(Chris Potter, CC BY 2.0)

In June 2020, the European Commission released its survey “Special Eurobarometer 502” on perception of corruption across the European Union member states. The research was conducted in December 2019, based on 27,498 in-depth interviews with respondents from different social and demographic groups.

The survey is an attempt on part of the European Commission to measure efforts in the fight against corruption in EU member states. To be able to measure the phenomenon of corruption over time, the Commission uses opinion surveys of perception of corruption by businesses and general public. So far, these surveys have been conducted in 2005, and repeated in 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2017.

In the latest survey, 69 per cent of all respondents said that they consider all forms of corruption unacceptable. “In detail, less than a quarter think it is acceptable to do a favor or give a gift (both 23 per cent) to get something from a public administration or a public service. Less than a fifth (16 per cent) share that view about giving money,” the report says. On the other hand, 71 per cent of interviewed Europeans think that corruption is widespread in their country. “Around half consider corruption to be widespread among political parties (53 per cent) and politicians at national, regional or local level (49 per cent),” the report says.

However, most people say that they have not experienced corruption on a personal level. “Just over a quarter of respondents say that they are personally affected by corruption in their daily life. Over one in ten Europeans personally knows someone who takes or has taken bribes, with proportions varying from 28 per cent in Lithuania to 5 per cent in the United Kingdom,” the report reads.

Regional differences

European averages are one thing, but it is important to keep in mind that there are rather significant differences in the way people perceive corruption in the 28 EU member states (United Kingdom was included in the survey).

Moreover, people also tend to have different attitudes towards different forms of corruption. For example, in certain parts of Europe, people seem to be somehow lenient towards giving gifts or doing favors in exchange for services from public officials. However, in the same countries, most people consider unacceptable to give money to achieve the same goal.

