Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

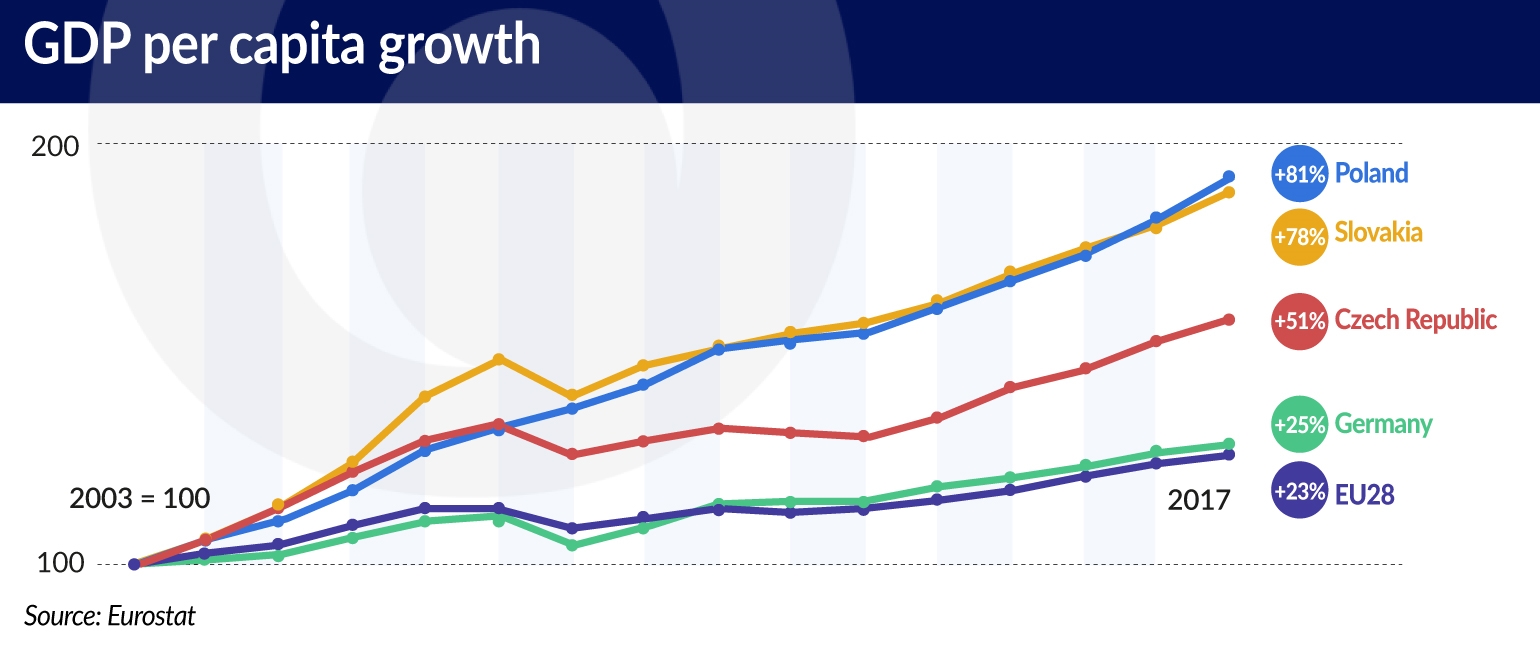

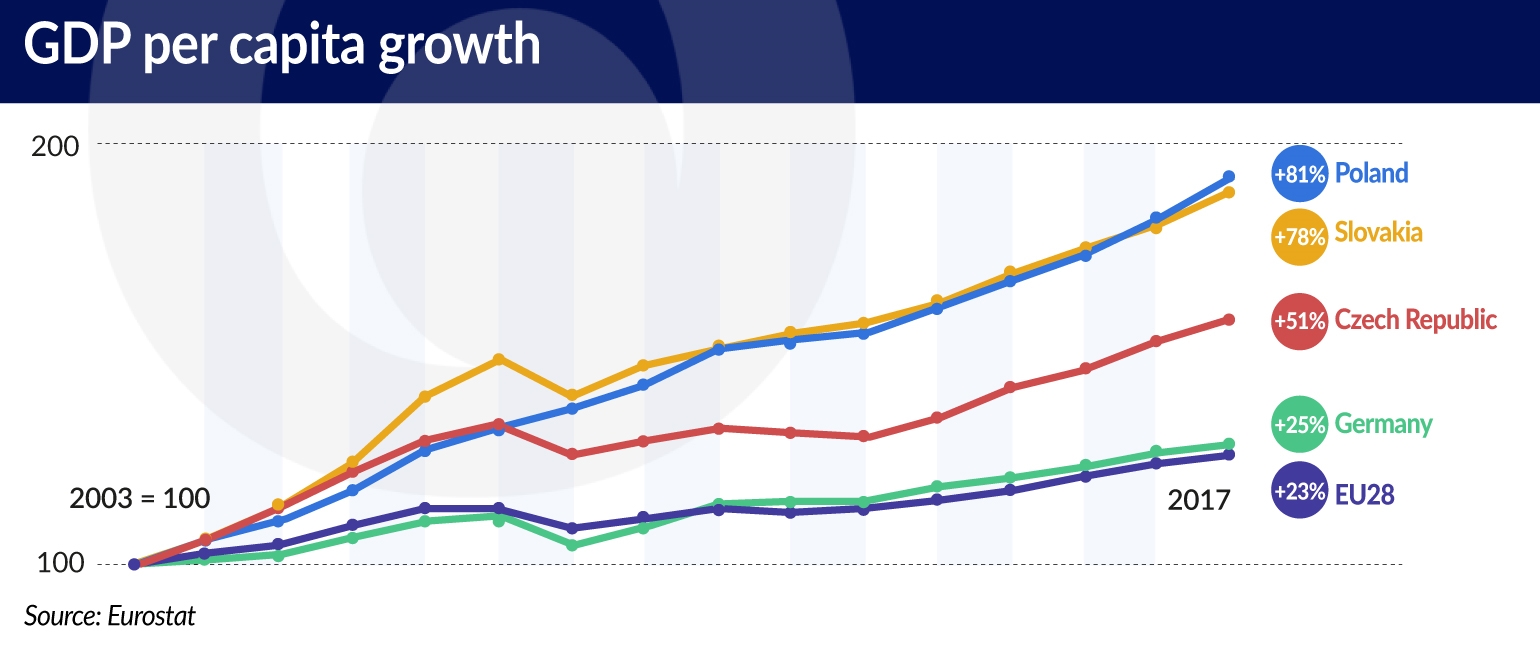

Through the support of the EU, Poland obtained funds equivalent to nearly twice the country’s annual budget. In 2018, Poland’s GDP per capita was 81 per cent higher than in 2003. The economy has one of the highest rates of growth in the EU, while the levels of earnings and assets of Polish household are slowly catching up with those recorded in the wealthier European countries. “In the next 15 years Poland can become one of the 20 largest economies in the world” wrote the experts from the Polish Economic Institute in the report entitled „15 years of Poland in the European Union”.

