In terms of mortality and economic consequences, COVID-19 is the largest pandemic of the last 100 years. However, in the more distant past, due to lower hygiene standards, lack of medicine and lack of medical knowledge, epidemics were far more common and killed a much larger percentage of the population.

The Black Death, the plague pandemic of the mid-14th century, is the most famous of them all, as it reduced Europe’s population by about a half. The plague returned to Europe quite regularly over the next 300-400 years. Cocoliztli – a mysterious illness that crippled the Aztec Empire – was even more deadly, reducing Mexico’s population by 90% over 3 waves of the pandemic.

These are only some examples, as many other infectious diseases, e.g. cholera, flu, smallpox, typhus, yellow fever, and malaria, also spread through the medieval, early-modern and 19th century populations. In this context, it seems interesting to study how these epidemics affected economic activity. In particular, I am interested in their effects on average income, i.e. GDP per capita.

What does theory say?

From a theoretical viewpoint, past pandemics could have either a positive or negative impact on GDP per capita. In a Malthusian economy, that is before the Industrial Revolution, output depends on the amount of land and labour input. As a result of an epidemic, the population shrinks and the amount of land per person rises, which translates into higher income per person.

A similar pattern is also present in a more modern economy, in which output depends on technology, capital and labour. As the population shrinks, capital per worker goes up, and thus income per person increases as well. Such a far-reaching event as a pandemic might also influence technological progress, accelerating the previously existing processes and generating novel innovative ideas.

However, as we have seen over the past year, pandemics might also have a negative impact on the economy, especially when governments impose restrictions on economic and social activity aimed at containing the spread of the disease. Even though restrictions of the current scope and severity have never been seen before, closing infected towns was already common practice in the 17th and 18th centuries, and in some cases, quarantines were also imposed in earlier times.

However, pandemics may negatively affect economic activity even when they are not accompanied by restrictions. Consumers and entrepreneurs worry about their health and their future, limiting social contacts, consumption and investment. These fears and worries might persist even after the epidemic recedes, if economic agents take into account that a similar event might happen again.

Data and research method

Since the conclusions from the theoretical analysis are not clear, the effects of pandemics on GDP per capita must be investigated empirically. I describe the results of such an investigation in the paper GDP Effects of Pandemics: A Historical Perspective.

I began the research by compiling annual data on pandemic death rates for 33 countries from various regions of the world over the period of 1252-2016. Subsequently, I linked it to GDP per capita data from the Maddison Project Database, which gathers estimates prepared by economic historians from all over the world.

If pandemics did not depend on other factors, the data mentioned above would be sufficient to study the impact of pandemics on GDP per capita. However, historical evidence indicates that pandemics often coincide with wars, e.g. epidemics decimated the population of Germany during the Thirty Years’ War, while the Spanish flu pandemic broke out at the end of World War I. This happens because war damage and large concentrations and movements of troops facilitate the outbreak and spread of disease. Weather conditions are another factor that may affect the outbreak and spread of pandemics – for instance, long periods of drought may weaken people’s immunity to diseases.

In order to control for these potential relationships, I also gathered annual data on armed conflict incidence, while weather conditions are proxied with the data on annual tree ring growth. The inclusion of these additional variables in the model makes it possible to identify a causal relationship between pandemics and GDP per capita.

I estimate the model using the so-called local projections. Local projections is one of the methods that facilitate the calculation of impulse response functions, which describe the impact of a given event (in this case, a pandemic) on a dependent variable (here GDP per capita) in the subsequent periods following the event.

In this way I can distinguish the short-run effects of pandemics on average income from their medium-run and long-run impact. Compared to other methods that facilitate the calculation of impulse response functions, such as vector autoregression (VAR), local projections are more flexible (it is easier to adjust the model specification), more robust to specification errors and easier to implement in a panel data setting.

