Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

The path to the stabilization of the value of money—which was one of the greatest achievements after Poland regained its independence in 1918—was not at all simple or obvious. For many decades the Polish economy was divided by the partition lines, and its potential was heavily damaged not only during the First World War, but also during the struggle for Poland’s borders, which lasted several years, especially in the eastern parts of the country. When Poland regained independence, there were at least five rapidly devaluing currencies in circulation—Polish marks, German marks, old Tsarist rubles, post-revolutionary Soviet rubles and Austrian crowns.

However, the foundations of the future bank of issue already existed in the form of the Polish Loan Bank (Polska Krajowa Kasa Pożyczkowa), which was founded during the First World War and which was issuing Polish marks. It became the first—as we would call it today—central bank of the newly reborn Polish Republic, while the Polish mark became the first Polish currency. These designations may be somewhat exaggerated, considering the fact that the main role of the Polish Loan Bank was to print vast amounts of money—which did not correspond to economic output—in order to meet the growing needs of the Ministry of State Treasury.

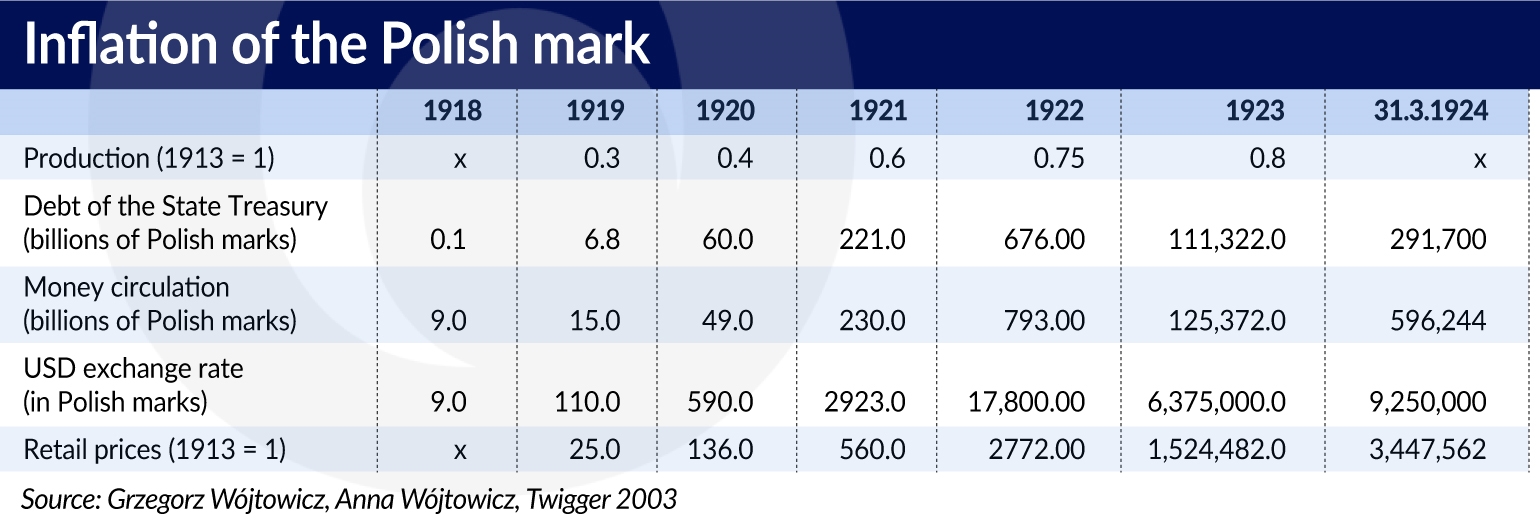

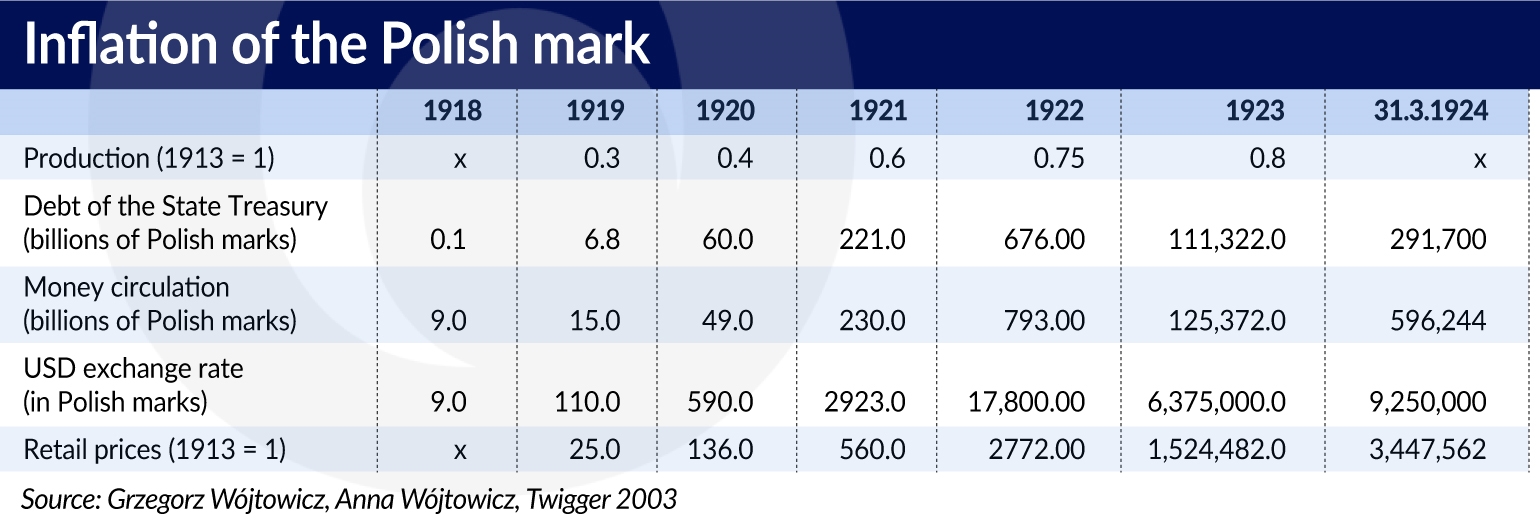

The financial needs of the Polish state associated with the continued armed struggles, as well as the reconstruction and consolidation of the country, were much greater than the need for currency stabilization. This resulted in spiraling inflation. The rate of the financial deterioration is well illustrated by the data collected in the book “A Monetary History of Poland” by Grzegorz Wójtowicz, the former Poland’s central bank NBP Governor, and Anna Wójtowicz.

