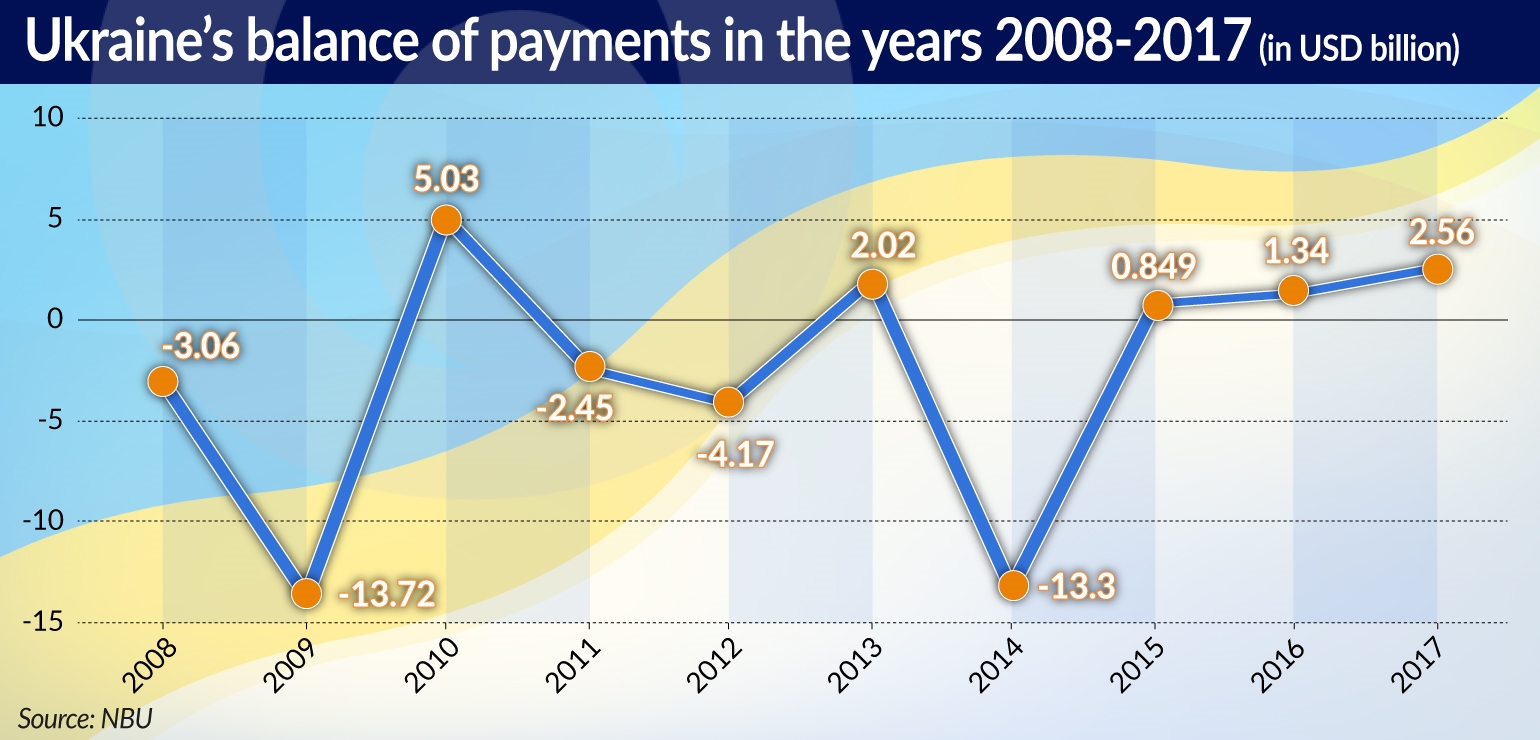

Following a sudden collapse in 2014, the Ukrainian balance of payments (BoP) was quite favorable for three consecutive years. This was not thanks to strong economic foundations, but due to the life support in the form of money transferred from abroad, now. However, the situation has deteriorated considerably, and economists are warning of another possible collapse.

Ukraine has already had it good

In 2014, Ukraine recorded the highest BoP deficit in its history — USD13.3bn. In 2015, Kiev had a surplus of USD849m. One year later it reached USD1.3bn, and in 2017 Ukraine achieved a BoP surplus of USD2.6bn.

However, according to forecasts by Moody’s rating agency, this year Ukraine’s balance of payments deficit could reach 5.5 per cent of GDP, with state-guaranteed debt at 72.3 per cent of GDP. The International Monetary Fund presented a slightly better assessment of the situation and in April announced a revised forecast for Ukraine for this year — according to that account, at the end of the year Ukraine will face a BoP deficit reaching 3.7 per cent of GDP.

