Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

(Infographic Bogusław Rzepczak)

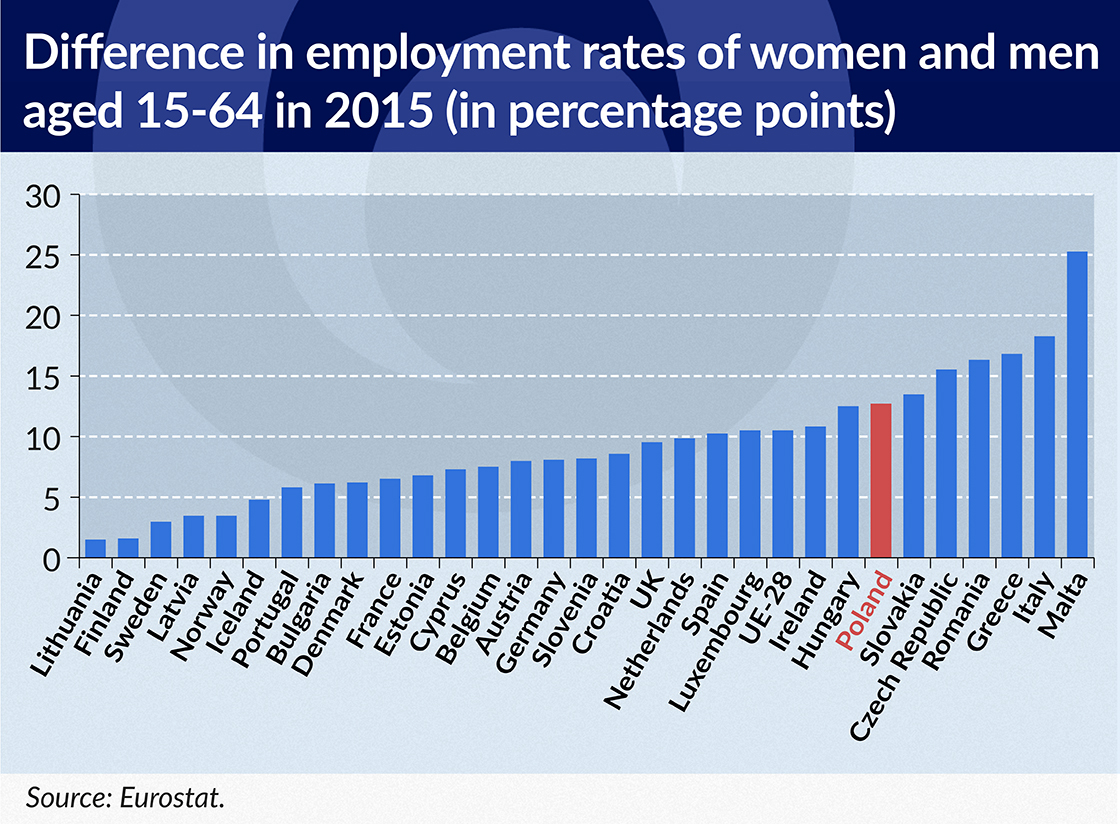

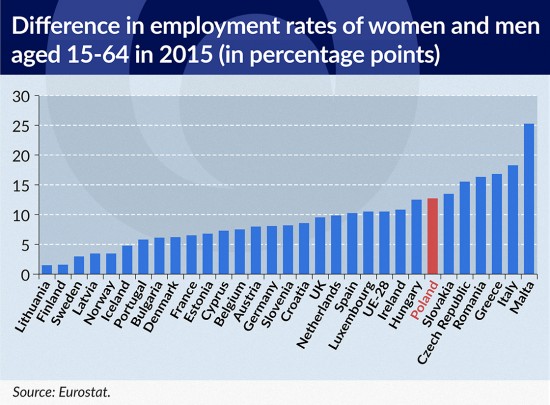

In 2015, the difference between the employment rate of men and women reached 13 percentage points – 69 per cent of men aged 15-64 and less than 57 per cent of women in the same age group were employed.