Baseline results and conclusions

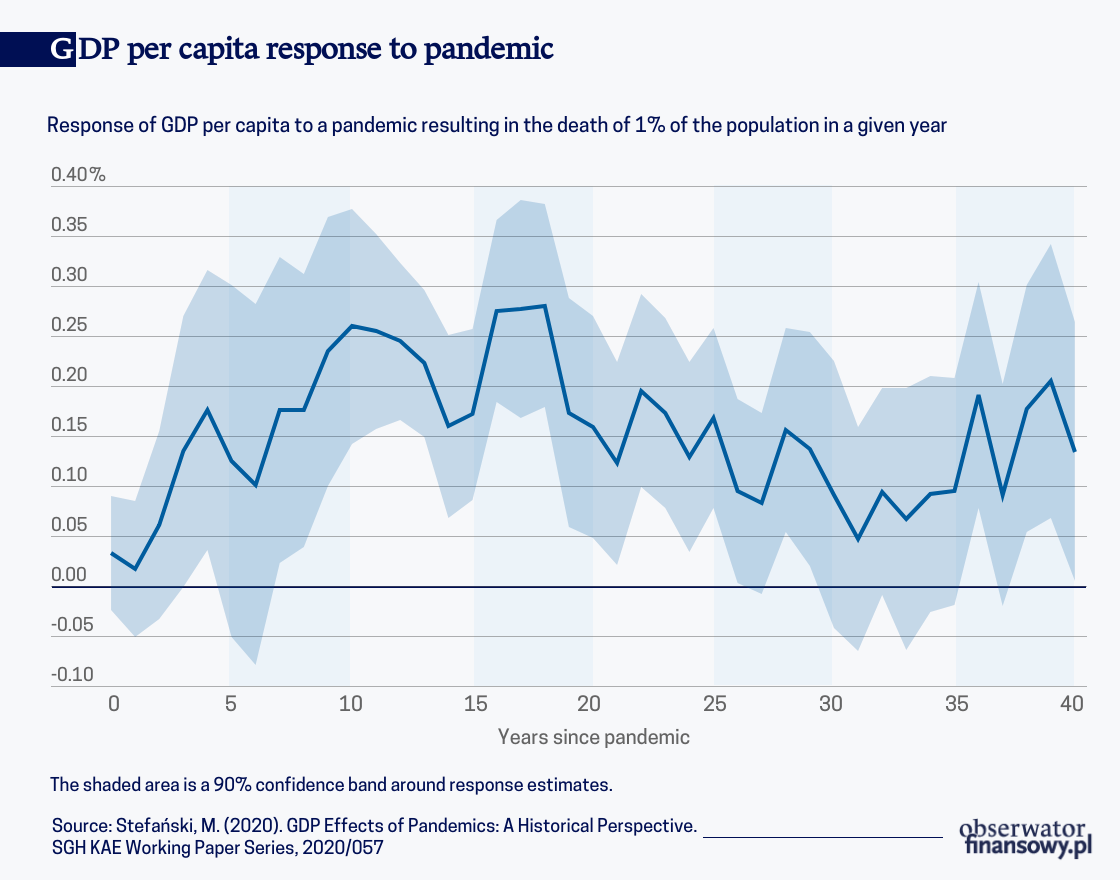

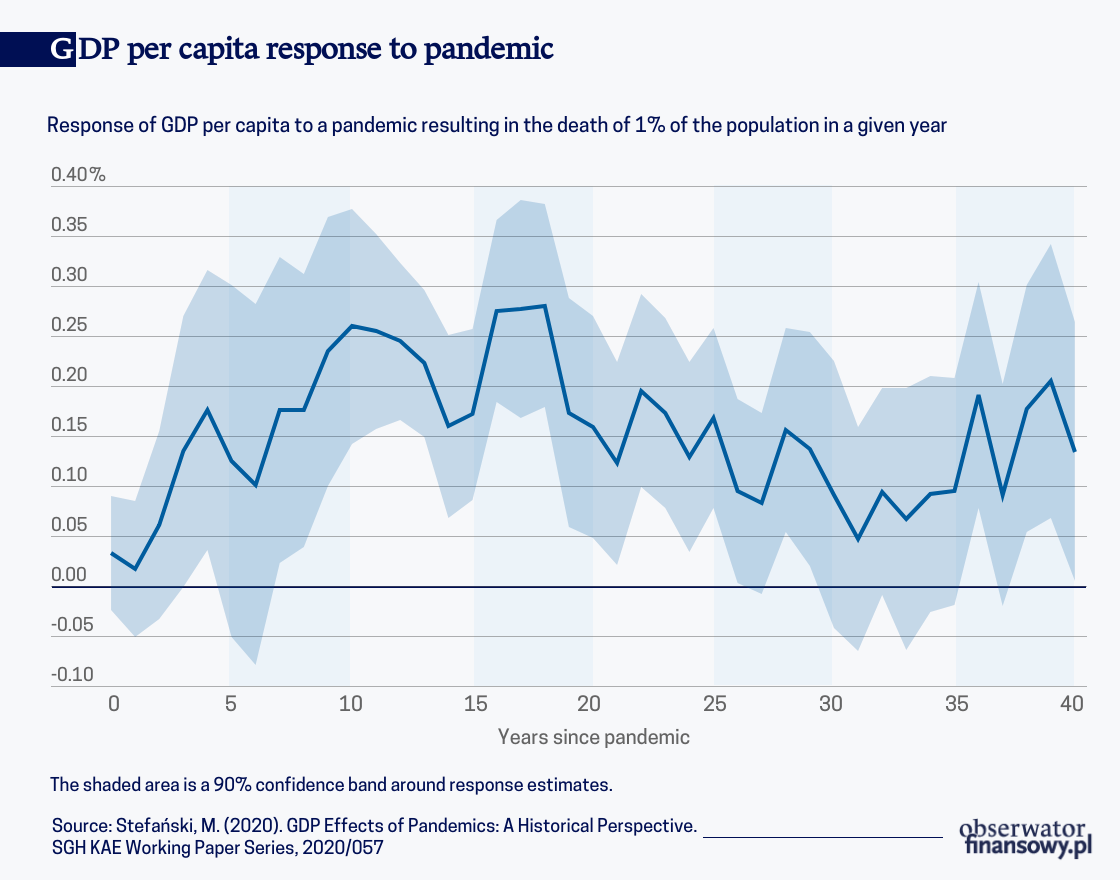

The results indicate that initially, pandemics have a neutral impact on GDP per capita. However, in subsequent years income per person begins to rise, and after 10 years a pandemic resulting in the death of 1% of the population increases GDP per capita by over 0.2%. This impact peaks after 17-18 years, when income per person is almost 0.3% higher compared to the scenario in which the pandemic did not take place. Over the next years the impact of the pandemic wanes somewhat, but remains statistically significant even after 40 years.

Therefore, in the short run factors affecting GDP per capita seem to roughly balance each other out. Later on, the negative factors, related to restrictions and other disruptions, higher uncertainty and lower expectations about future economic activity, fade away, while the positive effects related to the rise in capital per worker begin to dominate. These capital-related effects also start to wane at some point, but they are replaced by other factors, probably related to institutional changes and technological progress, which sustain the positive effects of pandemics in the longer run.

This basic pattern of results – a neutral impact in the short run and positive after 10-20 years – remains intact independent of the model specification. However, the impact of pandemics on GDP per capita is somewhat larger, but fades away in the long run, when only small and mid-sized pandemics, non-European countries, or the effects of pandemic incidence (their scale not being considered) are studied.

