The ongoing debate about the integration of the non-member states with the EU has been based on the neo-classical approach towards economic exchange and integration of separate economies into a single, well-functioning organism. The free market economy and free trade constitute basis of a gradual integration of the peripheries into the EU single market. For the Western Balkans, 6 countries with the most real perspective of the EU membership (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, WB6), these principles have been embedded into the Stabilization and Association Agreements (SAP) and the so-called autonomous trade measures.

These formalities lead the way to increase trade and therefore prepare the WB6 to fully benefit from the EU membership, when their time will come. Also the political connection was developed, which, while officially named as dialogue, has had more of the lecture or guidance character. These resulted in further political pressure to reform economy according to the EU model, enabling further integration with the Union.

For example, “customs duties for all industrial and agricultural products coming from Serbia into the EU (only a few agricultural products were protected by the preferential tariff quotas) were abolished by the EU in 2000”. Furthermore „the reduction of import duties for goods originating in the EU started nine years later, in January 2009, when Serbia voluntarily initiated the implementation of the trade-related part of the Stabilization and Association Agreement, called the Interim Agreement. This agreement introduced asymmetric trade liberalization in favor of Serbia for both industrial and agricultural products”.

Although this agreements look favorable to Serbia, it is worth remembering that in 2000s this country has just finished almost ten years long armed conflict on its territory and abroad. Conflict that lead to international isolation, successful secession of part of its territory and complete dismantling of its production and trade chains. According to the World Bank Serbian GDP in 2000 was three and a half times lower than GDP of smaller Croatia (USD6,5bn and USD21,67bn respectively). In 2000, the EU granted autonomous trade preferences to all the Western Balkans. They will expire at the end of 2020, enabling all the WB6 exports to enter the EU without customs duties or limits on quantities.

Between 2003 and 2019 export to the EU28 increased from EUR4.144bn to EUR24.779bn. At the same time the imports from the EU28 increased from EUR10.151bn to EU32.961bn. That means that the trade deficit also increased from EUR6bn to EUR8bn. Between 2003 and 2019 the deficit has sum up to over EUR120bn. At the same time, intra-regional trade within CEFTA increased “only” from EUR4bn exports and EUR3,9bn imports in 2012, which constituted 23 and 12 per cent of overall turn-out, to EUR5,6bn exports and EUR4,8bn imports in 2018 (18 and 10 per cent respectively).

To compare, for the period 2007-2020, i.e. covering two EU financial frameworks, the EU has allocated EUR8.198bn for all the six countries plus EUR4.117bn devoted to the multi-beneficiary program, which included also Turkey, Iceland (2011-13) and Croatia (2007-13). Allocation of these funds does not mean their efficient spending. Some of them has been misallocated, some simply stolen and some “redistributed” back to the EU.

There is also an ad hoc assistance of the EU. Most recent program has been devoted to fight negative consequences of COVID-19. From EUR3.3bn, only EUR38mln was allocated to immediate support of the health sector, EUR455mln as reactivation package, EUR389mln in assistance funds for the social and economic recovery, EUR750mln of macro-financial assistance, and EUR1.7bn of preferential loans by the European Investment Bank. Therefore, it is highly unclear how many of these funds actually end up in pockets of the WB6 entrepreneurs, hospitals or social services.

The WB6 don’t have much choice as the EU is their main trading partner (around 70 per cent of the region total trade) and the largest investor (over 70 per cent). “Between 75-90 per cent of the WB6 banking systems are foreign-owned (mainly by German, Italian, French, Austrian, and Greek banks). Almost all Western Balkan countries have adopted a fixed exchange-rate regime, linking their currencies either formally or de facto to the EUR, or are using the EUR (as in Kosovo and Montenegro). However, close economic ties with the EU have not helped to modernize the economy or to support the Western Balkans’ capacity to accelerate development. “Despite its proximity to the EU, the region remains a long way from achieving stability and prosperity, and from firmly embarking on the road to successful European integration”, says Matteo Bonomi from the think-tank Istituto Affari Internazionali (the Institute of Foreign Affairs). Majority of the available working force in the region migrated to the EU, mainly to Germany and Austria, but also to some new member states, like Croatia or Slovenia.

