Now, however, cracks are beginning to appear in this model due to the rapid changes that are exerting pressure on the Polish sector. This is why it is not unreasonable to ask what kind of a banking system Poland needs in the long term. The changes in the Polish sector are simultaneously influenced by both global and local factors. One of the most important global factors are, of course, the regulations that are being implemented throughout the world, but that is not all.

In 2015 experts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) created a model for assessing the positive or negative impact of the banking sector on the economy – the Financial Development Index (FD). According to this model, the Polish financial system is suited to the needs of the Polish economy as well as possible. The IMF study, conducted on a sample of 128 countries in the years 1980-2013, has shown that the development of the financial sector affects the growth of the economy, but the beneficial effects diminish or even become negative when the financial sector is over-developed.

The index was created on the basis of a number of variables, such as the universality of access to the financial sector and its effectiveness. It assumes values from 0 to 1, whereby a positive impact on the economy is observed when those values range from 0.4 to 0.7. For the Polish sector, the index assumed the value of 0.5 – the most optimal and “the best” among the surveyed countries. “I have the impression that the financial system has so far been driven by demand,” said Andrzej Halesiak, the director of the Macroeconomic Analyses Office of Bank Pekao S.A., during a discussion of “Club Poland 2025+” at the Polish Bank Association.

What is changing?

The IMF study was based on data from 2013. As lot has changed since then let us take a look at the most important changes that influence the Polish financial system right now.

In 2014 the “government bond” parts of the assets of the open pension funds were liquidated, which was followed by a substantial outflow of customers from the now-voluntary open pension funds. The introduction of the “slider” mechanism meant that more resources, allocated primarily on the capital market, were flowing out of the open pension funds, than the amount of new resources flowing in. This has led to a strong sell-off of shares on the Warsaw Stock Exchange (WSE). The return to the earlier retirement age from October 2017 could once again increase transfers from the open pension funds to the Social Insurance Institution, although the scale of this process is not yet clear.

The weakness and the post-crisis changes in the strategy of some foreign banking groups, which own majority of Polish banks, have led to a number of exits from the Polish market. Rabobank withdrew from BGŻ, General Electric withdrew from BPH, and UniCredit recently withdrew from Pekao S.A. Raiffeisen Polbank, and probably also Deutsche Bank Polska, are set to be sold as well. For now, there aren’t many investors willing to buy banks in Poland, because their valuation is extremely difficult.

One of the key factors for the valuation are the portfolios of mortgages denominated in CHF. Despite the higher instalment amounts caused by the rise of the CHF exchange rate, these loans have some of the best repayment rates. In this sense, they do not pose a risk.

The political discussion about solutions to this problem still continues, however, and carries such risk for the future. Although we can already see that extreme solutions will not be applied in this case, it is still not clear what costs associated with the possible forced restructuring of the CHF denominated mortgages would be incurred by the banks.

“This portfolio could generate systemic risk in the context of some regulatory solutions proposed in the public debate,” wrote Poland’s central bank NBP in the “Financial Stability Report” published in June. The authors of the report added that this risk casts uncertainty over the lending prospects, as well as the scale of burden on the banks’ financial results and, in the case of some, a burden on equity.

At the same time, due to the large share of CHF mortgages in the portfolios, the Polish Financial Supervision Authority ordered several banks to raise their capital ratios. And so the total capital adequacy ratio in the Polish sector increased at the end of 2016 to 17.7 per cent from 13 per cent in 2012.

The profitability of the Polish banking sector, in an environment of the lowest interest rates in history, has been declining with each passing year. This is happening under the influence of the burden of higher contributions paid towards the safety of the system, also as a result of the bankruptcies in the credit union sector and cooperative banks, as well as the tax on banks’ assets.