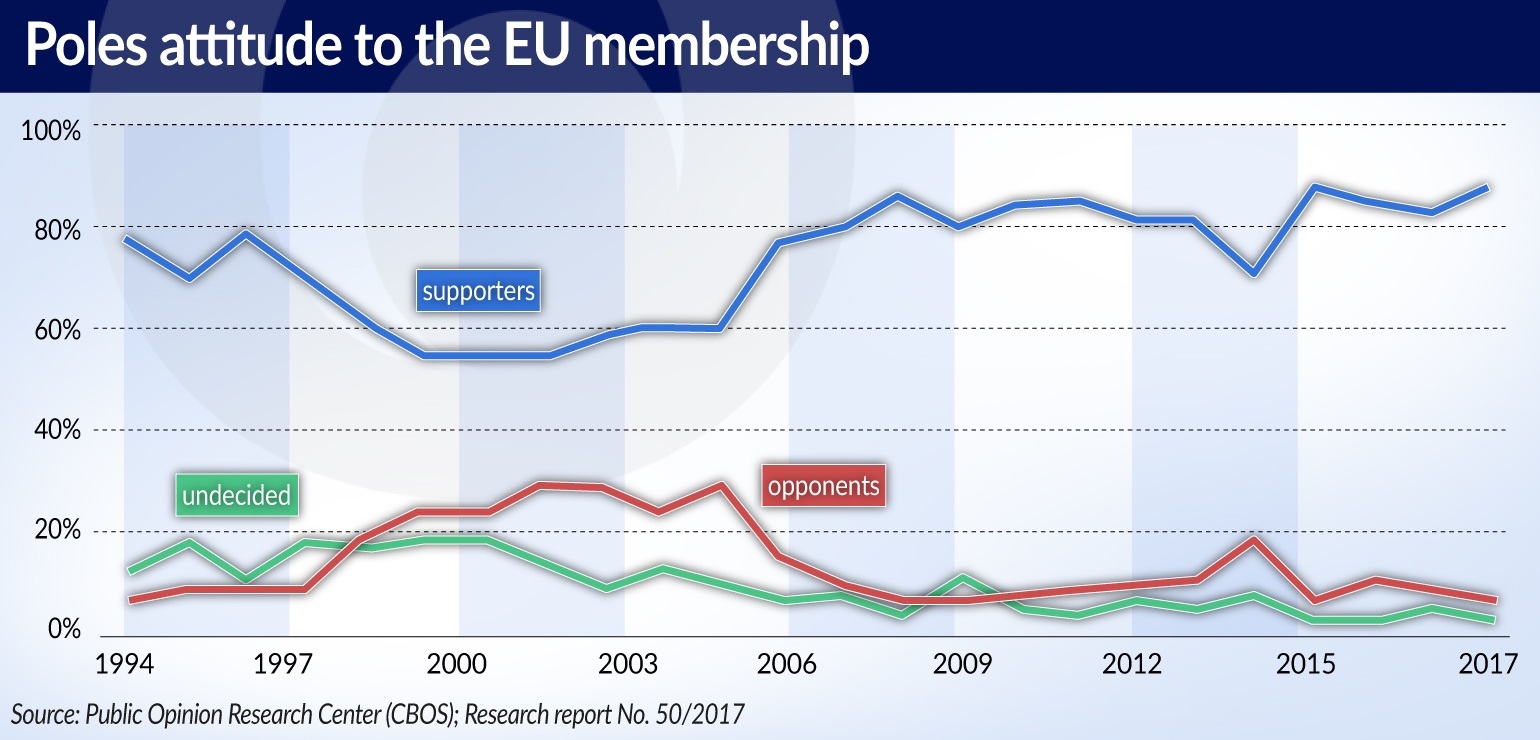

In order to realize what the European Union means to Polish people, it’s best to look at studies that show the overwhelming pro-European attitudes of Poles. The Center for Social and Economic Research (CASE) analysts point out in the report „Our Europe: 15 years of Poland in the European Union” that since Poland’s entry into the EU in 2004 surveys have consistently shown that a high percentage of the Polish people — fluctuating around 85 per cent — support the country’s EU membership.

Data from the European Values Survey (EVS) from late 2017 indicate that contemporary Poles consider themselves European: nearly three-quarters (73 per cent) answered that they feel a connection to the EU (and for 22 per cent of the respondents this relationship is very close). Almost half of the surveyed people trust the European Union (with 9 per cent claiming to have very high trust in the EU).

More importantly, the authors of the CASE report have pointed out that the respondents’ connection to the EU is not limited to declarations. Analyses of the available data have revealed that the sense of being European is associated with certain values supported by the respondents, and those values differ depending on how the respondents perceive Europe and Europeanness.

