Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

Tver, Russia (Дмитрий Симонов, CC BY)

They are a product of Stalinist industrialization – company towns built around a single plant or factory (sometimes there were more factories, connected to a major one as suppliers). For years mono-towns have been not only the sole employer in the area, but their task was also to provide people with social services and amenities, from health care and schools to electricity and heat.

In Russia there are 319 mono-towns at the moment. Every tenth Russian lives in this sort of community. Taking into consideration the level of their development and living conditions, most of them were frozen in the 1970s or 1980s at best – even though Vladimir Putin’s “modernization program” claimed to “bring industry into the twenty-first century” by making it “science – and innovation-based.”

Take Pikalovo (200 kilometres east from St. Petersburg) as an example. In 2009 its residents vented their anger over job losses and unpaid wages at one of the oligarch’s local factories by blocking a major road and causing a 250-mile traffic jam. Then, at that time Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, arrived to the town to publicly chastise the management for failing to pay workers for the previous three months. Oleg Deripaska, once one of the richest oligarchs, was openly humiliated and hung his head like a schoolboy when Putin, acting like „Sheriff for Cowboy Capitalists” (NY Times comment), was blaming him for mistakes and being greedy and, at the end, ordered him to pay all outstanding wages before the day was out.

Putin was widely praised by Russians for his determination in fighting for their work conditions. Pikalovo residents were lucky. Today it seems that there is not enough power to force mono-towns to operate: a lot of money is necessary to make them going and since Russian economy is going down, nobody even dares to promise financial support.

Wacław Radziwinowicz, correspondent in Moscow of Gazeta Wyborcza (Polish daily newspaper), explains that today every mono-town can expect no more than RUB4,5bn (around EUR230,000) in the public aid programs. This is to help establishing business incubators which could attract investors. But this is not enough – investors will not go to faraway places with old fashioned technology and not sufficient road infrastructure. Most mono-towns are located far from big cities, employees have been working in „their” plants for all their lives and are not familiar with different work standards, not to mention modern technology. This all is a real challenge to the government, which somehow needs to keep mono-towns going to avoid social discontent. But by the end of the day these are mono-towns residents who are going to suffer most, because they have no alternative to their present life.

„Mono-towns will fall into apathy. Active people will leave, others will try to adapt to the harsh living conditions. Authorities will continue to do what they can to prevent the explosion of a formal unemployment. Governors won’t let factory managers dismiss workers and will transfer small amounts of money so that monthly payments can be made. Workers are coming to factories two or three times a week. They clean, paint, do some sort of unnecessary work, but formally they work and earn stable money. But hopelessness and poverty make them drink more and more. Mono-towns will fall into decay. Russia will transform itself into an archipelago of large cities, hundreds of kilometers far from each other” – forecasts Yevgeniy Gontmacher, expert interviewed by Radziwinowicz.

Mono-towns are doing worse each year – and so is the whole Russian economy. Because of the Western sanctions and dropping oil prices, poverty in Russia has reached a „critical level” and even officials, leaving behind Kremlin propaganda, claim the situation is getting out of control. “Unfortunately, predictions are coming true: according to the official statistics, number of poor people has reached 22 million. This is critical” said Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodets in an interview for Russian TV. According to Rosstat’s data the number of people living below the poverty line rose from 19.8 million in the first quarter of 2014 to 22.9 million in the same period 2015. The percentage of Russians living below the poverty line thereby rose to 15.9 percent of the total population in the first quarter. The cost of living in Russia has gone up this year due to an inflation (in the first quarter it was16.2 per cent, while incomes increased by only 11 per cent).

The price increases were a result of Western sanctions on food import from the West along with the collapse in the value of the ruble. Since Russia’s economy is heavily dependent on exporting oil, situation won’t go better as long as oil prices don’t increase which is not very likely in the near future (especially if Iran joins the group of oil exporters as claimed). That all means Russians really need to learn to live on a tight budget.

Russia from times before Putin came to power in 2000 and today – these are two different states if we take into account the conditions of life. In 15 years poverty level fell from 30 to 10 per cent (now soaring but for a number of years it was stable), access to medical services was improved and Russia was, to some extent, striving to become a welfare state. An example of this approach is Russian pension system, which provides several privileges and different retirement age for men and women. On the other hand, pensions are very low and usually don’t secure decent life – but nevertheless the principles itself refers to the ones adopted in welfare states like Scandinavian ones.

