Faced with a recession, European banks would incur comparable losses as in the previous edition of the test, but this time the assumed conditions were more stringent. The starting point for 2018 stress tests conducted by the European Banking Authority (EBA) were the banks’ balance sheets at the end of 2017. The banks were subjected to two scenarios: the baseline scenario and the adverse scenario. The macroeconomic and market assumptions for the baseline scenario were provided by the European Central Bank (ECB). Meanwhile, the adverse scenario, devised by the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), assumed a shock on the asset market — which would be stronger than in the exercise conducted three years ago — and the subsequent return of a deeper recession.

The shock assumed in the extreme scenario was to take place in 2018 and was supposed to reflect, among other things, markets’ response to a hard Brexit. Moreover, since the beginning of 2018 banks are required to comply with the International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9, which replaced the International Accounting Standard (IAS) 39. This additionally affects the banks’ capital ratios.

In total, the banks surveyed in 2018 exercise represent 70 per cent of total EU banking sector assets. In the adverse scenario, all of the surveyed banks were able to keep their CET1 capital ratios above the minimum requirement of 4.5 per cent. UK’s banks performed the worst among the group. The stress tests have shown that while there are still many weak and risky large banks in Europe, the sector as a whole is now stronger than before.

“The outcome of the stress test shows that banks’ efforts to build up their capital base in the recent years have contributed to strengthening their resilience and capacity to withstand the severe shocks and material capital impacts,” said Mario Quagliariello, the Director of Economic Analysis and Statistics at the EBA when commenting on the outcome of the exercise.

“The outcome confirms that participating banks are more resilient to macroeconomic shocks than three years ago. Thanks also to our supervision, banks have built up considerably more capital, while also reducing non-performing loans, and among other things, improving their internal controls and risk governance,” said Danièle Nouy, Chairman of the ECB’s Supervisory Board, as quoted in a press release of the European Central Bank’s Banking Supervision.

The tests are conducted at the highest consolidated level, and therefore the subsidiaries of bank groups do not directly participate. This is the case for most Polish banking institutions. Out of the Polish banks, only state-owned PKO BP participated in the stress tests. As Pekao, the second largest Polish bank, was recently “nationalized”, it also participated the survey. In the previous editions it was treated as a part of the UniCredit group.

Greek banks were also left out. Four largest banks from that country were “tested” separately according to the same methodology by the European Union’s supervisory system — the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). The results of these tests were announced in May 2018. Another bank absent from the test was Banca dei Monte Paschi di Siena, which was recapitalized by the Italian government two years ago, under the so-called precautionary recapitalization scheme. Previous stress tests have shown that under adverse conditions its capital would decrease by as much as 1,451 bps to reach -2.44 per cent in 2018.

In 2018 tests, the adverse scenario assumed a GDP decline 1 percentage point deeper than in the previous edition of the study. In this context, the scale of losses turned out to be comparable to the previous results, which means that the banks’ resilience has increased. Nevertheless, the capital of 25 per cent of banks would shrink by more than 525 bps. This shows that the European banking sector is recovering, albeit at a very slow pace.

What is the purpose of stress tests?

The point of the stress tests is to check the resilience of banks across the EU in a comparable way. Just as in the previous edition of the tests, there was no established capital threshold which would serve as a limit indicating whether the bank has passed the test or not. Such a criterion was used as a benchmark in the tests four years ago.

The methodology did not fundamentally change. Certain adjustments were introduced in the analysis of market risk, where a uniform method was applied for all portfolios measured at fair value.

During the tests, the banks apply the conditions included in the scenarios to their models and to the samples of various asset classes. The quality of these assets is tested, and it is checked where losses would occur, and how high they would be. Then, the results obtained from the samples are applied to the entire asset classes, after which the sums of hypothetical losses are calculated and their effects on the capital ratios are determined, i.e. how much capital a given bank must use to cover the incurred losses.

One novelty in 2018 tests related to the implementation of IFRS 9. The banks had already included the effects of the new standard in output data for the end of 2017. This restatement of data resulted in an average reduction in capital by 20 bps. Then, it was necessary to calculate the effects of IFRS 9 throughout the forecast horizon. They turned out to be lower than indicated in previous analysis prepared by the EBA. In the adverse scenario, in the forecast horizon the introduction of the new standard, and in particular the expected credit losses (ECL) model, would cause a shortfall in capital by a further 20 bps.