In six years, from 1918 to March 1924, the debt of the Polish State Treasury increased from Polish marks 0.1bn to 291,700bn. The pace of work conducted by the Polish Loan Bank is illustrated by the fact that money circulation, including the currencies of the former partitioning powers, increased from Polish marks 9bn to 596,244bn. Retail prices increased by nearly 3.5 million times compared with levels recorded before the First World War. In this situation, the only way to protect currency value was to hold on to gold and foreign currencies, or at least some of them, as, for example, the German mark was losing value just as quickly. The scale of collapse of the Polish mark was clearly visible in its exchange rate in relation to the USD. The USD exchange rate increased from Polish marks 9 in 1918 to 9.25m in March 1924.

Władysław Grabski, an economist and a politician, who sat in the Russian State Duma before the First World War, was undoubtedly among those who were the most aware of the importance of bringing order to the State Treasury and stabilizing the value of money as a necessary foundation for the independent Polish state. During his time in the Russian parliament, he conducted calculations which proved that it was not the Russian Empire that was carrying the financial burden of maintaining the annexed Polish territories, but it was in fact the Congress Kingdom of Poland that was being exploited by Russia. Grabski was sent to the Tsarist prison for his views, but his calculations proved useful during the settlements with Soviet Russia after the peace treaty was concluded in Riga in 1921.

Grabski prepared the first plan for the stabilization of state finances in the spring of 1920, when he became the Minister of Treasury for the first time since the end of the war (he previously served as the Minister of Treasury during the rule of the Regency Council). The plan provided for a reduction of budget expenditures and a suspension of the issue of Polish marks for budgetary purposes. Their value was supposed to be backed by a compulsory internal loan and by loans from Poles in the United States. The escalation of the Polish-Bolshevik relations hindered the chance for the stabilization of the State Treasury. The new war effort was financed by an “inflation tax”, which is always the most powerful of the taxes that can be employed by a government in need of financing.

