(TPCOM, CC BY-NC-ND)

After the experiences of the last decade, and in particular the global financial crisis followed by the European debt crisis, in 2011 the European Commission (EC) introduced the macroeconomic imbalance procedure. This process involves an assessment of the degree to which individual member states meet the jointly adopted criteria.

The EC’s criteria for the assessment of macroeconomic imbalances are currently based on 14 macroeconomic indicators divided into three groups: the indicators of external imbalances and competitiveness, the indicators of internal imbalances, and the employment indicators. It also established thresholds for each of these early indicators of imminent crises. If the thresholds are exceeded, this may indicate the build-up of excessive imbalances in a given economy.

In order to obtain a more complete assessment of the risk of imbalances in the individual member states, the EC additionally analyses nearly 30 macroeconomic variables. Based on the conclusions from the data analysis, it identifies the member countries that should be subjected to an in-depth review.

Based on this analysis, the EC assesses the existence and scale of the imbalances and may — where necessary — issue appropriate recommendations for the given member state.

Slower rate of debt reduction

The Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure Scoreboard, published in mid-December 2019, covers the macroeconomic conditions in the EU member states in 2018.

The scoreboard indicates that the highest number of exceeded indicative thresholds is found in Spain and in Cyprus. In both countries five thresholds were exceeded, which was primarily due to excessive debt levels, and in Spain also due to the situation on the local labor market. Four indicative thresholds were exceeded in the United Kingdom, Croatia and Portugal. These results are better than in previous years.

More detailed analyses of the situation in the individual countries have been included in the EC’s report published along with the scoreboard — The Alert Mechanism Report. It indicates a general improvement in the macroeconomic conditions of the EU member states. At the same time, however, the authors express concern that the slowdown in the growth rate of the EU economy could inhibit this process. In particular, this could affect the rate at which the European economies reduce their debt levels.

A decline in inflation will lead to monetary policy easing, which will also weaken the effects of monetary policy stimuli on the individual economies. The willingness of governments to reduce debt could decrease along with lower interest rates.

