When the first pension systems were being established — in Germany in 1889, in most European countries following the First World War, and in Poland in 1933 — their authors couldn’t have guessed that in less than 100 years demographic trends would make these systems unsustainable.

These early systems were redistributive pay-as-you-go schemes, also known as solidarity-based pension schemes. This means that the benefits received by the elderly are financed with the contributions paid by the younger people who are currently working. Such a system is commonly referred to as the „Bismarckian pension model”, because it was first introduced in Germany, although the vote on that matter actually took place after the „iron chancellor” had stepped down from his office.

Demographic changes are blowing up the pension system

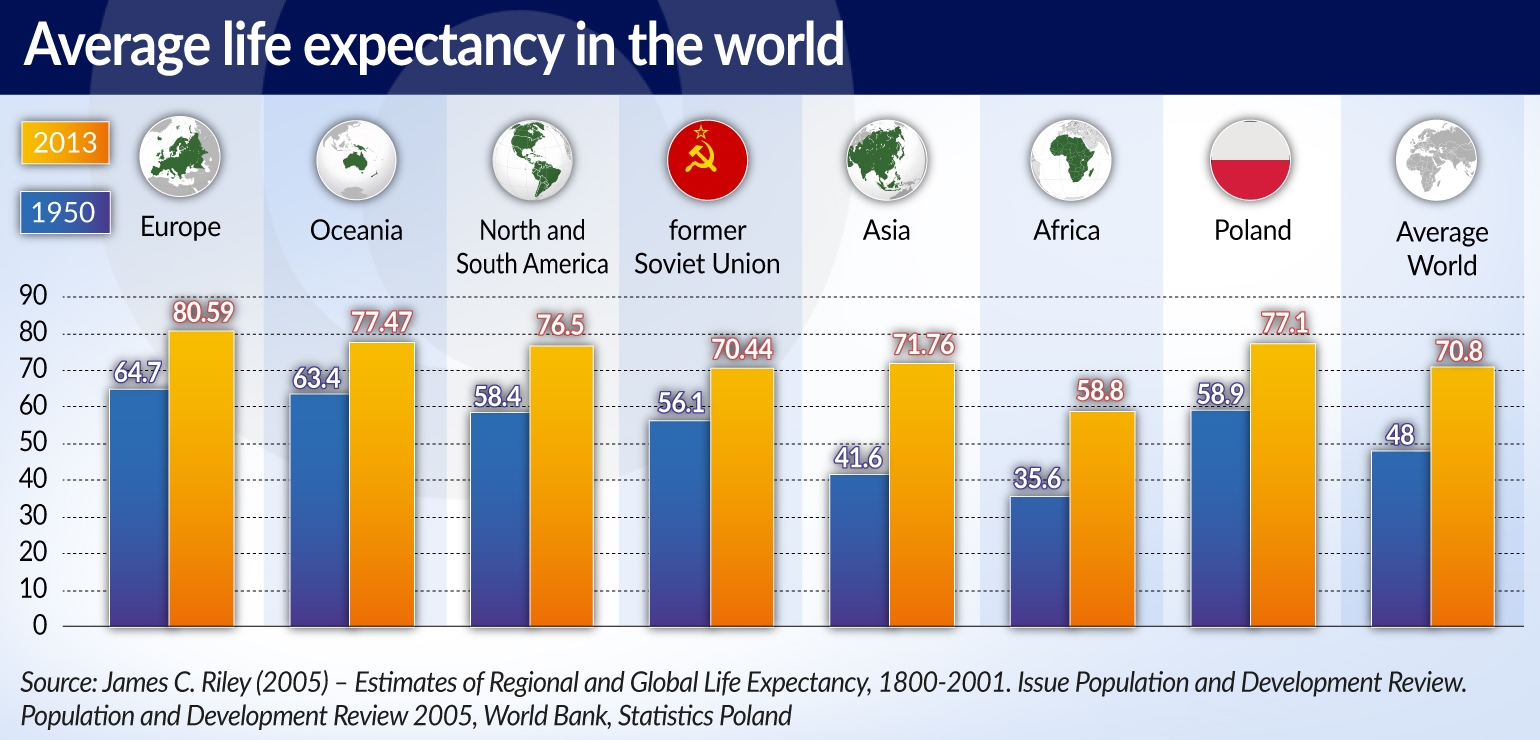

In the late 19th century an average Englishman and a Swede had a life expectancy of 47 years, while a Frenchman was only expected to live 42 years. In 1932, the average life expectancy of a male in Poland was 48 years, and of a Polish women 52 years. At that time a person on retirement faced the prospect of living a few more years, and a large percentage of the workers paying the pension contributions died before reaching the retirement age. This was not a pleasant situation for the payers and the pensioners, but it was healthy for the finances of the pension system. Due to the high annual birth rate, exceeding 10 births per 1,000 people, there were many working people for each pensioner.

It’s also worth noting that pension systems (for example, in the Second Polish Republic) did not cover farmers and self-employed people — shopkeepers, craftsmen, etc. Because of that, in 1935, only 14 per cent of the population aged 14 to 65 years were covered by the Polish Social Insurance Institution. At present, 60 per cent of people from that age group are insured.

A more cautious pension system was adopted in the United Kingdom after the Second World War. In 1942, William Beveridge, a public official from the Ministry of Labor, published a report entitled „Social Insurance and Allied Services”, in which he suggested that all people of the working age should be paying a special tax. In return they could expect state-financed pension benefits which would ensure a minimum standard of living in case of illness, disability or old age. Beveridge’s arguments were accepted both by the Conservatives and by the Labor Party and became the basis of the pension system introduced in the United Kingdom after the Second World War.

