These are the latest assessments of the European Banking Authority (EBA). Last spring, the General Board of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) assessed that the repricing of risk premia is one of the main threats to the stability of the European financial sector. Markets were optimistic, stock prices rose, spreads on debt securities tightened, and the prices of real estate in the United States and some other countries, as well as in big European cities, soared above the pre-crisis peak levels. All this happened amid very low volatility. It looked as if investors lost their risk awareness.

At the same time, the rate of growth of the European economy was weak and still below potential, which was accompanied by political and geopolitical risks. All of this meant that a repricing of risk premia could occur at any time. One year after this warning was issued, we’re living in a world where volatility has returned to markets. Meanwhile, despite the strengthening of economic growth, the stability of the macroeconomic conditions is not at all certain. This is aggravated by political and geopolitical uncertainty, which is not decreasing.

On the other hand, there is a growing risk of protectionism, which could significantly affect volatility and liquidity in markets. Despite the return of volatility, a sudden repricing of risk premia could still take place, leading to even greater drops in asset prices, especially the riskier ones. According to the EBA’s report from April, this risk for the European banking sector has increased.

Banks in the European Union are somewhat stronger

Every quarter, the EBA publishes the “Risk Dashboard” for the European banking sector, in which it summarizes the main risk factors and the banks’ weaknesses. It analyses changes in the risk indicators. The selected sample of 190 banks is representative for the entire European Union. Three Polish banks participate in the study–PKO BP, Pekao and BZ WBK.

The latest update shows that at the turn of 2017 and 2018 the assessment of market risk changed from medium to high. The “risk level” is a synthetic assessment of the probability of materialization of the risk factors, and their likely impact on the banks. The assessment takes into consideration the evolution of market and prudential indicators, the assessments of the national supervisory authorities, the banks’ own assessments, as well as the views of the analysts.

Let’s start with the positive conclusions. The European Union’s banking sector keeps strengthening. In the last quarter of 2017–the most recent period for which full data are available–the banks once again strengthened their capital ratios. The CET1 core capital ratio increased by 20 basis points, from 14.6 per cent in the third quarter of 2017 to 14.8 per cent at the end of the year. It is–following a temporary decline–once again at the highest levels recorded since the end of 2014.

Moreover, all the institutions examined by the EBA recorded CET1 core capital ratios above 11 per cent, which means that even the banks that are doing relatively poorly have made significant progress. We should also add that the Tier 1 capital ratio increased to 16.2 per cent on average, and the total capital ratio grew to 19 per cent.

The problem–which is acute amid renewed growth and growing credit needs of the economy–is that the increase in the capital ratios resulted from a decrease in the total amount of risk exposures (mostly in respect of credit risk). This means that many institutions have not yet finished the post-crisis process of deleveraging and are not ready to launch new lending activities.

The phenomenon of deleveraging–at the aggregate level for the European Union–will take a lot more time, because it results not only from the inability to raise capital or from weak profits. In many countries it also results from the need to clean up non-performing loans from the portfolios. The process of offloading of the pile of bad debts has begun. The average ratio of non-performing loans (NPLs) to the total value of loans continued to decline in the Q4’17, and amounted to 4.0 per cent, reaching the lowest level since the Q4’14.

Although we cannot really say that the European mountain of bad debts is melting as fast as the glaciers in the Alps, it is worth noting that in three years it has decreased by a third, from over EUR1.12 trillion to EUR813bn. Bad debts were offloaded by large institutions, but especially by small banks. The diversification of the banking sectors in the EU member states is still very high in this respect. For example, NPLs represent from as little as 0.7 per cent of the banks’ loan portfolio in Luxembourg to as much as 44.9 per cent in Greece. In Italy, where the banks hold in their portfolios about a quarter of all NPLs in the EU, the volume of bad debts fell from almost EUR250bn in the Q1’17 to EUR186.7bn at the end of last year. The ratio of NPLs fell from 14.8 per cent to 11.1 per cent.

The advances in the process of disposal of bad loans from the portfolios are clearly visible in Cyprus, while the progress is still slow in Greece, where the volume of NPLs still exceeds EUR100bn. The volume of NPLs is also significant in France, where it amounts to EUR135.5bn, and in Spain (EUR106.2bn). The volume of NPLs in the portfolios of Polish banks is just EUR6.bn (according to the EBA methodology) and seems relatively small compared to the aforementioned markets. However, the ratio of non-performing loans in the Polish banking sector is 5.8 per cent, which is significantly above the EU average and it is worth noting that this result was recorded amid an economic boom.

The greatest weaknesses

The EBA is far from concluding that the problem of bad debts now only affects the banking sectors of a few select countries. According to the EBA, “the still high amount of NPLs in banks’ balance sheets remains a vulnerability for the European banking sector as a whole”.

The progressive strengthening of the capital ratios, the gradual decline in bad debts, the inflow of deposits, and the improvement of the liquidity ratio–these are all positive trends in the banking sector in the European Union. However, even these positive trends are accompanied by negative phenomena. For example, the decrease in the volume of non-performing loans was accompanied by a simultaneous reduction of the coverage ratio by 20 basis points, to 44.5 per cent.

