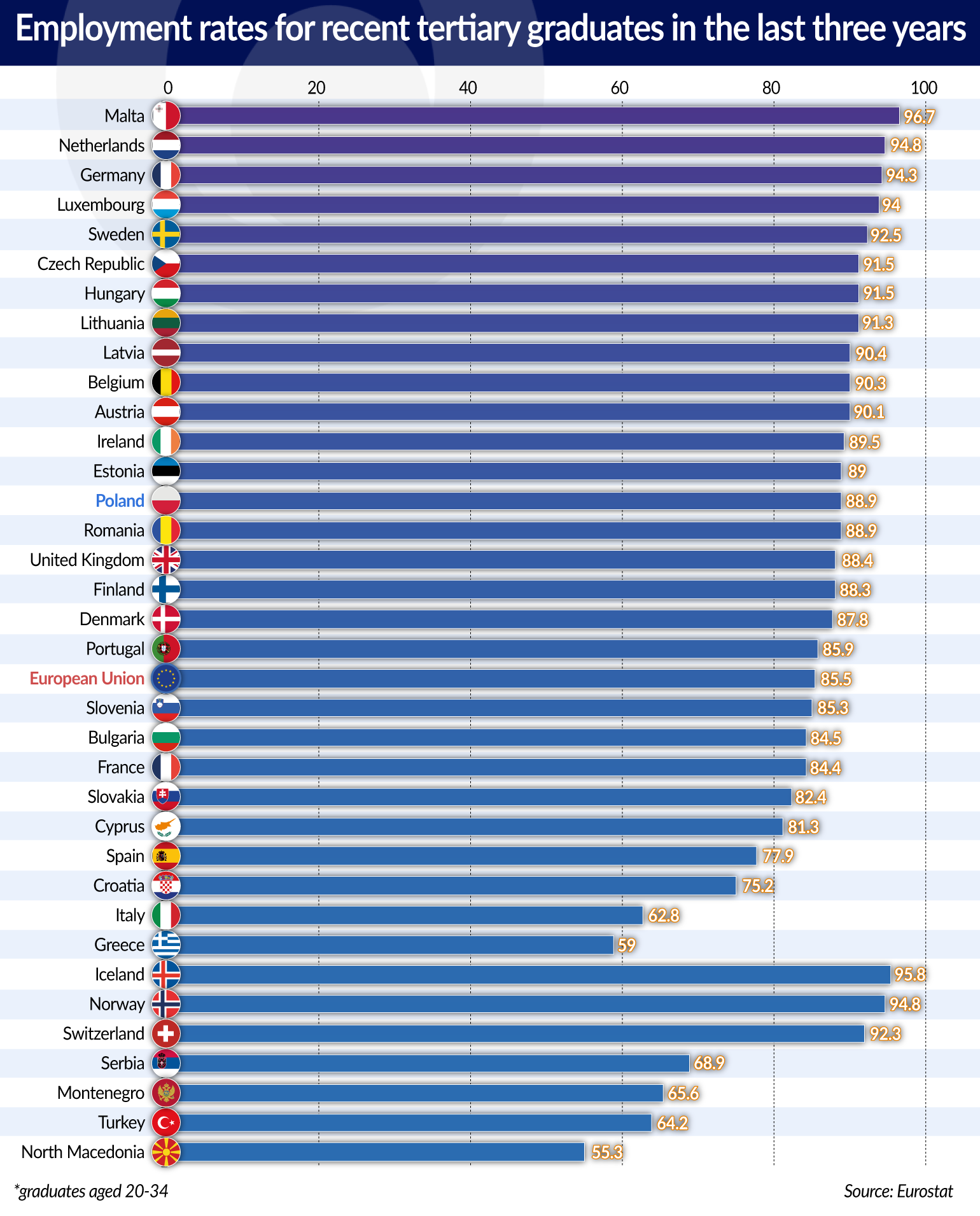

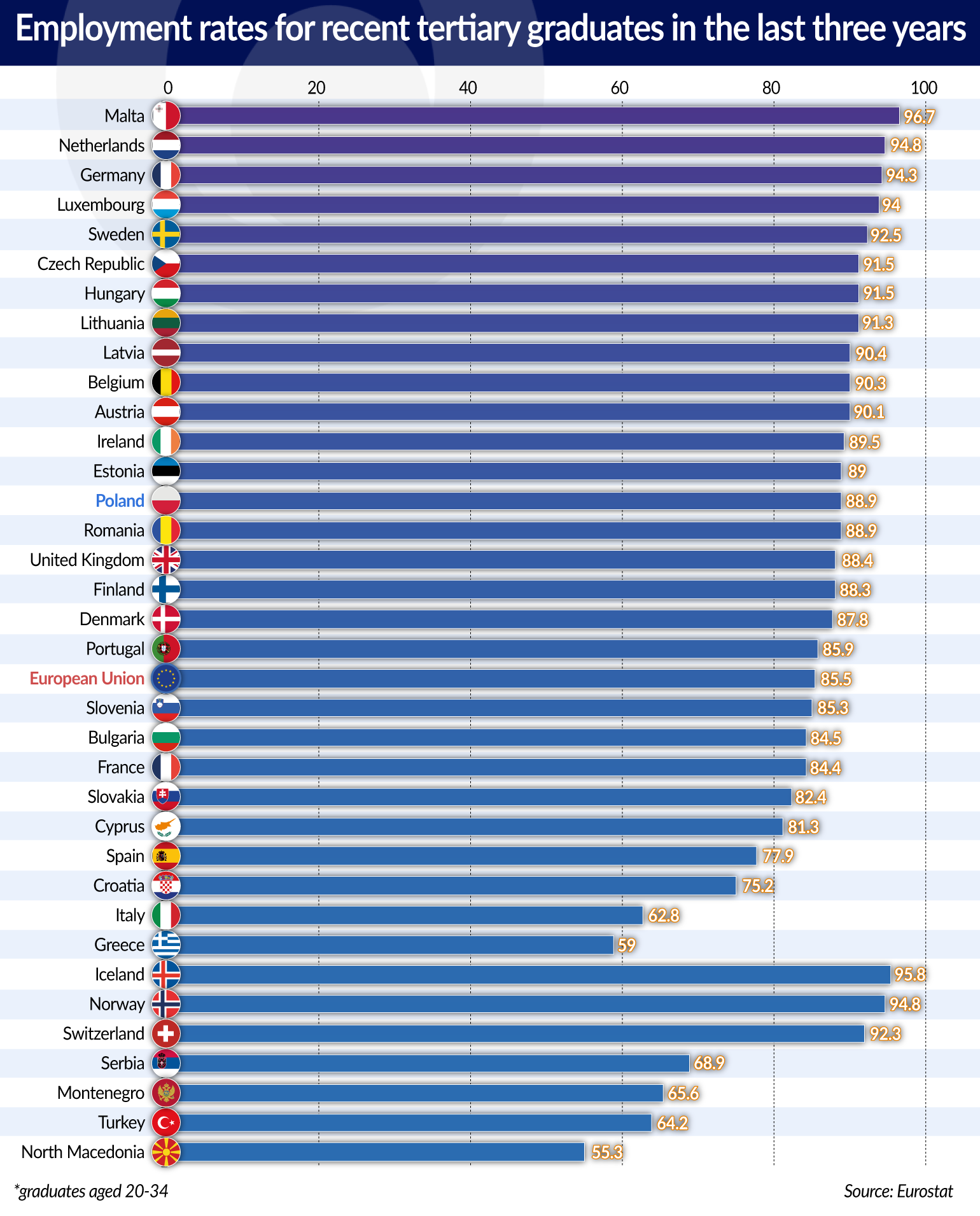

Europe is currently experiencing a period of the lowest unemployment rate on record. This has a positive effect on the section of the labor market which had been the most acutely affected by the shortage of job offers over the last decade, i.e. the new entrants on the labor market or people in the initial phases of their professional career. According to the calculations of Eurostat, for graduates aged 20-34 in the European Union, who had attained a tertiary-level education within the last three years, the employment rate was 85.5 per cent. This rate is higher than the year before, but is still worse than in 2008 when it reached 86.9 per cent.

Poland fared pretty well compared to the EU average, with a graduate employment rate of 88.9 per cent — the same as Romania. However, a total of 13 countries achieved a better result, including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

The best result in terms of the employment rate among recent graduates recorded in Malta shouldn’t be surprising, because Malta, which has a population of less than half a million people, is well-known in Europe and the world not only for its tourism, but also the financial and IT services, thriving ports and a robust fishing industry controlled by family-owned businesses. The employment rate among recent graduates on the island reached 96.7 per cent, while the overall unemployment rate was 3.5 per cent (May 2019).

The other end of the scale, the peripheries of Europe

Significantly worse results can be seen on the other end of the scale — the EU average was brought down by two countries from the group of the so-called old EU member states: Italy and Greece. These countries have recorded the worst results in the entire EU. Their rates of employment among recent graduates are even lower than those in Serbia, Turkey and Montenegro, which are also included in Eurostat’s figures. In Greece, Italy and Spain, the total unemployment rate is still higher than before the crisis of 2008-2009.

