There are several explanations for their change of mind, yet it seems that the greatest influence on their decision had the improvement of the Hungarian economy since the global financial crisis. Hungary’s economy then suffered tremendously as a result of heightened risk aversion and the suspension of inflow of foreign capital, forcing the Hungarian government to apply for financial assistance to the IMF and the European Union.

Capital changes direction

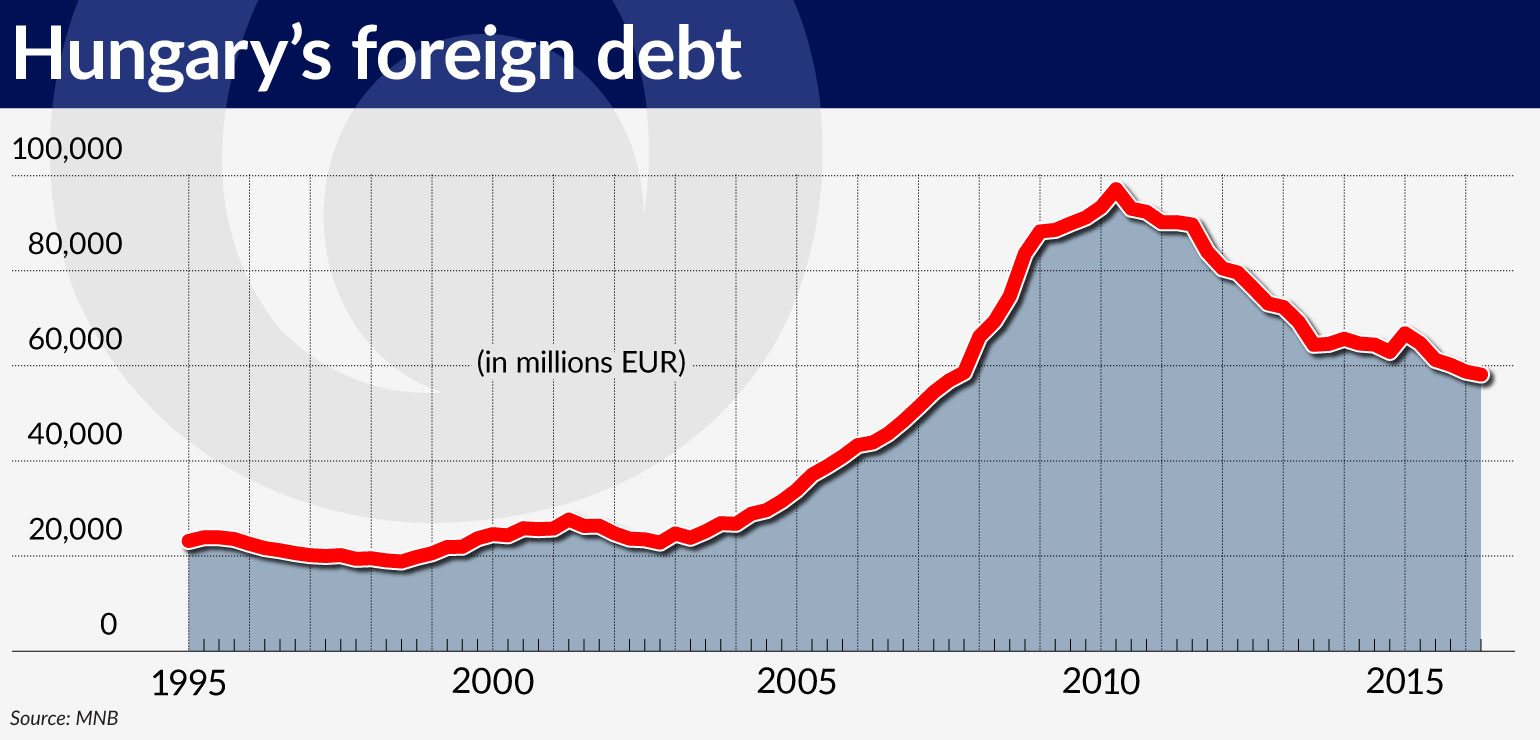

Until 2009, Hungary, like other Central and Eastern European countries, had struggled with the issue of a wide current account deficit. It was financed with the inflow of foreign capital, which led to an increase of foreign debt and economic growth becoming dependent on the global economic outlook. In recent years, however, things have evidently picked up. Not only the deficit vanished but a large and relatively stable surplus has appeared, mostly on the back of the improving trade balance.