At the end of last year, the return on equity (ROE) rose to 7.8 per cent, compared to 6.6 per cent in the previous year, but this happened because of one-off transactions. At the end of H2’2016 the average ROE of European banks was 5.7 per cent. At the end of 2013 the ROE for the Polish sector was 10.1 per cent, while the average ROE in the EU was 2.7 per cent. The divergence is decreasing.

At the end of 2011, a well-known economist, Stefan Kawalec, proposed the idea of the “domestication” of Polish banks , i.e. increasing the share of domestic capital in the banks. Now the government is introducing the concept of “repolonization” of banks, which involves buying out stakes from foreign investors exiting Poland. The only buyers are companies with State Treasury shareholding, and therefore repolonization amounts to the nationalization of an increasingly significant part of the sector’s assets.

The studies do not provide clear answers

Despite the IMF’s studies and the large resonance of the FD index, the issue of the financial system’s favorable or adverse effect on the economy is still debated and studied. There are still no unequivocal conclusions, which could provide a basis for a consensus among economists. Besides, it is equally important to ask what sort of an economic system will be needed in 5 or 10 years, and this is a matter of strategic and not scientific discussions.

“The issue of what sort of a system is needed has been poorly researched. We talk about it looking at a snapshot of the present day, and not looking at trends or scenarios possible in the future,” said Jerzy Pruski, a former member of the Monetary Policy Council, now the vice president of Getin Noble Bank.

The relationship between the financial system and the real economy hasn’t yet been fully explored. It is also not clear whether similar interferences between the financial sector and the economy produce similar results in every country.

Małgorzata Iwanicz-Drozdowska, a professor at the Warsaw School of Economics, who is currently investigating the relationship between the development of the financial system and the growth of economies in Central and Eastern Europe, quotes the arguments of the economist Angel Barajas, who believes that the impact of the financial sector depends on the given country and its specificities. Other researchers, however, such as Seifallah Sassi and Amira Gasmi, came to the conclusion that loans to enterprises support the development of the economy, while loans to households harm it. Meanwhile, for the past several years in Poland, it has been household lending that has grown and increased in relation to GDP, while lending to enterprises has remained almost unchanged in relation to GDP for many years. “All of this requires further investigation,” said Małgorzata Iwanicz-Drozdowska.

Let us recall that the share of loans to enterprises in GDP rose from 16 per cent in 2000 to 19 per cent in 2016, and the share of loans to households grew from 10 per cent to 36 per cent in the same period.

How significant should banks be?

The advantages of a system oriented more on the capital market instead of the banking system, as in the USA, also hasn’t been proven. Andrzej Halesiak lists four different types of financial systems existing in the European Union, from the most highly developed and most market oriented, as in the case of the United Kingdom, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, to much less-developed (where the ratio of the assets of the financial sector to GDP is below 200 per cent) and mainly oriented on bank financing.

