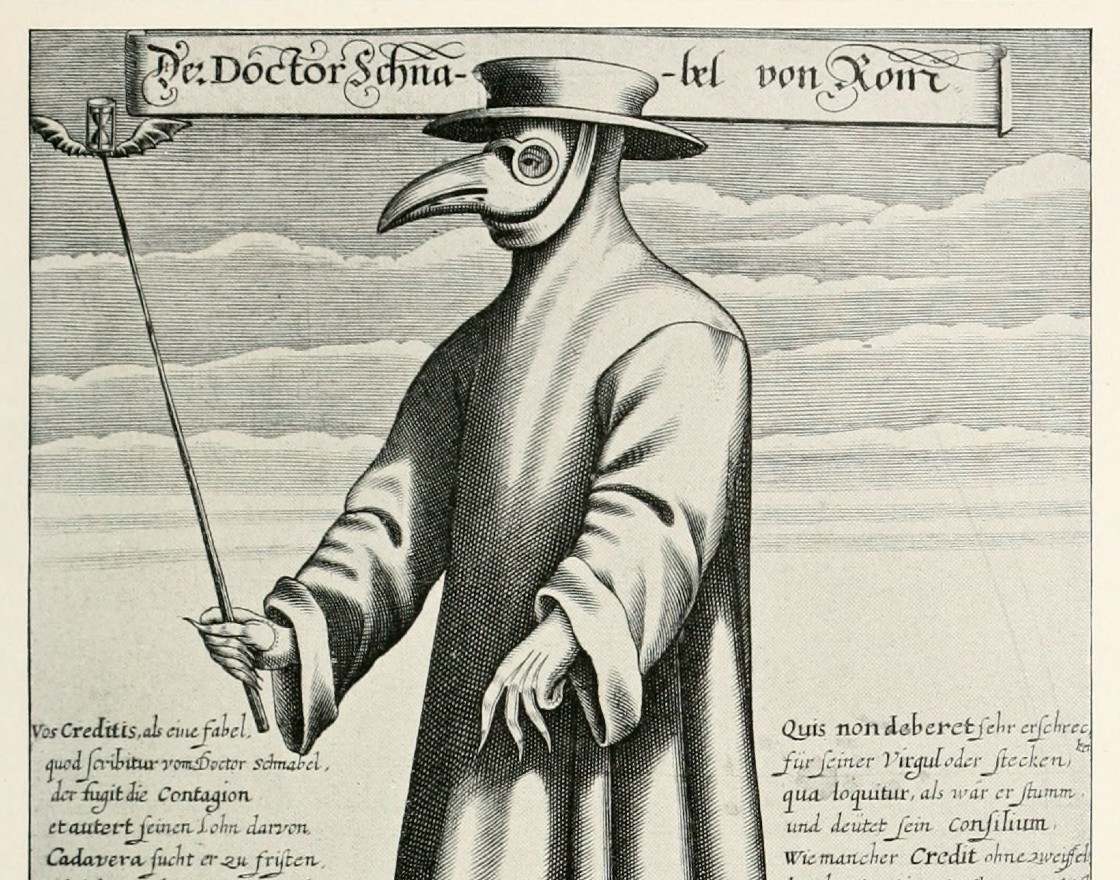

Rome, 17th century (Public domain)

There is no good reason to believe that anyone is able to precisely predict the consequences of the attack of the coronavirus, which has decided to inflict suffering upon humanity at this point in time. Things will turn out the way they will, but the future probably won’t be as bad as some fear. And it probably won’t be diametrically different from what we’ve known thus far. The world is developing and changing under the influence of thousands of impulses, and this or that disease is merely one of them, and usually not the most important one.

In the past it used to be different, but back then we did not know the aetiology of diseases, which allowed them to burn through populations completely unchecked. The effects were terrible, but there are some indications that they have been somewhat exaggerated. One example of that are the assessments of the total number of deaths from the pandemic of the bubonic plague, which spread through Europe in the years 1347-1351, after wreaking havoc in Asia, where it originated. Nobody carried out precise calculations of the numbers of victims at the time, and people always tend to exaggerate when they are afraid. As a result, the overall death estimates range from 75 million to 200 million victims in Eurasia, which means that the highest possible figure is almost three times larger than the lowest one.