From the perspective of mid-2019, the overall employment targets set for Greece for 2020 seem to be unattainable. At the end of 2018, the employment rate in Greece reached 59.5 per cent, and the target for 2020 is 70 per cent. The structure of the Greek economy is not particularly helpful — about 80 per cent of GDP is generated by services, mostly the tourist sector and maritime transport. Industry only accounts for approximately 15 per cent of the country’s GDP.

Growing importance of university graduates

Eurostat has also noted that young people with higher levels of education have the highest employment rates and are generally better protected against the risk of unemployment than their peers who entered the labor market with lower levels of education.

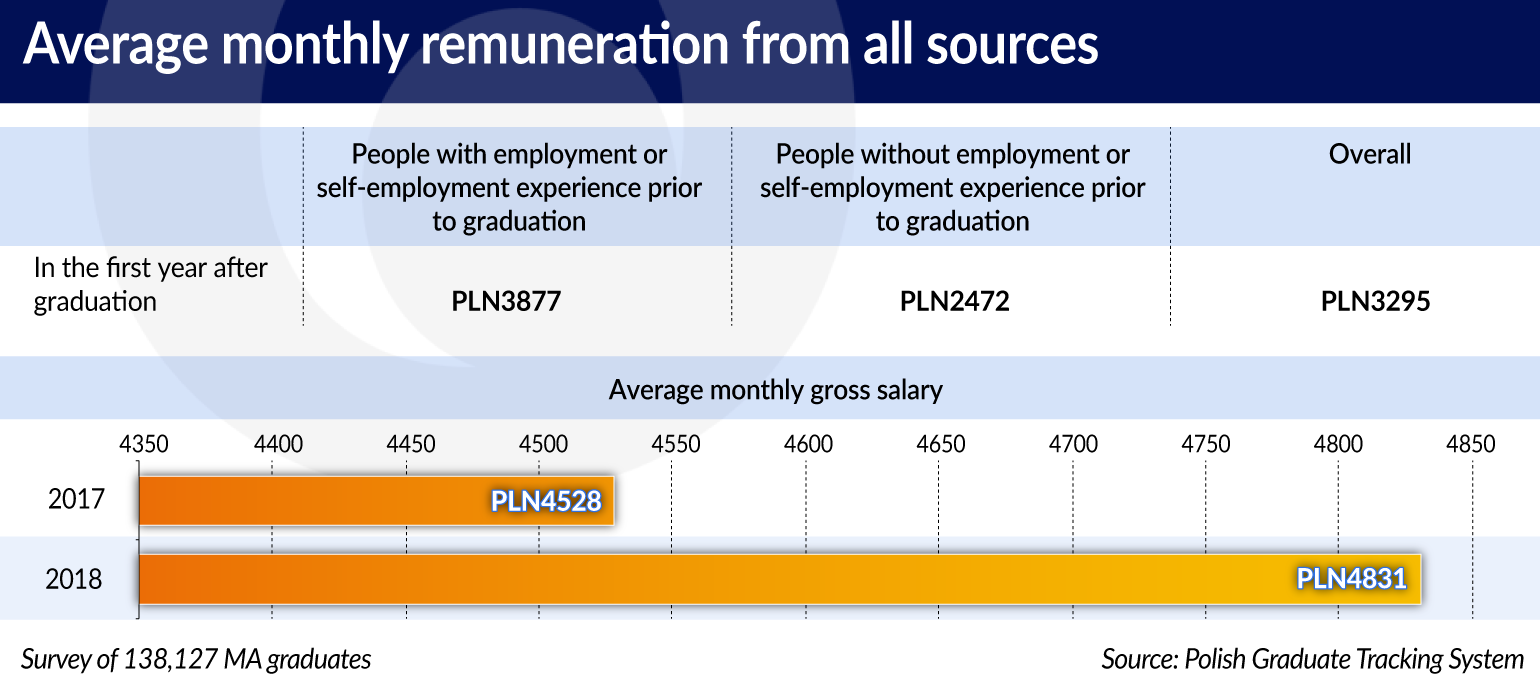

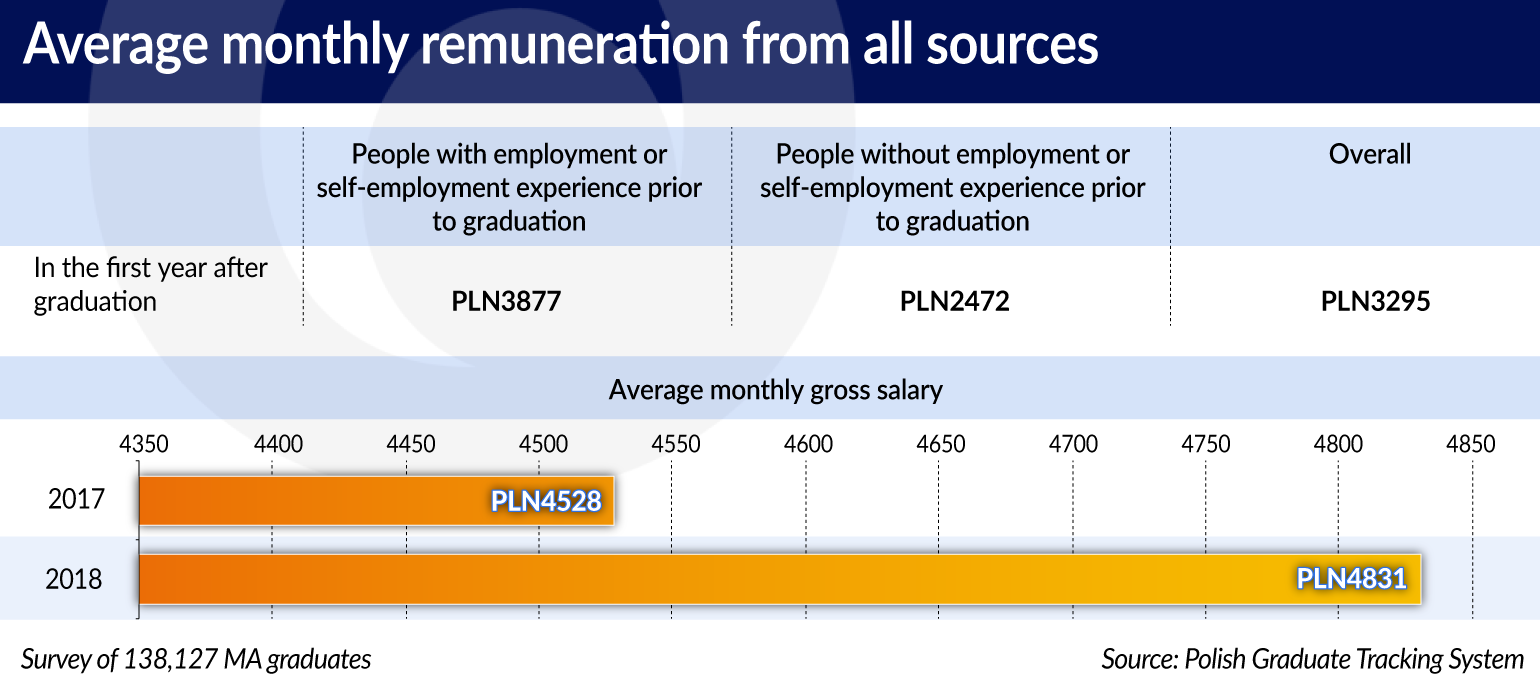

Research that has been carried out since 2014, within the framework of the Polish Graduate Tracking System (ELA) sheds some light on the initial experiences of students entering the labor market in Poland. In the study of 138,127 students who graduated in 2017 (more recent data are not available yet), two main trends stand out. Firstly, a growing percentage of students are working during their studies. As many as 53.8 per cent of those who finished their studies in 2017 had already acquired some professional experience prior to graduation (regular employment, self-employment). Secondly, this experience matters to the employers — graduates with some work experience find jobs easier and are generally better paid in their first year of work compared with their colleagues without any experience.