According to data published by the Ukrainian central bank, the NBU, in March the current account deficit reached USD763m, i.e. 7.2 per cent of Ukraine’s GDP, while a year earlier it was much lower and amounted USD509m, which was an equivalent to 5.9 per cent of GDP. The NBU explained that this is the result of, on the one hand, the planned foreign debt servicing expenditures, and on the other hand, the negative balance in foreign trade and the increased dividend payments. In the Q1 there was a decrease in revenues from foreign investment — it up to USD296m compared to USD464m in the Q1’17.

As the NBU noted a slowdown in trade has been observed in March. Exports fell by 4.1 per cent compared to March 2017, while in February increased by 11.5 per cent (y/y). Meanwhile, imports continued to grow, though at a much slower rate of 0.7 per cent (y/y) in March, compared to 9.5 per cent (y/y) in February.

According to the data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, in the Q1 the inflow of funds to Ukraine, due to exports of goods and services, amounted to slightly more than USD13.6bn (9.1 per cent higher than in the same period of 2017), but at the same time Ukraine imported goods worth over USD13.7bn (11.3 per cent higher than a year earlier). As a result, the Q1 ended with a negative trade balance of USD135m.

In the opinion of the Ukrainian economist Alexey Kushch, the problems with the foreign trade balance are the main cause of the rapid deterioration of the situation with the country’s balance of payments.

“In recent years the balance was positive, and the current deficit recorded since the beginning of the year is a very worrying sign indicating the beginning of a new cycle of outflow of capital. In addition, very unpleasant tendencies in our foreign trade began in spring this year and the factors influencing them were external in nature and did not depend on our internal policy. It is true that the inflow of capital from abroad still almost compensates for the trade deficit, but we can already see the problems,” assessed Mr. Kushch. He pointed out that the main culprit was the fact that the prices of food which Ukraine exports collapsed on world markets.

Debt overhang

According to the Ukrainian Ministry of Finance, this year Ukraine has to repay USD12.5bn. Out of this USD8bn is an internal debt that the government can try to repay — at least in part — in the same way as it has been doing in recent years: by devaluing the UAH. However, as much as USD3.5bn is the foreign debt denominated in foreign currencies, which the government has to obtain for the purpose of repayment. In total, by the end of last year Ukraine’s direct and state-guaranteed debt exceeded USD76bn. In the years 2018-2021 it will be necessary to pay back as much as a third of this amount.

It is not clear how Kiev will obtain the necessary funds. For the past year, Ukraine’s cooperation with the IMF has been limited to meetings and talks. However, even if Ukraine managed to unlock this source of transfers, they would be much smaller.

“The tranches of the IMF loan that we were supposed to receive in the years 2018-2019 were reduced by 60 per cent, which means that the budget of Ukraine will have to allocate even larger amounts for the servicing of foreign debt. If the currency inflows from the IMF and the EU are reduced, it will be hard to service the debt. It will be necessary to take much larger amounts from the budget, which will lead to the suspension of increases in social benefits,” assesses Andriy Novak, the chairman of the Committee of Economists of Ukraine.

Officially, however, Kiev is still counting on support from the IMF. The NBU estimates that the size of the next IMF cooperation program may reach up to USD5.5bn, of which Ukraine would receive USD2bn this year. According to the Deputy Chairman of the central bank, Dmitro Sologub, who was quoted by Ukrainian news agencies, the much needed funds will be transferred in the Q3’18, although the bank official admitted that this is a purely “technical” assumption without any basis in the decisions on the part of Western financial institutions.

Just in case, the Ukrainian government is preparing an emergency programe — it wants to raise funds on the financial markets without the help of the IMF. “We plan to enter external lending markets without the IMF. This will be costly, if at all possible,” commented the Deputy Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko.

“In my opinion, these loans will be slightly more expensive than before. And their amounts may be lower than previously announced,” stated Yakiv Smolii, the Governor of the National Bank of Ukraine.

Supported by emigrants

For the time being, the most reliable source of foreign currency is the money transfers sent to the country by economic emigrants. According to the Polish central bank, NBP, in 2017 the remittances sent from Poland to Ukraine amounted to USD3.2bn. In 2016 the value of remittances amounted to USD2.1bn.

In the assessment of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), in the last year, all the transfers sent back to Ukraine by economic migrants amounted to approx. USD9-10bn. This was equivalent to approximately 8.5 per cent of Ukraine’s GDP.

The analysts of the Kiev-based think-tank, the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, compared these figures with the data concerning the top payers of a corporate income tax. It turned out that this amount is equivalent to the payments made in 2017 by a hundred of the largest companies operating in Ukraine, which account for 73 per cent of all tax revenues.

“If we take into account that a considerable part of the money of Ukrainians working abroad is spent on consumption, real estate and business, we can safely conclude that they are one of the basic factors reviving our economy,” commented Yuri Romanenko of the Ukrainian Institute for the Future.