Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

Coal-fired power plant, Warsaw, Poland (PanSG, CC BY-SA)

The prices of electricity in Poland have been rising rapidly for quite some time. The rising costs of electricity are mainly the result of a dramatic increase in the prices of carbon dioxide emission allowances. The European Commission has been pushing for that increase for several years and has finally succeeded.

There are several reasons for rising electricity prices. Firstly, electricity producers in Poland are in the process of heavy investment (including the construction of new power units), which is strongly reflected in their costs and, consequently, in their prices. These investments primarily result from the need to comply with the requirements of the European Union’s climate policy, which forces the industry to invest enormous amounts of money in technologies that reduce CO2 emissions. Secondly, the prices of coal have increased significantly in recent months (by 20 per cent in 2017), and it is the main fuel used for the production of electricity in Poland.

Thirdly, wholesale prices of natural gas, which is increasingly used in the production of electricity in Poland, have also grown. The prices of the so-called green certificates, received by companies generating electricity from renewable sources, have increased even more (the costs of these certificates are included in the prices of electricity).

However, the factor that has contributed the most to the increase in electricity prices was the dramatic several-fold increase in the prices of CO2 emission allowances. All coal- and gas-fired power plants in Poland must purchase them, as their electricity production is accompanied by high CO2 emissions. In mid-2017 the price of these allowances was EUR4 per ton. Then it had embarked on an upward trend, but had not exceeded EUR7.5 by the end of 2017. A sharp hike occurred in August and September of 2018, when the price of emission allowances broke the threshold of EUR20 per ton.

At that price level, there is no other factor — apart from the prices of the raw material itself — that has an equally strong impact on the costs of electricity generation in Poland. In Polish power plants and combined heat and power plants, the production of 1 megawatt hour (MWh) of electricity is accompanied by emission of 0.8 tons of carbon dioxide on average. The price of CO2 emission allowances is currently EUR19 per ton, and over the course of 2017 the average wholesale prices of electricity on the TGE Polish Power Exchange increased from the EUR39.2 to EUR62.5-64.8 per 1 MWh. We can therefore conclude, that the dramatic increase in the prices of CO2 emission allowances were the decisive factor in the recent increase in electricity prices.

There is still the question of why the prices of these allowances have increased so much. The Polish Ministry of Energy had argued, that this was due to the „entry into force of the EU MIFID II Directive, which classified the CO2 emission allowances as financial instruments, leading institutions to start trading in these allowances”. For the time being, however, „there is no data on how much such speculation has increased their price”.

It is true that the CO2 emission allowances are perfectly suited for speculative purposes. And there have been some instances in the previous years of their prices growing rapidly and then falling back to the previous level. However, this wasn’t just due to speculation, because these price spikes have been closely linked to the changes in the CO2 emission allowances system announced or introduced by the EC. In fact, that was exactly the objective of these changes: to raise the prices of these securities. Therefore, whenever the EC announced such changes or introduced them, then the demand for the allowances grew, because many people wanted to buy them before they become more expensive. That resulted in a price increase. Perhaps some were buying them only as an „investment”, but others were purchasing the allowances for their own needs. The latter group included companies which are covered by the European Union’s system for the reduction of CO2 emissions, and are therefore forced to purchase the emission allowances. These companies are not limited to power plants and combined heat and power plants, but also include the most carbon-intensive production plants from other industries: refineries, cement plants, metal smelters and glassworks, chemical factories, paper mills, tile and terracotta factories, etc. The dramatic increase in the prices of CO2 emission allowances affects not only the production costs and the prices of electricity, but also the prices of many other goods.

The EC has been doing all that it could for several years, in order for the prices of these allowances to rise to the level we see today: EUR20-30 per ton. The EC did that, because, in its opinion, these prices need to be sufficiently high in order to create an incentive for the EU energy sector and industry to limit their CO2 emissions, which is the necessary condition for the effectiveness of the EU’s climate policy. The carbon dioxide emission allowances system is precisely the core element of that policy.