Where else do such great disparities in employment exist between the sexes? In Slovakia (13 percentage points), the Czech Republic and Romania (16 percentage points each), Greece (17 percentage points), and in Italy – 18 percentage points. The widest disparities are found in Malta, and in Turkey, where it is 40 percentage points.

The average difference in professional activity between the sexes reaches 10 percentage points for the EU countries, but in Lithuania and Finland it is less than 2 percentage points. In Portugal it is only 6 percentage points, and in Spain – 10 percentage points.

Therefore, in terms of differentiation of the activity of women and men, Poland is similar to Spain, Greece and Slovakia. These countries have also historically been more patriarchal and are strongly attached to tradition, which has its advantages, because there is more redistribution within the family, and not through the state.

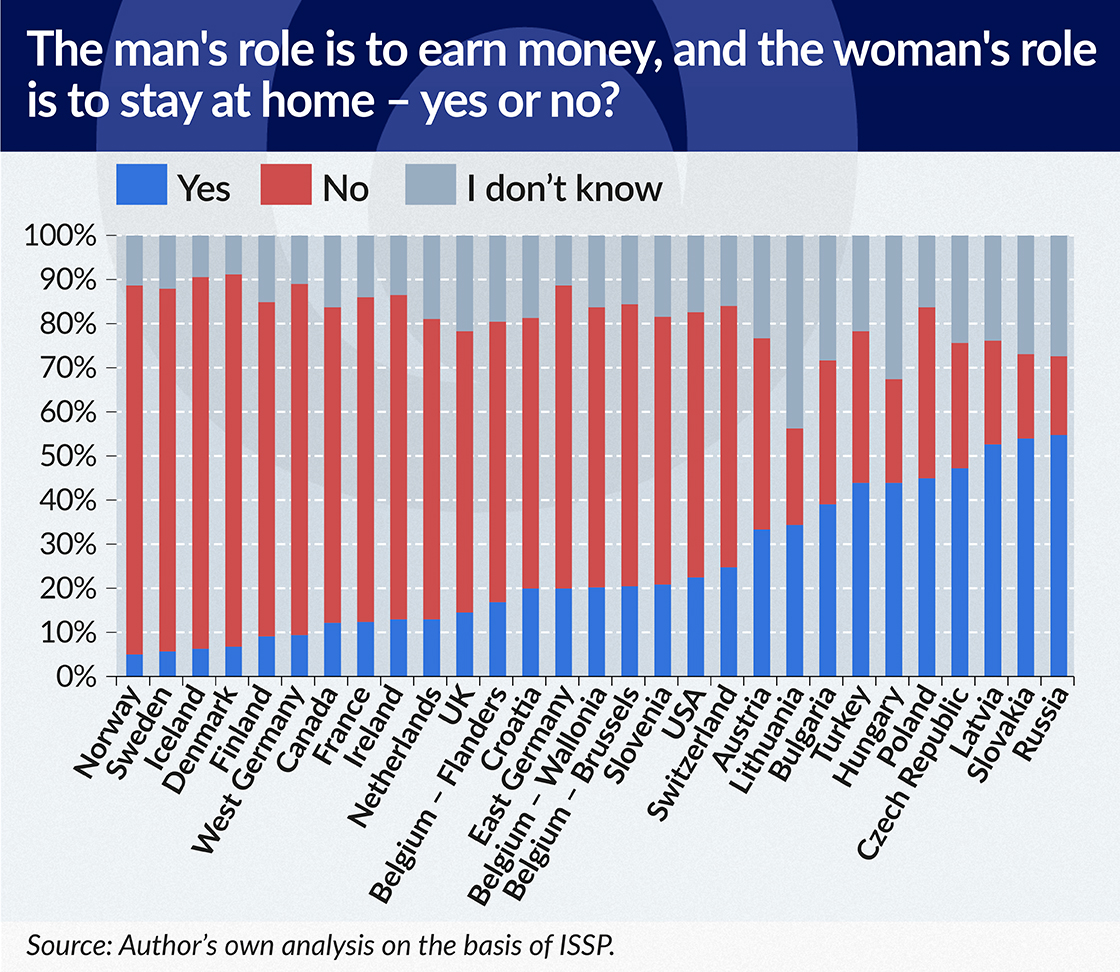

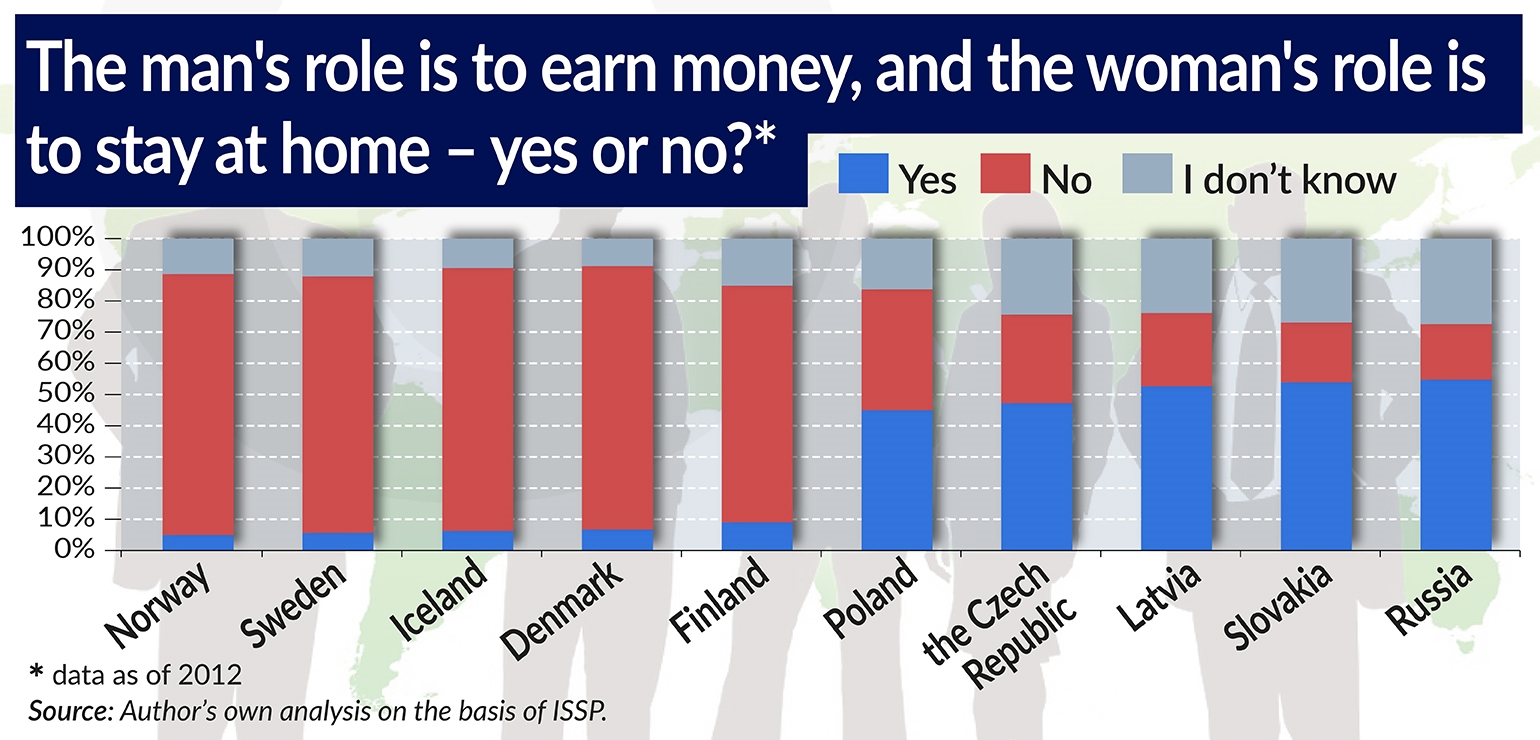

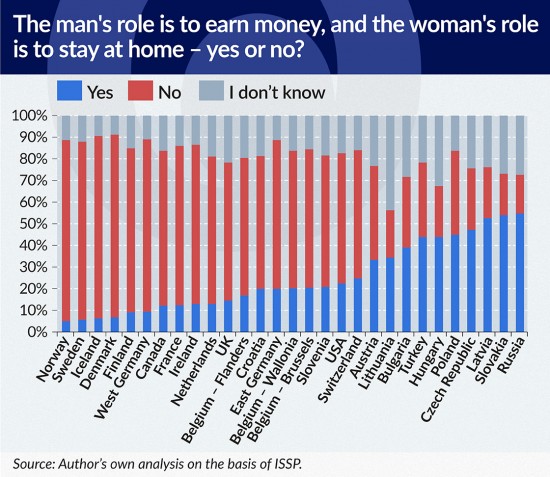

In 2012, Europeans were asked their opinions on female and male roles. Some 45 per cent of Poles agreed with the proposition that the man’s role is to make money, and the woman’s role is to take care of the home, while 40 per cent had the opposing opinion and the rest did not have an opinion. Similar results were recorded in Turkey, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic. In the former German Democratic Republic, only 20 per cent of residents supported the patriarchal economic system. Similarly, in the United States, 20 per cent of respondents support the traditional division of roles between men and women.

In other European countries these percentages are much lower. The European leader in patriarchy is Russia, where more than half of the population believes that the man should earn, and the woman should stay at home.

