Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

Warsaw Stock Exchange (mik Krakow, CC BY-NC-ND)

However, the failed attempts to find the source of this thesis lead us to the conclusion that this is simply a widely repeated „media fact” and not the result of empirical research.

Formulating such far-reaching assertions with global implications is risky. Firstly, the situation between countries may vary due to their different levels of economic development and the size of their domestic capital markets. Secondly, there are methodological problems in comparing economic indicators and stock market indices.

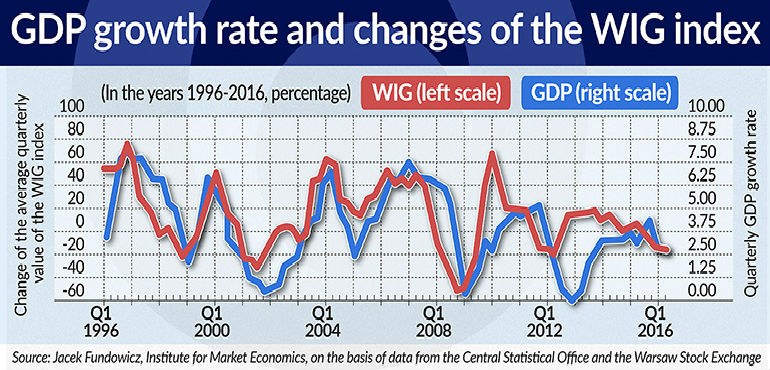

The values of GDP – the measure of economic growth – are obtained for the individual quarters with considerable delay, whereas the changes in stock market indices occur in real time during the trading sessions – although only the closing quotations are usually recorded. The Institute for Market Economics (Instytut Badań nad Gospodarką Rynkową) has developed a method for comparing the stock market situation and the economic situation using the average quarterly rates of change of both variables.

As we can see in the presented chart, the analyzed relationship was quite clear in Poland over the past twenty years, although there were periods when the changes diverged. In the years 1997-1999, 2007-2008 and in the year 2011, declines on the stock market measured with the broad WIG market index came before declines in the GDP growth rate. In the years 2001 and 2005, we saw a simultaneous decrease of the WIG and the GDP growth rate. However, there are no similar examples of changes in GDP being “preceded” by the stock market in cases of upward economic trends. In such situations, both measures usually grow simultaneously.

The lack of a simple and strong relationship between economic growth and the stock market is easy to justify and should not, in fact, come as a surprise. Both the GDP growth, as well as growth on the capital market, are influenced by a number of domestic and international, political and economic factors, and their impact is multidirectional.

A study carried out less than 10 years ago by the Institute for Market Economics, which covered the stock markets and the economies of over a dozen countries, has shown that it is a frequent occurrence for the stock indices to precede the macroeconomic changes by one quarter, although there have also been simultaneous changes in both the stock market and the economy. The studied dependency did not provide clear conclusions for the economy of the United States. The phenomena that have emerged in the global economy in the last 10 years have certainly changed the nature of the analyzed dependence, but likely only to a small extent.

Paul Krugman, the 2008 Nobel Prize winner, presented his opinion on the relationship between the New York Stock Exchange and the American economy in the New York Times. He believes, that the condition of the New York Stock Exchange does not reflect the state of the economy. In saying so, he opposes what he sees as the incorrect belief of Paul Samuelson, another American Nobel Prize winner from 1970, who had previously argued that „stock prices are a measure of the economy as a whole”.

It is worth quoting Krugman’s three arguments justifying the discrepancy between the behavior of the stock market and the economy. The first is a statement that stock prices reflect profits, and not the general revenues. The second is a remark that the share prices depend on the availability or lack of other investment opportunities. The third argument points to the weak connection between the prices of shares and investments in the real economy which lead to economic growth.

It would be difficult to reject Krugman’s first two arguments. Profits obtained on the stock market do not contribute either directly or indirectly to an increase in the income of the population, apart from exceptional situations. It is worth noting that the profits obtained in the stock market do not create added value, or, in other words, are not a part of GDP. In long-lasting booms on the stock market, high realized profits contribute to an improvement in the social sentiment and may influence increased consumption. On the other hand, we should keep in mind that a large part of the shares are usually medium-term and long-term investments and the realization of the profits from the increase in stock prices takes place over many years.

The second argument pointing to the effects of other investment opportunities on the interest of investors in the stock market is equally indisputable. This dependence is easy to observe, for example, in the changes of interest rates by central banks, both in the case of their increase as well as decrease.

Krugman’s third argument about the weak relationship between the prices of shares and investments in the real economy is at the very least debatable. It clearly calls into question one of the main reasons why companies enter stock markets, which is to obtain funds for development, i.e. investments, through the issuance of shares. Financial results are invariably the engine that drives stock prices, and their improvement or maintenance of high-profitability in the conditions of strong competition is not possible without investment.

Krugman argues that the three largest companies of the U.S. stock market (Apple, Google and Microsoft) do not invest in brick and mortar projects, but are instead sitting on piles of cash. This is not a strong argument, because despite their high capitalization, big corporations from the group of Internet technologies represent only a small part of the American economy.

Moreover, Krugman may not have noticed that since 2014 new national accounting rules (SNA 2008) are applied in the global economy, according to which investments in research and development (R&D) are included in capital expenditures. Meanwhile, technology companies are conducting research on a massive scale, which means they are incurring huge financial investments. Changes in the methodology used for national accounts in this regard were largely motivated by the treatment of investments in new technologies as capital expenditures. In the United States, the GDP figures since 1929 have been recalculated according to the new rules. If we were to take another look at the relationship between the stock market situation and the revised economic growth in the United States, it cannot be excluded that the perception of the discussed dependency could be slightly different.

In light of what has been written above, it would make sense to soften Krugman’s criticism of Samuelson with regard to the assertion that share prices reflect the state of the American economy. In the second half of the 20th century the relations between the macroeconomic variables were less complex than in the second decade of the 21st century.

In order to strengthen his arguments, Krugman ironically brings up another quote from Samuelson, that Wall Street indexes have predicted nine of the five recessions that have taken place. The way things are is that the market indices are used in the economic barometers as one of several leading indicators, provided certain formal requirements are met. The economic barometers indicate the possibility of a recession only once this results from the behavior of the majority of leading indicators. Even in such situations, the barometers sometimes send false signals. It is a mistake to predict a recession on the basis of changes in one leading indicator, that is the stock market index. A typical case is the emergence of an economic slowdown when the barometers are indicating the possibility of a recession.

There is no simple answer to the question of whether the stock market is a reflection of the economy. There is no doubt, however, that in many cases, although not always, changes in stock market indices indicate the directions of changes in the macroeconomic trends.

Bohdan Wyżnikiewicz is the deputy President of the Institute for Market Economics