The economists from the Polish Economic Institute indicate that Poland has already received or will soon receive EU funding for a total amount of EUR164bn, which corresponds to nearly twice the country’s annual budget. “For us it was in a way like the Marshall Plan, and these funds have helped in the implementation of most public infrastructure investments carried out since 2004, including the construction of motorways, expressways or sewage treatment plants. When we evaluate our membership in the European Union, we shouldn’t forget about the harmonization of laws, the streamlining of financial flows or the elimination of numerous trade barriers,” points out Piotr Arak, the director of the Polish Economic Institute.

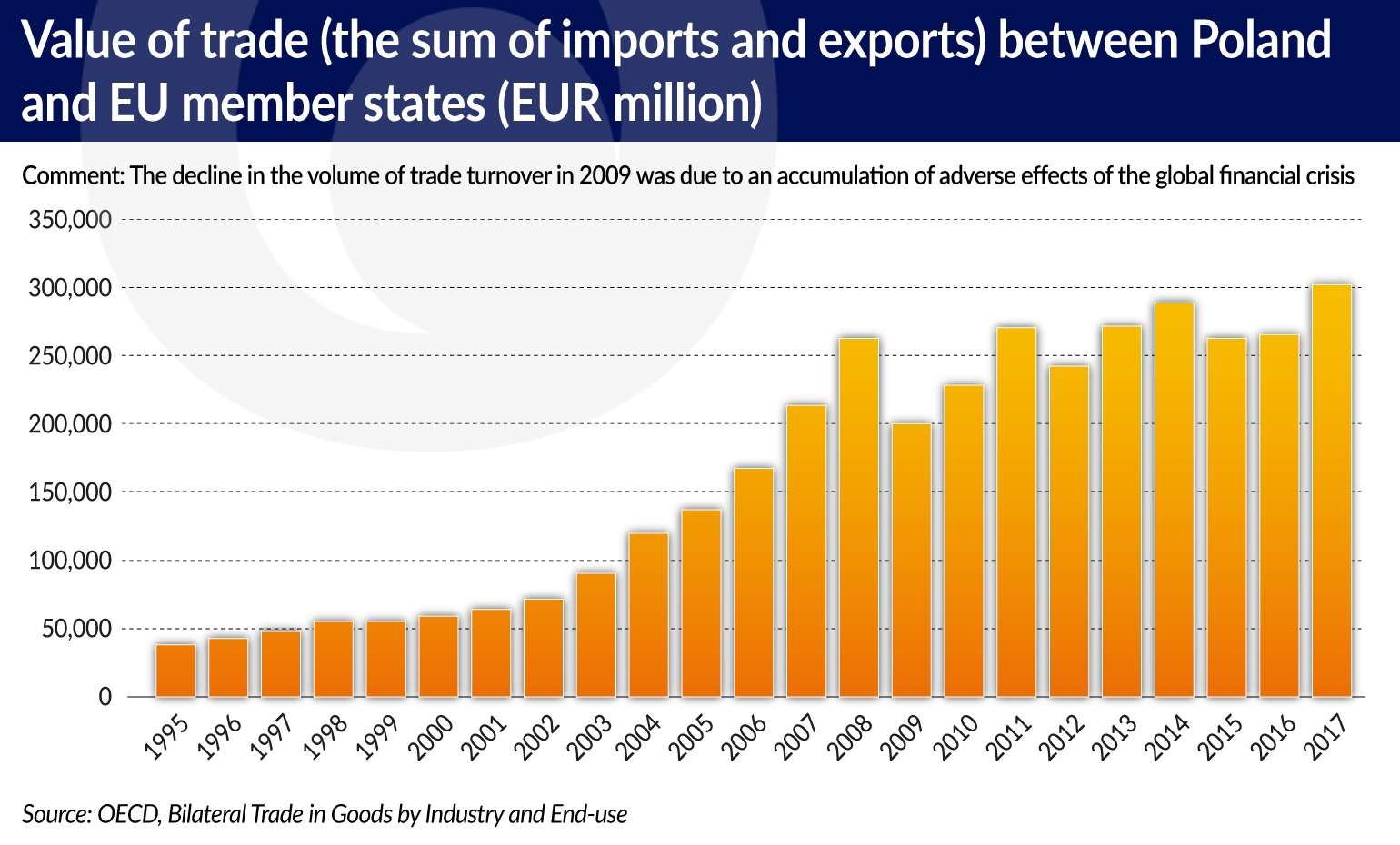

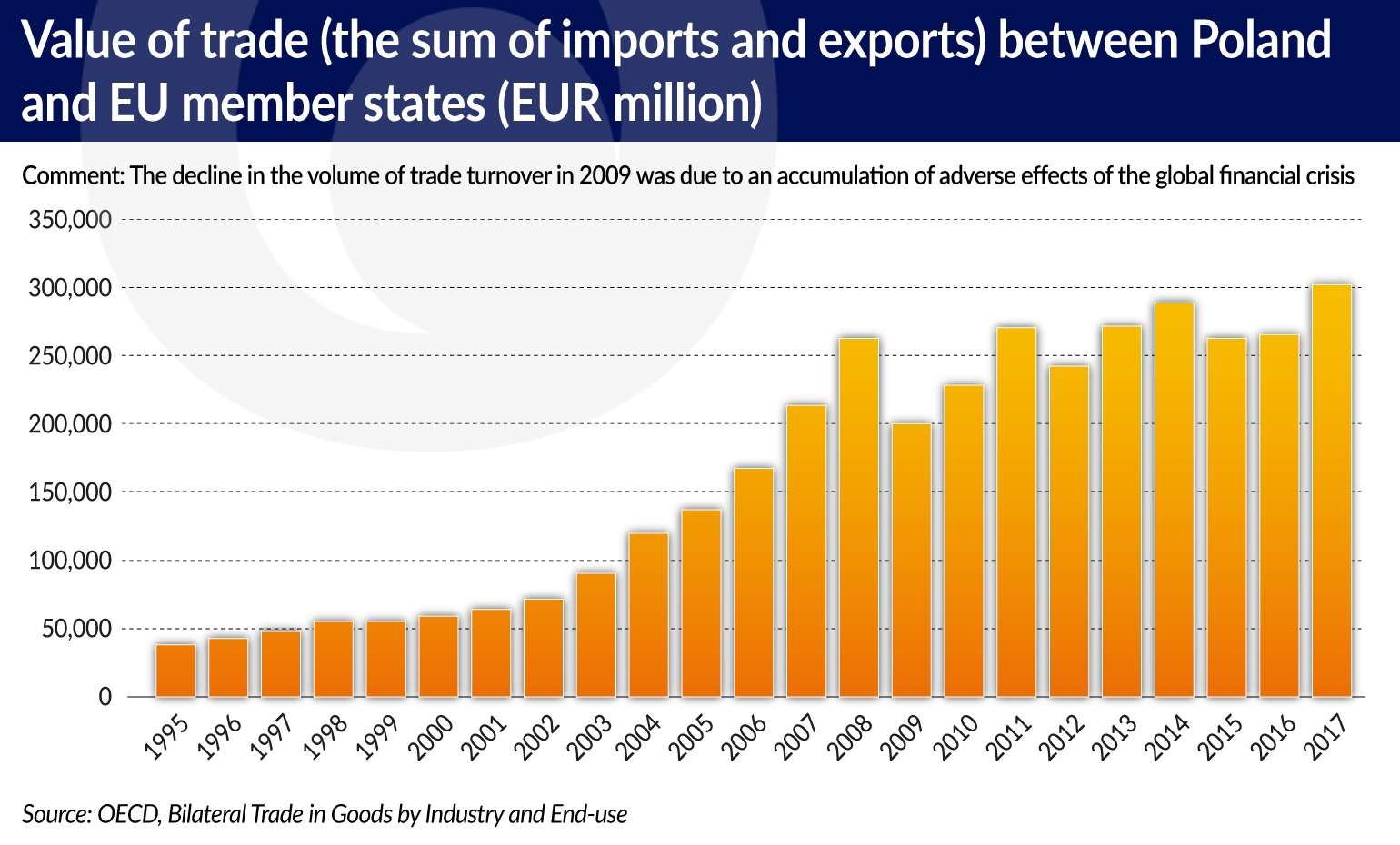

A rapid increase in trade has taken place. The value of Polish exports has exceeded EUR200bn a year. In the years 2015-2017, Poland recorded a trade surplus for the first time since the 1990s. The share of high-tech products in Polish exports increased from 3.3 per cent in 2004 to 7.7 per cent in 2017. Out of the EUR220bn worth of goods exported in 2018, about 80 per cent went to EU member states. “Germany currently remains our biggest trading partner, and Polish companies sell nearly 28 per cent of the exported production to that country,” explained Mr. Arak.

Another important step in the European integration came in 2007, when Poland joined the Schengen area. In a 2014 survey, one quarter of Polish people indicated that they had visited a country outside the EU, while almost one half of all respondents (49 per cent) said they had visited another EU member state. According to 2018 studies, almost one in four people (22 per cent) had either studied, worked or pursued training in another member state of the EU.

