Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

CC BY-SA Bromford/DG

The Demographic Reserve Fund was created 12 years ago, but currently it only has enough funds to cover pensions for three and a half months. Its resources could not even cover the deficiency of the state pension fund for a year, and the hole in the state fund grows larger every year.

“Poland’s demographic situation is very difficult,” writes the Central Statistics Office in its report “Information on the social-economic situation in the state for 2013.” According to the report Polish society is aging faster than previously predicted by demographic experts and many state institutions. The preliminary report shows that the retired group (60 for women and 65 for men) has reached the size of the youth group (under 18 years of age). Each group forms 18.2 per cent of the population.

This means that for every 100 citizens of working age there are now 29 retired and underage citizens equally divided. In the year 2000, 100 working citizens supported 40 young people and 24 pensioners, while in the early nineties the division was 50 young people and 22 pensioners for every 100 workers. In 1990 children and youth accounted for 29 per cent of Polish society and only 12.8 per cent were citizens over 60/65.

“When I say that ZUS or FUS will fail and go bankrupt by 2022 I am not exaggerating” says professor Krystyna Iglicka-Okólska, economist and head of the Warsaw Łazarski University, “By this time public finances will collapse under the demographic pressure and pension obligations.”

“The baby boom after the Second World War lasted a long time in Poland, about 11 years during which approximately 800,000 children were born annually,” Iglicka-Okólska explains. “These children will now become a crowd of pensioners. This in a time when less and less children are being born, and many young people of working age are emigrating.”

Iglicka-Okólska believes the only way to balance the financial equation in FUS is to lower the dues, to lower taxes and to free individual entrepreneurship.

However, according to statistics of the Polish Social Security Institution (ZUS), the fund’s biggest problems will come a decade later than professor Iglicka’s predictions.

“The date is not so important, we just do not have a demographic reserve,” says the head economist at Plus Bank. “We also don’t have where to draw it from. Additions from privatization revenues was a good idea for a while, but our privatization plans for the coming years show that this source is drying up. Another thing is that politicians cannot refrain from reaching into these reserves to cover the current state budget deficit.”