A popular belief says Putin bought social contentment by raising living standards and allowing people to make money and spend it the way they want – buy goods, go abroad, invest. After years of misery and watching “wealthy life” only on TV people enthusiastically agreed – even though a part of agreement is they will refrain from interfering in the politics.

The World Bank estimates that up to 2010 Russian middle class controlled 74 percent of the total households income and 86 percent of total household consumption. In the period of 2000-2013 the share of the middle class in the total population increased twice – up to 60 percent of all residents. At the same time, however, the middle class began to delaminate and differences between people representing different professions started to deepen. Social stratification, measured by Gini index is much higher than in Europe, though not the highest in the world.

In December last year one of the centers for public opinion asked Russians what they save money for or would save if they could. 33 percent said purchasing the property is a top priority – in relation to polls carried out in the past, the number of people who declared this increased by 8 percentage points. This proves that Russians want to spend money on something that will keep its value and can be a security in current market turmoil. 22 percent wants to save money for unexpected expenses, the same number – for a rainy day. These two categories go down to one thing: people want to protect themselves in case of life conditions getting worse.

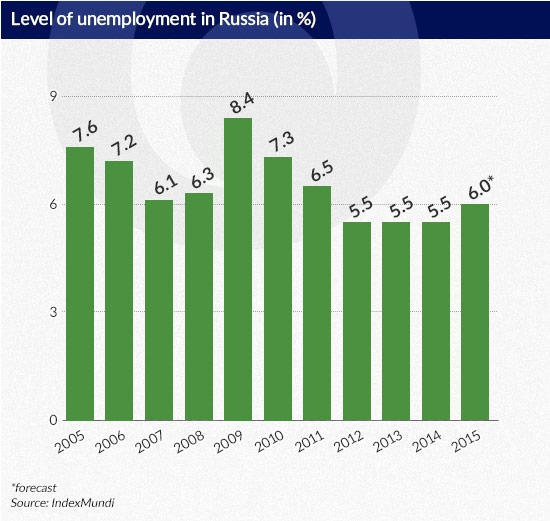

The monthly reports by Rosstat indicate that unemployment is slowly increasing. In January it was 5.5 percent, in February increased by 0.3 percentage points. Out of 144 million Russian residents, only 4.5 million remains jobless.

(Infographics DG)

The above-mentioned figures don’t give a full picture of the situation. The problem of a hidden unemployment is growing in Russia and comes down to what Y. Gontmacher said about mono-towns: “in many companies people don’t have any particular work to do, quite often they don’t even show up in the factory as nobody expects them to do so. In the most extreme situations they don’t get monthly remuneration – but remain formally employed. In reality their situation is not as bad as it may seem because they are still entitled to benefit from different forms of social care like healthcare or free community housing. When the factory (usually the only employer in the area, so people have virtually no choice but to wait for better times) recovers or simply starts to operate again, they will regain the status of a regular employer. When it doesn’t, employees will need to make up for their lives somehow until they retire and can benefit from pension system”.

The World Bank estimates that by 2016 Russian economy will shrink by 4,1 per cent. Unemployment is expected to increase – not only the hidden but also the registered one. Companies that don’t carry on production can’t keep the staff forever and sooner or later will be forced to terminate the contracts. Not only blue-collars are likely to face problems on labor market; sectors related to new technologies are also prone to job cuts. For instance, Ministry of Communications predicts that unemployment in media will soar by 15-20 per cent as a result of loss of revenues from advertising and rising business costs on the other.

One more thing that clearly shows that situation is getting really bad in Russia is steadily declining number of immigrants from post-Soviet republics. This is a surprising phenomenon. The Federal Migration Service reported that in January 2015 the number of migrants has fallen by 70 percent as compared to January 2014. Due to ruble devaluation and general downturn in Russia, the prospects in Federation are dull so they prefer to look for work elsewhere – it can be more profitable and stable when taking into account the majority work illegally in Russia and could not expect to get a fixed contract.