“The opening of the labor markets launched a new wave of emigration. According to British data, there are currently more than one million Polish people in the United Kingdom, up from about 70 thousand in 2003. Moreover, a total of 2.1 million Polish people were staying temporarily in all EU member states in 2017,” pointed out Andrzej Kubisiak, a labor market expert at the Polish Economic Institute.

Analysts from CASE point out that the geography of Polish labour mobility changed after the accession to the EU. Germany had traditionally been the most important destination for Polish migrants: according to the 2002 census, almost 40 per cent of them stayed there, followed by the United States, which accounted for 20 per cent of Polish migrants. However, by 2011 this migration structure had changed significantly: the United Kingdom became the top destination for Polish migrants (30 per cent of all migrants), followed by Germany (22 per cent), United States (12 per cent), Ireland, Italy and the Netherlands.

The breakdown of Polish migrants according to the destination country has been relatively constant over time, regardless of shocks such as the financial and economic crisis of 2008-2010 and the opening of the German labor market in 2011. At the end of 2017, the United Kingdom was still the most important destination (793 thousand people), followed by Germany (703 thousand), the Netherlands (120 thousand) and Ireland (112 thousand).

According to CASE experts data on the destination countries of Polish migration indicate the important role that Polish workers started to play on a number of European labor markets, especially in Ireland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Iceland.

„One result of the accession to the single European market has been a great increase in the diversity of products available in the stores,” reminded Jan J. Michałek, a co-author of the CASE report. He reminds that the effects of the functioning of the single market for the EU countries, including Poland, could be boiled down to a significant reduction of transaction costs, which has led to an increase in trade in goods and services and has contributed to a greater inflow of foreign investments. This, in turn, has increased the revenues of companies and the member states’ GDP. Additionally, the single market has increased the European Union’s attractiveness as a trading partner for third countries and has caused a significant rise in the diversity of goods available to consumers. This has also contributed to the creation of at least several million new jobs. The liberalization of the services market, which commenced in 2006, is only gaining momentum, but it is estimated that it could increase the trade in services by EUR33bn and create about 600 thousand new jobs.

There have been attempts to estimate the overall economic impact — in terms of changes in the individual countries’ GDP — of the participation in the European single market. These estimates indicate that the functioning of the single market has increased the prosperity of all EU member countries, except for Greece. There have also been preliminary attempts to analyze the subjective level of well-being, based on the results of surveys conducted among societies of the member states. This analysis shows that the subjective level of satisfaction of societies (which attempts to measure the quality of life) has grown due to European integration.