Regardless of the number of victims, the consequences of the Black Death were profound and far-reaching, with the most important effect only occurring over 400 years later. This was the emergence of the labor market in England. In the aftermath of the pandemic, there was a shortage of labor in the countryside, so in order to protect the interests of the landowners, King Edward III resorted to the introduction of bans on the movement of peasants within the country and imposed laws prohibiting wage and price increases. This resulted in peasant revolts.

Over time mobility increased to previously unimaginable levels. The previous rigid social divisions started to become increasingly blurred, and the conditions were created for the emergence of what is currently referred to as the middle class.

The 14th century plague and the 19th century industrial revolution

We now know that the Black Death accelerated the decline of the feudal system and initiated changes that led England to the industrial revolution. The latter would have most likely erupted even without the plague preceding it by nearly half a millennium, but it would not have been the industrial revolution that we’ve come to know and learn about.

Currently, the media are full of grey-haired experts predicting the profound changes that are supposed to occur after the pandemic. Their voices are echoed by juvenile columnists presenting various extravagant visions of the post-pandemic world. The conclusion is that something really must be deeply wrong with the world, if both the old and the young are hoping for change. Of course, change will not occur from one year to the next, but once it comes, it will not be exactly what they would want it to be. Additionally, it is not the COVID-19 pandemic that will ultimately set the change into motion.

It just so happens that in the autumn of 2019, a historian from Yale published a book on the transformations of societies during times of epidemics, starting from the Black Death until the present day (“Epidemics in Society: From the Black Death to the Present”). The author, professor Frank Snowden, specializes in the history of medicine. He points out that a surprisingly large number of the ways in which we deal with plagues of infectious diseases were devised many centuries ago and have not substantially changed since.

Professor Jacek Wojtysiak from the Catholic University of Lublin, Poland, recalls that the first quarantine — that is, a period of 40 days of isolation — was ascribed to the biblical David, who went on to become the king of Israel. Snowden notes that such a long, forced isolation of infected and those suspected of being infected was repeated in 1347 by the citizens of Florence and Venice. This approach is still at the forefront of contemporary measures taken in the event of an epidemic. Although quarantines are now a bit shorter than they used to be, they often apply to the whole of society.

Contemporary physicians struggling with infectious diseases wear clothes resembling the outfits worn by astronauts. Back in the 14th century, medics donned clothing soaked in wax, and the drawings and paintings from that period often depict individuals wearing masks with long beaks. The beaks were not seen as a weapon against the grim reaper. Instead, they were filled with herbs in the belief that they would purify the miasma (poisonous air) before it reached the lungs. Although, the wax was somewhat effective, as it repelled the fleas which carried the plague bacteria.

Another common, and perhaps the most important element linking the distant past with the present, is the fact that epidemics are a catalyst for an increase in the popularity of the ruling authorities. Once upon a time this related to kings or princes, and today it remains true in relation to governments. When the death is staring us in the face, the restless masses need a stronger and more efficient authority, with its military, administrative, financial, and organizational capabilities.

Therefore, in medieval Florence, special health officers were appointed and assigned extraordinary powers to use force in order to combat the plague. They were the predecessors of today’s health ministers and heads of the epidemiological services. The authorities cordoned off (“cordon sanitaire”) the affected areas using force, violence, and terror. Most people remained healthy, but were overcome by fear, which meant that the political repercussions of such and similar actions were not a threat to the authorities.

It was much worse when the authorities were of a foreign origin. In the 18th century, in order to stop the next wave of the plague, the Austria used the army to cordon off the whole of the Balkans from the rest of Europe. A century and a half ago, the British returned to the idea of cordons in their attempts to stop the plague in India. It can be assumed that they were mostly concerned about their own interests and did not care about the fate of the natives, which is why the local residents feared the actions of the “white masters” more than the plague itself. This was not the most important cause of the outbreak of the self-determination movement in India, but its impact should not be overlooked either.