The attitudes of Poles are changing. As many as 40 per cent believe (which distinguishes Poles from, among others, Hungarians, Czechs, or Turks) that the role of the woman is not only that of a homemaker. It will still take some years before this becomes a majority view, though.

(Infographic Bogusław Rzepczak)

Opinions favoring economic roles for men over women can be a barrier to undertaking employment, even one that allows for combining the roles of mother and employee. Despite years of discussions on making the labor market more flexible and the use of solutions such as teleworking and part-time employment, only civil law contracts have become more widely used. In Poland only one in 10 women (i.e. 705,000 among those employed) has a part-time employment contract. In EU countries, an average of one-third has this type of contract, and among the leaders the figures reach 77 per cent (in the Netherlands) and 60 per cent (in Switzerland). In the United Kingdom 41 per cent of women are employed in this way and in Germany – 47 per cent.

Poland is no different in this respect from the previous reference group, that is, the countries with a traditional patriarchal approach – 7 per cent of Hungarian women, 8 per cent of Slovakian women, 9 per cent of Romanian and Czech women are employed on a part-time basis. In Portugal, Greece and Latvia the figures are all below 20 per cent. The percentage of Polish women employed on a part-time basis has stayed at around 10 per cent for more than 10 years.

It is possible that Polish women do not want to work part-time because their earnings would be too low. This of course stems from the difference in earnings between still-developing Poland and wealthier Western economies (wages in Poland are 39 per cent lower than the average in developed countries, adjusted for purchasing power parity).

