Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

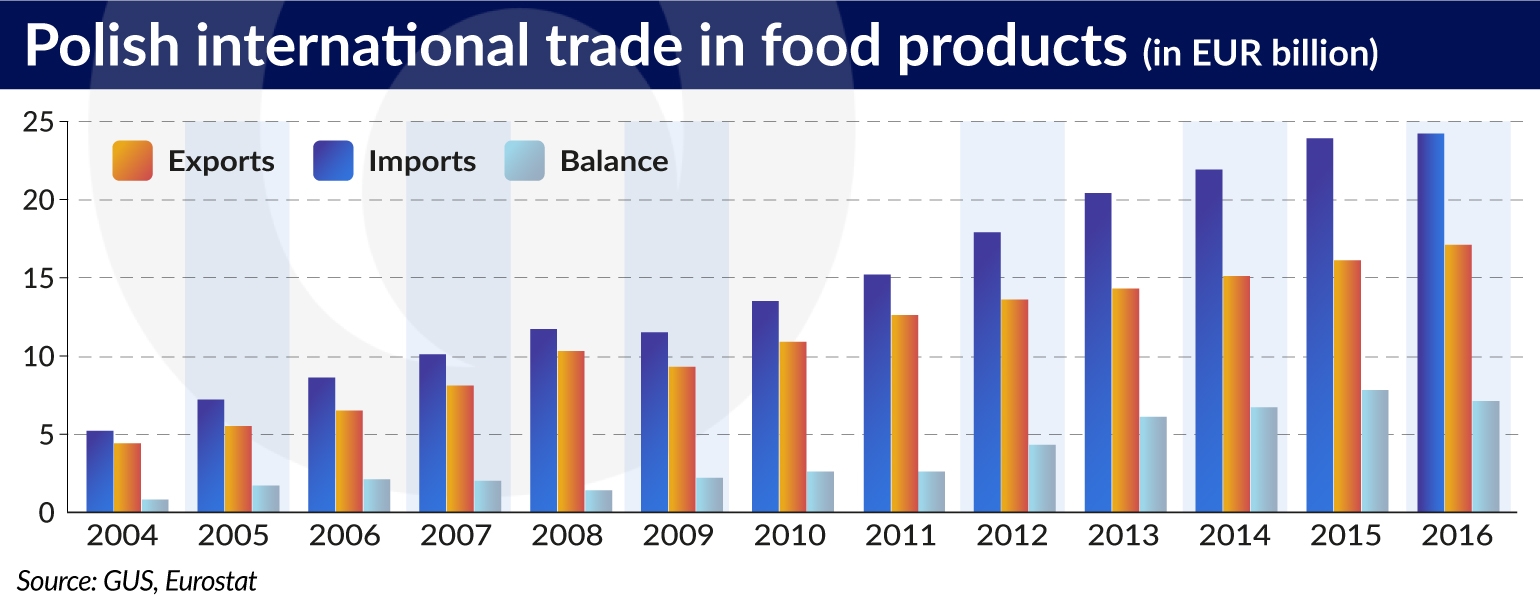

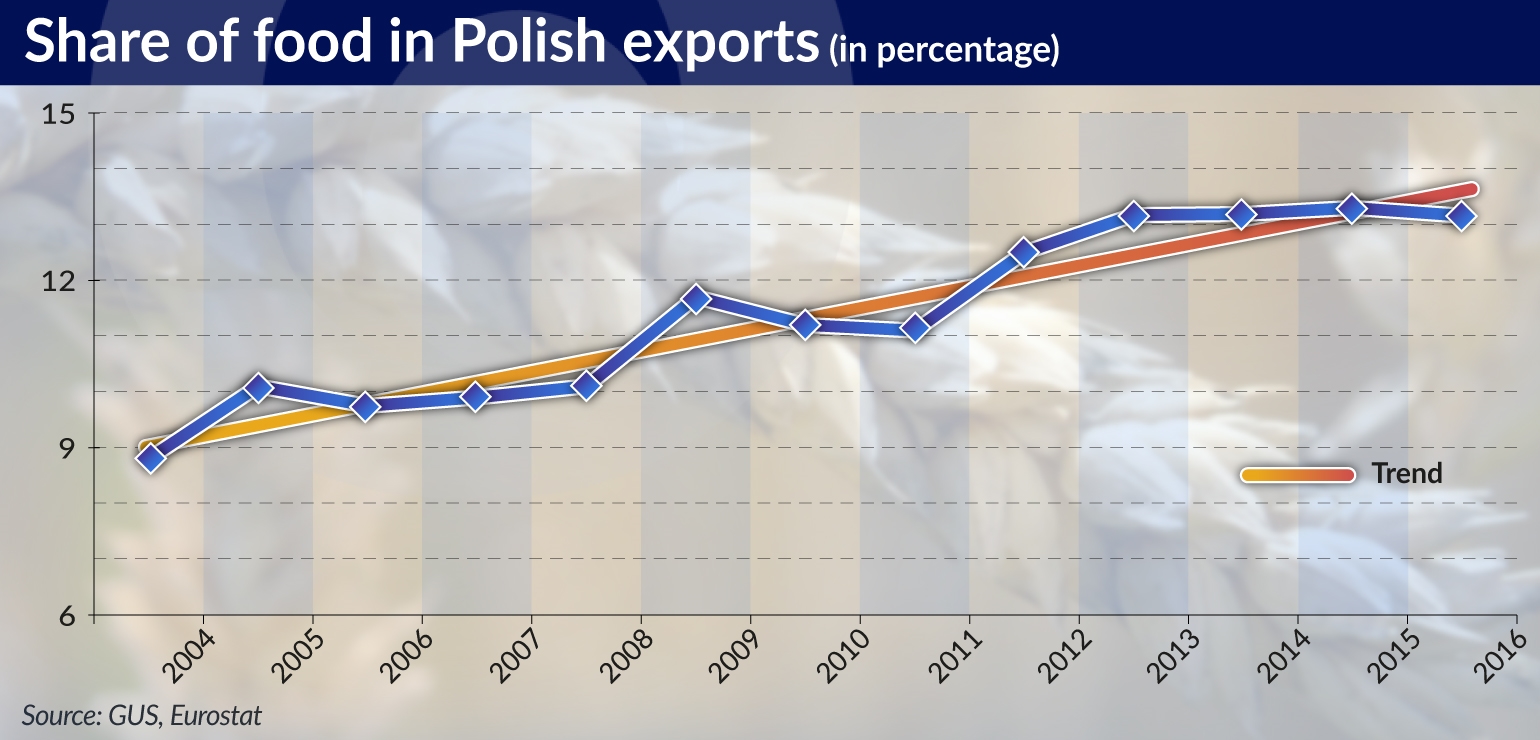

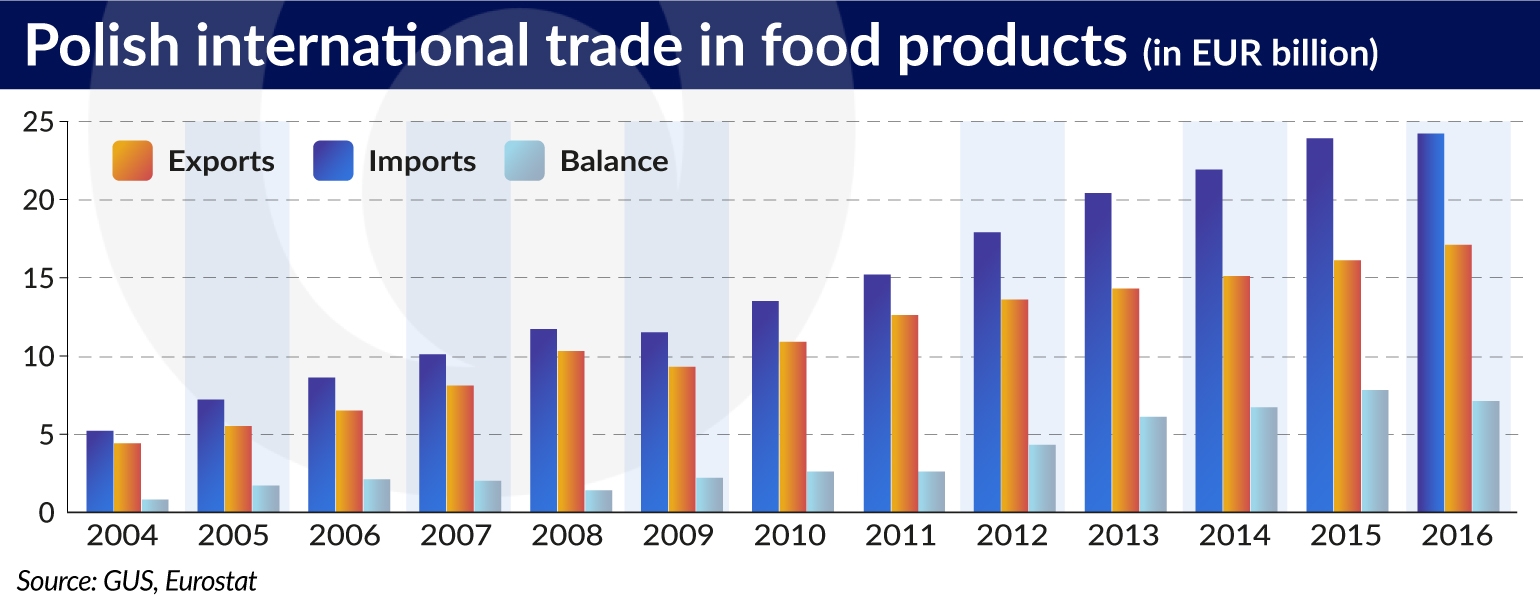

Poland is currently the 8th largest exporter of agricultural food products in the UE (it ranked 11th in 2004). According to the data released by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS), in 2016 the value of Polish food exports reached EUR24.2bn and it exceeded the value of imports by EUR7.1bn. The share of agriculture and food products in Poland’s export structure has continued on an upward trend for years, what indicates Poland’s comparative advantages in food production.

High competitiveness of the Polish agriculture and food industry is also reflected by its numerous international successes. Over the recent years, Poland has become one of the world’s largest exporters of, for example, poultry, champignons, apples and blueberries. Polish export of beef and dairy products as well as re-export of food, e.g. tea, coffee and spices, also experience an intense growth.

Poland’s accession to the EU was one of the key factors behind the success of the Polish agricultural food product export. The flow of EU funds and the necessity to adapt quality to the EU standards have modernized Poland’s agriculture and food industry. Moreover, Polish producers gained free access to the large and wealthy EU market. As a result, EU member states account for approximately 81 percent of Poland’s agriculture and food products export.

The increasing share of Polish food in the EU market faces growing opposition in countries where local producers are unable to successfully compete. Many countries regard the agriculture and food industry as a strategic one in terms of their independence and security; thus, this issue is taking also a political dimension. In consequence, Polish food exporters more and more frequently face protectionist barriers in the EU market. Some protectionist measures are targeted specifically against Polish food, others concern imported food generally.