We do not realize that the 19th century reconstruction of Paris, which brought such stunning architectural and urban planning effects, had its origin in the concerns of Napoleon III and his entourage regarding the so-called miasmas, i.e. poisoned air which could cause another outbreak of cholera.

It was therefore concluded, quite rightly, that the city needed more ventilation and that more sunlight should enter its walls. As there was no city or regional conservator at the time, the authorities were able to proceed with the great demolitions, followed by the construction of new spaces, such as the Place de l’Etoile, renamed in 1970 as the Place Charles de Gaulle, as well as the wide avenues not found in any other city.

Over time, due to the fear of cholera and other diseases of the digestive system, the first hygiene and sanitation standards were introduced in residential housing and other areas of daily life.

Major changes in the labor market are unlikely

History reminds us that we shouldn’t be overly enthusiastic in anticipation of instant changes and rapid progress as a result of a sudden impulse. We keep hearing opinions that the coronavirus could contribute to a revolution consisting in remote work performed from our homes or — as many would prefer — from the beach. These, however, are the sorts of expectations that are never likely to materialize.

First of all, we are social beings, and limiting our contacts to household members would lead to the destruction of the family as the foundation of society. Looking from a very practical point of view, it is virtually impossible today to introduce remote work on a large scale in industry and in most service sectors. Office services only account for a tiny fraction of the global sector of services which cannot be provided from the home or it would otherwise be impracticable to perform in such a situation. On this basis it can be expected that take-away meals will not replace evenings spent at the restaurant.

The same is true in the case of education. Children love to be in the company of their peers. For them, staying at home for longer periods of time is torture. Thanks to the school system, which (usually free of charge) provides care for children and youths for a half of the day or longer, parents are able to work professionally. It also protects them from the mental breakdown which they would almost certainly suffer if they were forced to spend whole days with their offspring for a decade or more. Various new options, such as access to educational resources made available online, constitute a supplement to children’s physical presence at schools, and it should remain that way. However, this supplement should be both bigger and better. For example, we should expect the Ministry of National Education to provide significant subsidies to civic educational initiatives, such as a Polish version of the Khan Academy.

The idea of remote work comes with its own set of embedded problems. Just a few years ago, the banks did not send their first-line customer support employees to work from home. Instead, they simply made them redundant, passing all the activities related to bank transfers and other banking transactions onto the customers using online or mobile banking solutions. Such changes are not the result of viruses, however.

Long before the pandemic, I had the first-hand experience with a new — for me — example of transition towards remote work. This involved an insurance claim relating to vehicle damage. The representative of the insurer did not come to the garage in person. Instead, he sent a link activating a video transmission to my smartphone. Through the video connection, he carefully examined the damage and even took photographs. The partial removal of human presence from this process was motivated by the need or desire to reduce costs and to speed up the procedures in order to improve the competitive position of the insurance company.

The current environment of empty streets and crowds swept away from the palaces of consumption provides an excellent opportunity for all sorts of trials and experiments associated with the optimization of labor costs. For some professional groups, this sounds dangerous, but the pandemic will probably accelerate the implementation of new ideas.

The field where such progress is the most likely is online sales, which could possibly push hundreds of millions of sales workers out of the labor market. It is enough to refine the logistics of deliveries and returns, which could be paid for by the savings resulting from the downsizing of traditional commerce.

Migration as the last resort

For some time after the pandemic, the situation on the job market will be much better than we expect, because the entire world and individual countries will move with great impetus to make up for the losses after being forced to put their economic activity on hold. In the medium and long-term, however, there will be dozens of other currently unknown factors in play, which is why predicting the future is becoming as meaningless as telling the future by reading tea leaves scattered randomly inside a teacup.

At least for a few decades, the supply of labor will remain huge on the global scale. It is likely to continue to grow and will certainly not fall. The reservoirs of labor in Asia, Africa and Latin America are still full, and a withdrawal from globalization in what are expected to be peacetime conditions is simply not an option.