This system, known in short as the EU ETS (Emissions Trading System), was launched in 2005. It covered 12,000 most carbon-intensive (releasing the most CO2 into the atmosphere) production plants in Europe. Before that, EU authorities were considering one other alternative solution as the basic tool of their climate policy: a carbon tax, imposed on all goods whose production or consumption results in carbon dioxide emissions. Such a tax would be added, for example, to the prices of car fuels.

However, Brussels ultimately opted for the EU ETS, after determining, that this system would be more effective, because it would be based on a quasi-market mechanism. Among other things, it was assumed, that the companies covered by this system would receive some of the CO2 emission allowances for free. Over time, the free pool was supposed to shrink, and eventually disappear — so that companies would have to pay for every ton of CO2 released into the atmosphere.

For the time being, the plants „incorporated” into the EU ETS system are still getting some emission allowances for free. The embedded market mechanism is based on the idea that a company which limits its emission will either be able to reduce the number of allowances it has to purchase, or will generate a surplus of such allowances and will be able to sell them. This is why this scheme was officially named the EU Emission Trading System.

The problem, however, was that almost from the very beginning, the price of CO2 emission allowances was lower than the EC had been assuming. It was too low for the companies covered by the EU ETS to provide any incentive in order to substantially reduce their emissions down to the rate expected by Brussels. This is due to the fact that investments leading to reduction of emissions are very costly and only make economic sense if the price of the allowances is sufficiently high.

At some point, the price of CO2 emission allowances even started to rise, but following the crisis in 2008, the price dropped once again to a very low level of EUR5-7 per ton and showed no signs of rising again. That is why the EU authorities decided to cause a several-fold increase in the price using administrative methods, by artificially and authoritatively limiting the pool of available emission allowances.

Brussels decided to use two tools limiting the supply of CO2 emission allowances. First, it applied so-called backloading, where a part of the emission allowance pool is shifted to subsequent years. And now, at the beginning of 2019, the EU launched the so-called Market Stability Reserve (MSR), which functions in a similar way as the intervention purchases of agricultural products. When Brussels determines, that the price of emission allowances is too low, then some of them will be „taken off” the market, and placed in the aforementioned reserve. Meanwhile, when the price is too high, then they will go from the reserve onto the market, increasing the supply and thus reducing the price.

However, MSR has been designed in such a way that it will also include the allowances that have been pushed back for the subsequent years as part of the backloading scheme. The result will be a permanent reduction in the supply of allowances by up to 1/4 from January 2019.

However, such a price is still very high, and is especially affecting the Polish (the production of electricity from coal is accompanied by CO2 emissions two times higher than in the case of gas-fired plants).

The high prices of allowances are much less harmful for many EU member states than to Poland, as its energy sector, based to the greatest extent on coal fired plants, is the most carbon-intensive in the EU. Other EU members have a much larger share of electricity produced from less carbon-intensive gas-fired power plants, from zero-emission renewable energy sources, as well as from nuclear power plants which are considered „climate neutral”. Nuclear power plants release such tiny amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, that they haven’t even been covered by the European Union’s system for emission reduction.

Poland’s problem lies in the fact that it is the only member state of the EU still extracting significant amounts of hard coal. Although brown coal is also extracted in the neighboring Germany and the Czech Republic, both of these countries also have nuclear power plants. Additionally, in Germany the share of zero-emission renewable energy in electricity production is far greater than in Poland. The construction of nuclear power plants and offshore wind farms on the Polish coast of the Baltic Sea, which is planned by the Polish government, will not be enough to solve Poland’s problem. either.

This is due to the fact, that these investments will be very costly (among other things, due to the necessity of building new power lines that will connect these power plants with the national grid), and will also take years to complete. The first nuclear power plant in Poland will be built in 10 years at the very earliest. Almost as much time will be needed in order to prepare and build offshore wind farms and to connect them to the national transmission network. The costs of these investments will have to be included in the price of electricity, which means, that the prices certainly won’t be reduced in the first years of operation of these power plants.