Today, the British are paying small contributions which are deducted from their earnings — 12 per cent from a weekly earnings ranging from GBP157-866 and 2 per cent from earnings in excess of GBP866 per week. Contributions are also paid by self-employed persons. The state pension is granted after 35 years’ worth of contributions and after the worker reaches the statutory retirement age (in 2020 the retirement age in the United Kingdom will be 66 years for both men and women). Pension benefits are the same for everyone and amount to GBP164.35 per week. Most British people are also enrolled in other pension systems, including private pension schemes and company pension schemes.

The Beveridge system was a step towards the so-called universal pensions. Such a system is in force in Canada. The Old Age Security (OAS) is a pension for people who are at least 65 years old and who have lived in Canada for at least 40 years. It is financed from taxes, the contributions are not deducted from the earnings, and it is also disbursed to people who do not have a sufficient contribution period. Since 2019, the OAS amounts to CAD601.45. The pension is higher for single people, and lower for married people. It is a benefit that is hardly enough to finance even a very modest life. One advantage of both the Beveridge pension system and the universal pension system is their relatively low sensitivity to unfavorable demographic trends, and thus the low hidden retirement pension debt.

Longer life expectancy, lower pensions

Even 30 years ago, the chart representing the age structure in Poland had the shape of a pyramid, or rather a Christmas tree, with protruding branches depicting the „baby boom” birth cohorts. Today, it has the shape of a barrel: the largest group of people living in Poland — over 650,000 persons — were born in the year 1983.

Meanwhile, approximately 402,000 children were born in 2017, and 388,000 were born in 2018. If this trend continues (and there is nothing to indicate that the situation could change anytime soon), the birth cohorts going into retirement will be far more numerous that the ones that will be entering the labor market. Additionally, due to the extended period of education, young people are now starting work at a later age, which shortens their contribution period.

Almost all countries experienced a significant increase in the life expectancy. This is especially true of developing countries. Across the world, the average life expectancy in the years 1950-2013 increased by 22.8 years, whereby in Europe it increased by 16 years, in Africa 23 years, and in Asia of over 30 years. Poland also experienced a significant increase in life expectancy — of more than 18 years. Today, average life expectancy in most of the European countries, as well as in the United States and Japan, is approximately 80 years. On average, a retiring person in Poland continues to live for about 20 years.