In the summer of 1921, after the end of the war with the Soviet Union, Grabski, who was no longer a member of the government, presented a draft law on the improvement of the State Treasury, which had become even more destabilized in the meantime. In addition to putting an end to the previous policy of printing excessive amounts of money that didn’t correspond to the country’s actual economic output, and reducing the budget expenditures, which included among others a reduction in clerical staff, the plan also provided for tax increases and an internal loan based on the value of the dollar. However, the successive governments lacked the political will to pursue the necessary budget cuts.

The idea of stabilization of the State Treasury returned to the political agenda at the beginning of 1923, following a series of price increases. This objective was adopted by the President of the Republic of Poland, Stanisław Wojciechowski. There was still no political will for the implementation of Grabski’s radical plan, although Grabski himself was again appointed as the Minister of Treasury in the government of Władysław Sikorski and then remained in this position in the next government of Wincenty Witos. Grabski then commissioned Professor Roman Rybarski from the Jagiellonian University, to prepare the statute for the future Bank Polski (Bank of Poland), which was established a year later.

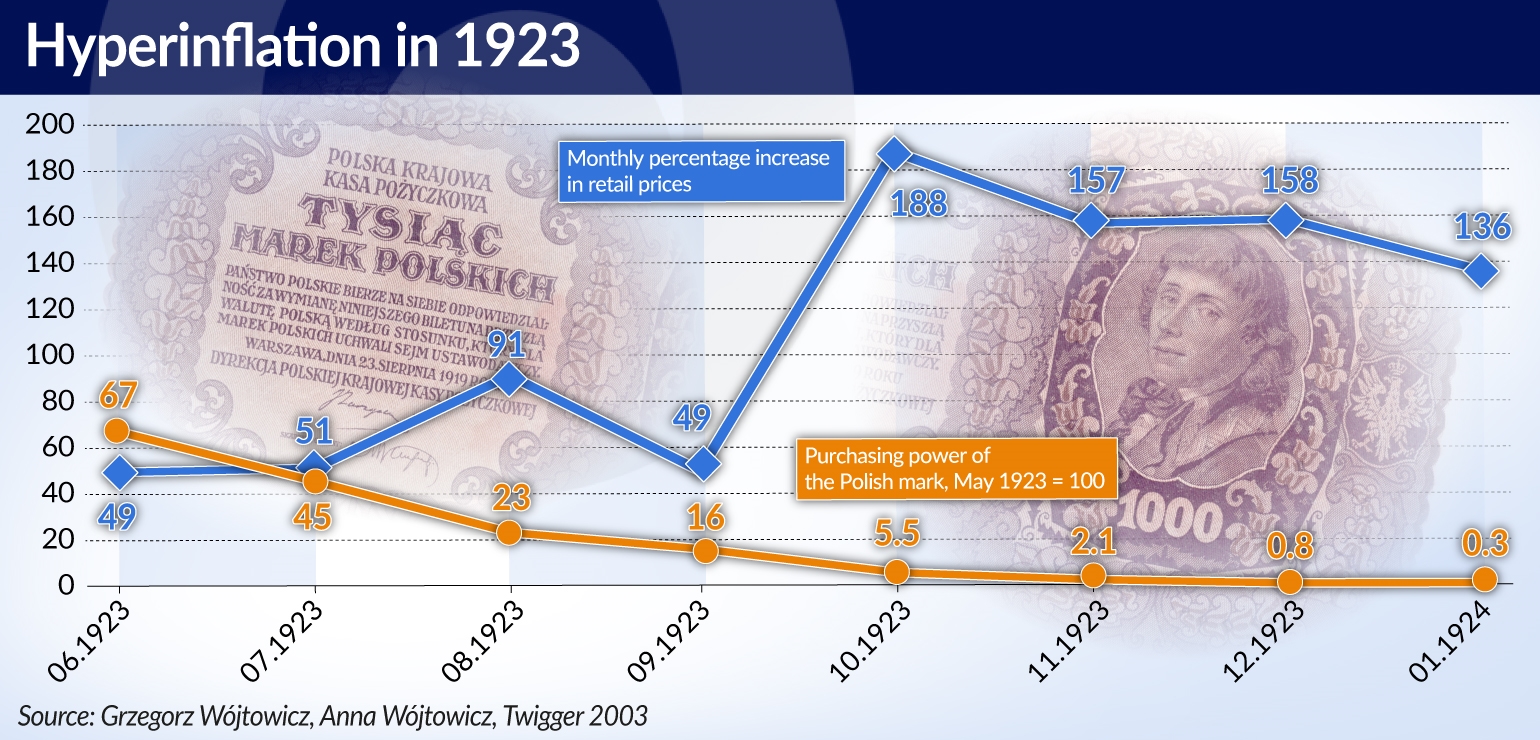

Meanwhile, inflation started rising rapidly. According to Jerzy Tomaszewski’s book “The stabilization of the currency in Poland 1924-1925”, the rate of price growth increased from 12.9 per cent per month in May, to 48.5 per cent in June, and 51 per cent per month in July 1923. Fearing hyperinflation, the Polish Sejm (lower house of the Parliament) passed the introduction of a property tax, but Grabski resigned in protest against the government’s failure to pursue decisive action.

During that time, the dominant view among economists was that the State Treasury could not be rescued without financial assistance from abroad. Such were the experiences of the fight against hyperinflation in Austria. Germany was also fighting hyperinflation at that time, but the German idea of basing the value of the new marks (so-called Rentenmarks) on the mortgages of landed estates, industrial and commercial enterprises and banks was only just being implemented, and it was difficult to determine whether it would prove effective. Moreover, the effort to stop hyperinflation in Germany was also aided by loans from the United States, while Austria agreed for the country’s finances to be managed by an external commissioner.

