Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Trendy gospodarcze

According to World Bank data, the share of exports in GDP (the so-called export rate) increased in Poland from one-fifth (21.3 per cent) in 1991 to a half (49.6 per cent) in 2015. The upsurge is even more visible in absolute terms. At current prices, in 1990 Polish exports amounted to USD17.1bn. Nowadays, it’s a value of a monthly exports. In 2015, Poland’s exports totaled USD236.4bn, and USD259.4bn a year earlier. The Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS) provides slightly more modest results, because it does not take into account the export of services and several other (minor) items. According to the GUS, in 2015 the export of goods reached USD200.3bn and USD222.3bn a year earlier.

Compared to the previous year, the decrease in 2015 was not a result of the collapse of demand or prices of Polish goods and services, but mainly a result of a strong appreciation of the USD against the EUR. A vast majority of Polish exports are settled in the European currency, whereas in March 2014 it was necessary to pay USD1.39 for EUR1, while a year later it was only USD1.05.

This explanation is confirmed in the PLN account. In this perspective, in 2014, Polish exports were worth PLN693.5bn, and a year later ‒ PLN750.8bn, and thus grew more than distinctly. According to preliminary data, in 2016, exports were already close to the mark of PLN800bn. It was PLN798.2bn, so it needed just „cents” to get to PLN800bn.

When comparing and evaluating data on foreign trade, it is important to note that due to different goods and service categories, exchange rate movements, currency structure of settlements, duty-free zones, etc., the discrepancies in statistics are to a certain extent natural and unavoidable.

In 2015, the value of exports per inhabitant of Poland amounted to USD5271.83 and if preliminary figures are confirmed, in 2016 it was as much as USD5607.74. As for such a short distance from nothing three decades ago it is quite a good result, but excess is not going to be a threat. Poland’s position in the world of exporting countries is well reflected by comparison of its results with Germany. In order to be on the top of the list, alongside the leader – Germany, Poland has approximately four lengths to go. There, the export per capita also reaches 20,000 but in USD, not in PLN.

Large exports of processed goods are a proof of Poland’s development rate. This is good because Poland exports much more than a quarter century ago, but at the same time it is not good or it is even bad, because Poland wants to earn as much as Germany. Poles want the German standard of living and state support, yet their offer will not have anything that beats a Mercedes, BMW, Audi or other German “delicacies”.

Poland sells a lot of low- and medium-processed goods, with small margins. The country make up for it with volume and tonnage. The subcontractor’s position is objective. It is a consequence of the miserable dowry with which Poland started to leave the zone of nonentity in 1989. Nobody had to „finish off” the industry of the Communist Poland, because it had been finished for years. The vocabulary used at that time is characteristic: in the official nomenclature of the Polish People’s Republic (the official name of the Communist Poland) there were no factories and enterprises, because instead of them there were „workplaces”, of which the primary purpose was employment, whilst the final product concerned only the director and the minister.

In a situation where domestic and eastern markets took all the lot, the quality, competitiveness and utility were not a major concern. The primacy of the sick ideology and overdone social function had therefore allowed selling to the so-called „West” mainly goods that could not be damaged after processing at domestic factories, primarily raw materials and materials (coal, copper, aluminum, sulphur, steel products), and agro-food products.

In the times of the Polish People’s Republic terms of trade were bad and very bad. If we take the year 1980 for a 100, then in 1985 terms of trade amounted to 95.7. By 2015, terms of trade prices improved by well over one fifth, because if 1990 amounting to 100 is the point of reference, terms of trade in 2015 were 122.6.

In 2016, terms of trade worked out very well and even great for Poland. According to OECD data, the measure for Poland was 103.72 and it was better than Germany (103.59), Czech Republic (101.62) and Slovakia (96.44), not to mention Russia (71.09).