The European banking sector is doing very poorly in terms of profitability, which continues to fluctuate, even though it has improved from the lowest level recorded in the Q4’16, when the average ROE for the sample of examined banks reached 3.3 per cent. The return on equity ratio differs significantly between the individual countries and ranges from minus 16.5 per cent in Cyprus to 17.4 per cent in Hungary.

In the EU as a whole, at the end of last year the average ROE decreased to 6.1 per cent from 7.2 per cent in the Q3, but was still 2.8 percentage points higher than one year before that. The EBA indicates that at the end of the year the ROE always exhibits a seasonal decrease in comparison with the previous quarter. According to the EBA, 53.1 per cent of European banks have a ROE ratio below 6 per cent, and almost ¾ of them (73.2 per cent) have a cost to income ratio (C/I) above 60 per cent. The average C/I ratio in the European Union is 63.4 per cent. No improvement was recorded here.

Moreover, the banks owe last year’s increase in profitability to the surge in the net trading income, which reached 8.5 per cent y/y. And this is the most unstable part of their business.

The EBA indicates that “profitability remains a key challenge for the EU banking sector (…) and the return on equity remains below the cost of equity, with legacy assets, cost-efficiency and banks’ business models still being some of the main obstacles towards reaching sustainable profitability levels”.

Where the risk is high

Credit risk has occupied the top spot on the “Risk Dashboard” for many years. Despite the decreasing overhang of bad debts, the EBA did not lower the assessment of this risk. It pointed out, however, that the trend is stable.

The EBA believes that although there is visible progress in the reduction of the NPL volume and the increase in activity on the NPL secondary market, the previously applied methods are not enough to tackle the problem. That is why it supports last year’s idea of the European Commission, which proposed, as part of the CRD IV and CRR amendment plans, among other things, the introduction of an obligation for banks to create write-downs for non-performing loans from own funds. The low levels of write-downs for NPLs and the low market prices of such debt are currently discouraging banks from solving the problem.

Operational risk still remains high, and is primarily associated with cyber-crime and data security. The EBA notes that as far as IT and communications technologies are concerned, banks are increasingly relying on outsourcing, which may generate additional problems. In the case of operational risk, the trend is stable.

The risk associated with government debt in banks’ portfolios remains high as well. There is still a danger of a return to the “vicious circle”, i.e. the mutual negative impact of the public debt valuation on the banking sector and vice versa. We witnessed such a situation when the debt crisis of 2010-2012 broke out. The EBA emphasizes that an increase in interest rates in some countries could negatively affect the debt servicing costs. This also includes sovereign debt.

The risk associated with banks’ low profitability remains high, but shows a downward trend. This is due to the fact that the economic recovery is broad-based and should support banks’ profitability. On the other hand, continued global economic uncertainty poses a risk. The conclusion, however, is that banks have failed to develop models for achieving repeatable profits based on lasting and sustainable foundations.

Over the last two years, there has been a decrease in fines imposed on the banking sector by the regulatory bodies for cases of flagrant misconduct. However, court cases are still pending, and the rulings in civil litigation may affect consumer confidence and the profitability of banks involved in the disputes. Reputation risk has fallen, however, and is now assessed to be at a medium level.

There are no safe havens anymore

The optimism of markets, the rising asset valuations and the tightening of spreads all faltered at the end of 2017, following the adoption of tax changes in the United States. Let us recall that they are supposed to lead to an acceleration of GDP growth in the perspective of the next decade, but will increase the federal deficit by about USD1 trillion. Immediately after the adoption of the law, the yields on the US treasury bonds increased significantly for the first time in many months. Their prices are still falling. On April 25th, the yield on 10-year Treasury notes exceeded 3 per cent for the first time in over four years.

The upward trend on the US stock market broke down at the end of January, and the correction has lasted more than three months. Throughout this period, the VIX index, which is seen as a measure of the market expectations of volatility, did not fall below 15 points, while before the correction its value rarely exceeded 10 points.

Moreover, at the turn of January and February markets sent out one additional alarming signal. The decline in prices on the stock market was accompanied by a sell-off in almost all other classes of assets. For the first time since the crisis, it covered both shares and bonds.