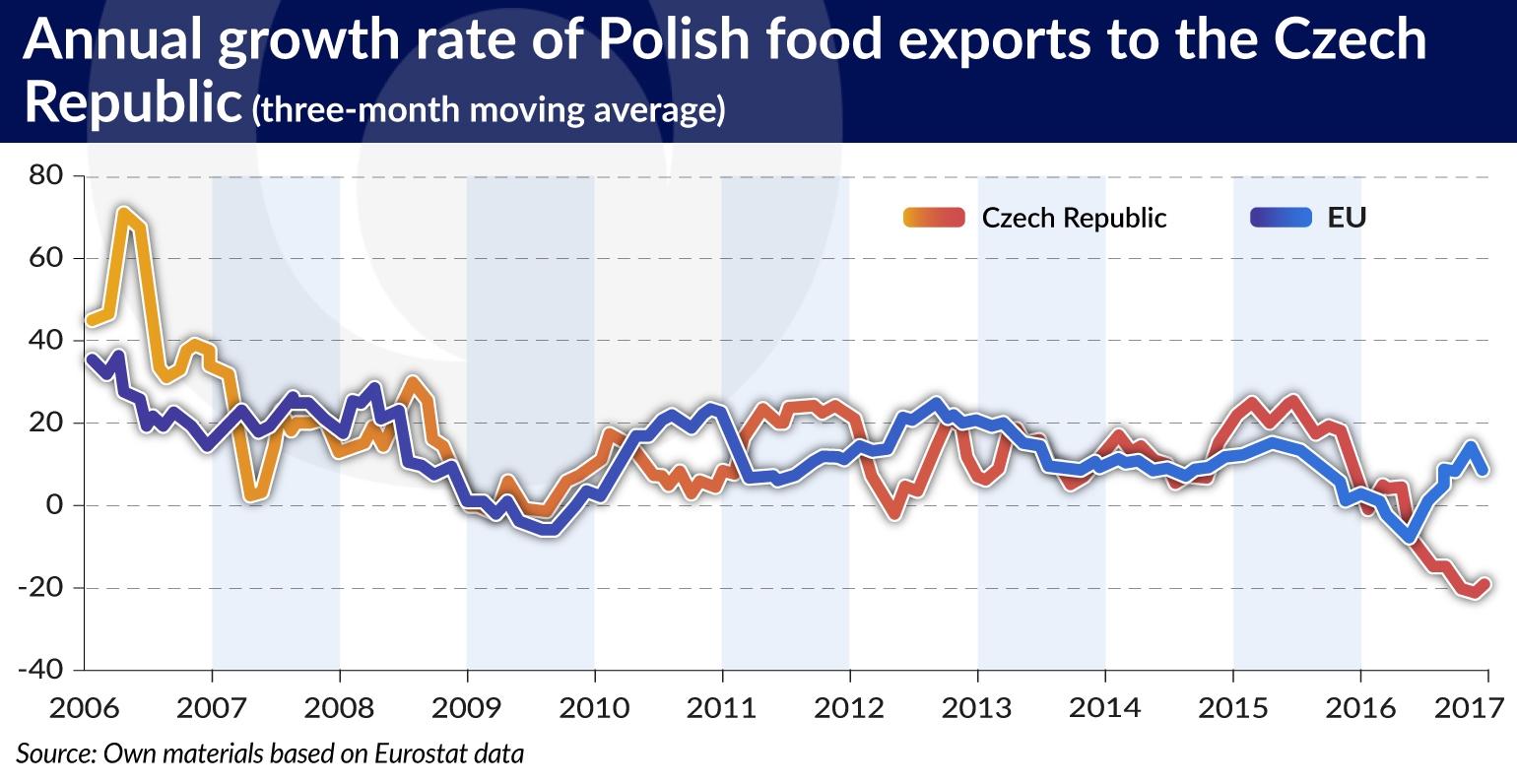

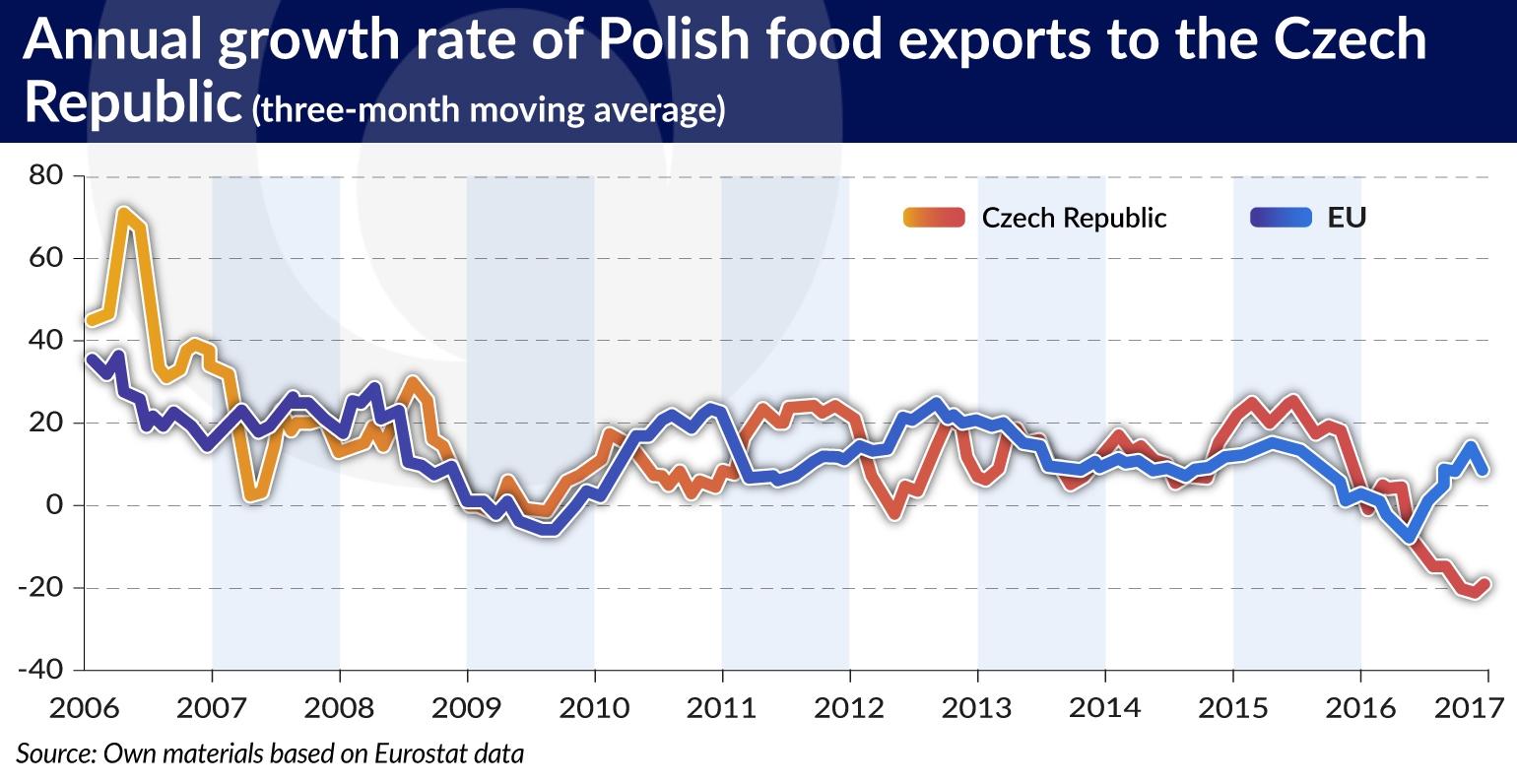

The first group of measures is aimed at discrediting Polish food by questioning its quality and safety without any grounds. This undermines confidence in Polish products that has been built for many years, and which, in the case of food products, is crucial for consumers. Such measures include negative information campaigns concerning Polish food in the Czech Republic and the Czechs questioning credibility of Polish food safety supervision authorities.

The second group of measures is intended to weaken price competitiveness of imported products. These are generally regulations aimed to artificially inflate transaction costs. They involve, among other things, introduction of requirements for additional authorizations and certificates which go beyond EU regulations, obligation to adjust packaging and labels to non-standard requirements, obligation to store documentation in the territory of the country of destination, obligation to inform, in advance, about food transports, including price and weight, and imposition of numerous sanitary controls.

An example of such measures are plans of the Bulgarian government to impose the obligation to sell imported food products in packaging with original information in the Bulgarian language (previously it was enough to attach labels with translation).

The third group of actions is aimed to provide unfair support to the domestic food products and discriminate against imported food. They involve, among other things, the necessity to introduce a certain text on packaging, indicate what percentage of the product was made in particular countries, and also carry out special promotion and introduce special labelling of the domestic products.

The recently introduced Italian law obliges Italian produces of dairy products to provide information on the country of origin of dairy ingredients used in the production process. In turn, Romania has introduced a law obliging large shops to sell at least 51 per cent of food produced by local suppliers.