And there is no reason to expect that the EU authorities will respond positively to the appeal of the Polish Ministry of Energy and increase the supply of CO2 emission allowances in order to significantly reduce their prices. Moreover, experts predict that the prices of allowances will rise even higher and will remain at such a high level in the coming years. Such an opinion was presented, among others, by the analysts at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. According to them, the price of emission allowances in the EU will increase from the current level of EUR19 to EUR35 by the end of 2019. The analysts at Carbon Tracker predict that the prices of CO2 emission allowances will continue to grow, reaching the level of EUR35-40 in 2023.

Such increases are supposed to result from the launch of the Market Stability Reserve, but also from the strong increase in gas prices, which leads to an increase in the production of energy from coal and thus raises the demand for carbon dioxide emission allowances.

Poland’s efforts should go in two directions. On the one hand, it has to look for solutions that can be implemented in the shortest possible time. Only a genuine technological breakthrough in the field of renewable energy could allow the renewable energy sources to replace the fossil fuels: coal, gas, uranium and oil. This means that for the time being, we cannot get away from them, and the core of the power production industry still has to be based on conventional energy sources.

Another solution would be to increase Poland’s energy efficiency, which is still 2-3 times lower than in Western Europe. This means that Poles consume 2-3 times more energy to produce the same unit of GDP. There is a huge potential for improvement, because electricity consumption could be at least 30 per cent lower (the cheapest energy is energy we don’t use). There are many methods to achieve this, including the replacement of regular power plants with combined heat and power plants, as they are much more energy-efficient.

It is also worth focusing on distributed energy generation, that is, building as many small, local power plants as possible, as well as developing domestic micro-generation installations. Prosumers are thriving in the West, many owners of single-family houses or companies are installing photovoltaic panels in order to reduce energy costs. However, such an energy transformation has only just begun in Poland and it will take many years before large power plants are replaced by thousands of local micro power plants providing cheaper electricity.

This means that in the short term Poland should primarily lobby for changes in the EU’s climate policy. In its current form it is not only unfair (it affects the poorer CSE countries), but is also ineffective and harmful to the EU industry.

