Poland’s central bank, NBP, announced the launch of an asset purchase program in the framework of structural open market operations. Based on the ongoing public debate, one could get the impression that this program, commonly referred to as “Polish QE” (quantitative easing), is still generating a lot of questions and doubts. However, before we formulate any opinions, it is necessary to get a good understanding of the central bank asset purchase program and the ways in which it affects the economy. Such an approach will allow us to dispel at least some of the concerns that arise.

Polish QE and its mechanisms

The structural open market operations asset purchase program announced by NBP consists of regular purchases of Treasury bonds (T-bonds) or government-guaranteed bonds on the secondary market. This means that the Treasury securities may be also purchased from banks, and not directly from the Ministry of Finance. In practice, NBP pays the banks for the bonds with newly-created money, transferring the appropriate amount to the account that commercial banks hold at the central bank.

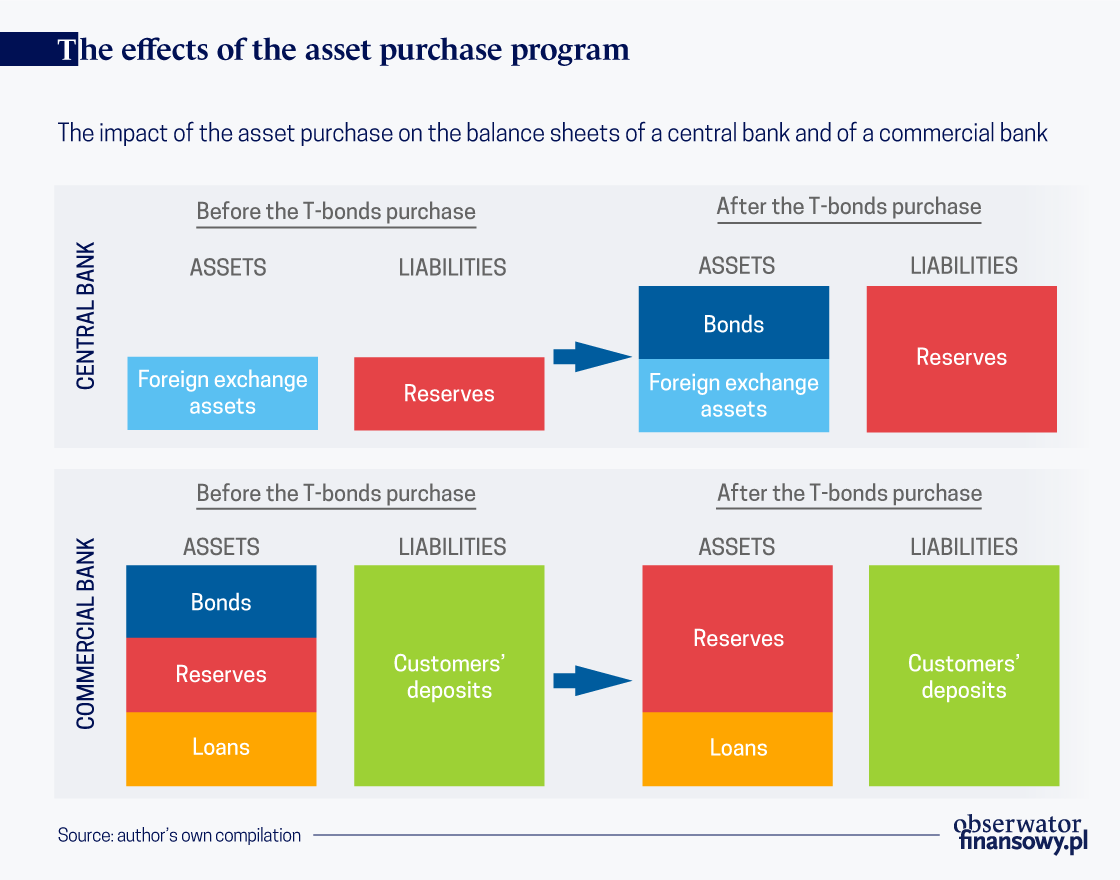

The automatic consequence of the purchase of bonds by the central bank is an increase in its balance sheet. NBP’s assets are increased by the value of the purchased bonds, and NBP’s liabilities are increased by the same amount of the newly-created reserve money. Reserve money, or simply put “reserves”, is money that is used for settlements between banks. This operation does not increase the balance sheet of a commercial bank, but it changes its structure. The side of the liabilities remains unchanged, and on the side of the assets there is a decrease in the value of Treasury securities and an increase (by the same amount) in the value of reserves held in the bank account.

Why would the central bank launch an asset purchase program?

Asset purchase programs are introduced by central banks in conditions of serious shocks, especially when the interest rates are approaching zero and cannot be lowered any further. In such a situation QE is supposed to minimize the decline in GDP and inflation. This goal can be achieved through several channels. Firstly, bond purchases lead to a reduction in market interest rates and at the same time they encourage investors to reach for new assets. Secondly, QE may indirectly lead to increased lending activity, by lowering the interest rates on loans and in some cases leading banks to seek riskier assets (that is, to grant loans). Thirdly, QE could lead to currency depreciation, which promotes exports. Finally, the central bank’s actions have a signaling function — they can increase the confidence of consumers, businesses, and investors that the central bank is serious about its tasks (the “whatever it takes” effect).