At the same time, Hungary has turned from a borrower into a provider of net capital to global markets which has led to a clear reduction of the country’s foreign debt and reduced the vulnerability of the economy to potential global shocks and currency fluctuations. Foreign debt was reduced in the public sector, where the share of non-residents holding Treasury bonds has clearly fallen in recent years. The foreign debt of enterprises and financial institutions has also shrunk markedly.

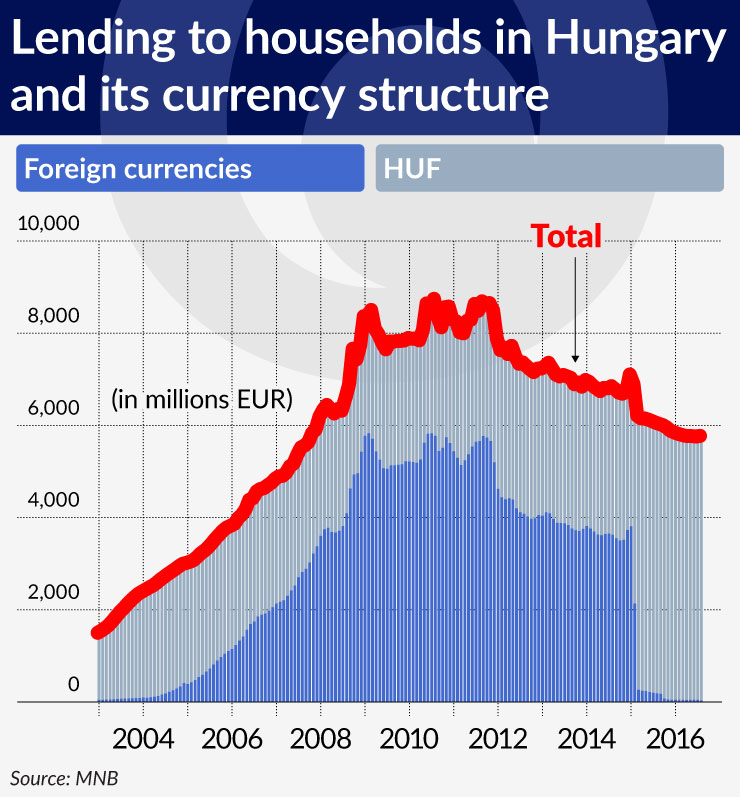

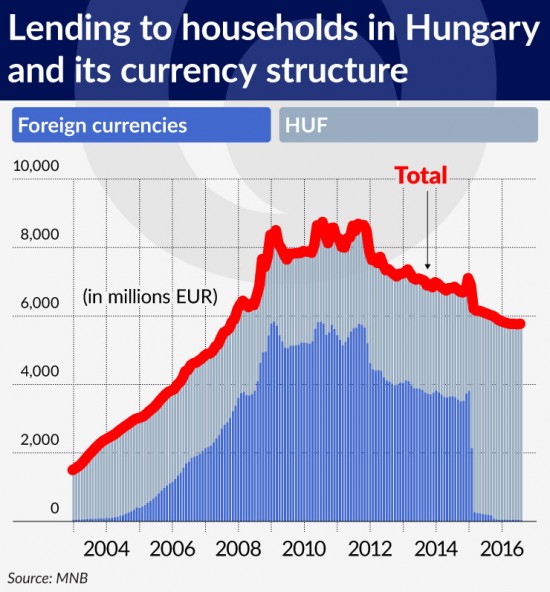

Another important factor contributing to Hungary’s improved credibility among foreign investors is the elimination of the issue of foreign currency denominated loans for households thus individual customers are also no longer exposed to currency fluctuations.