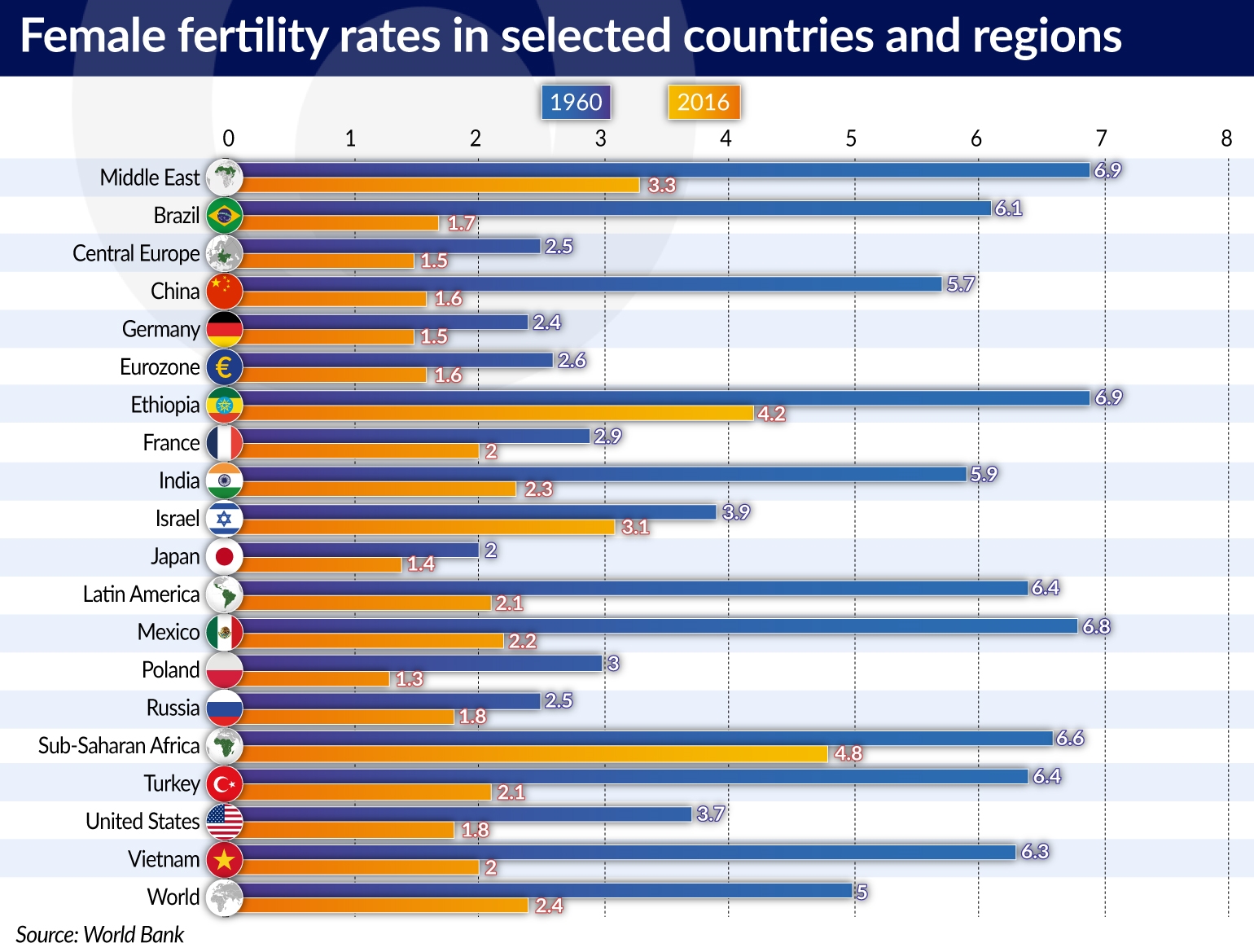

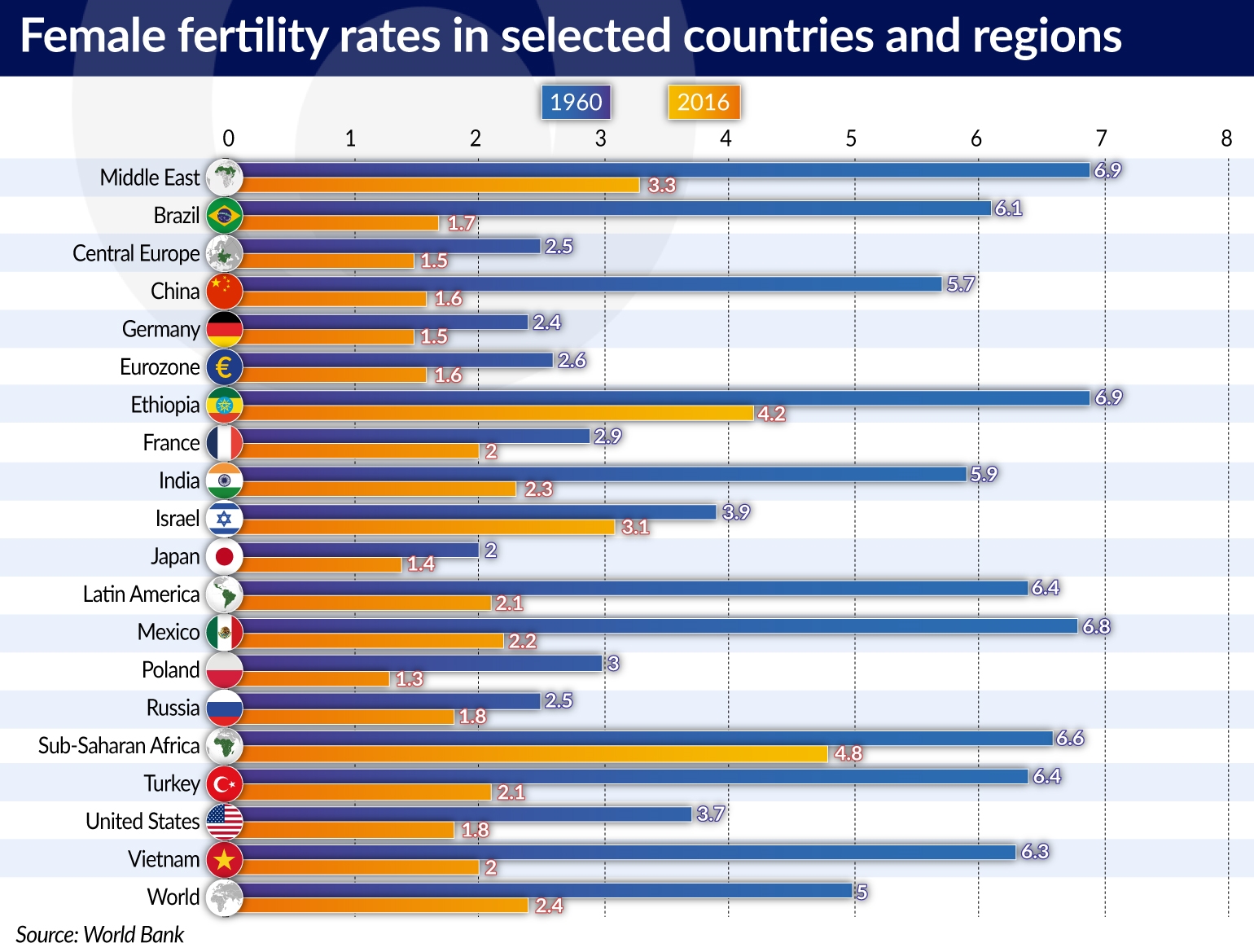

At the same time, there has been a decrease in the female fertility rates (the average number of children born to a woman throughout her period of fertility). This tendency is observed in all countries, regardless of the level of income, the culture and the dominant religion. It’s just that this process is much more advanced in the wealthier countries.

