(Thawt Hawthje, CC BY)

They are effectively pushing this investment despite the fact that Europe and Russia are at odds with each other. Questions concerning the economic rationale behind this investment are raised in Russia as well.

(Infographics Bogusław Rzepczak/ CC by Thawt Hawthje)

On September 4th, 2015, the Russian Gazprom and the German companies BASF and E.ON, the Dutch-British Royal Dutch Shell, the Austrian OMV and the French ENGIE signed an agreement on the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline. The main shareholder is Gazprom (51 per cent), while the share of the remaining companies is 10 per cent except for the French company, whose share is 9 per cent. The capacity of the third and fourth line of the Baltic gas pipeline will reach 27.5 billion m3 each, like in the case of the two already existing lines. This should increase the total capacity of the pipeline to 110 billion m3.

Russian, but also many Western sources, have commented on this event as a significant success for Gazprom and an example of the gas company’s effectiveness in very difficult conditions. It was also presented as a telling example of the ineffectiveness of the sanctions, which are not able to stop the largest European companies from doing business with the partner from the East. Some also wanted to see this as a manifestation of Russia’s strength and determination in achieving long-term objectives, and primarily as another example of the strong pressure exerted on Ukraine, which, according to Gazprom’s announcements, is to be completely deprived of income from the transport of Russian gas to the European market after 2019 when the transit agreement expires.

Why does Russia need a new gas pipeline?

Many negative assessments have also emerged. Particularly severe criticism has been directed towards the economic rationale of the project. The critics are pointing out the unfavorable downward trends in the demand for the Russian gas on the European market and the indirectly related problems with the utilization of the existing transmission capacity of the Nord Stream’s 1st and 2nd lines (put into operation on November 2011 and October 2012, respectively).

In the first two years of operation they were not even used at half capacity, as the gas transport through this route during that period reached only 11.8 billion m3 in 2012 (about 35 per cent of trans-mission capacity) and 23.6 billion m3 in 2013 (44.2 per cent of transmission capacity). In 2014 the gas transport increased to 36.5 billion m3, which meant that the Baltic gas pipeline’s transmission capacity was used at 66.4 per cent of capacity. The capacity utilization rate was similar in 2015.

Opinions that the project is detached from economic realities and is de facto unnecessary has been already raised during the construction of the Nord Stream’s first phase. Some pointed out that the existing capacity for the transmission of Russian gas to Europe already significantly exceeds the needs in this regard. They totaled 204 billion m3, including 143 billion m3 through the territory of Ukraine and 33 billion m3 through Poland.

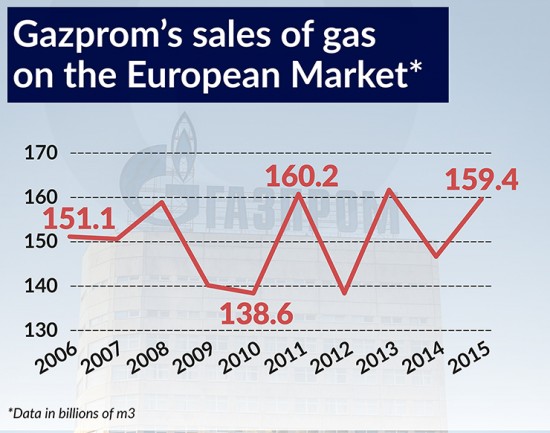

After the construction of the Nord Stream 1, these capacities increased by a further 55 billion m3, and reached almost 260 billion m3. For comparison, the largest historical volume of Gazprom’s gas sales on the European market (European Union plus Switzerland and Turkey) reached 161.5 billion m3 in 2013.

(Infographics Bogusław Rzepczak)

It is estimated that Gazprom’s sales on the European market reached 159.4 billion m3 in 2015 and that the average price of the supplied gas decreased by 35 per cent, from USD341/1,000 m3 in 2014 to USD222 in 2015. The analysts also point out that approx. 10-15 per cent of Gazprom’s sales comes from non-Russian sources of supply, which means that in recent years the actual size of the supply of gas from Russia to Europe stayed within the range of 120-140 billion m3.

There is a lot of misinformation mindlessly repeated by many analytical centers, in the analysis of the costs and supposed benefits that Russia/Gazprom is achieving as a result of the reduction or avoidance of the transit fees, due to reduced transmissions or the bypassing of Ukraine, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, and even Poland. The numbers don’t lie, however. The transport of a comparable volume of gas along the bottom of the Baltic Sea is significantly more expensive than using the traditional overland route.

We could refer to the analysis prepared by a well-known Russian gas market analyst Mikhail Korchemkin. He prepared calculations in two variants, i.e. for the year 2012 and 2020. The year 2012 covers 11.8 billion m3, that is the actual volume of gas transmitted to Germany through the Nord Stream gas pipeline. Sending that amount of gas from Russia via Ukraine, Slovakia and the Czech Republic to the reception point in Waidhaus in Germany (Bavaria) would cost EUR436m. The costs for the transport of the same amount of gas to the same point through the Nord Stream, and then through the Opal gas pipeline (Germany) and the Gazelle pipeline (Czech Republic) would be EUR1,751m. For the year 2020, with the assumed transport volume of 27.5 billion m3 of gas, these costs would be EUR1,052m for the land route and EUR2,188mfor the sea route.