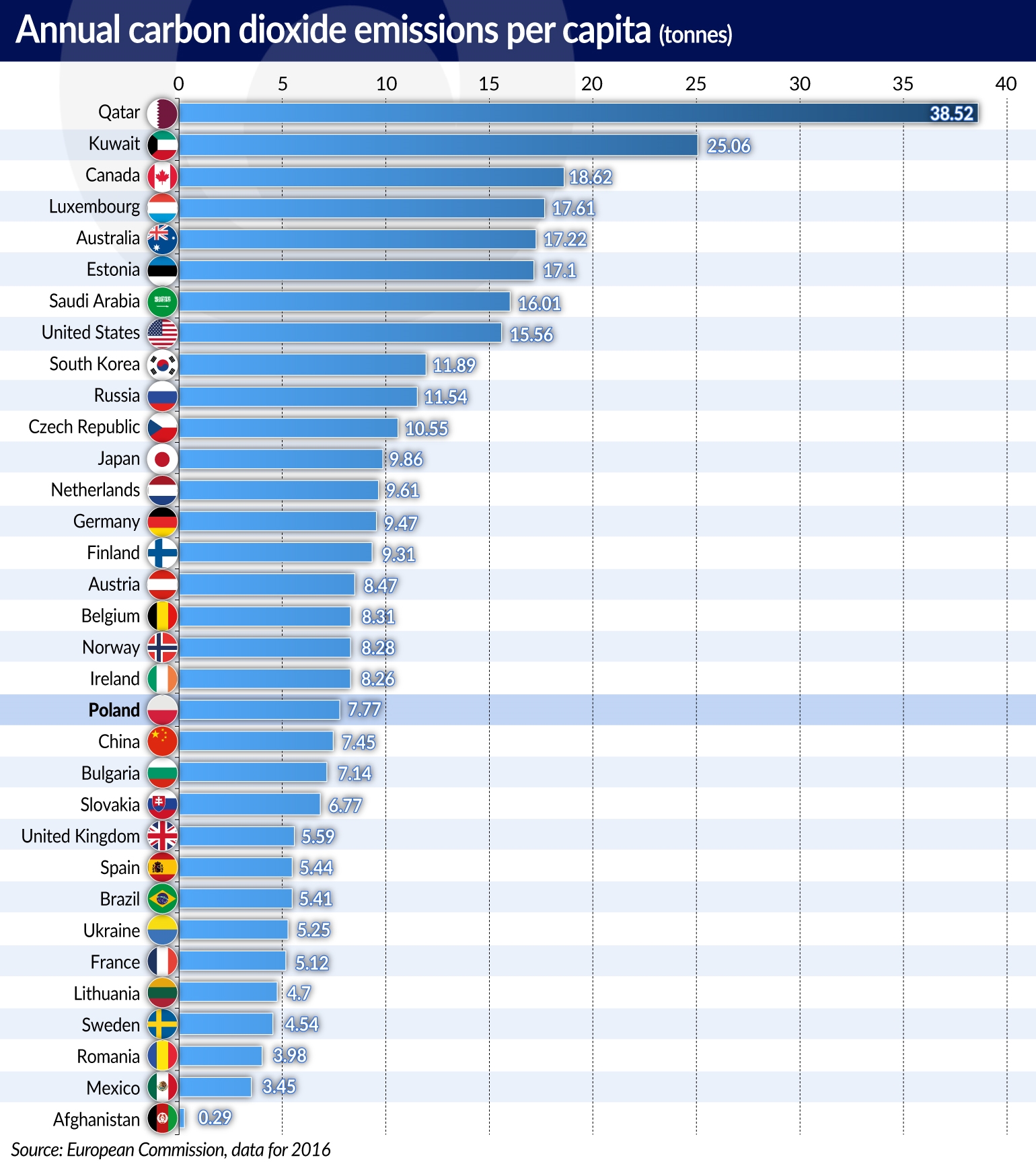

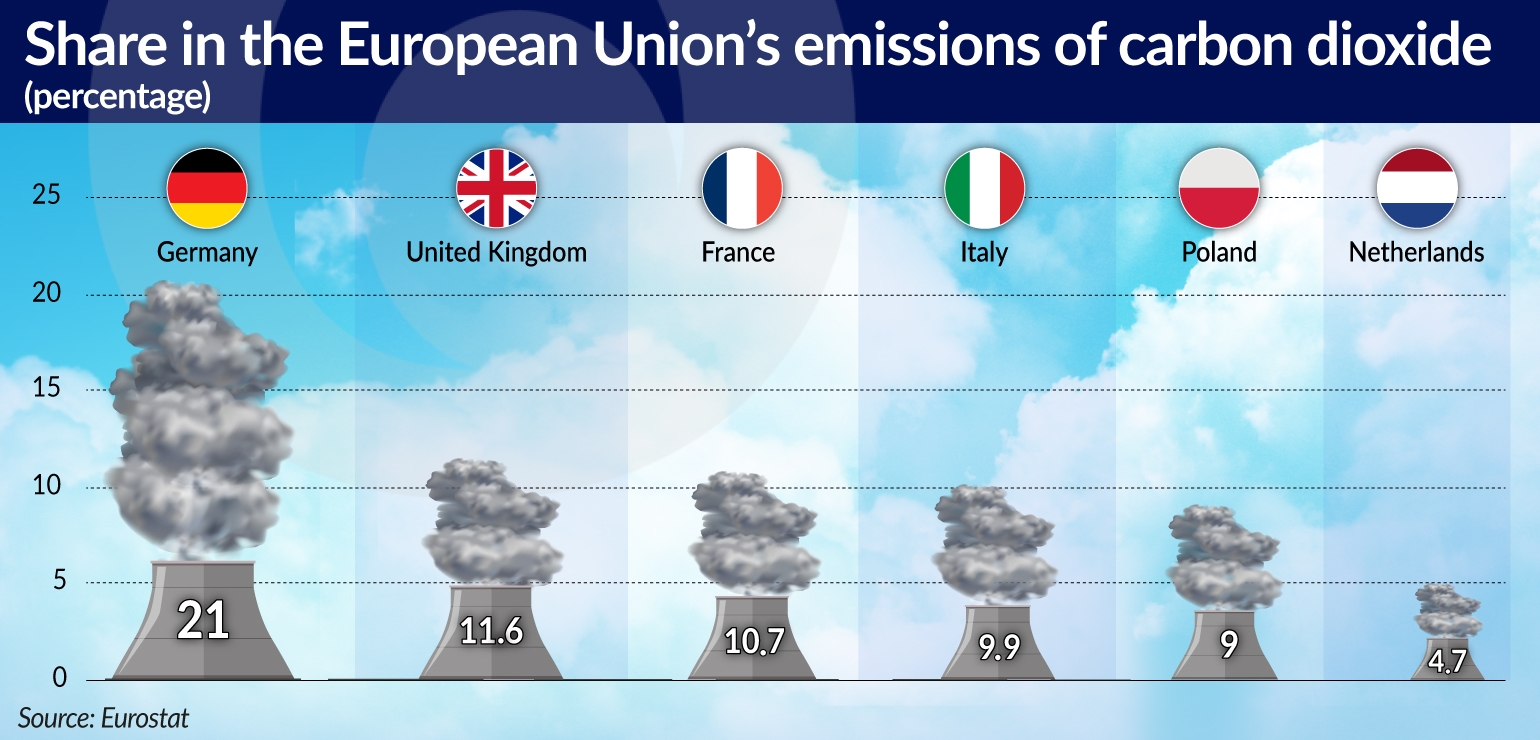

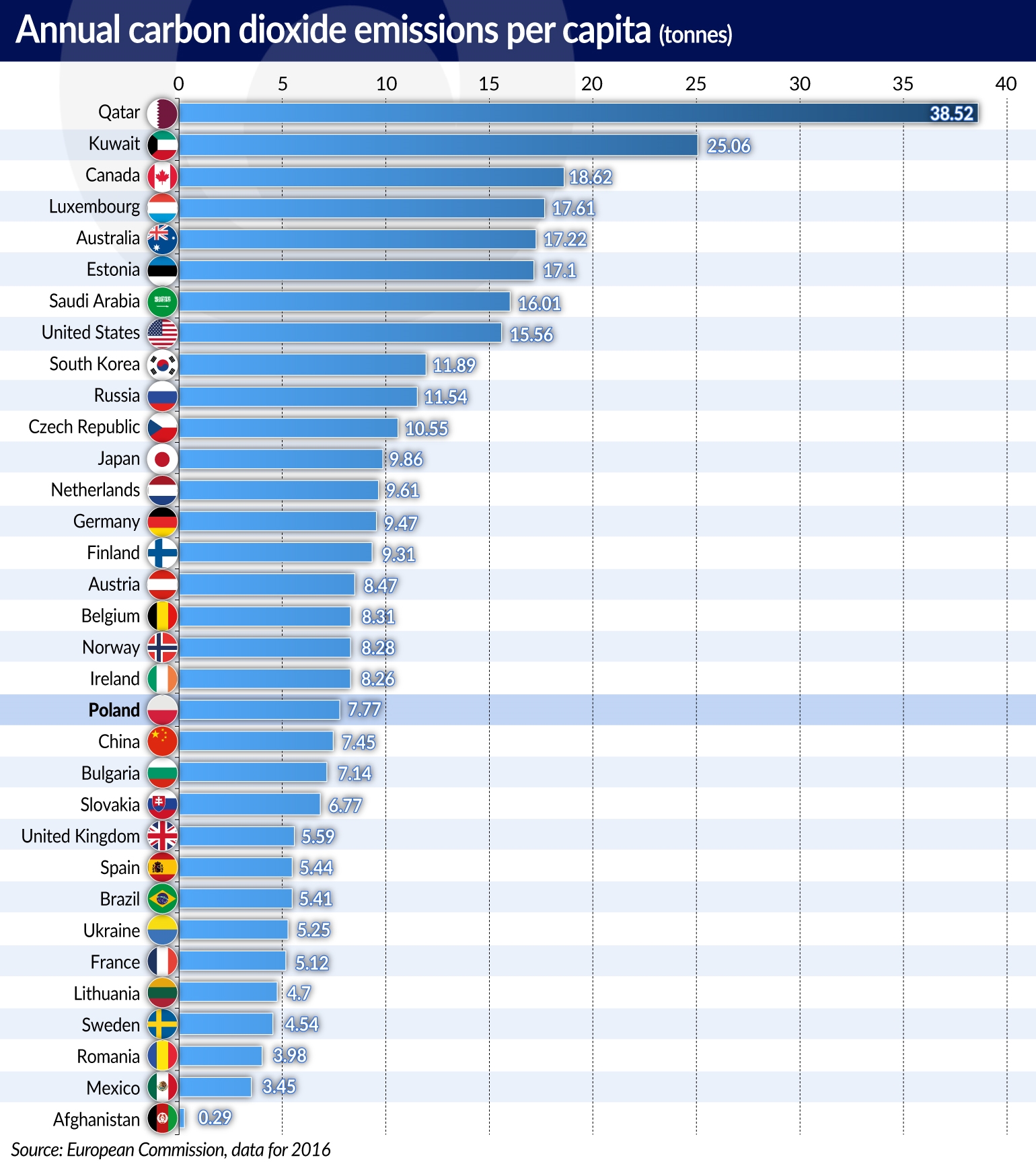

In Brussels, Poland is seen as the EU’s biggest climate culprit, due to high share of coal in its energy sector. But four EU member states have higher CO2 emissions than Poland — Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom, while as many as 9 EU countries have higher carbon dioxide emissions per capita — outside of Germany, this group includes, among others, the Netherlands, Belgium and Ireland.

The EU policy does not produce the desired effects. It isn’t leading to a reduction of CO2 emissions. In the years 2006-2016 the CO2 emissions in the EU only fell by 2 per cent (this is well below the European Union’s previously adopted „reduction” targets), while the emissions in the United States decreased by 1.2 per cent, even though this country doesn’t even have a CO2 emissions reduction system and implements an incomparably cheaper climate policy.