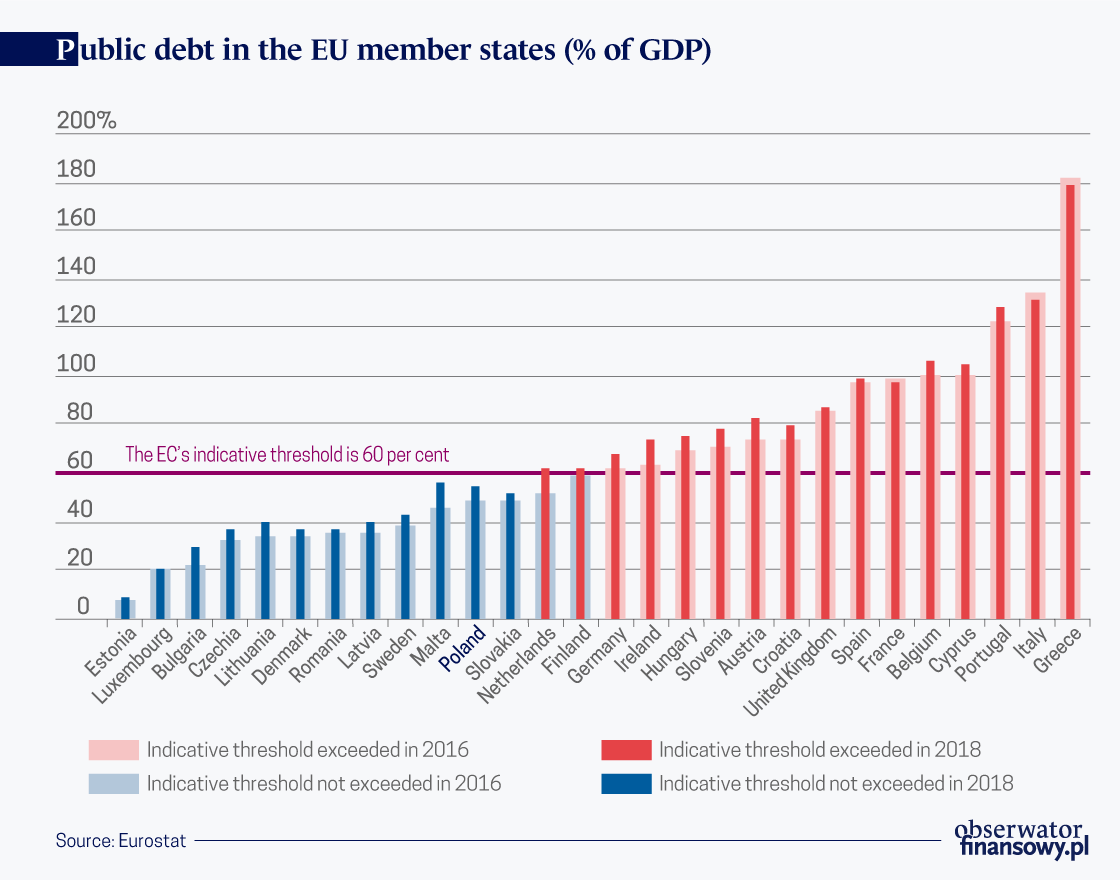

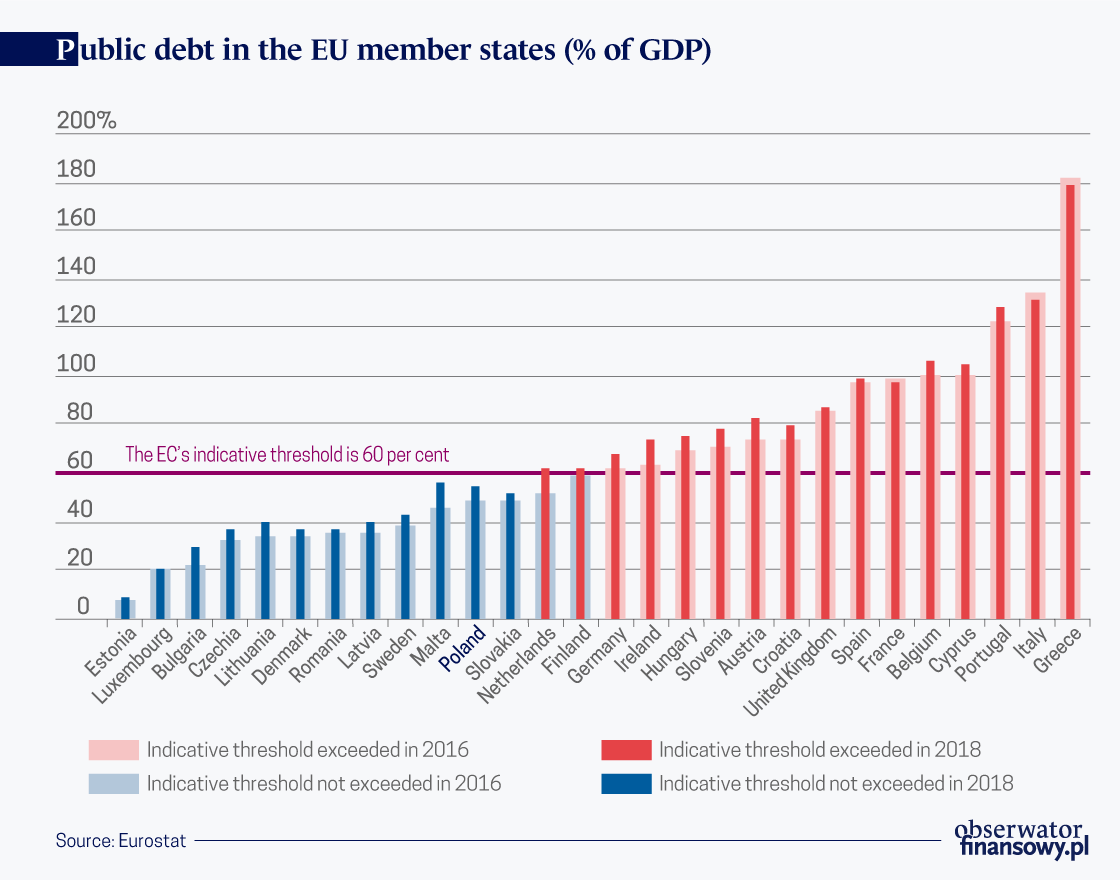

One key measure of macroeconomic stability is the level of public debt in relation to Gross Domestic Product. The debt-to-GDP ratios exceeded the threshold adopted by the EU (i.e. general government debt no greater than 60 per cent of GDP) in 14 EU member states (the highest number out of all the criteria).

In 2018, Finland managed to leave the group of countries in which this threshold is exceeded. The public debt in that country dropped to 59 per cent of GDP. For years, the worst debt-to-GDP ratios have been recorded in Greece, where the debt ratio is still increasing and reached 181.2 per cent in 2018 (compared to 176.1 per cent a year earlier).

The situation is only slightly better in Italy (a debt-to-GDP ratio of 134.8 per cent in 2018, which is higher than the year before) and in Portugal (a debt-to-GDP ratio of 122.2 per cent in 2018). Debt-to-GDP ratios of 100 per cent or higher were also recorded in Cyprus and Belgium, while France and Spain were very close to this level.