After 1989, the belief of people who pinned their hopes on a market system and the state being pushed out of direct business came true. Current exports are almost deus ex machina, a phenomenon difficult to explain in the normal mode and sequence of events. No big program of outward expansion was developed, no exports development strategy was implemented, and exports continued to grow, though the so-called eastern market was decreasing and diminishing for a half of century.

The primary source of this growth was the economic freedom, the release of economic and trade initiatives, as well as the relatively good supply of raw materials and materials previously wasted by the so-called socialist industry. With every year, sales abroad increasingly became the specialty of small businesses, and then small and medium-sized ones. There was lack of native, large exporters and they are still not present, because behemoth exporters from the Polish People’s Poland are mostly and, fortunately extinct, and private young blood ones have not yet grown strong.

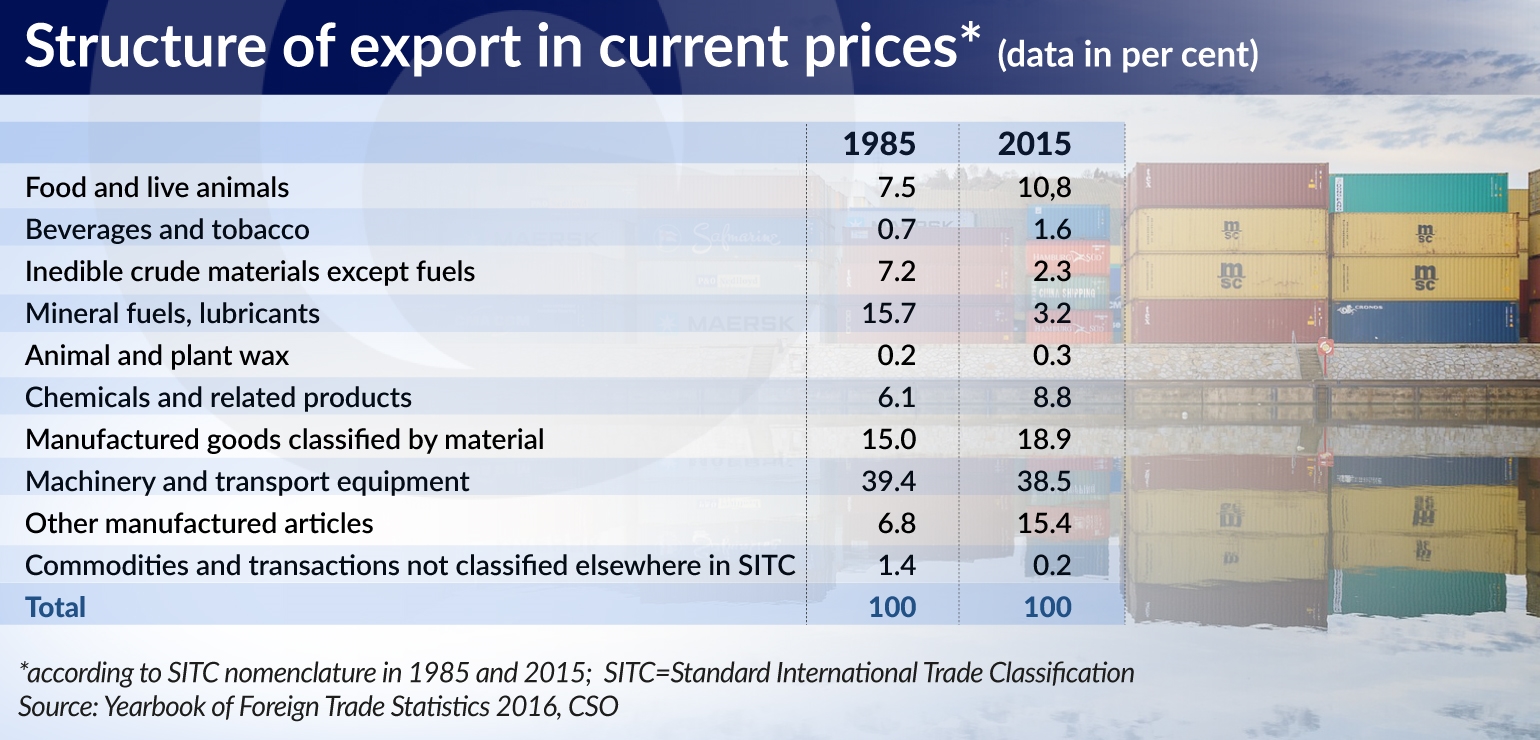

Changes for the better are seen in the overview tables of the export structure. Compared to 1989, the share of fuels fell by about dozen percentage points whilst inedible crude materials ‒ by several percentage points. The share of the so-called miscellaneous manufactured articles, produced predominantly by small and medium-sized businesses, has more than doubled.

An increase of the share of food in the structure of Polish exports is noticeable ‒ its share in the total value of exports has already exceeded 10 per cent. The condition for further and profitable growth in this segment is to stop overprotecting agriculture against taxes and contributions paid by other producers. Long-term subsidies are always associated with the waste and inefficient allocation of resources. The consequence of such a policy is a deterioration or even a loss of competitiveness of Polish agro-food products, and also indirectly by the remaining portion of the export offer. In the latter case, there is a mechanism that deprives industry of some of its resources that must be taken by tax authorities in excess to cover the shortfall of contributions from the agricultural sector.

Despite a relative simplicity of Polish goods sold abroad, the profitability of foreign sales is not bad. The terms of trade, which show the relationship between exports prices and imports prices, are positive, that is, Poland receives more money than has to pay for the unit of import.

Common sense would tell that if it is impossible to name a Polish industrial product that is a recognizable hit on the global market or even just a regional one, then there is some kind of trick behind the terms of trade. However, there is no trick, capital and structural realities are at work.

