initiate the procedure is therefore not automatic. Nor is the decision to abrogate the procedure. If the Member State concerned fails to comply with the recommendations, the Council may decide to proceed to the next step of the procedure, with its final step being the imposition of financial sanctions in the form of a non-interest-bearing deposit, which is then converted to a non-refundable fee.

The deposit includes a fixed component equal to 0.2% of GDP, and a variable component equal to one tenth of the difference between the deficit (expressed as a percentage of GDP in the year in which the deficit was deemed to be excessive) and the reference value (3%). In subsequent years, if the country is still not abiding by the recommendations, the Council may decide to intensify sanctions by requiring an additional deposit. However, the annual amount of deposits may not exceed the limit of 0.5% of GDP.

The Public Finance Act, amended in 2009, imposes limits on fiscal policy when the country is subject to the excessive deficit procedure. Article 112c of the Act stipulates that in the case of EDP the government cannot pass bills:

1) laying down exemptions, reliefs and reductions whose financial effect may consist in the reduced income of public finance sector entities in relation to the amounts resulting from the applicable regulations;

2) resulting in increased government spending, stemming from existing regulations.

These provisions of a sovereign act, though consulted with the European Union, tighten the economic and social policies of the country. The Act reduces the room for manoeuvre of the Council of Ministers which is not allowed to initiate acts deteriorating the condition of public finance. It cannot stimulate the economy by reducing taxes or contributions which add to labour costs or introduce the necessary reforms if they would pose a threat to the budget.

In his so-called second exposé, Prime Minister Donald Tusk put forward a number of solutions that, if implemented, would gradually increase the state expenditure or reduce its revenues. Perhaps the Prime Minister assumes the possibility of such an interpretation of Article 112c of the Public Finance Act that the proposed acts will not interfere with it. It is also possible that the government hopes for a quick abrogation of the EDP against Poland which was suggested by the Minister of Finance.

An example of a bill interfering with Article 112c is the extension of maternity leave announced by Prime Minister Tusk. Work on the bill is underway.

Also tax reliefs proposed by the majority of political parties to stimulate investment or accelerated depreciation of capital expenditure would result in lower tax revenues. One can of course argue that in the medium term the effect need not be negative for the budget, but the introduction of reliefs would be contrary to the letter of Article 112c.

The same applies to ideas for boosting employment – by suspending the collection of social security (ZUS) contributions in the case of employing graduates and other specific groups of employees.

The VAT cash accounting scheme for small companies that the government is currently working on is also in breach of Article 112c.

While reducing the contribution transferred to open pension funds (OFE), the government declared that it would introduce incentives in the tax system to save in the third pillar. The incentives have not been introduced as yet. Such incentives, although desirable, would entail a gradual reduction of state revenues, and thus would violate the provisions relating to the EDP.

Even if the European Commission agrees that a part of the pension reform costs should be deducted from the general government sector deficit and as a result the deficit falls below 3% of GDP, this will not imply an immediate decision on abrogation of the EDP against Poland. Several EU Member States have a lower deficit than Poland and are still subject to the procedure.

During the recession (2009), most of European countries exceeded the permissible limits and were subject to the excessive deficit procedure. Only three countries managed to escape it: Estonia, Luxembourg and Sweden. On 12 July 2011 they were joined by Finland, because the European Commission concluded that it met the criteria of a low deficit and closed the procedure it had initiated a year earlier.

On 22 June this year, European Union finance ministers (Ecofin), in accordance with the recommendation of the European Commission, decided to abrogate the procedure against Bulgaria and Germany, confirming that those two countries have permanently reduced the deficit below the allowed limit of 3% of GDP.

Bulgaria reduced its deficit from 3.1% of GDP in 2010 to 2% in 2011. According to the autumn forecast, the deficit will continue to decrease to 1.5% of GDP in 2012 and 1.5% in 2013. Bulgaria has a much lower public debt than Poland – 19.5% of GDP. The Polish debt reaches 55%.

Germany cut down the deficit from 4.1% in 2010 to 0.8% of GDP in 2011. According to the May forecast, the deficit of Germany will amount to 0.9% of GDP in 2012 and 0.7% of GDP in the following year. However, Germany’s debt is relatively high, i.e. 81.7% of GDP. It is expected to decline, according to European Commission forecasts, to 80.8% next year and to 78.4% in 2014. It will still exceed the requirement of 60% of GDP.

The regulations which entered into force in the European Union on 13 December 2011 (the so-called “six-pack” – five regulations and one directive) stipulate, however, that Member States may be subject to an excessive deficit procedure even if their deficit is below 3% of GDP if the difference between their debt and the level of 60% is not reduced by 1/20 per year. Germany meets this very requirement. Despite the strong commitment to support the indebted countries, Germany pursues a debt reduction policy and cuts down its debt at a sufficient pace.

A separate case is Hungary, which in 2011 generated the highest public finance surplus in the European Union, i.e. 4.3% of GDP but is still subject to the EDP. The surplus was the result of a takeover of a large part of pension fund savings by the public finance sector. In June 2012, the EU finance ministers (Ecofin) decided to lift sanctions on Hungary, imposed in March under the excessive deficit procedure. While annulling the penalty, the European Commission stated that Hungary has taken “the necessary steps to reduce the excessive deficit”. On 30 May the Commission decided that the budget deficit of 2.5% of GDP is expected to be maintained in 2012 in Hungary and fall below the 3% of GDP in 2013.

According to the latest forecasts from November, the Hungarian public finance will close the year with the deficit of 2.5% of GDP and the deficit will amount to 2.9% of GDP next year. Public debt will be reduced from the current 78.4% to 76.9% in 2014. Despite these results, the excessive deficit procedure has not been abrogated for Hungary since the Commission has reservations about the methods the Hungarian government uses to reduce the deficit.

On 7 November, the European Commission recommended the abrogation of EDP against Malta whose deficit fell to 2.7% in 2011 and will amount to 2.6% of GDP this year. The procedure is expected to be abrogated within several weeks. Malta’s debt is 72.3% of GDP and, according to forecasts, will remain at this level in the coming years.

Despite the recession, almost all European Union countries consolidate their finances. The exceptions are the states which had a low deficit or a surplus last year. This year and next year they can afford to ease their policy in order to sustain the economic growth.

Poland reduced much of the public finance deficit in 2011, among others by reducing contributions to open pension funds. The deficit will continue to decline this and next year, though at a lower rate. The Polish deficit is higher than the average in the euro area, although significantly lower than in the countries affected by the crisis of public finance (except for Italy).

The Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union, popularly called the fiscal pact, which is to be ratified soon, requires signatories to pursue a balanced budget policy. This means a budget where the annual structural balance of the general government sector is not greater than 0.5%. A higher structural deficit, but not higher than 1% of GDP, is allowed for countries where the public debt is significantly below 60% of GDP and the risks in terms of long-term sustainability of public finances are low.

This year Poland will have a structural deficit of -2.9%, and next year -2.2%. It is higher than the average in the European Union. A lower structural deficit will be observed in 18 EU countries this year and 17 countries next year. Ten of these countries are subject to the excessive deficit procedure. Poland holds a rather distant place in the queue waiting for abrogation of the EDP.

OF