The EBA has presented two approaches to the effects of capital shortfalls. As the Basel III rules are introduced gradually, and some of them will fully take effect in 2022 or even after 2026, the capital ratios were calculated according to the currently applicable rules, i.e. in the ongoing transitional period (so-called transitional basis). At the same time, they were calculated as if the Basel III rules (i.e. the Capital Requirements Directive IV and the Capital Requirements Regulation within the European Union) were already fully implemented (so-called fully loaded basis). Overall, the differences are not significant, although they can be large for certain institutions. For the purposes of this article, the data are provided in accordance with the fully loaded basis, and data according to the transitional basis are optionally provided in parentheses.

The results derived from the banks are verified by a local supervision authority and the EBA coordinates these activities. Compliance with the methodology and the quality of results is ensured by a local supervision authority — the SSM for the Eurozone banks and the Polish Financial Supervision Authority (KNF) — for the two Polish banks. The supervision authority may verify the banks’ calculations, order them to be repeated, and may request the provision of additional data or samples.

Scenarios in 2018 tests covered the period from the Q1’18 to the end of 2020. As in previous exercises, the tests were conducted on the static balance sheet assumption. This means that over the entire surveyed period banks do not adjust their balance sheet structure to the changing external conditions. It remains the same as at the end of 2017.

Market shock and deep recession

The attention of all those observing the stress tests is obviously focused on the outcome of the adverse scenario. In both scenarios, the tests measure the impact of credit, operational and market risk on banks. The effects of the scenarios are to be reflected not only in changes in the capital ratios, but also in banks’ net interest income and the profit and loss account.

In previous tests in 2016, it was precisely the credit risk that had the strongest impact on banks’ capital shortfalls. Non-performing loans were responsible for losses of EUR349bn. In 2018 tests, credit risk losses were also the largest and amounted to EUR358bn.

The tests also examined the impact of operational risk, including conduct risk, on banks’ capital. Losses resulting from operational risk amounted to EUR82bn, while in the previous edition they were EUR105bn. Aggregate losses stemming from exposures to market risk, including counterparty credit risk, amounted to EUR94bn (three years ago, they amounted to EUR98bn). Let’s keep in mind that 51 institutions were tested three years ago. This means that the size of the losses is similar as in the previous edition.

What were the assumptions of the adverse scenario? The adverse scenario reflected four systemic risks identified by the ERSB as the most material threats to the stability of the European Union financial sector. The first of these is the most important — an abrupt and sizeable repricing of risk premia in global financial markets, triggered, for example, by a shock associated with Brexit. This means that asset prices in global financial markets decrease, and the yields on securities rise along the entire curve. The result is a sharp tightening of financial conditions.

The remaining threats are derived from the market shock. There is an adverse feedback loop between banks’ weak profitability and the weak growth of the economy. There are growing concerns regarding the sustainability of public and private debt. There is an increase in the liquidity risks in the non-bank financial sector, with spillovers throughout the entire financial system.

The scale of the market shock varies across countries and different asset classes, but is the most pronounced in countries with higher public debt stability risks — Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal. On average, the long-term interest rates in the EU would increase by 83 bps in 2018.

The shock would start on the stock markets. The adverse scenario assumed that the value of S&P500 would drop by 23.6 per cent by 2020, however, in 2018 the stock prices in the United States would fall by as much as 41 per cent. Stock markets in the European Union would decline by an average 30 per cent. Against this background, WIG, the broadest index of the Warsaw Stock Exchange would only drop by 24.1 per cent. It’s worth noting that 2018 American stress tests assumed that in the extremely adverse scenario equity prices would fall by 65 per cent in early 2019, compared with the end of 2017.

The market shock and the tightening of financing conditions would be followed by a deep global recession, although its scale would vary across countries. In the adverse scenario, the GDP in the EU would be 8.3 per cent lower in 2020 than under the baseline assumptions. The cumulative decline in GDP in 2020 would be the strongest in Sweden (-10.4 per cent), but also in the United Kingdom and Germany (-3.3 per cent). In Poland, the GDP would only fall by 0.2 per cent.

Losses in the adverse scenario

As of the end of 2017, the weighted average CET1 capital ratio for the group of 48 surveyed banks from 15 countries was 14.2 per cent on a fully loaded basis (and 14.5 per cent on a transitional basis). As a result of the extremely adverse conditions, by the end of 2020 the average ratio would decrease to 10.1 per cent on a fully loaded basis (10.3 per cent on a transitional basis), falling by 395 bps (or by 410 bps, on a transitional basis). In the 2016 tests, the capital ratio of the 51 surveyed banks was projected to decrease by 380 bps, to 9.4 per cent.