According to analysis of the American Chamber of Commerce in Poland, which has been cited by CASE, the Polish GDP in 2016 was about 2 per cent higher compared with a situation before joining EU. Consumption and investment per capita in Poland were also higher. It should be noted, however, that analyses of this type do not take into account the benefits from the inflow of budgetary funds or other effects (e.g. the labor mobility) resulting from European integration.

In practice, the free movement of capital resulted in an increase in capital inflows. In the first period of the EU membership, this was particularly visible in direct investment: the possibility of unrestricted movement of goods encouraged foreign investors to build factories in Poland and to include the Polish economy in the global value chains to a much greater extent than previously. These processes have resulted in the high overall efficiency of investments and Poland’s outstanding rates of growth. In the years 2007-2008, foreign capital financed the growing deposit gap in Poland. Meanwhile, the stable condition of the Polish economy during the global financial crisis attracted portfolio investments, which helped in covering the very large financing demands of the public sector at that time.

The analyses carried out by CASE indicate that Poland’s accession to the EU and the freedom of capital movement also had an impact on the financing of Polish households. Because of changes on the demand side (related to changes in the model of financing of large purchases), as well as the supply side (the opening up of the banking sector to the financing of households), household debt has increased the most since the accession. In 2017, household debt was more than 5 times higher than in 2003. For comparison, corporate and public sector debt increased approximately three-fold during that period.

It’s worth noting that although foreign financing played an important role in some periods, the share of foreign liabilities remained relatively stable, accounting for approximately one-third of the total corporate, public sector, household and banking sector debt.

EU membership has significantly improved the conditions for the functioning of the Polish agriculture. The economists from CASE point out that the consequences of these changes include Poland’s fast-growing positive balance of trade in agricultural and food products, as well as the absolute and relative improvement in the incomes of agricultural producers and inhabitants of rural areas.

However, the overall impact on structural changes in Polish agriculture is not uniformly positive. On the one hand, the membership in the EU, including the instruments of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), have contributed to the modernization and strengthening of the Polish agricultural commodity sector. On the other hand, however, research indicates that some of the tools of the CAP, and particularly direct payments to farmers, actually slowed down the outflow of land and labor resources from small farms.

The CASE report outlines that this slowdown is additionally reinforced by the individual countries’ reallocation of funds intended to support small and medium-sized farms, which is allowed under the CAP. Similar effects are achieved by domestic regulations in Poland, e.g. the exemption of the agricultural sector from income taxation, the preferential health insurance and social security schemes for farmers, as well as restrictions on trade in agricultural land introduced in 2016.

EU was crucial for the development of the Polish industry. According to CASE, the access to the European single market, the adoption of European norms, higher standards of intellectual property protection, and the possibility of establishing intensive cooperation with advanced companies within their value chains, have had two important consequences.

Firstly, these changes have led to a significant increase in trade volumes, and secondly, they have contributed to the absorption of new technologies and specialist knowledge. This has been conducive to an improvement in the quality of the domestic industrial production and a gradual increase in the share of complex products. Such changes bode well for the future of the Polish industry and of the entire Polish economy.

What are the challenges associated with the continued standardization of the European single market in light of the economic and social disparities persisting in the EU? Authors of the CASE report believe that issues such as the unfinished liberalization of the services market, the existence of so-called „social dumping”, and ensuring a level playing field on the single market are particularly important for countries such as Poland.

Moreover, benefits from trade exchange are the result of the differences between the individual member states, but it should be based on the principles of fair competition. In an era of increasing anti-globalization trends — especially in the aftermath of the global financial crisis — as well as rising inequalities, the re-emergence of statist economic policies, and the crisis of confidence in European institutions, any future discussions on the reform of the single market should necessarily focus on these issues. Poland can play an important role in these discussions as the largest member state from the region of Central and Southeast Europe.