In general, it can be said that when the economic situation in the EU is good and when the natural gas prices are high, then the CO2 emissions increase — because of greater industrial production, higher energy consumption and a higher share of coal in its production. This is true even in countries as committed to the climate policy as Germany.

In per capita terms, CO2 emissions are the lowest in the poor countries (Africa, South America or the poorer part of Asia) and they are the highest in the wealthy countries with a strong industry and in countries which have abundant resources of energy commodities. The highest emission of CO2 per capita in the EU has been recorded in its richest country — Luxembourg — and in the most affluent countries out of the „new EU member states” — the Czech Republic and Estonia.

Nobel Prize winner Romer supports the carbon tax

This means that the main problem, which no one is willing to admit openly, is the excessive and constantly growing consumption, including energy consumption, and not the fact, that we produce it from fossil fuels.

From this point of view, carbon tax seems to be a better and more effective solution. Paul Romer, Nobel Prize winner in 2018, supported this solution, arguing that it would be the best way to reduce CO2 emissions. Carbon tax would be added to the purchase price of all items whose production or use involves CO2 emissions. This means that we wouldn’t all pay equally for the emissions, but each person would pay to the extent to which they contribute to it. This would also help the EU economy, because it would level the playing field for the EU’s industry in its competition with the industries from other continents (especially from Asia) which are not burdened with such high costs of climate policy. This is because the carbon tax would also be imposed on imported goods. This means that instead of decreasing, the emissions are merely „migrating” outside the EU. And that alone is reason enough to change the European Union’s climate policy.