In the current crisis, the asset purchase programs applied by the central banks have one additional effect, which could prove crucial. They facilitate the financing of large fiscal programs aimed at stimulating economic growth. Most economists agree that in conditions of a pandemic, fiscal policy can be much more effective than monetary policy. In this situation, the role of the central bank is, among other things, to ensure that the financing of the stimulus programs will not lead to destabilization in the markets and that it will not threaten the stability of the financial sector. Without the involvement of the central bank, the implementation of the fiscal stabilization efforts would be much more difficult (read more).

But are asset purchase programs effective? When it comes to the effectiveness of QE/structural open market operations, the available empirical studies show that in the past similar activities had a significant positive effect on GDP and inflation, raising the paths of both these indicators and shortening the periods of recession and deflation. These studies covered the world’s largest central banks, including the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of England. Of course, each QE program is different and the conclusions from past programs, and in particular those implemented in developed countries, may not fully apply to Poland in the conditions of a pandemic. However, it is possible to state that out of the currently available instruments, the asset purchase program is probably the best option in the field of monetary policy.

Are structural open market operations something extraordinary?

Although asset purchase programs are theoretically classified as unconventional actions, over the last ten years they have actually become a mainstream monetary policy instrument used by many central banks. Even if most banks are reluctant to reach for such tools, they no longer raise major controversies. Among the largest central banks, QE programs were used by institutions such as the United States Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan. In Central and Southeast Europe such instruments were used, for example, by the Hungarian National Bank. The list of central banks that do not use some form of “unconventional” monetary policy instruments is actually much shorter than is commonly believed.

Is this policy equivalent to “printing money”?

Perhaps the most common misconception associated with asset purchase programs is treating such policies as “printing money”. Firstly, in contemporary times the central bank does not create money by using the printing presses, but simply by increasing the amount of money (reserves) in the system with a single click of a button on a computer. In other words, the reserves are created out of thin air. Printers and paper are not necessary. Secondly, and more importantly, the creation of reserves is the basic element of monetary policy operations and there is nothing extraordinary about this. For example, keeping interest rates at the appropriate level is associated with continuously controlling the level of reserves through open market operations. Without changes in the reserves in the banking system, the central banks wouldn’t be able to perform their key functions.

Do structural open market operations increase the money supply?

Asset purchases increase the amount of reserves in the interbank system and thereby increase the supply of reserve money (usually denoted as “M0”). However, this monetary aggregate only includes cash and bank reserves, and thus has little to do with what most people have in mind when they speak of “money supply”.

The broadly defined money supply (M2 or M3) also includes — in addition to cash — the current and term deposits held by customers in commercial banks. This aggregate includes the funds that can be used for payments between companies and households, while reserves can only be used for settlements between banks. Both these measures of money supply belong to different categories and are used to measure something entirely different — for example, the reserves cannot be moved outside the interbank system and cannot be further lent out to bank customers. Therefore, launching an asset purchase program and increasing the banks’ reserves has no direct effect on the broadly defined money supply. The size of money supply is not directly dependent on the actions of the central bank, but on the lending activity (in reality, the granting of a new loan creates new money).

However, one of the objectives of asset purchases is undoubtedly to stimulate economic activity and to lower the interest rates on loans, which could in the long run lead to an increase in lending activity and in money supply. Nevertheless, this relationship is indirect and does not occur automatically. If the broadly understood money supply starts to grow faster (or, at least, will not decrease) as a result of the introduction of structural open market operations, then that will be a sign of the asset purchase program’s success, and not an adverse side effect.

Will the inflation spiral out of control?

One of the common concerns presented by commentators is that the central banks’ asset purchase programs will lead to a significant rise in inflation. Indeed, such programs can lead to a higher inflation, which is, in fact, their intended purpose. However, fears of uncontrolled price increases seem to be unsubstantiated at this point in time.

The Polish economy experienced a very strong shock, which will most likely lead to a sharp decline in GDP and the emergence of a negative output gap reaching several per cent of GDP. This means that real GDP will remain below potential, which will increase the downward pressure on prices, and not the other way around. Therefore, the first threat that must be addressed is not so much an uncontrolled rise in inflation, but the risk of a period of deflation. As a rule, inflation rarely rises when there are large unused production capacities in the economy (e.g. rising unemployment, factories operating below their potential).

The undisputed consensus in the field of economics is that it is easier for central banks to cope with excessively high inflation than with deflation. In the first case, interest rate hikes provide a proven, albeit potentially painful instrument. On the other hand, in the case of deflation, reducing the interest rates to the required levels is not feasible, because for many reasons interest rates cannot be safely lowered significantly into negative territory. It is safe to say that if the central banks could choose between these two problems, they would probably choose high inflation over deflation. It is possible that at some later stage, after the economy rebounds and the utilization of production capacities returns to normal, we could also see inflation. However, in such a situation the central bank will be able to withdraw from its accommodative policy and use the “conventional” instruments to stifle inflation.

If we consider all the above arguments, the asset purchase program seems to be far less controversial than is often assumed. Of course, in the case of economic policy measures it is always appropriate to ask about the potential risks. However, most of these threats are not associated with the current application of structural open market operations. Instead, they relate to the possibility that in the future these instruments could be used in a manner that does not match the needs of the economy. In the current macroeconomic situation, given the necessity of implementing the fiscal stimulus measures, most economists and investors see the asset purchase program as a good move on the part of the monetary authorities. If at any point in the future the scale of such operations grows faster than what is warranted by the current needs of the economy, or if the assets purchases are continued even after the stabilization of the market situation as a way of financing budgetary expenditures, this could undermine confidence in the actions of the central bank. At this stage, however, such a risk is not seriously considered by market participants.

Piotr Kalisz is the economist at the bank Citi Handlowy, based in Warsaw, Poland.