The banks would have to allocate their current profits to cover the losses and, at the same time, their total risk exposure amount (REA) would increase by EUR1,049bn, which would result in an increase in the capital requirements by 160 bps. However, the REA increase would mainly be driven by the increase in the risk identified by the internal models of banks using the internal ratings‐based approach (IRB). As a result of these circumstances, the CET1 capital would shrink by EUR226bn (EUR236bn according to the transitional approach).

The SSM calculated that for 33 banks from the 9 Eurozone countries, the average CET1 ratio in the adverse scenario would fall to 9.9 per cent, compared to a 8.8 per cent fall in the 2016 tests. At the same time, the average CET1 in this scenario ratio would be reduced by 380 bps, compared to a 330 bps reduction in the previous edition of the stress tests.

At the starting point, i.e. at the end of 2017, the CET 1 capital ratios in the group of the surveyed banks varied substantially — from 10.8 per cent in the case of Santander, or 11.6 per cent in the case of Unione di Banche Italiane, to 41.6 (41.7) per cent in the case of the development bank of North Rhine-Westphalia NRW Bank. The extremely adverse conditions led to a decrease of 6.4 per cent of the CET1 ratio in the case of Barclays, and to a 7.1 per cent fall for Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale, while NRW would still have the highest ratio of 34 per cent.

In this edition of the stress tests, the impact on the leverage ratio (LR) was also calculated for the first time. In the adverse scenario, the weighted average leverage ratio would fall from 5.4 per cent at the end of 2017 to 4.4 per cent in 2020, as a result of the reduction in Tier 1 capital in relation to which it is calculated. In 2018, the minimum leverage ratio above the required threshold of 3 per cent would not be reached by two banks, and three banks would not reach that threshold in subsequent years.

At the end of the surveyed period, the weakest capital ratios were reported by the Italian Banco BPM (6.67 per cent), the British Barclays (6.37 per cent) and Lloyds (6.8 per cent), as well as Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale (7.07 per cent). Other institutions that performed poorly in this regard included Italy’s Unione di Banche Italiane (7.46 per cent), whose results turned out to be significantly worse than three years ago, as well as the Spanish Banco de Sabadell (7.58 per cent) or the French giant Societe Generale (7.61 per cent).

However, even in the case of the weakest institutions, the scale of the depreciation of capital and the final indicators are somewhat more favorable than results for banks most exposed to risk in previous tests. One success story, for example, is the case of the Allied Irish Banks, whose capital decreased by 847 bps, to 6.38 per cent, in the test three years ago, and fell by 565 bps, to 11.83 per cent, in 2018 exercise. Nevertheless, it can be expected that banks with ratios significantly below 8 per cent will be subject to special supervisory attention within the context of the SREP supervisory activities.