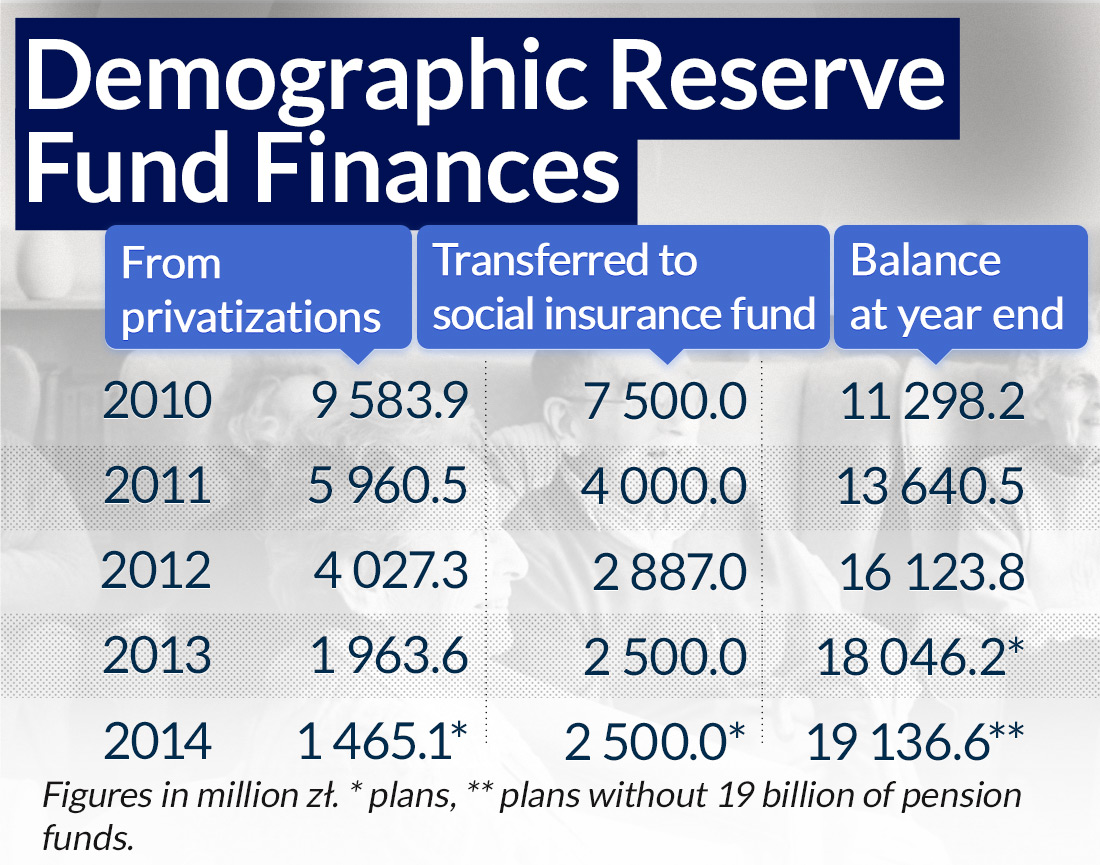

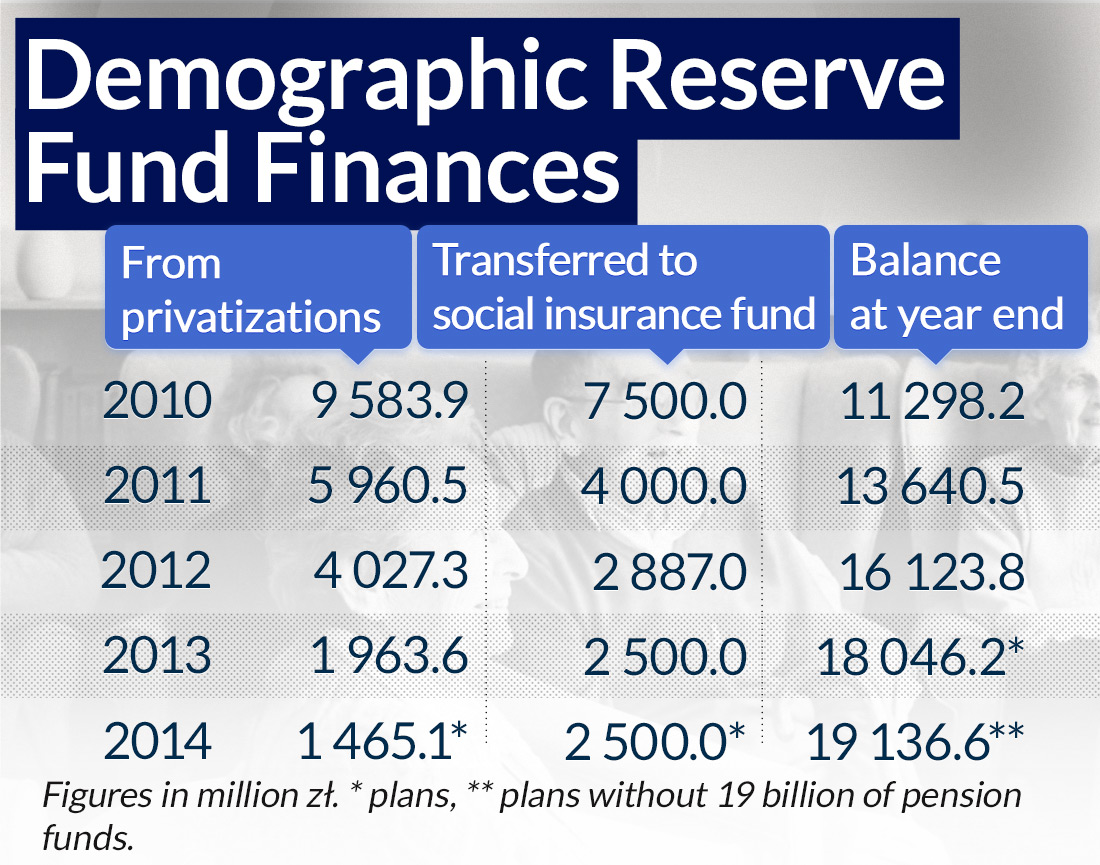

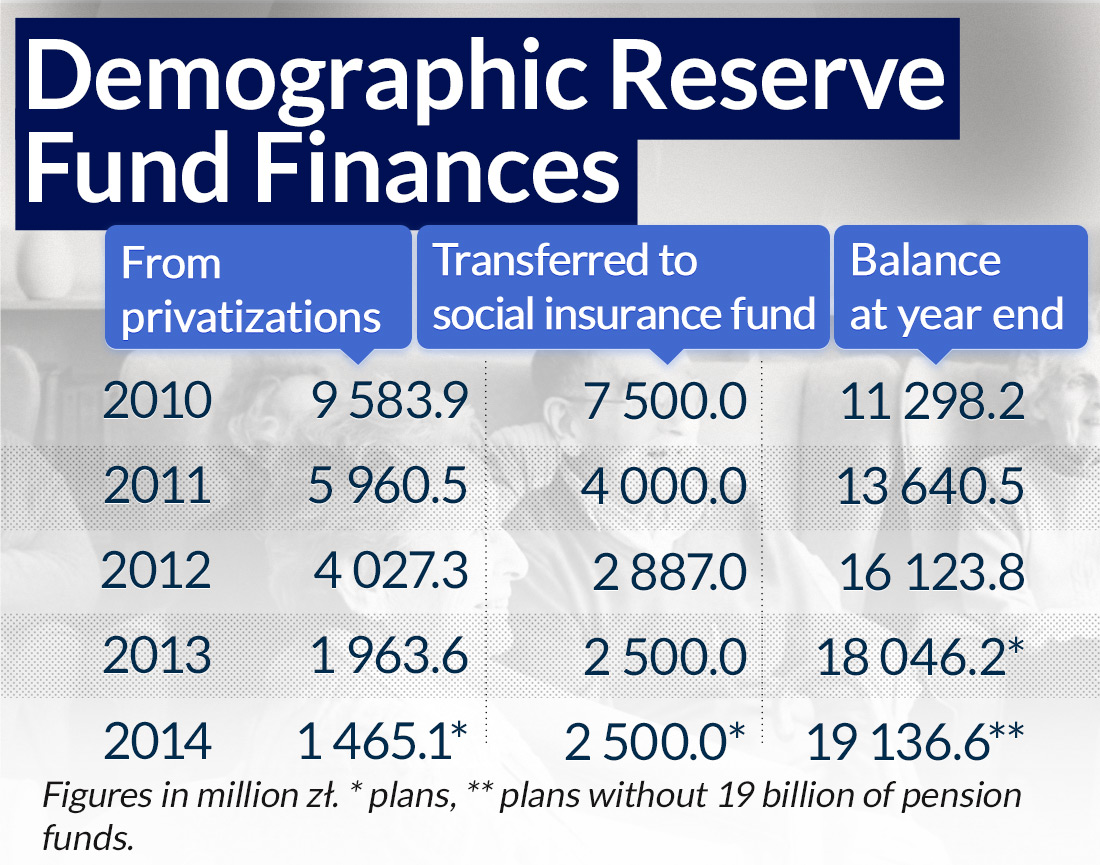

The Demographic Reserve Fund became the subject of much debate, when this year the government used it to cover a 19 billion PLN hole in the state budget. The fund was created 12 years ago. Deposits came from social security dues (accounting for approximately 11 billion PLN) from the privatization fund (approx. 21.5 billion PLN), and from investments in bonds and obligations (around 3 billion PLN). However, at the close of 2013 the fund held only 18 billion PLN because since 2010 approximately 16.9 billion PLN of the funds in the reserve were passed to the Social Security Fund (FUS) to cover current pension payments. Last year for the first time, the government took more money out of the fund then it deposited from the privatization fund. This year the situation will be the same: the state budget assumes FUS will get 2.5 billion PLN from FRD to cover current pensions, while deposits from privatization are set to be a billion short.