The first steps in this direction were taken in 2012, and the conversion plan was ultimately completed in 2015. The conversion plan also provided for compensation to households for the charges collected with respect to excessive FX differences and interest rates on loans. As a result, the share of foreign currency lending to households, including mortgage and consumer loans, fell from approx. 70 per cent in 2011 to almost zero by the end of 2015.

(infographics Łukasz Rosocha)

The reduction of the scale of foreign debt and the conversion of foreign currency loans would not have been possible if it had not been for the central bank’s active support of government policy. Following the change in the management board of the National Bank of Hungary in 2013, when Andras Simor was replaced by a close associate of the Hungarian PM Victor Orban, the former minister of national economy, György Matolcsy, the cooperation between the government and the central bank became clearly interlocked. The continuing high demand for government bonds, despite their sell off by foreign investors, is largely due to modifications to the parameters of monetary policy, encouraging domestic banks to invest in these instruments. The conversion of foreign currency loans would not have been possible either if the central bank had not made foreign currencies available to commercial banks.

Not fully effective initiatives for growth

In recent years, the National Bank of Hungary has also taken other measures to boost economic growth, though frequently with unsatisfactory outcomes. The most important of them seems to be the Funding for Growth Scheme (FGS). Under this scheme, launched in April 2013, the central bank offered its funds free of charge to commercial banks which subsequently granted low-interest loans to small and medium-sized enterprises.

The scheme enjoyed great popularity but in the central bank’s view it did not fully achieve its purpose as it became a substitute for other banking products. Therefore, the FGS practically did not induce lending in Hungary at all, so the National Bank of Hungary decided to gradually withdraw from it, substituting it with another program that would help banks obtain funds to develop lending in the market.

Despite Hungary’s economic stabilization and a reduction of various external imbalances, rating agencies keep pointing to numerous risk factors that might disrupt the stability.

One of the major threats to the long-term growth in Hungary signaled by market observers seems to be the rising involvement of the state in the economy in recent years. Although the government and the central bank are gradually backing out of the active policy of support for the economy, the presence of state ownership remains high. This is best seen in the banking sector. The Magyarization (Hungarization) of banks is one of the leading campaign slogans of Victor Orban.