All these activities violate one of the basic rules of the EU’s common market, that is the free movement of goods. Under this rule, EU member states cannot introduce restrictions to the common trade and are obliged to equally treat both domestic products and products from other EU member states. Despite the fact that the cases of protectionism may be referred to the European Commission, the process of handling complaints takes too long to be an effective line of defense for the aggrieved entrepreneurs who are at risk of losing contracts in a given country and going bankrupt.

The large scale of protectionism, faced by the Polish food exporters in the recent years, is reflected in results of research conducted in 2015 by PwC. According to it over 30 per cent of agricultural and food products exported by Poland to EU member states face discrimination in the form of import barriers. Moreover, on average more than 4 working days are needed to overcome these barriers, and the resulting costs make up approx. 4 per cent of the total export value.

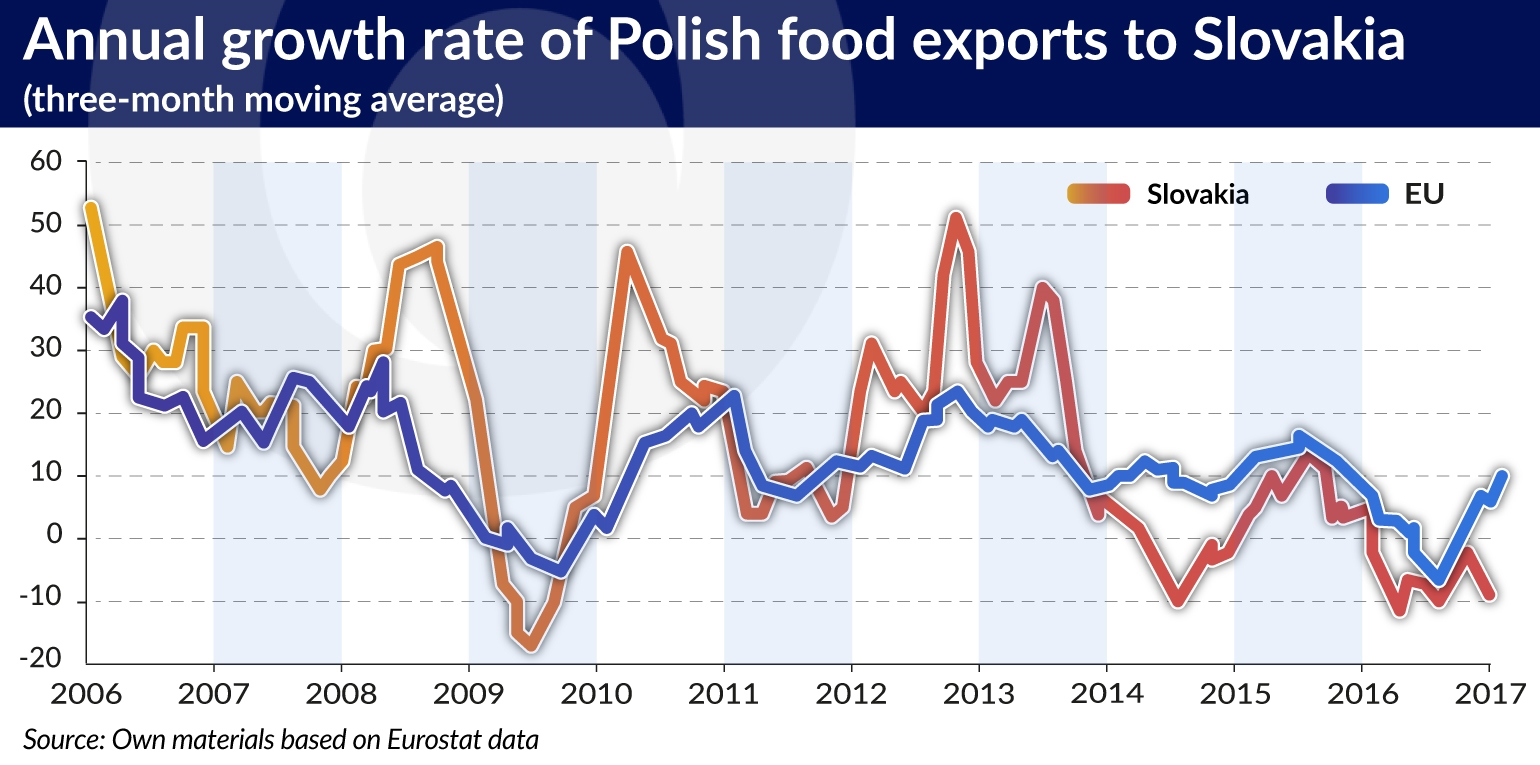

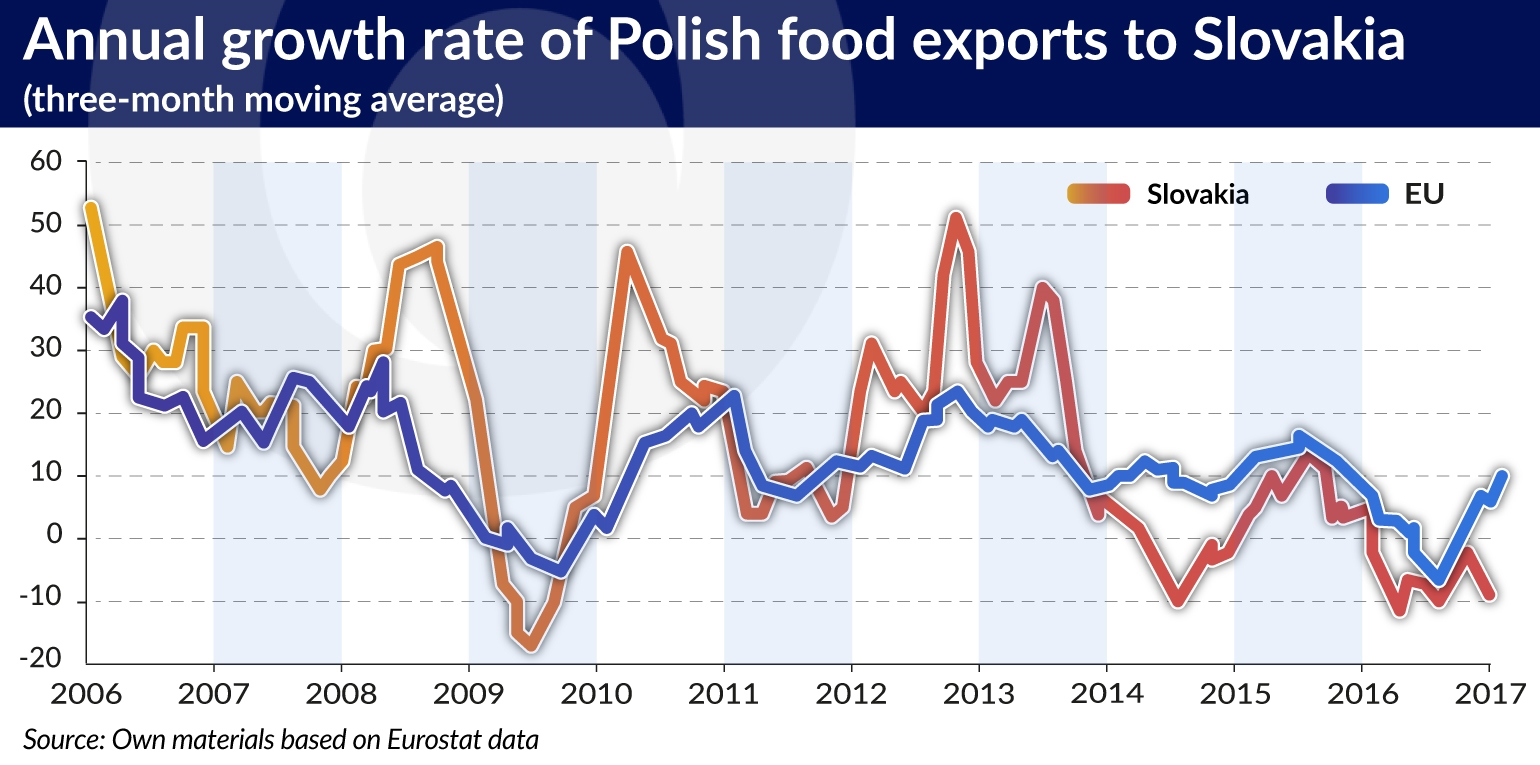

The surveyed companies name the Czech Republic as the first among the countries which apply the most onerous protectionism measures. Other countries indicated by the Polish exporters as applying protectionist practices include Germany, Spain, Great Britain and Slovakia.