In addition, women are a third more likely than men to be employed on the basis of civil-law contracts in the service sector, catering industry and the hospitality industry, where such forms of employment are popular. This, however, limits their rights, especially in the context of dismissal rules and the leave entitlement. Parental benefits are available to those with permanent contracts.

Many Polish women do not work after childbirth (>>More ). In Poland, 54 per cent of women with a child aged up to 2 years are employed. In France this figure reaches 61 per cent, in Russia 71 per cent, and in the Netherlands and Denmark it exceeds 75 per cent. Much lower figures are found in the Czech Republic (20 per cent), in Slovakia (15 per cent) and

After rearing their children, some Polish mothers return to the labor market (65 per cent of women with children aged 3-5 years). This is, however, a much lower level than in the case of the leaders: 70 per cent of Czech women, 74 per cent of French women and four-fifths of Dutch, Finnish, Estonian, Danish, Slovakian and Russian women who have children of this age, are employed.

The reason for the lower professional activity is the lack of support in child-rearing. The results of an analysis by the CBOS (Public Opinion Research Centre) shows that among women who could count on the support of their parents, the likelihood of deciding on another child is more than three times higher than among those who cannot expect such support. The attitude of the partner is also important in the context of further reproductive life plans – a woman who could count on a partner’s involvement in child care is almost three times more likely to decide to have more children.