More than 60 per cent of Polish exports are goods manufactured by foreign, wholly or partially owned, companies. The role of Polish factories consists largely in the assembly of terminal equipment and machinery imported to Poland as subassemblies, components and parts. We export hundreds of thousands of cars, a lot of household appliances, but Poland is primarily a labor force.

The finished product is more expensive than its individual components, so terms of trade on macroeconomic level are advantageous for Poland. Financial gains on these operations are mainly derived by foreign factory owners, and Poland still has the benefits of the employees (wages) and the State Treasury (taxes). General benefits are also tempting ‒ after decades of mediocrity Poles are learning effective work and organization.

The role of European Union

The inflow of foreign investment capital involved in privatization and greenfield capital, which is destined to build factories from a scratch, on the scale of recent years, would have been impossible without Poland’s membership in the EU. Thus, without the EU, there would not be a huge part of Polish exports. Western companies would not transfer production capacity to Poland as a country of cheaper labor, because the precise supply chains would collapse on the EU customs border, which would then run along the Odra River, and not on the Bug River today.

Equally important and often more important is the unification of formal and legal conditions, the security of exchange and cooperation guaranteed by the EU institutions and courts. This is experienced by foreign entities active in Poland, but also by Polish entrepreneurs looking for markets in Europe, and beyond.

If Polish exports are driven by a four-cylinder engine, three cylinders operate on fuel provided through EU membership, and only one on the positive elements of our offer. A well-functioning Union is therefore in Poland’s interests, not standing back, when ideas of various speeds are budding, because when Poles plod along they are not catching up but losing. Polish membership should be intense so as to be in the vanguard of a good change in the Union, among which would be a review and verification of thousands of pages of regulations.

Domestically, Poland should be wary of the mirages of so-called industrial policy, i.e. providing support to the economy with money, plans and ideas born behind the ministerial desks. Countries that have managed to implement plans to build entire new sectors under state supervision can be counted on the fingers of one hand. These were the countries of iron social discipline maintained and enforced by dictatorial governments (Korea, Taiwan, China). In Poland, such miracles will not happen – it has a different, several thousand years shorter tradition and history of the state. On the other hand, there is still a chance of creating ever smarter conditions of management.