Employment of any sort in the first year after graduation was declared by a total of 88 per cent of graduates. However, this rate reached over 96 per cent in the group of students who had already been working during their studies and amounted to 78.2 per cent among those who had no such experience. A total of 77.1 per cent of the overall population of surveyed graduates worked pursuant to an employment contract at that time. Meanwhile, such employment was declared by almost 90 per cent of those with prior experience and by 62.2 per cent of those with no previous workplace experience. Unemployment in the first year after graduation was also much more common among those who hadn’t been working during their studies (28.4 per cent) compared to those who had been professionally active in some way during their studies (10 per cent).

A comparison of the average salary of university graduates in the first year of employment in 2017 and the salaries of graduates in 2014 shows that the value of graduates in the eyes of Polish employers is growing. In 2014, the average remuneration — taking into account all sources — of a graduate with a master’s degree was PLN2606 (EUR606). Meanwhile, in 2017 graduates were already earning slightly more in the first year of employment, with an average remuneration of PLN3295 (EUR767).

Unfortunately, the ELA study did not include the self-employed in the summary of earnings (even though they accounted for 7 per cent of all the respondents).

The increase of female scientists

The Polish higher education system can certainly boast about its share of female scientists. According to the latest edition of the ranking prepared by the Centre for Science and Technology Studies at Leiden University, Poland is a shining example of a country where women excel in science. The Medical University of Lublin ranked first and a total of seven Polish universities were included in the top ten in the gender equality ranking.