“The FRD will probably exist for another few years, as its more comfortable for the government to keep drawing from its reserves, rather than bother closing it,” comments Agnieszka Cłoń-Domińczak, lecturer at the Warsaw School of Economics and previously the Deputy Minister of Labour. “The FRD is being used as transit, we pay in and then we pay out again. It’s unfortunate that no thought has been given to the future and current problems with demographics and pensions.”

Deposits into the FRD also come from social security payments (currently 0.35 per cent of the payment). At first it was calculated that these deposits would end in 2008. But in 2009 the plan changed, deposits from payments were prolonged (this time with no end date set) and it was decided that 40 per cent of the gains from privatization would strengthen the FRD. In 2010 deposits from privatization were substantial; amounting to 9.6 billion PLN, but by 2014 the sum is expected to be only 1.5 billion PLN as plans for new privatizations are reduced. Since 2010 the FRD started to support the current FUS payments.

Recent comments by experts emphasize that until a balance of public finances is achieved, there will be no plausible possibility of creating a reserve fund to support future payments for the pension system.

“In our situation a reserve such as a hidden sack of copper or even gold coins is not the answer,” commented Tomasz Kaczor, head economist at BGK. “In our household finances no one really thinks they’ll take a loan now in order to have money for their retirement, or if they lose their job. But that is what the Demographic Reserve Fund looks like in a situation of unbalanced public finances.”

Marcin Mrowiec, the head economist at Pekao Bank confirms this point of view: that a real reserve can only appear with balanced public finances.

“That should be our strategic goal, instead of the current goal of having deficit below 3 per cent of GDP,” says Mrowiec. “As long as we have any deficit all “free” money (such as that hanging in the FRD) will be used to cover current needs. The problem is becoming a hugely important issue because a much larger demographic reserve, the Open Pension Fund (OFE), is being used and it is considered as acceptable for covering current needs. This buys some time, but unless we can achieve a balance then the deficit will once again reappear, and then what reserve will there be to draw from?”

Professor Iglicka answers that question, “There’s no doubt that the next reserve to be drawn from will be the OFE.”

The current situation with the FRD is a consequence of neglecting to fine-tune the specifics of structural reforms of the pension system in 1999. If that reform had been fully implemented (that is, if the possibility of taking an early pension was quickly limited, the age for men and women leveled, a rigorous system for granting sickness payments was introduced, miners privileges were not raised and a pension system was created for farmers), and if Poland had used the opportunity that joining the EU provided, then the needs of the social security system would be at least a third, if not half as small. As matters stand even the small successes of the 1999 reform have been diminished through fluctuations of valorization.

“We have been functioning with the problem of shortfall for some time,” says Piotr Soroczyński, the head economist of KUKE. “When we manage to pay for one thing, it turns out we can’t pay for something else. This is in part due to the fact that we’re trying to make up for our cultural and investment backwardness in the fields of infrastructure, or civil services.”

In comparison to these needs the FRD will always come last.

“Countries with a demographic reserve are those that have balanced public finances, and additionally have a feasible source of financing the reserve” says Soroczyński. “For example Norway, its reserve comes from sales of oil and gas, or Singapore’s budget surplus. Until Poland has such a source of revenue (it could potentially have from shale gas or copper) it will be difficult to support the FRD.”

What then is the answer to the FRD problem?

“Structural reforms,” says Wojciechowski, “but this can be repeated like a mantra.”

“We need to change of lot of things if we want to deal with the demographic pressure efficiently,” says Adam Antoniak, economist at Pekao Bank, with Marcin Mrowiec co-author of a report on the influence of demographic changes on Poland’s economic growth. Antoniak names a variety of essential problems “We need to improve family policy, confront the issue of emigration and health care, and look at all the things that increase work efficiency such as innovation, infrastructure, administrative efficiency, the ease of doing business.”

“If we can introduce effective reforms in all these areas, we may be able to decrease some of the demographic pressure,” says Antoniak. He also warns skeptics that “in 10 to 15 years people over 65 years of age will have a huge influence on politics, simply due to the size of this age group. The pressure to raise pensions will be huge and it will be an easy point for populist politicians to rally around.”

Time to introduce those structural reforms is running out.