While more children are usually born in the families of immigrants (for example in Arab or Turkish families in Europe), this trend disappears in subsequent generations. The fertility rates in almost all European countries are now lower than 2.1, which is the generational replacement rate. This means that subsequent generations will be less numerous.

Asia is facing particularly serious demographic problems. The demographic changes that took place over 100 years in Europe and North America will occur in Asia over the course of just one generation. In 1960, some 40 per cent of Chinese people were no older than 14 years of age, while today this age group only accounts for 18 per cent of the overall population. During this time, the share of people aged 65 and more in China increased from 4 per cent to 11 per cent. China is still a fairly young society, but it is aging very fast, which will obviously affect the stability of its pension system.

The largest share of population aged 65 and over is currently found in Japan (27 per cent), followed by Italy (23 per cent), Portugal (21.5 per cent), Germany (21.5 per cent), Finland (21.2 per cent) and Bulgaria (20.8 per cent). In Poland people of this age account for 16.8 per cent of the overall population, which puts the country among the relatively young European societies. It’s just that the number of older people, as well as their share in the whole society, are rapidly increasing due to the low fertility rate and the growing life expectancy.

It is very difficult, if not impossible, to stop these demographic trends, let alone to reverse them. Even the extremely pro-natalist policy of the French government has not been able to increase the fertility rate above the 2.0 threshold, while the share of people aged 65 and more in that country increased from 11 per cent in 1960 to 19.7 per cent in 2017.