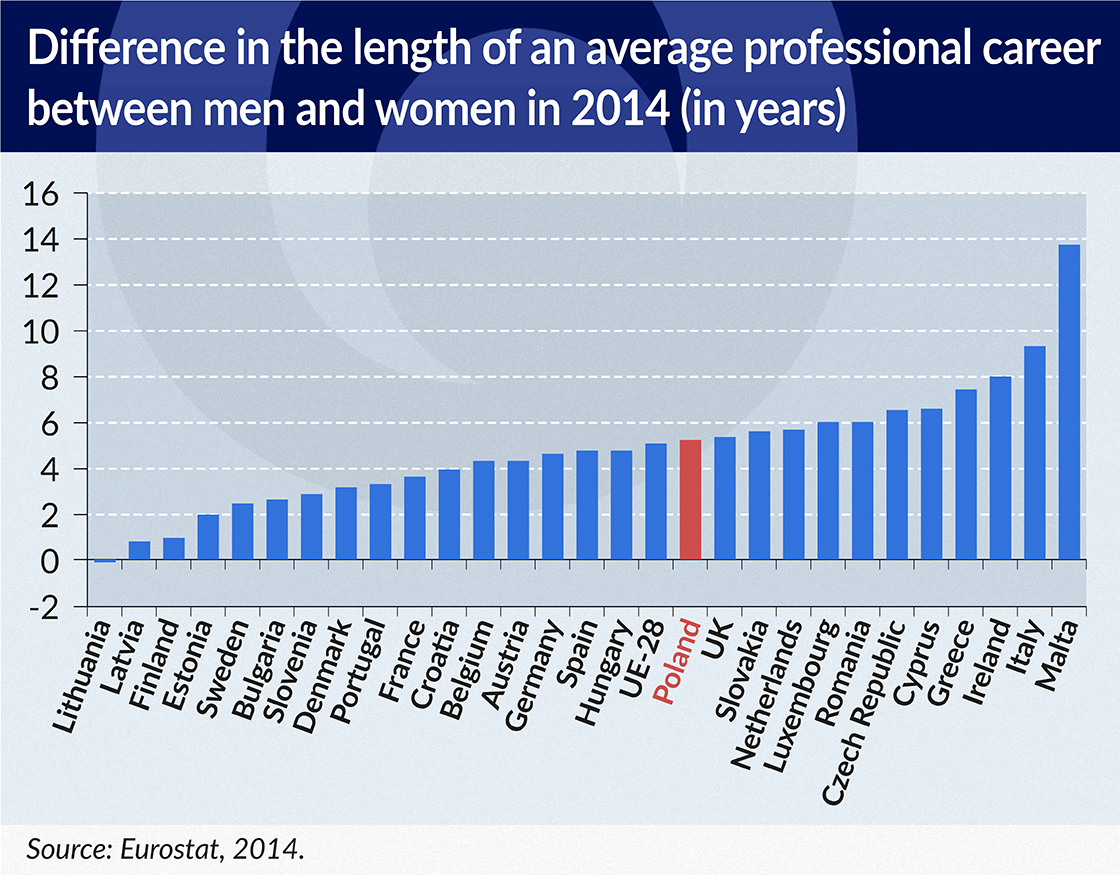

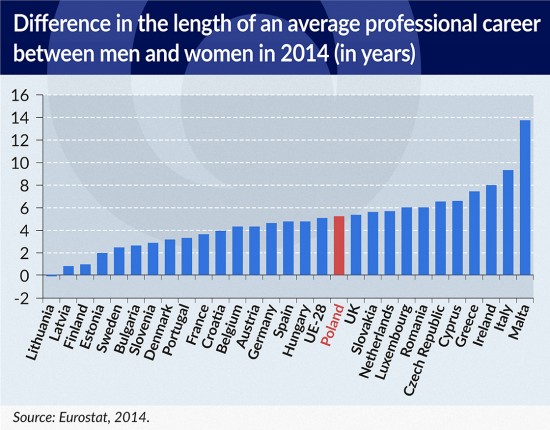

In 2014, Polish women had a working life before retirement that was 5.2 years shorter than for men. This means that over their lifetimes, women worked less than 30 years and men about 35 years, on average. These differences are caused by breaks for raising children (once without, and today with paid parental leave), and by the possibility of early exit from the labor market. The retirement age for women is lower and will remain at 61 years until the end of 2016.