The Western world is a special case in this regard due to the prevailing demographics. Sooner or later, however, once labor shortages become more acute despite the ongoing automation processes, our fear of migrants will dissipate. After all, such fears were not shared by the plantation owners in the United States in the 18th and 19th century, by the Germans, who brought millions of guest workers to their country 60 years ago, or the British, who did the same thing 15 years ago. Any prejudice and fear of strangers in the West will ultimately lose to the desire to maintain the highest possible levels of consumption and comfort of life. The desire for economic emancipation, expressed by more than 6 billion people in the three previously mentioned poor continents, will also play a huge role in labor migrations.

Nursing and personal care for the sick and the elderly are an example of a sector in which migrants are widely accepted. The affluent European countries are already importing hundreds of thousands of care workers from countries such as Poland, Lithuania, Romania, and Bulgaria.

The same applies to physicians. As a result, OECD statistics indicate that from 2000 to 2017 the number of physicians in Poland increased by only 6 per cent in Poland, while in that time it grew by 30 per cent in Germany and the United States, by 40 per cent in Spain, and by 60 per cent in the United Kingdom. The situation with nursing staff is even worse. In Poland, the number of nurses increased by 2 per cent in the same period, while growing by 30 per cent in Germany and by 50 per cent in Slovenia, etc.

Economies rebound quickly after disasters

Once the pandemic ends, we can generally expect that attempts will be made to maintain or even extend the increased state control over society and the economy. Many will try to follow in the footsteps of Edward III and will not encounter any significant resistance initially.

Opposition will ultimately grow and will destroy the plans to strengthen the state’s role in the economy of the West. However, this will only happen after the people currently looking for the protection of the strengthened state once again come to the conclusion that the public officials — regardless of their rank — do not have any advantage in terms of knowledge, experience, management skills, or intellect over “ordinary” entrepreneurs and prominent businessmen.

History does not repeat itself, because it does not have to. It’s enough that it teaches us something. Great economic collapses were most frequently caused by wars. However, the annals of history are also full of descriptions of economic disasters caused by financial excesses. Thousands of wealthy people lost everything, for example, as a result of the tulip mania raging in the 17th century Netherlands. The 2008 crisis also had its roots in financial speculation.

The main rule is that after disasters and wars economies bounce back faster than after crises caused by human greed and the violation of basic laws of economics in the mistaken belief that “this time really is different”. Trust is the key factor here. In the case of natural disasters and wars, the reconstruction efforts are not hampered by the fear or even the conviction that our hard work will be in vain. We are not afraid that our efforts are pointless, because we can soothe our doubts by repeating that Vesuvius previously erupted two thousand years ago, and that the country which previously attacked us was militarily defeated and will never dare to repeat such action.

Thanks to economic historians from the University of Groningen, we know, for example, that the war-torn Italian economy grew by about 35 per cent in 1946 alone and made up for the wartime losses by 1949. In Germany, the war left an even stronger mark. Between 1944 and 1946, the economy contracted by two-thirds (66 per cent), but after that it grew by an average of 12 per cent annually for an entire decade. The Marshall Plan played a role here, but it was not the main factor in this economic acceleration.

In Poland, we also had three pretty good years, but after 1949 the Stalinist grip tightened and the good streak came to an end — the enthusiasm, or at least good intentions and organized work, were replaced by the “battle over trade”, as well as the rivalry with the United States’ military, based on steel mills and tanks.

In the case of financial and economic crises, we can always point out who bears the blame. In such a case, the reconstruction effort is much more difficult, because people are prone to think — quite reasonably — that those responsible for the financial excesses will soon return to power and will ruin everything once again. This can be described as the Sisyphus syndrome.

The economic collapse resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic will pass quickly, and perhaps even very quickly, because it is a crisis for which no one can be blamed. It is not wise to blame the Chinese for the real and alleged mistakes made in the first weeks of the outbreak of the pandemic. If the disease had started, for example, in the United States or in the United Kingdom, then, at least judging by the initial reactions in these countries, the course of the pandemic could have been much worse.

Some would like to believe that a momentous transformation is lurking just around the corner and that as a result of it we will stop producing and destroying the environment in pursuit of our increasingly exuberant consumption. Moreover, the only reason why such a change should occur is because we have finally realized that the purpose of life is not a never-ending party, but something else, something still undefined, but certainly much loftier.