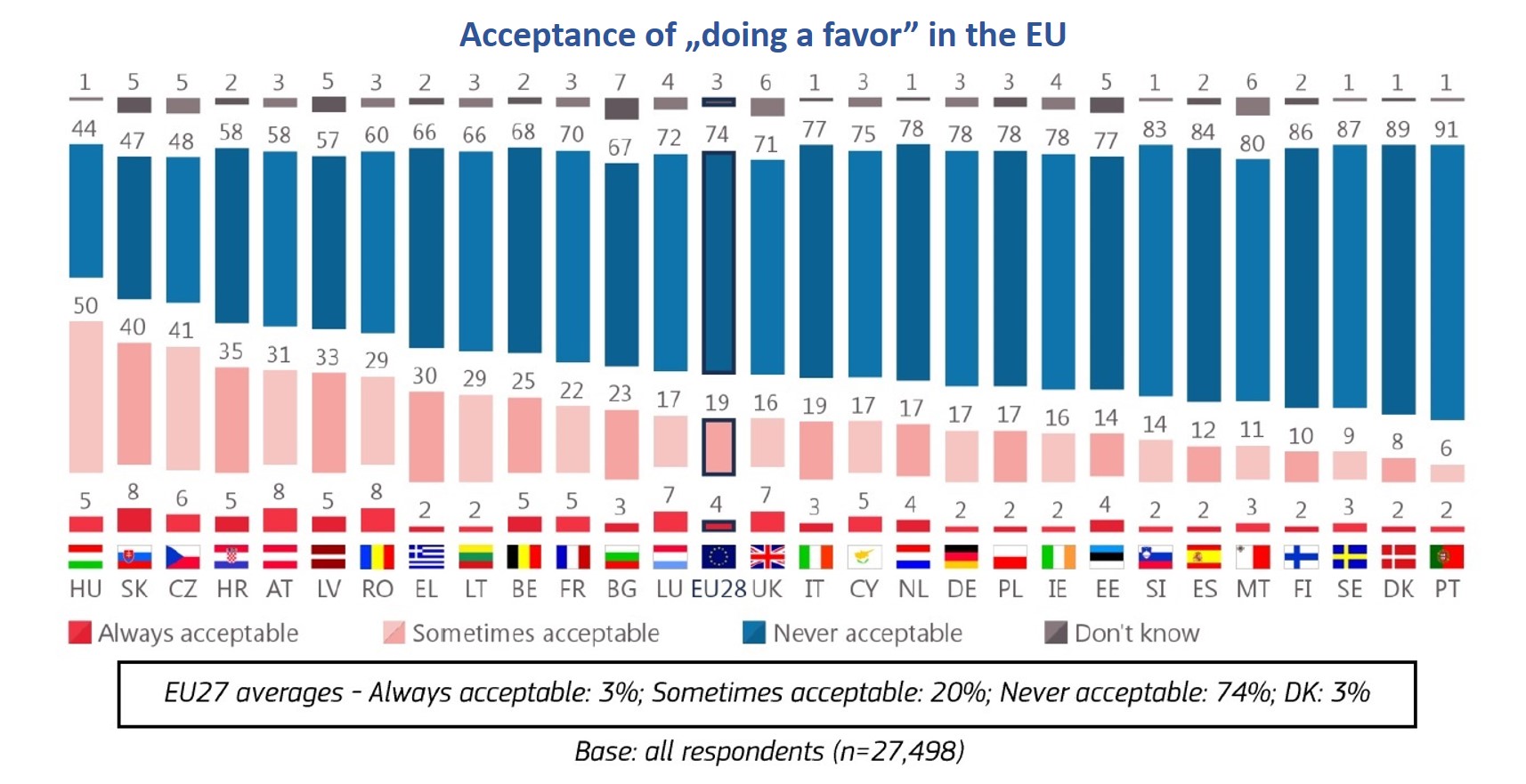

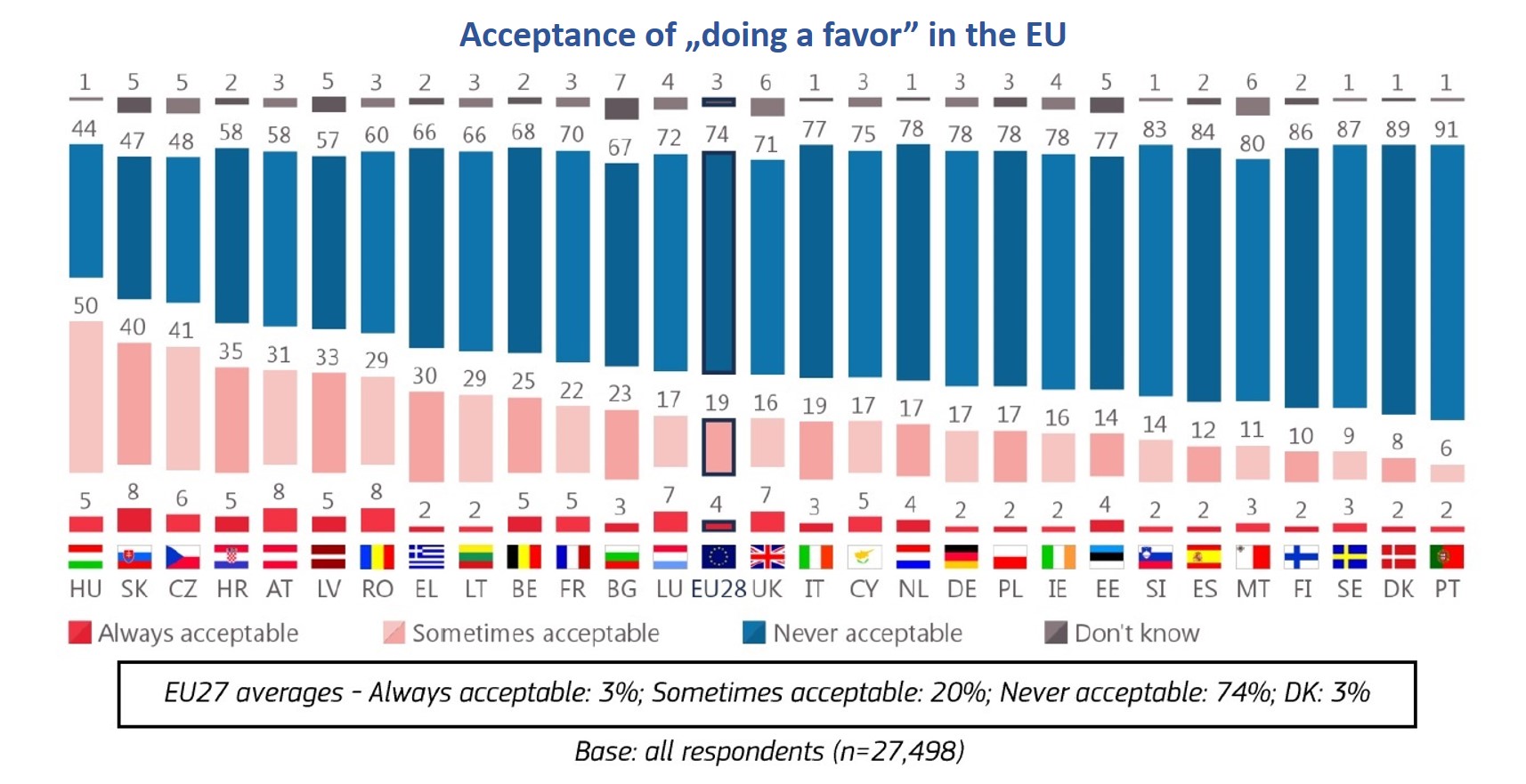

“Doing a favor” to get something of value from a public administration or a public service is an acceptable form of behavior only to a minority of respondents. However, there is a clear divide across the EU on this issue. The top ten countries (highest tolerance) are the following: Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Croatia, Austria, Latvia, Romania, Greece, Lithuania and Belgium. Most of them are the postcommunist countries of CSE.

The list of top ten countries with the lowest tolerance for “doing favors” clearly shows the regional divide. The least tolerant countries are the following: Portugal, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Malta, Spain, Slovenia, Estonia, Ireland and Poland.

The same divide is shown when looking at the perception of “giving a gift” in order to get something from a public administration. The most tolerant countries towards this form of bribe are the following: Latvia (57 per cent), Hungary (56 per cent), Czech Republic (50 per cent), Croatia (49 per cent), Romania (45 per cent), Austria (44 per cent), Greece (42 per cent), Slovakia (39 per cent), Lithuania (37 per cent) and Bulgaria (33 per cent). The top least tolerant countries are: Denmark, Portugal, Finland, Sweden, Spain, Netherlands, France, Luxemburg, Germany and Malta.

We can see a clear pattern here. Generally speaking, giving a gift or doing a favor to a public official in exchange for service is seen as less of a problem in postcommunist countries of the CSE. This presumably comes from old habits of people used to operate in the communist regime when such behavior was oftentimes the only way to receive any public service. On the other hand, particularly for respondents in northwestern Europe, such behavior is seen by the vast majority as completely unacceptable.

Interestingly enough, the lenience of Central Europeans towards some forms of corruption practices does not automatically mean the acceptance of all forms. This is clearly seen in the case of “giving money” to public officials in exchange for favors. The vast majority of Europeans, including those living in the postcommunist countries, consider this form of bribe as unacceptable, with the highest level of tolerance being recorder in Hungary (43 per cent), Romania (37 per cent) and Austria (28 per cent).

