Iliya Lingorski: Accession to the eurozone is our priority

Category: Wideo

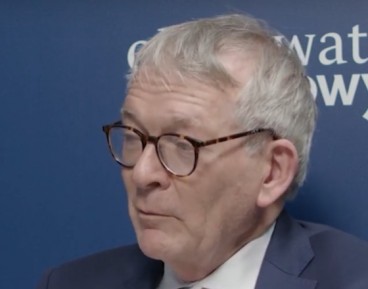

“Obserwator Finansowy”: You said that the euro area monetary policy is often asked to do too much. What do you mean by that?

Iain Begg: The trouble with monetary policy is that it can happen quickly. For the fiscal policy so as to agree it takes far longer. In cases of emergency monetary policy is left with the only option of how to deal with a crisis. We saw it in 2009, we saw it again during the euro sovereign debt crisis, and every time there is monetary policy they seem to be coming to the rescue because the political leaders could not agree on the appropriate fiscal response.

Is there any golden rule between a good fiscal policy and a monetary policy? Is it possible to create such a policy?

There have been examples of what has worked well. For example, in the 1970s the United States had very high inflation and into the 1980s you had very tough monetary policy and very loose fiscal policy. Reagan, in spite of being a conservative, was the president who led the fiscal expansion. At the same time, Volcker as governor or president of the Federal Reserve was having a tight monetary policy. The exact opposite in the US when Clinton and Greenspan were the appropriate agents in this. Clinton had a tight fiscal policy, Greenspan – a very loose monetary policy. That seems to work. It can work in a big economy like the US, but then you get the extreme counterexample. Unfortunately, in my country the United Kingdom, last year when somebody was British prime minister for a grand total of seven weeks in which time she managed to mess up the economy by trying to have a fiscal policy which was going in the opposite direction to monetary policy and the markets just said “No, you can’t do that” and that’s why Liz Truss and her chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng got into severe trouble.

What are the most effective fiscal frameworks? Can we indicate some rules?

Based on some work I’ve done recently, I’d say that we have very strong examples in Sweden, in Denmark and in the Netherlands. Because they have a combination of relatively mild fiscal rules but a longer term perspective, and they rely very much on what we call an expenditure rule saying not just what expenditure should grow at in one year but over the lifetime of a parliament. They negotiate that in a way which means everybody is certain about what’s happening and once everybody’s certain about what’s happening, it’s easier then to negotiate on particular components of the expenditure and find the way forward. But also there’re some unusual examples. It may not become an obvious one for Europeans. New Zealand has an effective fiscal framework and the key word they put on their website talking about the best ways to do it is one word: transparency. If everybody understands what everybody else is trying to do, that creates the framework in which things can work well. I think this contrasts with what I’ve been looking at recently which is the fiscal framework in the United Kingdom which I would regard as almost a joke. The current fiscal rule in the UK is that the net public debt should start to be falling in five years’ time. Now that is not binding at all, especially when in the next announcement they would come in and say “No, I don’t like it, I change it”.

You said that the fiscal policy makes sense only when governments are compelled to make hard choices. What do you mean by that?

They have to say to their spending departments “we have a total for expenditure,” and you need them to work out between you who gets what within that. You cannot do as, again to take a British example, Boris Johnson did when he was prime minister and say yes to everybody because if you say yes to everybody, the fiscal deficit and the debt get worse. So it’s a way of making the hard choices either for individual departments – you cannot have a new road, you cannot have this new hospital or something like that, but also between departments, saying health is a bigger priority than infrastructure. That’s a hard choice because everybody would accept you need both. But if the money is tight, you must choose between.

So it means that in fact it depends on policy, right? Because it is a moral choice what we follow.

Guest: Well, it’s moral choice but it’s also political choice because the government would typically come in and say “Here’s our programme for what we propose to do during the next parliamentary period,” but if they cannot do everything, they have to choose between priorities. So there might be priority one, in the current context in Poland is defence, we want to increase defence. If you’re taking money for defence, and not raising taxes, then you must by definition reduce money for something else. It’s relative, it’s not absolute reduction but it’s saying “where do you want to put the additional spending that we can raise”.

But can we say that there is a dilemma between – to make a long story short – investment and consumption?

It’s not as easy as investment versus consumption because consumption has a very broad meaning. In national accounts for example education is counted as consumption. But you and I would probably think: no, education should be investment. But the amount of spending on education in national accounting terms would go up and would raise consumption. By the same token, defence is investment what is investment in security, but it’s something which is seen as a current expenditure. Whereas, if you’re talking about public investment in infrastructure, then it’s clear that it is investment. So there’s a problem about the definitions within national accounting standards as well as the political purpose.

My last question concerns demography. Demography is a ticking bomb in Europe and sometimes we may perceive migration as a cure that is worse than disease. How will it affect us? Is there any solution to that dilemma?

There isn’t an easy solution because if you’re talking about an ageing population which most European countries are, you have this block of older people who depend on the working-age population. And the working-age population can grow either by activating more people or by using some form of immigration to increase it. It’s quite simple in that respect, but if you want to cut the expenditure on the non-working population, particularly the ageing population, then you have to do something about their pensions; you have to say “pensions have to grow more slowly than, let’s say, the average wage”. Otherwise, you get fiscal instability.

The interview was held on the 20th of October, 2023.