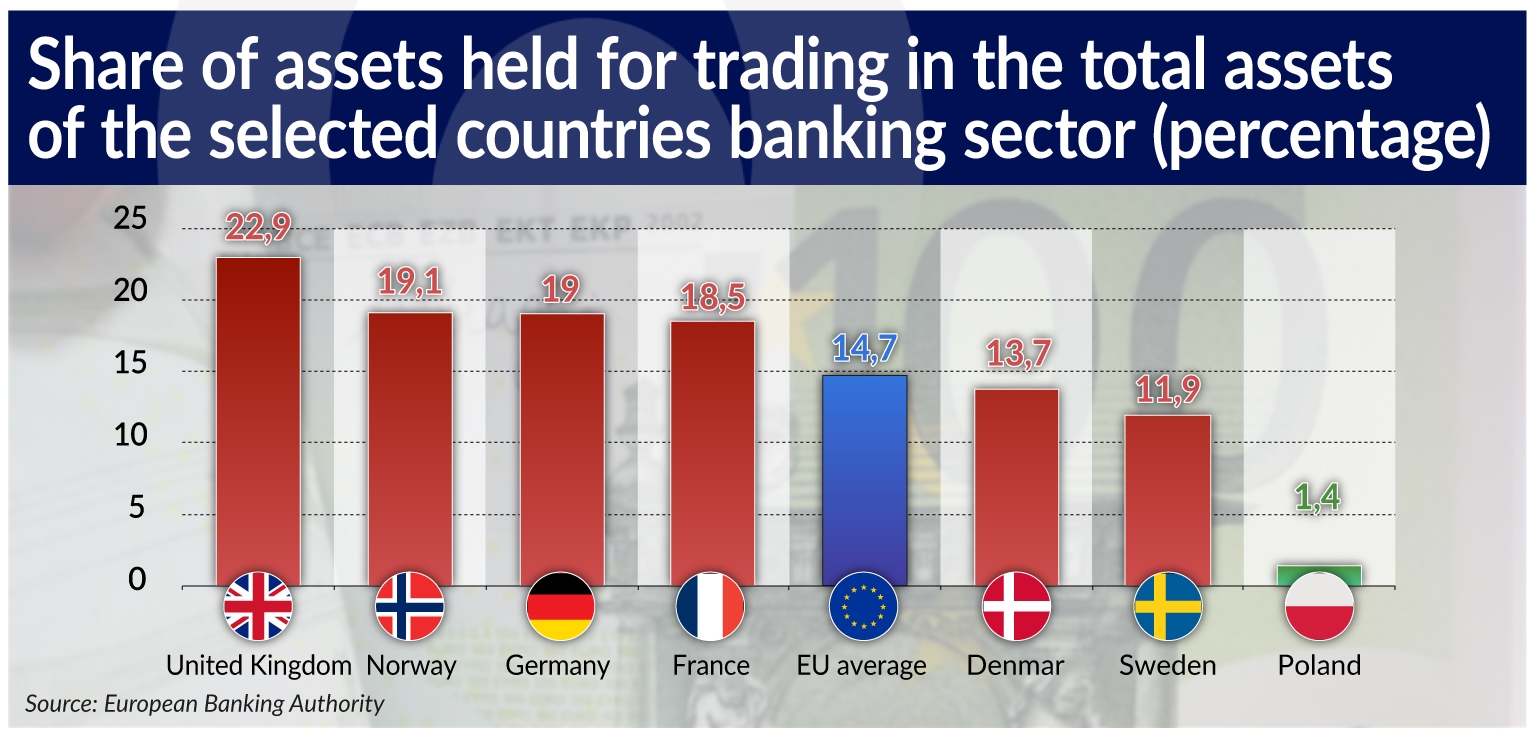

The return of volatility constitutes a big threat, especially since banks improved their results in 2017 mainly due to their net trading incomes. The structure of assets in certain countries means that local banks are much more vulnerable to the market situation there. While the assets held for trading account for 14.7 per cent of banks’ total assets on the EU on average, there are certain countries where this share is significantly higher. These, of course, include the United Kingdom (22.9 per cent), but also Germany (19 per cent) and France (18.5 per cent). The return of volatility means an increased risk of a possible repricing of assets held for trading, particularly in the banking sectors of these countries. And these are the largest banking sectors in Europe.

Capital market instruments account for 2.4 per cent of bank assets in the EU on average, while debt instruments account for 12.8 per cent on average. But there are many countries where their share is much higher, and this is presumed to mainly represent the public debt of their own governments. The highest share was recorded in Hungary–27.1 per cent, followed by Romania, Slovenia and Malta (26.9 per cent, 25.9 per cent and 25.6 per cent, respectively). In Poland this share is also significant and amounts to 21.8 per cent. As for derivative instruments, their share in the total assets of banks is the highest in the United Kingdom (13.5 per cent) and in Germany (12.8 per cent).

In the structure of liabilities, deposits from other banks are the instrument that is exposed to the highest risk of liquidity-related turbulences amid market stress. Across the European Union, they only account for 6.4 per cent of liabilities. However, in Luxembourg they account for 19 per cent of total liabilities, in Lithuania for 16.5 per cent, and in Estonia for 15.2 per cent of total liabilities. A high share of financing from the interbank market in liabilities is also recorded in the case of banks in Germany (13.5 per cent) and in the Czech Republic (13.2 per cent).

Another area of growing risk–at least in some countries–is the real estate market. The ESRB already drew attention to this issue a year ago. In the case of Swedish banks, the exposures to real estate companies account for 60.3 per cent of all exposures to non-financial enterprises. These exposures reach 49.7 per cent for Danish banks and 45.4 per cent for banks in Finland.

Considering the credit and market risk together with its possible effects on profitability, as well as the structure of bank assets and liabilities in the individual EU countries along with the exposures to government debt, it is difficult to find a banking sector that can be considered immune to destabilization.