‘Hungarization’ of banks

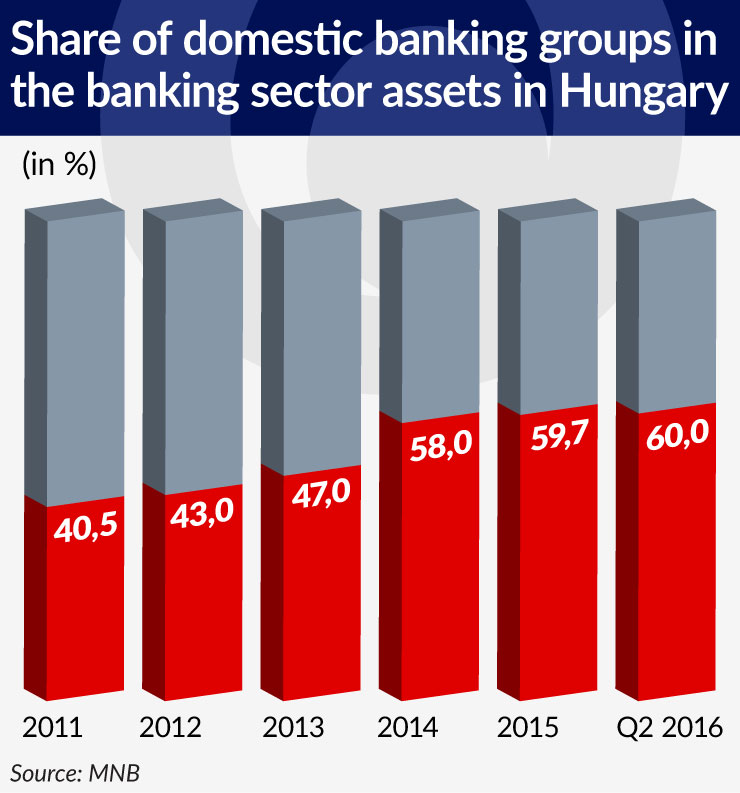

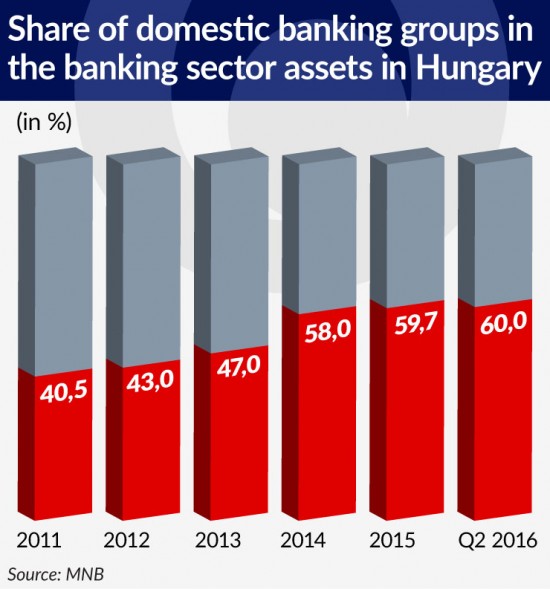

In 2010, Orban promised that half of the banks in Hungary would be placed in Hungarian hands, and he successively pursued this policy by, among others, causing subsequent institutions to be taken over by the State Treasury. In 2013, the government acquired two relatively small banks: the Széchenyi Bank and the Gránit Bank. In the following years, however, it reached for more significant market players. In 2014, it was the MKB (the fifth largest commercial bank in Hungary), in 2015 – the Budapest Bank (the eighth largest bank), and in June 2016 – 15 per cent of shares in the Hungarian branch of the Erste Bank.

After these acquisitions, the share of domestic banks has reached 60 per cent of the total assets of the banking sector, hence the government’s plan has been more than fulfilled. Yet such a great share of state ownership poses a risk of ineffective allocation of funds and, should the institutions get into financial problems, of additional costs to the state budget related to their potential bailout. The situation in Slovenia, where the reckless lending policy of big state-owned banks has resulted in a banking sector crisis continuing since 2009 practically until today, could serve as a warning to Hungary.

(infographics Łukasz Rosocha)

Cool relations with the European Union

Hungary faces another problem: being in an almost permanent conflict with EU leaders. In recent years the European Commission questioned a number of measures proposed by the Hungarian government, including fiscal policies. They ranged from sectoral taxes imposed on energy and telecommunications companies and retail trade in 2010, solutions regarding the world’s highest banking tax rate, to the questioned progressive rates of retail tax (called the food chain inspection fee) and tax on tobacco products, which eventually prompted the government to unify the rates of these levies.

Other charges made by the European Commission concerned prohibited state aid. It challenged, among others, the underpricing of the construction and operation of the nuclear power plant Paks2. It was not the only objection to this investment, regarded as controversial due to Hungary’s long-term dependence on the Russian energy. The European Commission also challenged the tendering procedure of the construction and operation of the power plant. Moreover, the Commission questioned financial incentives for foreign investors. This included the subsidizing of one of the biggest investment projects in Hungary – the construction of the Audi factory in Gyor – by the Hungarian government, although after a two-year-long investigation the EC ruled in favor of Hungary.

It seems that the tense relations between Hungary and the European Commission pose a threat to the extent that any further infringements on European regulations could result in the suspension of payments of EU funds, which has already happened to Hungary in the past. The investment slowdown observed in Hungary at the beginning of 2016 has to a large extent stemmed from the termination of the inflow of funds under the previous financial framework, amid the still very low absorption of funds under the current framework. It reveals that a possible loss of such an important stimulus to growth would be a severe blow to the Hungarian economy.

The author is an economic expert at the Economic Institute of NBP.