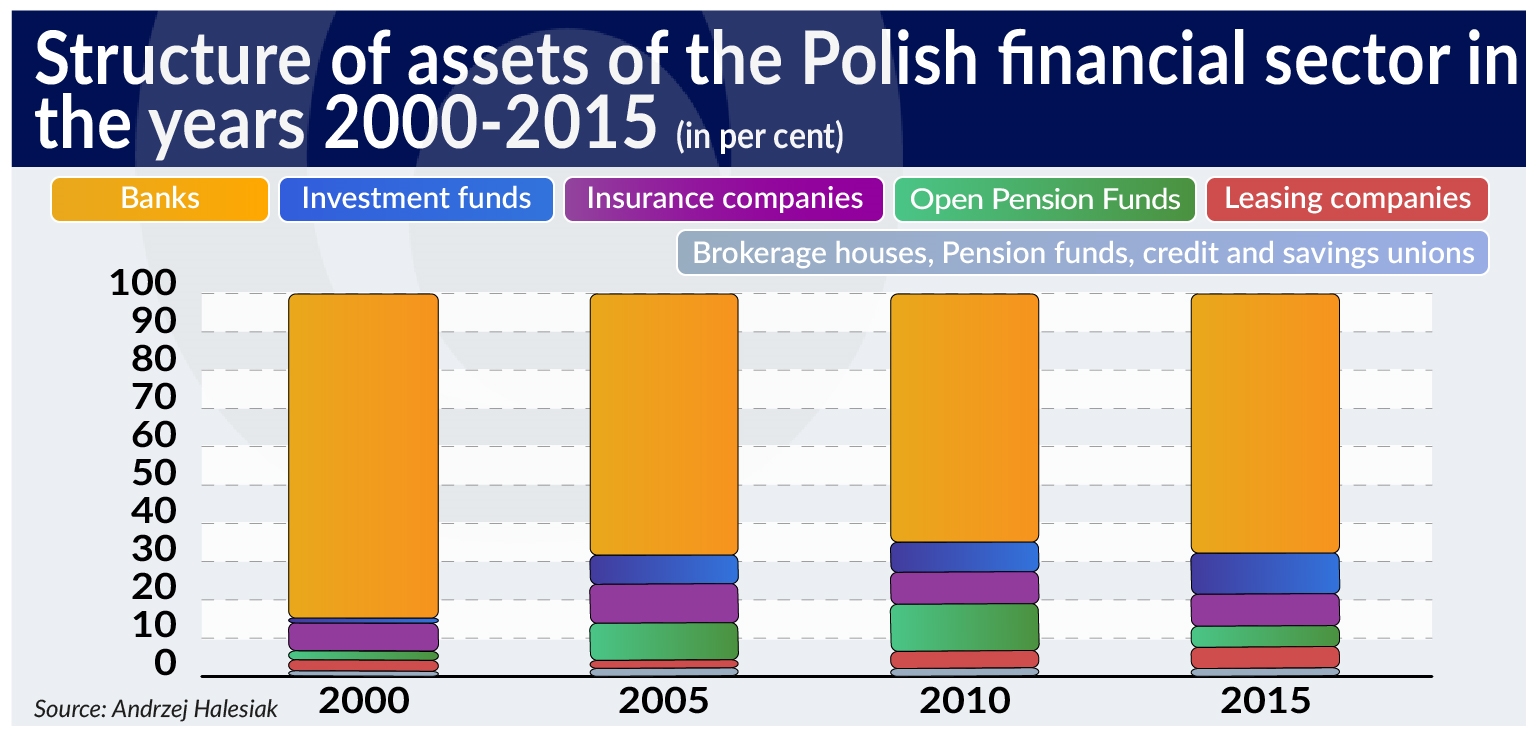

In Poland the assets of banks account for 68 per cent of the assets of the entire financial sector (excluding NBP). However, back in 2000, i.e. when the pension reform has just started, they accounted for as much as 85 per cent. The partial liquidation of the Open Pension Funds allowed the banks to regain importance in Poland.

Two years ago, the European Union launched a project of a capital market union aimed at reorienting the sources of financing of the economy from the banking sector to the capital market. This is because banks in the Eurozone are weak, in many countries have huge portfolios of non-performing loans (NPLs), and in 2013 the assets of the banking sector accounted for 274 per cent of the EU’s GDP. One strong argument in favor of such actions is also the fact that the capital market is able to disperse risk while banks are more likely to accumulate it in the balance sheets.

At the end of 2016 the assets of the banking sector in Poland amounted to less than 93 per cent of GDP, and loans amounted to 55 per cent, so one cannot talk about “overbanking”. The capital market, on the other hand, has been experiencing a decline in interest ever since the global crisis. According to studies conducted by NBP in 2014, only 4.2 per cent of Polish households held units of investment funds, and shares were only held by 3.5 per cent. Securities only accounted for 11.7 per cent of the total sum of financial assets of households, while deposits accounted for 68.2 per cent.

“There are no legal solutions that would modify the functioning of the capital markets in order to increase social acceptance for much more risky behavior,” said Jerzy Pruski.