In the past there was also a possibility for women to retire at the age of 55, and many took this opportunity. Currently in the EU, the average difference in the length of a professional career between women and men is about the same as in Poland – 5.1 years. These differences are greater in the countries of the South – in Malta it is 13.7, in Italy 9.3, in Greece 7.4, and in Cyprus – 6.6 years. Lithuania is the only country where women work 0.1 years longer than men.

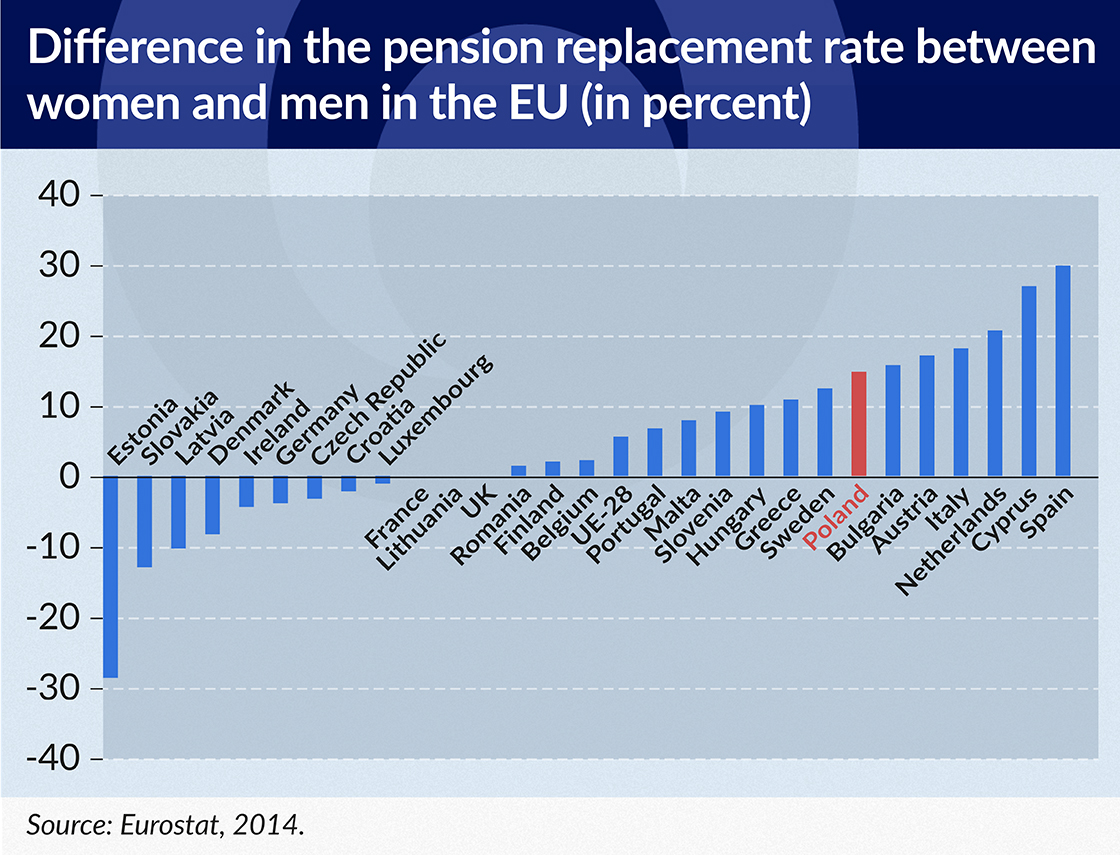

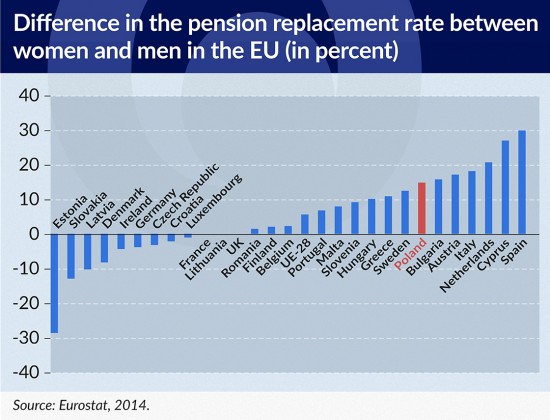

The length of professional career and remuneration – which is lower because women often work in different capacities and in different sectors than men – affect pensions, which tend to be lower. The average pension for women is about 61 per cent of pre-retirement salaries (calculated as the proportion of the benefits paid to pensioners aged 65-75 in relation to the earnings of working people aged 55-65). Men’s pensions are 70 per cent of their last earnings.

The difference between the pensions paid to men and women is 15 per cent in Poland, one of the largest gaps in the European Union. On average in Europe, men receive 5 per cent higher benefits than women. The biggest disparities are found in Spain, where female pensioners have about 30 per cent lower. In Cyprus, the difference is 27 per cent and in Italy it is 18 per cent. Interestingly, in the Netherlands women have pensions that are up to 20 per cent lower, which is most likely the consequence of part-time work.

In some countries, women even have a higher replacement rate than men and earn better than when they were working at around fifty years of age – that is the case in Estonia, Slovakia and Latvia.

(Infographic Bogusław Rzepczak)

The introduction of an almost universal child-care benefit amounting to PLN500, combined with family policy instruments virtually eliminates poverty in multi-child families. The problem, however, is that it will probably cause a further deactivation of women in the labor market. As a result of the reforms, in the next several years more than 200,000 women will likely leave the labor market, although 278,000 additional Poles will be born.

(Infographic Bogusław Rzepczak)

It is estimated that the 500+ program will discourage women with low skills and earning less than their partners from working. Especially those who work on a part-time basis will quit their jobs. In Poland, 8.8 per cent of women aged 25-54 are employed in this way. The 500+ program will increase their income to such an extent that up to 40 per cent of them may give up work or move into the black economy in order to be eligible for benefits for the first child.