Poland is among the countries with relatively low and falling levels of public debt. In 2018, it dropped to 48.9 per cent of GDP from 50.6 per cent in 2017 and 54.2 per cent in 2016.

Focus on housing and labor costs

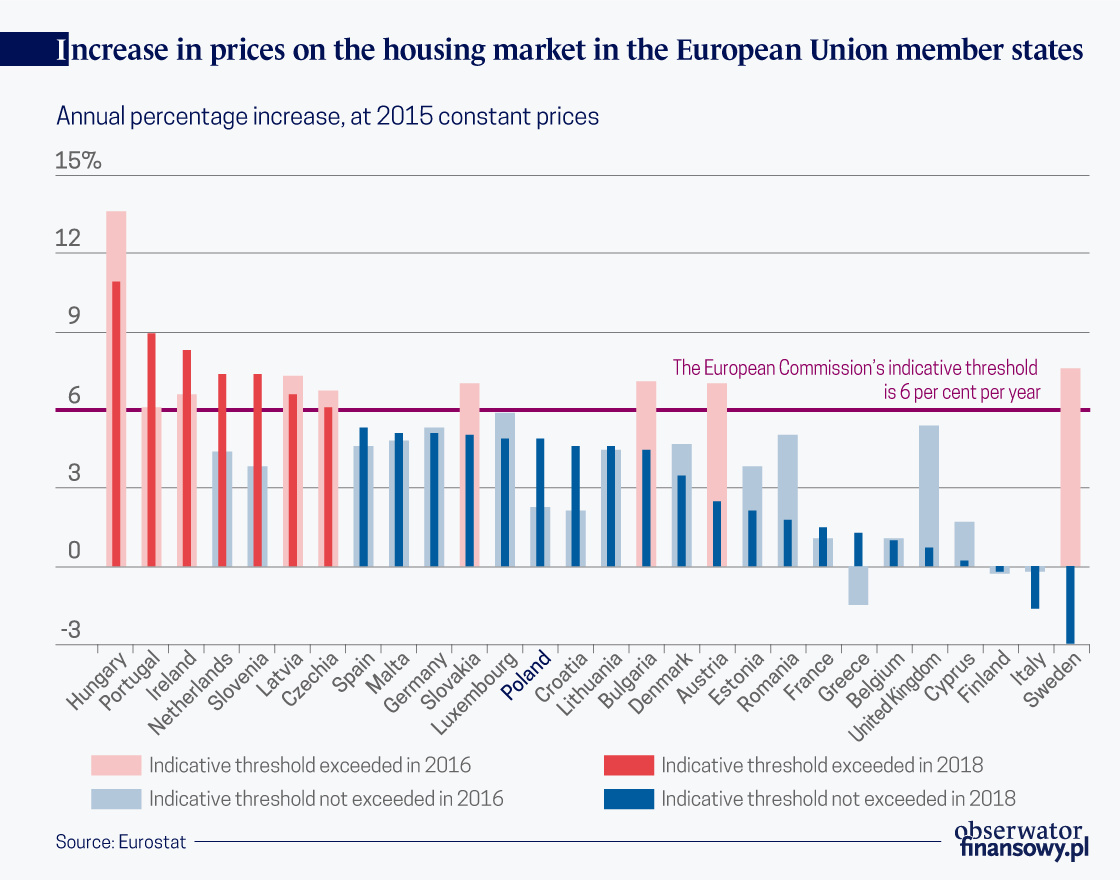

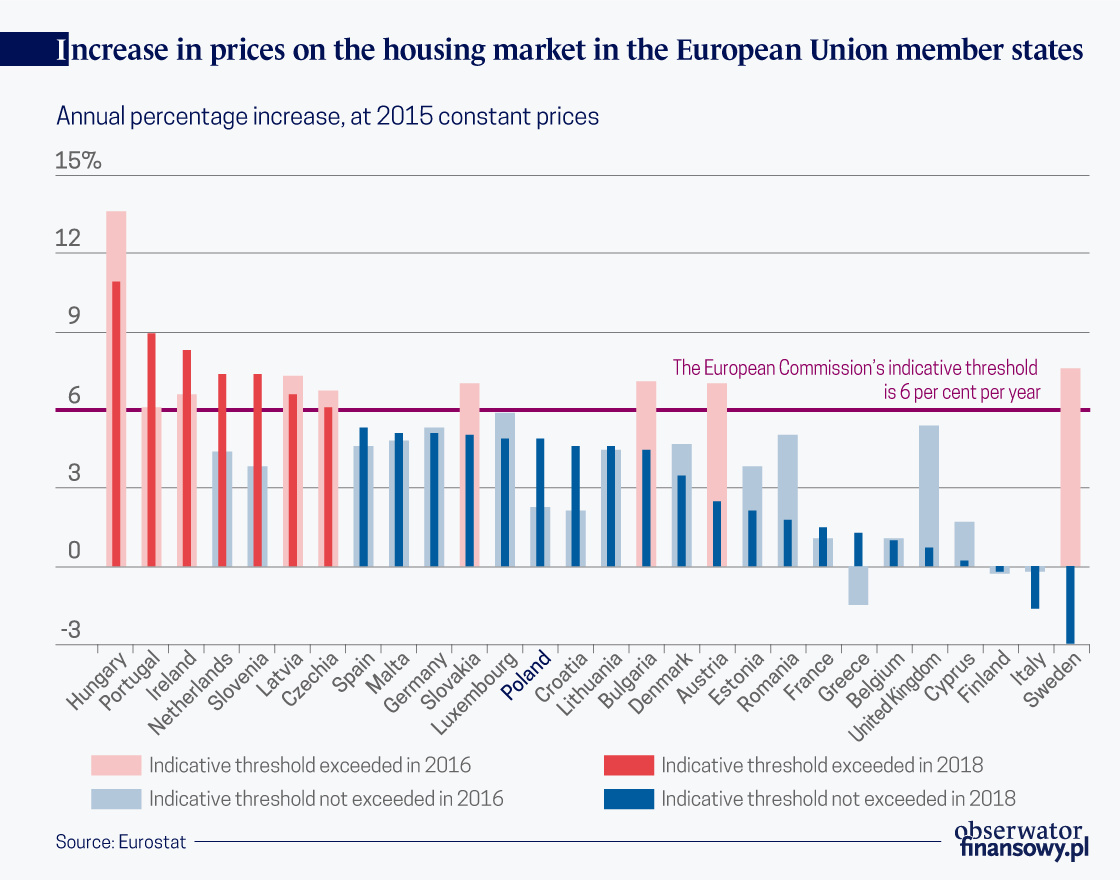

The EC’s report is devoted to the identification of possible future threats and is heavily focused on the condition of housing markets in the individual Member States. A decade ago, the boom on housing markets led to the outbreak of the financial crisis which initially affected households, followed by companies and banks, and ultimately also the public finances. Today, there is no risk of a crisis yet, but in many countries housing markets are already heating up.

According to the EC, this happens when the increase in the real prices of housing exceeds 6 per cent in one year. This threshold was exceeded, among others, in Hungary (an increase of 10.9 per cent in 2018), Portugal (increase of 8.9 per cent), Ireland (increase of 8.3 per cent), the Netherlands and Slovenia (both countries recorded an increase of 7.4 per cent in 2018).

According to the presented results, in Poland the prices on the real estate market increased by 4.9 per cent in 2018. This is less than the indicative risk threshold, but Eurostat data show that a clear acceleration is taking place in this area. The increase in housing prices in Poland reached 1.7 per cent in 2017 and 2.3 per cent in 2016. As highlighted in the report, the preliminary data for 2019, which are based on the results from the H1’19, indicate that the increase in property prices in Poland could exceed the designated threshold of 6 per cent.