For the purpose of the analysis, exports to countries indicated in the PwC’s research as those applying the most onerous protectionist practices were compared with exports to the remaining UE member states. Due to high variability of export data a 3-month moving average was used in the presentation.

The data indicates that in general Polish food producers perform well on the markets where they face protectionist barriers. Agricultural and food products exports to Great Britain in the recent years has been above the average export growth rate to the remaining UE member states. As compared to the EU average, growth rate of Polish export to Great Britain continues at a high level despite unfavorable conditions due to Brexit and the appreciation of the PLN against the GBP.

Moreover, the difference between the growth rate of Polish food exports to Germany and Spain, and the growth rate of exports to the remaining UE member states show an upward trend, indicating that Polish exporters perform better on these markets than other member states. This suggests that very high price competitiveness of Polish food products is still able to compensate the expenses related to protectionist practices.

Different situation is observed in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, where the difference between growth rate of exports to these countries and the growth rate of exports to the remaining UE member states shows a downward trend. Particular attention should be paid to exports to the Czech Republic whose growth, when compared to exports to the remaining EU countries, is at the lowest level since Poland’s accession to the EU.

It may be largely attributed to a significant increase in protectionist practices in that country in 2006, affecting, for example, Polish egg exporters. Last July, during a press conference, the Czech Minister of Agriculture questioned the quality of eggs coming from Poland and accused Polish producers of dumping practices. However, his statement was not supported by any evidence.

Large batches of Polish eggs used to be recalled at that time. It was justified by the Czechs by the absence of the required documents and marking. What is more, after suspicion of salmonella in Polish eggs exported to the Netherlands, the Czech sanitary supervision exploited the situation and decided to destroy 5 million eggs imported from Poland. Last year, Polish tea exports also faced protectionist practices from the Czechs.

In December 2016, the Czech Agriculture and Food Inspection Authority stated that tea supplied by one of the well-established Polish producers was dangerous for health, however this failed to be confirmed in any laboratory tests.

The examples of the Czech Republic and Slovakia indicate that protectionism can be dangerous for the Polish food export. High price competitiveness of Polish agriculture and food products is becoming insufficient to overcome growing institutional barriers encountered in some foreign markets.

Taking into account big importance of EU countries in the geographical structure of Polish export of agricultural food products, the fight against protectionism on the common market is a crucial issue for Poland. Growing protectionism encountered in the EU in the past few years has also revealed low effectiveness of aggrieved exporters in asserting their rights. This calls for a need to find new institutional solutions which would help to settle trade disputes between exporters and EU member states, and prevent the creation of non-tariff barriers in trade within the EU.

Therefore, we should consider the establishment of a dedicated EU institution which would prevent protectionism in the EU countries and efficiently settle any disputes in that area.

60 years after the Treaties of Rome were signed, EU member states need to be reminded about benefits coming from free trade and specialization. Without the free movement of goods, the success of Czech cars in Poland or Polish food in the Czech Republic would not be so spectacular.

We should know that having double standards in trade does not pay. If we want to sell our products in other countries we also should open our borders to the imported goods. Therefore, if we expect no protectionism from our EU trade partners, we should not be tempted to apply it ourselves.

Thus, placing the “Polish product” label on Polish food products is not wrong in itself but in combination with campaigns promoting only Polish products and discriminating against foreign products at the same time, could seriously undermine Poland’s credibility in its struggle for the interests of domestic exporters.

The fact that Polish food export encounters the strongest protectionism in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, namely countries being Poland’s partners in the Visegrad Group, is also surprising. Strengthened mutual cooperation in other economic areas gives hope that its members will attempt to solve this problem.

Jakub Olipra is an Agricultural Market Analyst at Crédit Agricole Bank Polska.