The results and the COVID-19 pandemic

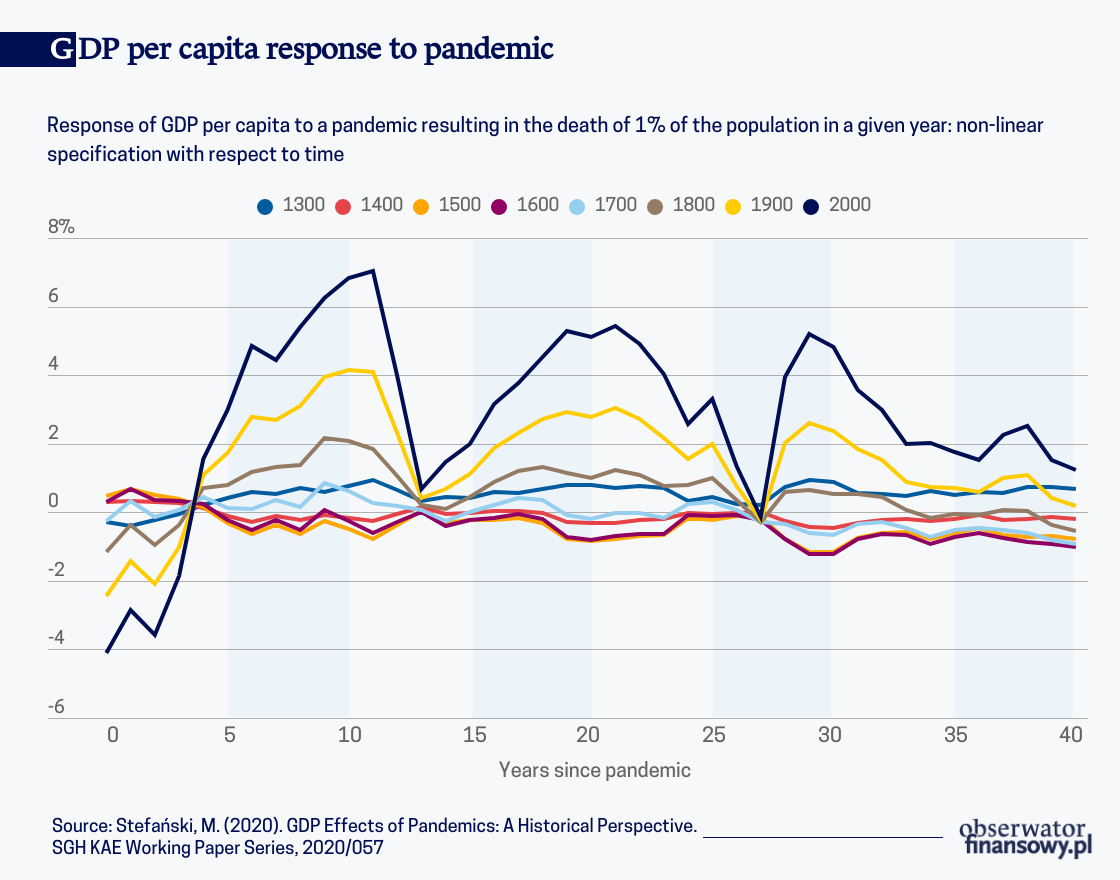

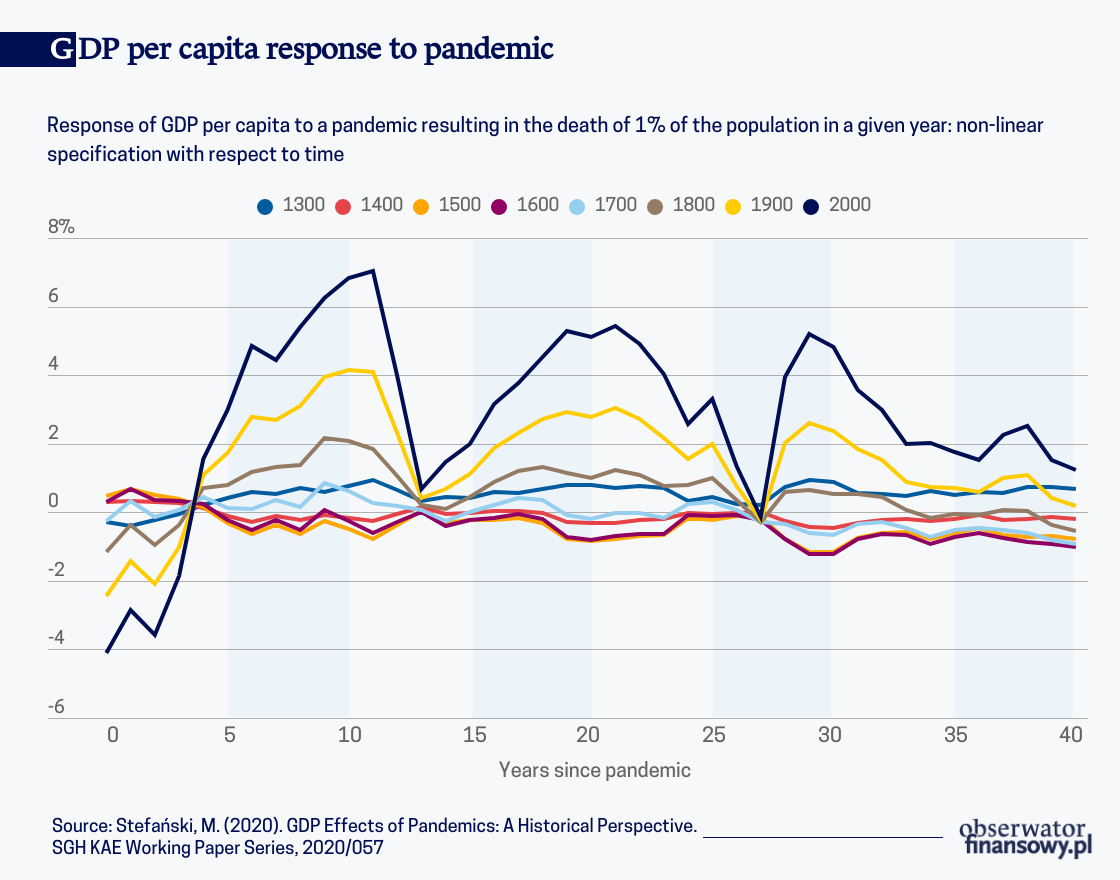

The results of the study cannot be directly used to forecast the effects of the coronavirus pandemic – the differences with previous pandemics in terms of economic structure, medical knowledge, and government actions are way too large. Having said that, when the model specification allows for pandemics breaking out at different times to have a different impact on income, the positive impact of pandemics does not wane in later years. On the contrary, the medium-run and longer-run effects even increase, while the short-run impact turns negative, as we would expect.

Even though these results might not be excessively reliable due to a low number and a small scale of post-World War II pandemics, they might regarded as a source of optimism that the long-run consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic will not be as negative as initially envisaged.

The data from the described study is available here: Stefański, M. (2020). GDP Effects of Pandemics: A Historical Perspective. SGH KAE Working Paper Series, 2020/057.

The views expressed in this article are the private views of the author and are not an expression of the official position of the NBP.