In addition to the costs directly associated with the gas transport, analysts also point out two important factors working in favor of the existing route of its supply to Europe. In the case of the land route, the cost of purchasing the technological gas for the compressor stations needs is borne by Ukraine. For example, for the purposes of transit of the above mentioned volume of 11.8 billion m3, in 2012 Ukraine would have to purchase an amount of gas worth EUR132m from Gazprom. The transmission of the gas through the Nord Stream has therefore further diminished Gazprom’s revenues by that amount. In the case of the sea route, the cost of supplying gas to the Portovaya compressor station near Vyborg is borne by Gazprom (in 2012 the cost was EUR18m). The total negative effect for the Russian supplier in that regard alone is therefore EUR150m.

Deliveries executed through the Baltic gas pipeline instead of the transit route through Ukraine are also generating additional costs associated with the allocation of the existing transport routes for the exported gas within Russian territory, including the necessity of expanding the Ukhta-Gryazovets and Gryazovets-Vyborg gas pipelines.

An additional barrier for the Nord Stream are the formal limitations in the reception of Russian gas on the territory of Germany by the OPAL pipeline, with a capacity of 36 billion m3 (Greifswald-Brandov along the Polish-German border to the Czech Republic), and the NEL pipeline with a capacity of 20 billion m3 (the western line Greifswald-Rehden in the Netherlands, where Europe’s largest natural gas storage facility is located, with a capacity of 3.6 billion m3). The decisions of the European Commission did not exempt either of these pipelines from the EU regulations, which means that their owners are obliged to reserve half of the transmission capacity for access by third parties.

It is therefore reasonable to ask about the technical, formal and legal side of the reception of gas on the territory of Germany, if the Nord Stream’s transmission capacity is increased to 110 billion m3.

Gazprom has announced that with the expiry of the transit agreement with Ukraine from 2019 onwards it will not use the routes for the transport of gas through its territory. However, even if the construction of the Nord Stream 2 was completed within this deadline, we would still have to take into account that the agreements and contracts with the majority of the importing countries go far beyond the year 2019 and provide for specific reception points, associated with the supply route passing through Ukraine. Their renegotiation would create additional costs.

This applies in particular to countries such as Slovakia, Hungary, the Balkan countries, but also Austria, Italy and Germany. This also applies to the transit agreements with Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Due to the „ship-or-pay” formula applicable in such cases and the transmission capacities reserved by Gazprom, even in the absence of transit, in 2020 it would still have to pay EUR 315 million to Slovakia and EUR 55 million to the Czech Republic.

How will Europe react?

The construction of the Nord Stream 2 violates the basic priorities underlying Europe’s interests and the emerging foundations of the energy union. In spite of what the authors of the project may claim, the new pipeline, which hits the idea of European solidarity, is not the road to the diversification of the supply and the associated enhancement of the energy security of the EU countries.

In recent years, Russia has tried in many ways to take control of the Ukrainian and Belarusian gas pipelines, including especially the transit networks. These attempts have been successful with regard to Belarus. Gazprom ultimately acquired the Belarusian gas network from Beltransgaz in 2011 in two stages, paying USD2.5bn each time.

The struggle for the control of the gas pipelines was manifested in recent years by the famed gas „wars” with Ukraine and Belarus. Although outside Russia presented its actions as an expression of concern for the enhanced security of gas supplies to its customers in the EU, in practice these measures were based entirely on internal political and economic conditions, resulting from Russia’s policy towards those countries. As practice has shown, Russia did not start the „wars” in order to eliminate threats to the stability of supply, but conversely, such threats emerged each time as a result of the „wars” and the reduction of supplies on the part of Russia. By starting gas „wars”, Russia tried to force the gas recipients to exert pressure on the transit countries. The Nord Stream 2 is a new edition of this process.

The European Union’s Third Energy Package came into force on March 2011. The third package provides a basis for the formation of a competitive energy market in the European Union. Liberalization of this market, among others, forces competition in the energy market, strengthens the independence of the regulators, and introduces the necessity for the separation of production and distribution activities from trade and transport activities. One of the fundamental principles organizing the gas market, especially in the context of supplies imported to the European market, is the principle of third party access (TPA) to the gas transmission infrastructure.

Russia has been very critical towards the provisions of the Third Energy Package from the beginning. It was particularly concerned about the principle of TPA. Russia demanded that its gas transport projects be exempted from the principles of the Third Package, by being granted the status of a trans-European infrastructure project (the Trans-European Network – TEN). In the absence of such a status, the owner may utilize no more than half of the transmission capacity. Russia managed to obtain that status for the underwater part of the Nord Stream; however, the European Commission refused to grant such a status to its overland branches – NEL and Opal.

Poland is defending itself using wrong arguments

Poland has been actively opposing the idea of the construction of a new gas pipeline through the Baltic Sea. It is even seen as the leader of those countries of Central and Eastern Europe which have also expressed their opposition. However, some of the arguments used in these debates are irrelevant and thus easily refuted by the supporters of the Nord Stream 2.