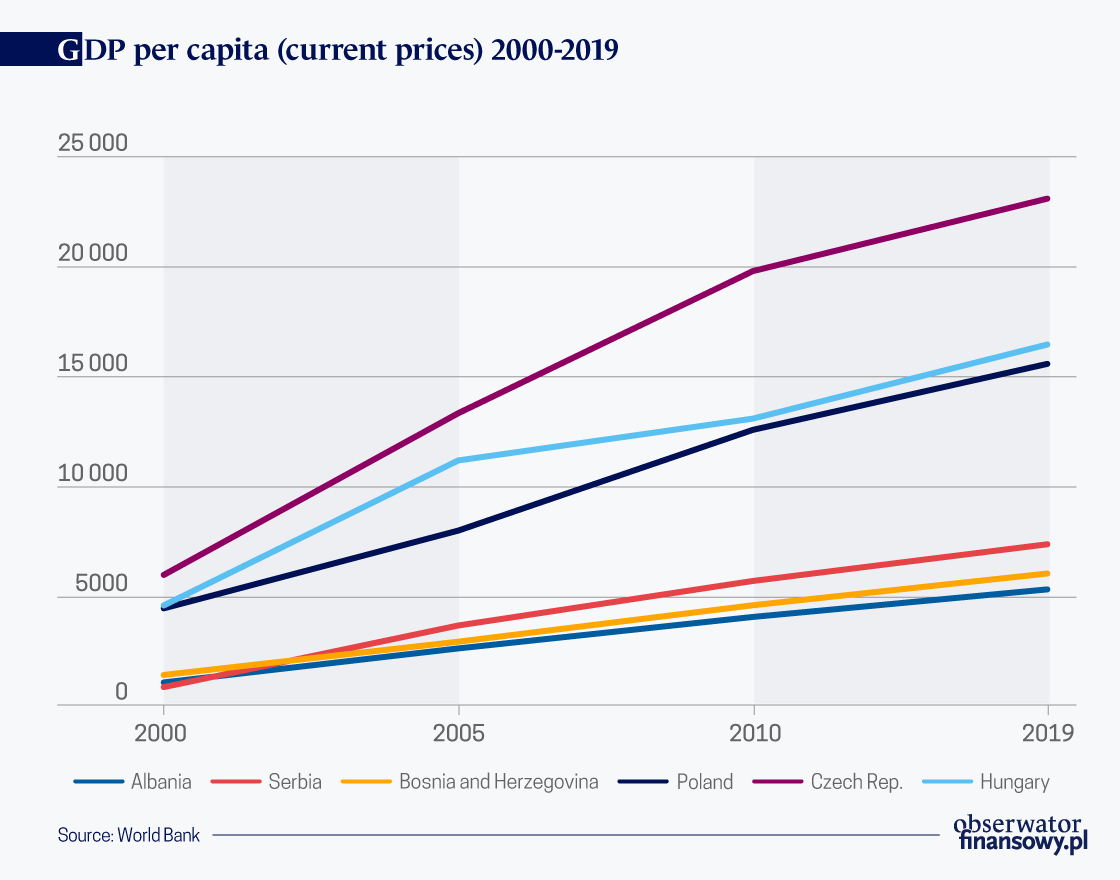

Due to geography (WB6 is surrounded by the EU countries), the WB6 is fated to be closely attached to the European core, yet despite introduction of the model of cooperation that worked for Poland, Czech Republic or Hungary, it does bring expected benefits. The level of life, as well as functioning of the state administrations and public services leaves much to be desired.

„Whereas in Central Europe, rapid market opening, liberalization, privatization, and integration with the EU has favored the arrival of foreign investors, the transfer of capital, know-how, and modern technologies, thereby also facilitating re-industrialization and some economic convergence with the more developed parts of Europe, most Western Balkan countries have experienced a process of continuous deindustrialization, large external account imbalances, high unemployment, falling living standards, rising inequality, and greater risk of poverty and social exclusion,” notes Mr. Bonomi.

According to the World Bank statistics between 2000 and 2019 Serbian GDP (Serbia is the largest economy of WB6) increased from USD6.876bn to USD51.409bn. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the second largest market, it increased from USD5.506bn to USD20.048bn, in Albania from USD3.48bn to USD15.278bn. The development is significant, yet when comparing GDP achieved by Central Europe the gap is still big. In 2019, Poland’s GDP was USD592bn, over ten times more than Serbian. The Czech Republic’s GDP was USD246bn and Hungarian USD160bn.

Despite liberalization of trade and macro-economic policies, the GDP per capita of the WB6 remains on a desperately low level comparing to Central Europe. If the EU wants to preserve its influence and constitute a normative example to the WB6, and therefore to other neighborhoods, it has to readdress the trade policy towards this region. Its meaning for the EU itself although visible, is of little economic value. The region’s share of overall EU trade is only 1.4 per cent. Therefore, the changes would not be harmful to the EU economy nor its finances.

As Bob Milward from the University of Central Lancashire has clarified: “the free trade, as we know it, has not and will not provide mutual benefits to all of its participants”. In his book ”International trade and sustainable development”, Mr. Milward suggests that underdeveloped countries, and so the WB6, when establishing preferential trade agreements between each other are to expect gains that are two and a half time bigger than achieved by a developed economy in a such trade deal. In other words, the EU should further encourage trade within CEFTA.

Instead, the EU expects the WB6 to “do as we say, not as we do”. This inconsistence is characteristic for relations between the center and peripheries. “Trade wars and trade embargos are carried out on a regular basis. Tariff and non-tariff barriers are a commonplace, particularly targeting the export of underdeveloped economies. State-intervention is a major feature of most advanced economies as is corruption and a lack of the so-called democracy. Yet, free trade, free market and “good governance” are the pillars of conditionality contained in the packages of the international financial institutions and the condition attached to preferential trade agreements,” wrote Mr. Milward.

Instead of emphasizing freedom of trade and supremacy of “invisible” market forces, the EU should be bold enough to review its strategy, that has so far promoted its own developed economies integrated around Eurozone and the European Single Market. Alternately, an asymmetric European trade regime towards the WB6 should be introduced. A regime, that would reflect two different principles mentioned by Mr. Milward: unequal treatment for unequal partners and European difference principle. Such a model would be beneficial to the least advantaged European states, and therefore draw WB6 societies substantially closer to the common European project.

Jan Muś works as an analyst in the Balkan Department at the Institute of Central Europe in Lublin