Banks may determine or block development

Risk aversion after the crisis has been, at least so far, the immanent feature of the financial behavior of households. That is why Poles are choosing banks. Moreover, from all the institutions of the financial sector they enjoy the highest trust of the customers, which was strained by the crisis, but has been systematically rebuilt since.

Despite the pressure of global and local factors, the banking sector will continue to play a key role in financial intermediation and economic development in Poland in the foreseeable future. The question is whether it will drive or limit economic growth. What kind of structure and potential would be needed for that? “The role of the banking sector will not be reduced in the foreseeable future,” said Jerzy Pruski.

According to bankers and economists, the Polish economy and consumers need a fully diversified system. We need global banks, because they provide access to capital and financing of large investment projects that Polish institutions will not be able to manage due to commitment limits. We need those operating on a continental scale, since most of Poland’s trade is with the EU member states. Domestic banks are also essential, as they integrate the various segments of the economy: the local, the niche and the specialized fields.

“We need a banking sector capable of mobilizing savings on the domestic market and providing access to international markets. One that is able – when needed – to restructure companies and prevent exclusion, but also one that is internationalized. I think that for several years, or maybe a dozen years or so, this model of the banking system in Poland will continue,” says the President of the Polish Bank Association Krzysztof Pietraszkiewicz.

Unfavorable trends

Bankers are pointing out that some of the trends affecting the changes in the Polish banking sector could have adverse effects. The first one is that while the very well capitalized banks are stable, the raised security buffers limit their ability to create new assets. According to Andrzej Halesiak, while in 2012 the capital requirements allowed the bank to increase assets by 30 per cent, last year this reserve dropped to 12 per cent. “The surplus allowing for an increase of assets was consumed not by their increase, but by the increase of requirements, that is, buffers,” says Andrzej Halesiak. “It is a great challenge to look for a balance between the marginal increase in stability and the marginal growth of the economy,” adds Jerzy Pruski.

The falling profitability prevents the banks from raising capital. They can currently increase it only from retained earnings. But these profits are getting smaller and smaller. As a result, falling profitability hampers the creation of further assets, and consequently also limits credit provided to the economy. “Banking sector faces the structural problem of attracting capital when the alternative uses of capital are much more effective,” says Pruski.

Because of the tax on banks’ assets, last year the banks increased their portfolio of Treasury bonds, which are exempt from the tax, by EUR15bn, while the credit portfolio increased by EUR9.4bn. “A part of the sector is moving towards asset optimization,” adds Halesiak.

The departures of foreign banking groups from Polish banks, with their falling profitability and the risk associated with decisions concerning CHM denominated mortgages, are met with relatively low demand from foreign investors. As a consequence, consolidation is taking place in the sector, and the State Treasury is playing a leading role.

The consolidation of the sector leads to the risk of reduced competition and eventually higher costs for the customers, which, of course, could enable banks to achieve higher profitability. This is the structure of the banking sector in the Czech Republic and in Slovakia, where three relatively large banks dominate in each of these countries.

“We have a well-diversified banking sector and there is a risk that the situation will deteriorate in this regard as a result of consolidation and the deterioration of the competitive environment,” said Andrzej Halesiak.

There are at least two further risks associated with the increase in the State Treasury’s stake in the banking sector. The first risk occurs when we answer “no” to the question of whether state-owned banks will choose to provide loans to finance projects based on the assessment of their productivity. If this were not the case, it could deteriorate their profitability, and the ability to generate capital and increase assets.

The second risk is that in the case of perturbations in the sector, it is not private owners, but the State that will have to provide capital to the troubled banks. This happened last year when the Polish Development Fund acquired a part of the “emergency” share issue of Bank Ochrony Środowiska.

“The [Polish] sector could grow too slowly and then the contribution of the financial sector to the economy will not be utilized. The influence of the sector on the economy could be below the path that should be achieved,” warns Jerzy Pruski.