Another area that the EC is currently focusing on are the changes in unit labor costs. It sees cause for concern if these costs increase by more than 9 per cent (over a 3-year period) in countries belonging to the Eurozone and by more than 12 per cent in countries outside the Eurozone.

The highest growth in unit labor costs was recorded in Romania (33.6 per cent), Bulgaria (18.3 per cent) and Lithuania (16.5 per cent). In Poland unit labor costs are also increasing, but not at a rate that would be alarming from the macroprudential point of view (an increase of 8.1 per cent).

Negative balance of capital

The only criterion of the macroeconomic imbalance procedure, where Poland exceeds the indicative threshold, is the net international investment position, i.e. the difference between foreign assets and liabilities of domestic entities.

Poland is not alone in this regard — about a half of the EU member states have too much liabilities towards the rest of the world in relation to the held assets. These are either countries particularly strongly affected by the financial crisis, and thus still heavily indebted, or converging economies that import capital from abroad.

Importantly, the net international investment position of Poland is improving with each year. According to the documentation published annually, back in 2016 the net international investment position of Poland was negative and amounted to 61.7 per cent of the country’s GDP. One year later the negative net international investment position decreased to 61.2 per cent, and in 2018 to 55.8 per cent of Poland’s GDP.

Based on the published reports, the EC will carry out in-depth reviews of possible threats in countries where it sees warning signs indicating the build-up of macroeconomic imbalances. These analyses will cover 13 EU member states: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Spain, the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany, Portugal, Romania, Sweden and Italy.