Multi-tier pension systems are the most beneficial

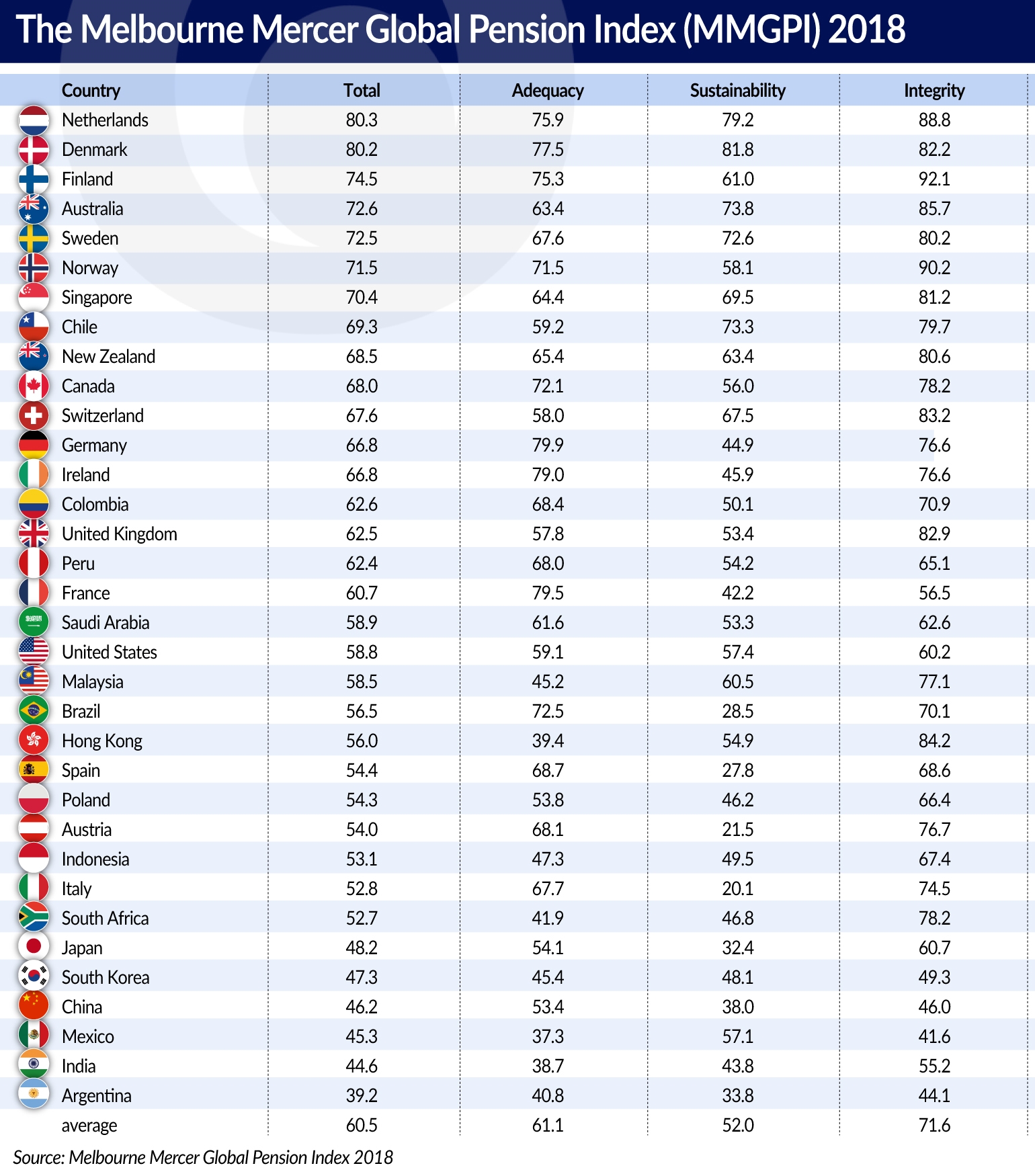

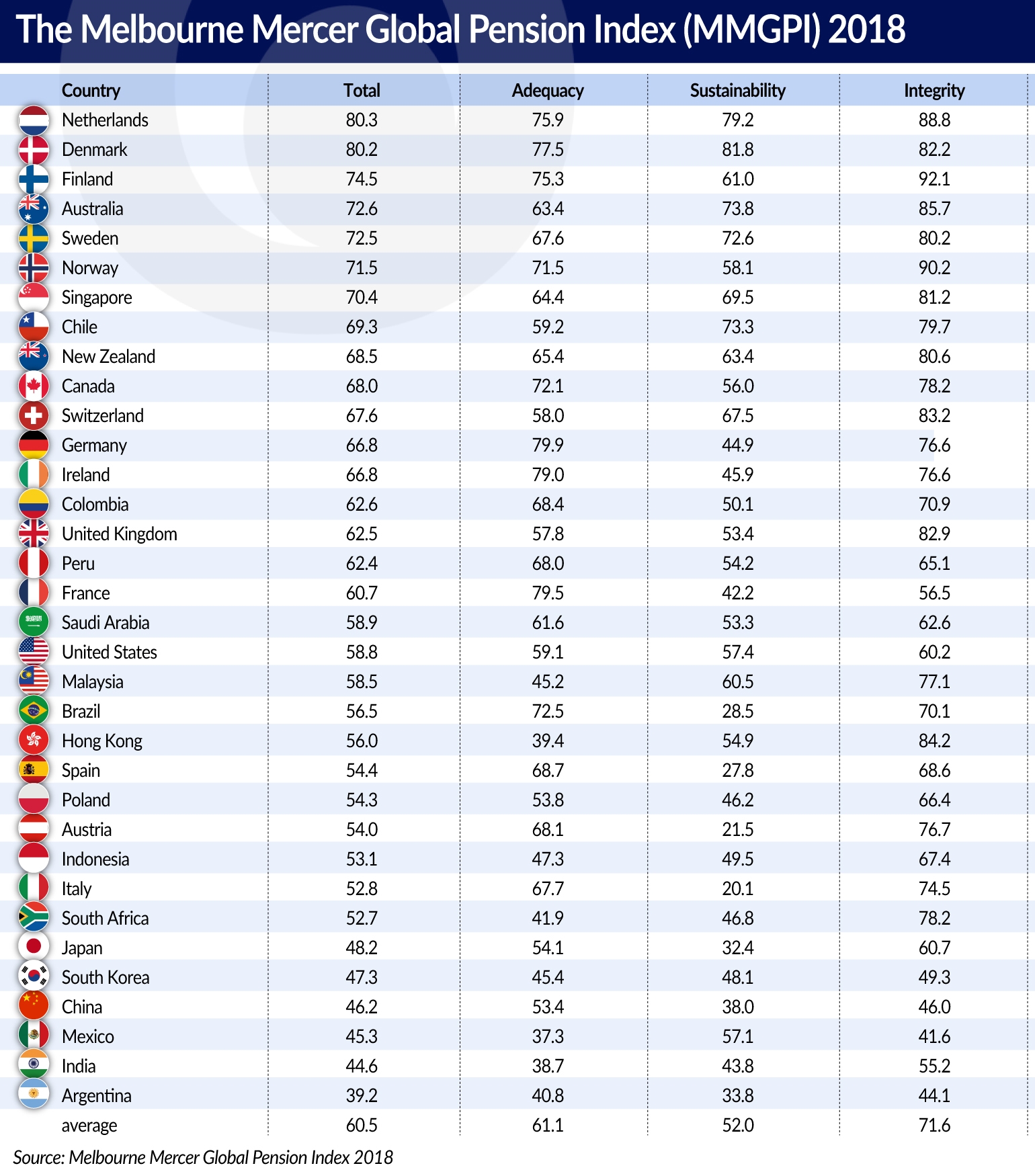

For the past ten years, the international consulting firm Mercer, which is involved in personnel consultancy, and the Australian Financial Services Center (ACFS), have been publishing the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index (MMGPI). The index assumes values from 0 to 100 and consists of three sub-indices: adequacy (the benefits for the retirees, the system’s design, the size of the savings, the tax support, the home ownership, the growth of assets), sustainability (pension coverage, total assets, contributions, demography, government debt, economic growth) and integrity (regulation, governance, protection, communication, costs).

In total, 40 different indicators are taken into account in the studies. Their main purpose is to compare the individual pension systems, to highlight certain shortcomings found in each system and to suggest possible reforms which would ensure more adequate retirement benefits, greater long-term sustainability and/or greater confidence in the private pension system. The studies cover 35 countries, including Poland.

There is obvious tension between the adequacy and the sustainability of the pension systems. The schemes that provide high pension benefits are often not sustainable. The trade-off between these two goals depends on the country’s social, economic and financial situation — both at present and in the long run.

In Europe, three systems (in Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden) have been positively assessed in terms of both adequacy and sustainability. All these countries have a multi-tier pension systems consisting of statutory pensions financed by the state from the contributions or from taxes, the employee pension schemes, and the private pension funds.

The statutory retirement pensions account for about one half of retirement benefits. Their amount is adjusted to match the condition of the budget and the situation in the economy. In the Netherlands, retired couples living together receive 50 per cent of the minimum wage, while pensioners living alone receive 70 per cent. The retirement age, which entitles people to receive the benefits, is gradually raised, and will be systematically adapted to follow life expectancy gains starting from 2022. In Denmark the retirement age is 67 years and will be raised to 68 years starting from 2030, with the possibility of further increases. In Sweden the retirement age is 65 years, but will be raised to 66 years starting from 2026. In 2010, an automatic balancing mechanism was introduced in Sweden, which determines the ratio of the system’s assets to its liabilities. As a result the stability of the Swedish pension system is verified annually.

When a worker retires, the Swedish government converts the balance in its hypothetical account into the monthly pension amount, estimating the average life expectancy of all employees born in the same year. The monthly payment is set in such a way that the balances of the hypothetical accounts are all exhausted during the average remaining life expectancy of all pensioners born in the same year.