In the autumn of 1923, Poland was involved in difficult negotiations concerning foreign loans. It was much easier for Austria and Germany to obtain financial support from abroad than for Poland. Hyperinflation was scaring away potential lenders. The price of the assistance also included the risk—as in the case of Austria—that the country could lose its financial independence. The mission of the British Deputy Minister of the Treasury, Hilton Young, who participated in the work on the 1924 budget, advised that Poland should, among other things, invite British officials who would control the implementation of the budget.

President Wojciechowski decided to appoint a non-partisan government with Prime Minister Władysław Grabski, who invariably believed that Poland could improve the condition of its Treasury on its own. Grabski did not have much confidence in foreign lenders, and especially the British. Their advice involved deep cuts in military expenses, which was unacceptable for political reasons, as well as shifting the costs of education from the central government to the local governments, which was also unrealistic. Grabski feared—as he wrote in his memoirs “Two years of work at the foundations of our statehood,1924-1925”—that the goal of Young’s mission was above all to find employment for the British tax officials who had just lost their jobs in Egypt, which was being abandoned by the United Kingdom. The British advisors were ultimately dismissed.

In January 1924, Grabski’s government received full authorization to implement the fiscal reform, but even then the MPs were not ready to fully support him. The Sejm only provided authorization for half a year. As it later turned out, this accelerated the implementation of the reform, and its main objectives were completed in four months.

Grabski’s plan was to stop the financing of government expenditure by the Polish Loan Bank, to introduce the property tax already passed in the summer of the previous year (covering assets in excess of 10,000 gold francs of that time), and to raise the transport tariffs of the Polish State Railways in order to ensure their financial self-sufficiency. In the part concerning the currency, Grabski’s plan provided for the establishment of a new issuing institution—Bank Polski.

The breakthrough moment—as Feliks Młynarski, the Vice President of Bank Polski recalled in the book “10th Anniversary of the Reborn Poland 1918-1928”—came on February 1924, when the government closed the credit line at the issuing institution. This was made possible due to the vigorous collection of advance payments for the property tax. In a short period of time two additional advance payments were collected, without the possibility of early deduction before the end of the year.

As a result of the introduced changes, the exchange rate of the Polish mark stabilized at the level of Polish marks 9.35m for USD1. This rate was adopted as the starting point for the currency reform. A new currency was established—the Polish zloty—whose value was equal to 1 gold Swiss franc.

The Polish marks were converted into the Polish zloty at the stabilization rate of Polish marks 1.8m for one Polish zloty . After the reform, the exchange rate of the USD was the Polish zloty 5.18 for USD1.