Shifting attitudes

Based on all of the above mentioned categories, the authors of the report created a “Tolerance to corruption Index”. It shows prevalent attitudes to all forms of corruption in all 28 EU member states. The lowest tolerance to corruption was recorded in Portugal, Finland and Spain, where more than 80 per cent of respondents said that they consider corruption unacceptable. On the other end of the spectrum were Romania, Slovakia, Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Latvia and Hungary. In all those countries, more than 50 per cent of respondents said that they consider corruption acceptable in certain situations.

The statistics also show that the perception of corruption is changing over time all across Europe. However, the biggest changes are seen, again, in CSE. For example, “the proportion of respondents who believe it is never acceptable to give a gift in exchange for something from a public administration or a public service has increased since 2017 in 11 EU Member States, mostly in Poland (72 per cent), Slovakia (58 per cent) and Latvia (42 per cent),” the report says.

Similarly, since October 2017, the “proportion of respondents who believe it is never acceptable to do a favor in exchange for something from a public administration or a public service has increased in 11 EU Member States, most notably in Latvia (57 per cent), Slovakia (47 per cent) as well as in Portugal (91 per cent) and Hungary (44 per cent).”

So, even though perception of corruption is not the same as the actual prevalence of corruption in any given country, the report shows at least two interesting things. One is the fact that even though people in postcommunist countries of CSE are more tolerant towards giving gifts and doing favors to public officials in exchange for something they want, this tolerance doesn’t extend to giving money, a practice seen as unacceptable as in most countries in Europe.

Another important finding is that the perception of corruption is changing in the region, with less people considering all above mentioned forms of corruption as socially acceptable behavior.

Filip Brokeš is an analyst and a journalist specializing in international relations.