As a result, the number of people on the labor market will fall by about 200,000 and the professional activity rate of women will decrease by about 3 percentage points. For example, in Russia after the introduction of a family benefit amounting to USD11,000 per year, the professional activity rate for women working part-time fell by 1.1 percentage points. It can be assumed that the effects will be similar in Poland, especially considering that Polish society has a similar attitude to the professional activity of women and men.

The second big planned change is either lowering the retirement age or maintaining it at the current level. The latter would mean that in the coming years women could retire at the age of 61 and men at the age of 66. The raising and equalization of the retirement age of both sexes would be stopped at the level of 2016.

For a few years this change would be budget-neutral, because thanks to the so-called zipper mechanism (that is the fact that for 10 years prior to retirement the funds from Open Pension Funds are gradually transferred to the Social Insurance Institution), the budget would have to pay less to subsidize paid-out benefits. Their amount, however, is a separate issue. Women simply lose due to their shorter working. Ninety per cent of Poles retire within a month of obtaining the right to pension benefits. Few will work longer without the hope of receiving higher benefits. Without the incentive in the form of the retirement age, it will be difficult to extend the professional activity of women.

It could be argued that because women have been occupied with housework instead of pursuing a career, women should retain preferential retirement terms, but why has the legislature never suggested a way of converting the unpaid family work into retirement benefits? Such a solution would at least be fair and, above all, it would increase the amount of the benefits that women receive. Today, because women work less and earn less, in the autumn of their lives they simply receive less money.

This is a major problem for Poland. Social attitudes shape economic relations, and because of these women in our country are less economically active. As a result they become one of the basic reserves in our labor market, because by encouraging them to greater activity, we are able to increase our potential economic growth.

In addition, each new generation of women is better educated than men – they outdo them at school and in the OECD PISA survey, more frequently pass high school leaving exams, and do so with higher scores. This potential should not be wasted by shaping state-level instruments in such a way that women choose to work less and instead devote themselves to housework.

The author is an analyst at the Polityka Insight think-tank.