The basic undeniable argument is that the new pipeline does not increase energy security and diversification of sources of supply, and thus stands in contradiction to the fundamental principles of the EU’s energy union. It may also cause problems in the operation of the LNG terminal in Świnoujście.

In a recent speech in the Polish parliament concerning Polish foreign policy in 2016, the Polish Foreign Minister stated: „We are critical towards the Nord Stream 2 project, which is an economically inefficient idea, aimed at increasing the European Union’s dependency on supplies from the same direction.”

While we could agree with the first part of this assessment, as well as with the assertion that „in fact, the Nord Stream 2 is not a business project, but a political project”, the idea that the project would „increase dependency” is highly doubtful. The Nord Stream is meant as a new route for the supply of the same Russian gas, which has thus far been supplied through the territory of Ukraine. The Nord Stream 2 in itself will not create any additional demand for Gazprom’s gas in the EU, nor will it generate any increased supplies as a result, and only that could strengthen its position in the European gas market. So with other conditions unchanged, the increase in transmission capacity alone, and in reality the replacement of the Ukrainian transit with transport through the bottom of the Baltic Sea, will in no way translate into the EU’s increased dependency on supplies from Russia.

Wojciech Jakóbik is even less convincing in his argument that for Poland the Nord Stream 2 pipeline is an obstacle to the diversification of energy sources, presented in an article published in the CE Financial Observer. The author is basing his entire argument on the unfounded and essentially erroneous idea that the Nord Stream 2 equals cheap gas from Russia. And since the new line equals – according to the author – „cheap supplies from Russia”, Europe is threatened by „the saturation of the European market with gas from Gazprom” and „the possible flooding of the German market with gas from Russia”. „Cheap gas from Russia will (also) block Poland’s open access to gas trade in other European countries.”

We do not know the basis for the author’s perception that the Nord Stream 2 is an important factor in the improvement of Gazprom’s competitive position on the EU market by enabling the supply of cheap gas. The question therefore arises as to why the Russian monopoly is not utilizing this possibility in the supplies currently delivered through Ukraine, Poland or through the Nord Stream 1?

The gas sent through the Nord Stream 2 will come from the same Yamal gas fields. The supply route will not be any shorter, and the cost of transport, even in the light of the cited studies, will be significantly higher than for the existing overland route. It cannot therefore be seen as a source of cheap gas supplies. The reserves for Gazprom’s price reductions have long been known and requested by the recipients. This entails a departure from the formula for setting gas prices in multi-annual contracts in connection with the prices of liquid fuels and a broader inclusion of the gas spot market prices. But such an approach is in no way related to the routes of the Russian gas supplies to the European market.

In the discussions about the unnecessary construction of the Nord Stream 2, the idea also appears that it could pose a threat to gas supplies using the Yamal pipeline through Poland. From the point of view of Gazprom’s intentions and policies, the supply of gas through the pipeline Yamal-Europe should not be at risk. The pipeline on the territory of Belarus was owned by Gazprom from the beginning, and on the territory of Poland it was co-owned by Gazprom. Considering that in the years 2010-2011 Gazprom took over the entire system of gas transmission pipelines on the territory of Belarus, and that the rates for transit through Poland negotiated in 2010 are three times lower than the European average, or the Ukrainian rates, it seems unlikely for Gazprom to allocate the gas supplies to the Nord Stream pipeline instead of the Yamal pipeline.

A great game, but what is the stake?

In its November report (World Energy Outlook 2015), the International Energy Agency indicated that in the current conditions Russia cannot afford the simultaneous construction of several very expensive pipelines. The decrease in the prices of Russian gas has significantly limited its ability to finance projects with own resources and the sanctions are making it harder to access international sources of financing. According to many Russian analysts, the simultaneous construction of the Power of Siberia pipeline from Yakutia to China, the Nord Stream 2 and the Turkish Stream, is a straight path to Gazprom’s bankruptcy. It is estimated that the Russian monopoly has already invested USD 17 billion in the implementation of the southern corridor for gas sup-plies to Europe, i.e. the already cancelled South Stream gas pipeline, and the increasingly doubtful Turkish Pipeline.

Is Russia determined to implement the Nord Stream 2 in spite of such clearly unfavorable facts and figures, and the negative experience with the effective European boycott of the South Stream gas pipeline? Analysts agree – there is no such need or possibility. Failing to see any, including economic, rationale for this project, they are raising the question – does Russia really have to unreasonably lose USD20-30bn in order to deprive Ukraine of USD2bn of income from gas transit (winding down transit through Ukraine is currently the only justification for the project).

In general, however, it seems impossible to reconcile the EU’s strong political and economic support provided to Ukraine in its transformation, an important element of which is opposing Russia, with the simultaneous (albeit passive) support for the Nord Stream, which would supposedly guarantee greater security of supplies than transit through Ukraine.

The crucial question concerns the importance of the fundamental principles of European policy, which undoubtedly include solidarity. Must it give way to the business interests of large companies from the biggest European countries in an area of the economy as important as energy, but at the same time remain binding in the field associated with the influx of refugees?