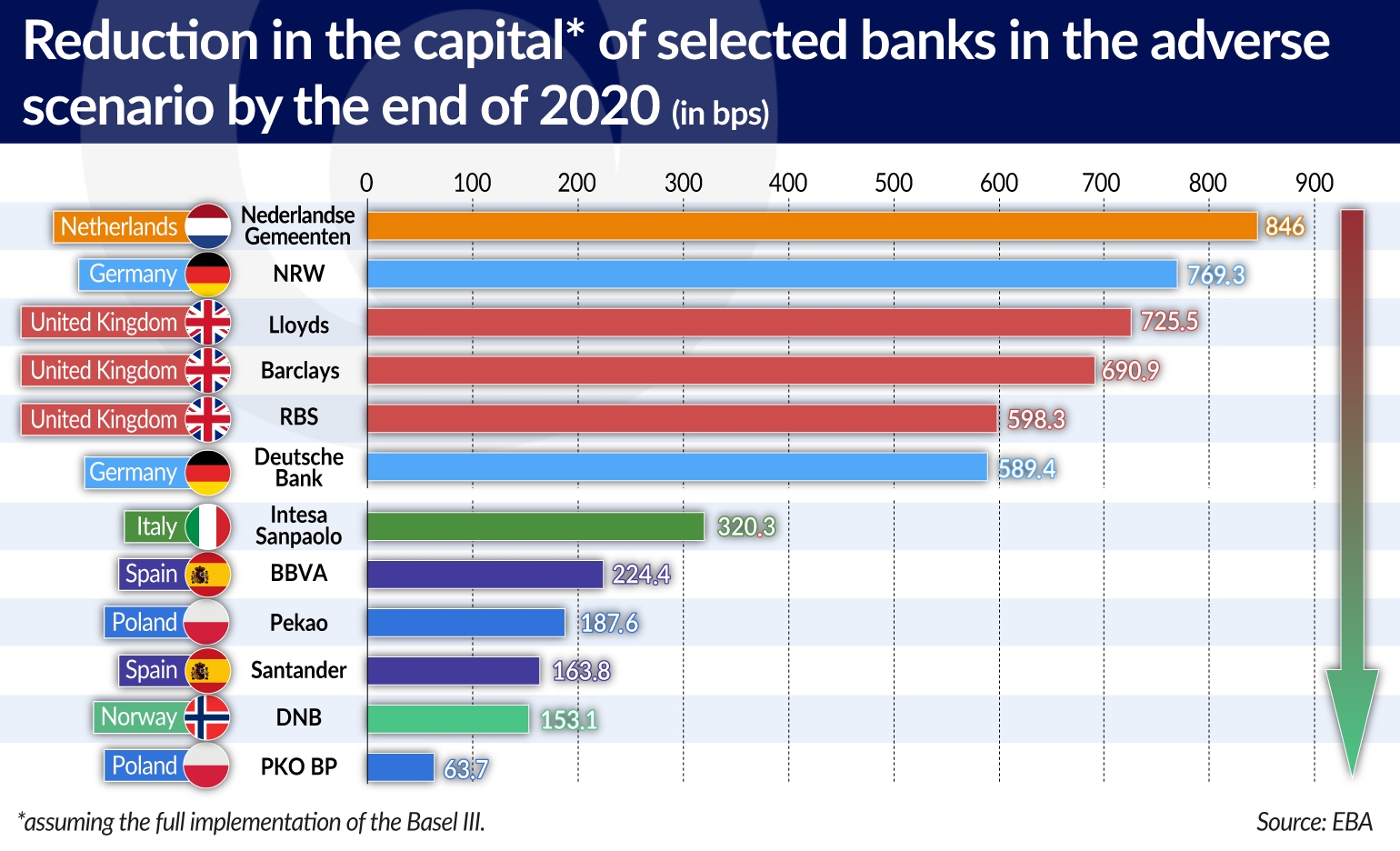

Aside from the aforementioned German public bank NRW, and the Dutch bank Nederlandse Gemeenten which is also state-owned (both had the strongest capitalization among the surveyed institutions, and at the same time both would suffer the largest reduction in CET1), the greatest decrease in capital would occur in the UK’s banks. In the tests, the capital ratio decreased by 726 bps at Lloyds, by 691 bps at Barclays, by 598 bps at the Royal Bank of Scotland, and by 532 bps at HSBC. This poses a real challenge for the Bank of England, especially when faced with Brexit.

Other institutions with the highest capital shortfalls were German banks which are at least partly owned by public authorities: Bayerische Landesbank (decrease by 585 bps), Landesbank Hessen-Thüringen Girozentrale (by 523 bps), Landesbank Baden-Württemberg (by 498 bps) and Norddeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale (by 485 bps).

The performance of Deutsche Bank was the most worrying. In the exercise, its end-of-2020-CET1 capital ratio fell by 589 bps to 8.14 per cent. Three years ago, the decrease in capital was lower, and amounted to 540 bps, but caused the bank’s CET1 capital ratio to fall to 7.08 per cent. This means that Deutsche Bank is still very vulnerable, but clearly stronger. In 2018 tests, Commerzbank’s capital decreased by 419 bps, to 9.93 per cent, while in the previous edition its capital shortfall was 636 bps to 7.42 per cent. A significant improvement has been made in this case.

The two Polish banks performed very well in the tests, and PKO BP even boasted that it had been recognized as “the most resilient bank in Europe”. Indeed, in the adverse scenario that bank’s CET1 capital ratio only fell by 64 bps (57 bps), to 15.62 per cent (15.93 per cent), which was the lowest decrease among all the surveyed institutions. In the tests carried out three years ago, the reduction in PKO BP’s capital was much greater and amounted to 198 bps.

Meanwhile, Pekao performed slightly worse, although it achieved a result placing it among the EU’s most resilient banks to recession. In the exercise, the bank’s capital fell by 188 bps (94 bps) to 14.55 per cent (15.71 per cent). However, in the conditions of Poland’s very moderate recession, its losses would be quite large — in adverse conditions they would amount to EUR257m in 2018, after which the bank would become profitable again.