The value of the Polish zloty was backed by the small but growing gold stocks, derived in part from the dissolution of the reserves of the Austro-Hungarian Bank, by Russia’s payments of compensations guaranteed by the Riga Treaty, and in part by a loan obtained from Italy and from the voluntary contributions of Polish society. Work on the establishment of a new issuing institution was quickly launched. In accordance with the statute prepared by Professor Rybarski, it was given the form of a joint-stock company.

At the same time, a subscription for the shares of Bank Polski was launched. Its value reached Polish zloty 100m. Initially there were some problems with the subscription. Landowners and wealthy peasants, who were paying property tax advances at that time, were not willing to participate in that process. Officials and military officers took part in the subscription more willingly. But, as Władysław Grabski later recalled, “this only happened when I decided to accept payments for the shares in Polish marks, and after I also ordered, as an incentive for these groups, to accept subscriptions for shares in instalments, whereby the unpaid part of the subscribed shares was to be paid in advance by the government to the account of Bank Polski.”

The reaction of Polish society, weary of years of inflation, was more enthusiastic. The subscription of shares ultimately ended up as a great success of Grabski’s government. Industrial owners purchased 38.2 per cent of shares of Bank Polski, commercial banks—as we would call them today—purchased 13.7 per cent, civil servants and military officers purchased 12.7 per cent, state officials purchased 8 per cent, and the remaining portion was purchased by cities, rural communes, cooperatives, municipal savings banks, and other business entities.

The government was able to reduce its interest in the share capital to 1 per cent. The circulation of new money was backed in 30 per cent by gold and foreign currencies, and in 70 per cent by promissory notes, silver, silver coins, State Treasury obligations and with the right to issue coins.

There were also some problems with the appointment of the management of Bank Polski. Stanisław Karpiński, a senator, and before that a minister of the Treasury, who supported Grabski during the fiscal reform, was appointed as the first governor. The appointment of the Council of Bank Polski was a moment of crisis. Grabski wanted the Council to be distinguished by high competences. As he recalled: “In my understanding, Bank Polski should be an institution serving the vital interests of the state. When I realized, that organized economic spheres wanted to turn the bank into a subordinated tool of influence, rivalry and ambitions of various groups and professions, I decided to fight them, well aware that it would cost me dearly. From that point on, I had the landowning classes against me.”

Grabski was able to win this battle, but in the following months some controversies emerged between him and Bank Polski. He wanted the bank to continue to intervene in order to maintain the exchange rate of the Polish zloty, but Karpiński objected. As a result, Prime Minister Grabski resigned in November 1925.

The operation of Bank Polski was inaugurated on April 28th, 1924. New banknotes of Bank Polski with face values of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 zlotys were introduced. Silver coins, or rather silver alloy coins, were struck in denominations of 1, 2 and 5 zlotys. Coins with denominations from 1 to 50 grosz were struck in bronze and nickel.

The fiscal and monetary reform was carried out successfully, but the process of monetary and budgetary stabilization took much longer.

In accordance with Grabski’s predictions, the quick suppression of inflation led to a post-inflationary recession in the economy. This scenario was feared by the entrepreneurs, who wanted to have more influence on the appointment of the managing personnel of Bank Polski. Production dropped by over a dozen per cent, which would probably be considered an unacceptable crisis according to today’s standards. In addition, the catastrophic weather conditions in 1924 resulted in a decline in agricultural harvests and the necessity of importing agricultural products. At the beginning of 1925, a customs war broke out between Germany and Poland. It resulted, among other things, in a sharp decline in coal exports, which were the main source of foreign currency in the Polish economy.

The recession was followed by a return to inflation. But this time it was not as hard as before Grabski’s reform. A more complete stabilization and economic recovery only came in 1926, just before the May Coup (a coup d’état carried out in Poland by Marshal Józef Piłsudski in May 1926). The new authorities did not change the tax and monetary policies introduced by Grabski. The state budget remained balanced and even achieved a financial surplus.

The process of stabilization of Polish money formally ended on October 13th, 1927, when President Ignacy Mościcki signed a regulation establishing the exchange rate of Polish zloty 8.91 for USD1.

With this article we inaugurate celebrations of the 100th anniversary of Poland’s independence.