Tydzień w gospodarce

Category: Raporty

Over a dozen such plants were constructed in just two years. Dams, roads and power plants were also built. Even today, the construction of the Central Industrial District can provide inspiration on how to conduct investment projects.

The construction of the Central Industrial District is one of the most recognizable economic successes of Poland in the interwar period, alongside Władysław Grabski’s fiscal and currency reform (read more), the construction of the Port of Gdynia (read more), and the Upper Silesia-Gdynia railway line for the transport of coal. The construction of the Central Industrial District was an enormous task, not only in the organizational but also in the financial sense. What’s more — the investments which were launched in the mid-1930s primarily for the purposes of national defense also helped boost a general economic recovery. At the same time, they did not become an unbearable burden for the Polish state. The construction of the Central Industrial District is inextricably linked with Deputy Prime Minister Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski, who is one of the historical figures with the greatest contributions to the development of the Polish economy.

The idea of building new factories, or expanding existing ones, which would produce equipment and materials for the military, and which would be located at the confluence of the Vistula and San rivers, far away from the borders of Poland’s potential war enemies (i.e. Germany and the USSR), was born within the Polish military community right after the end of the war with Soviet Russia in 1920. The plan first appeared in December 1921 in a paper prepared in the Department of Artillery and Armaments of the Ministry of Military Affairs. However, its implementation began 15 years later.

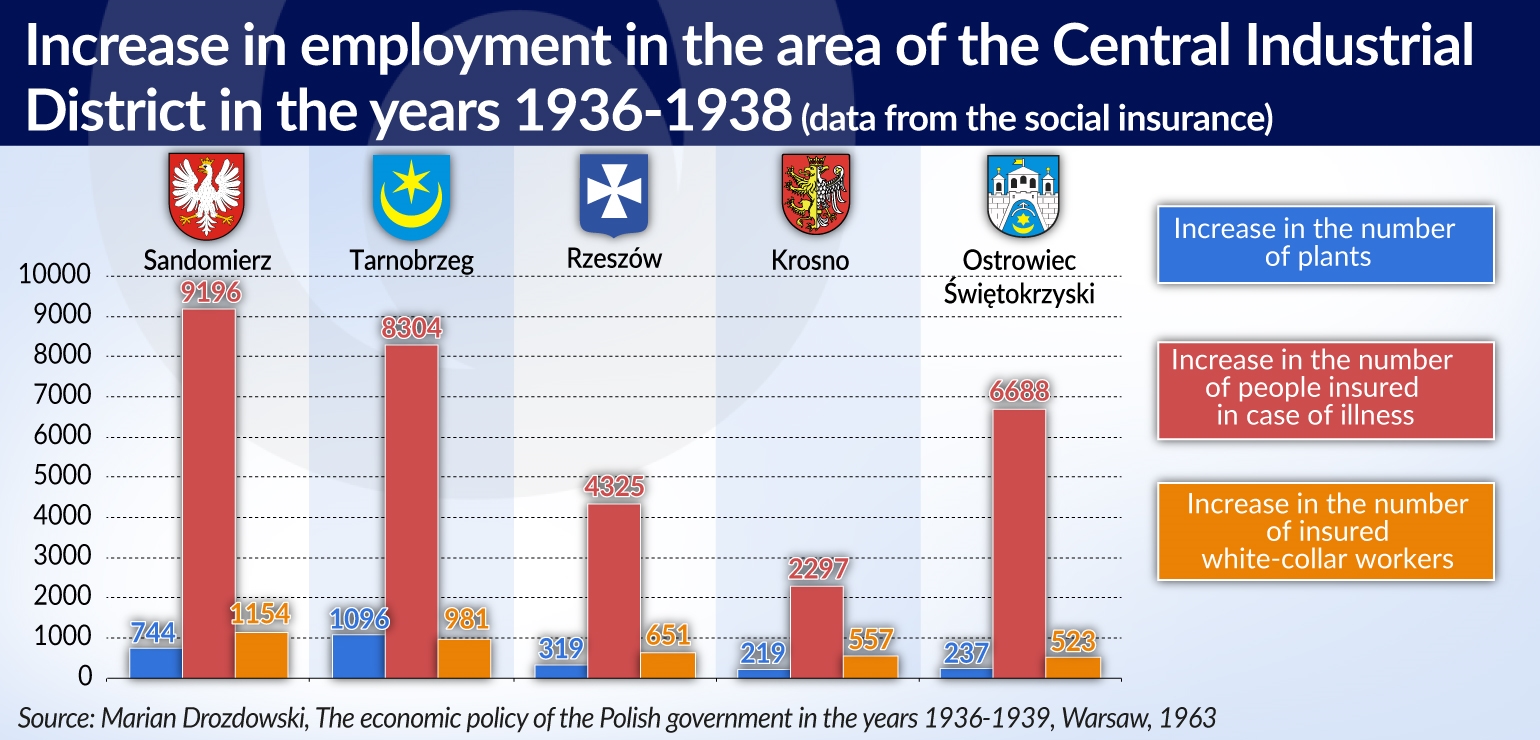

The needs of the military were the main, but not the only reason for locating the new factories far away from the national borders, in the territories of the Kielce, Cracow and Lublin regions (southern Poland) and in the western part of the then Lviv region. Such a selection was also based on economic considerations — the primary goal was to reduce the disparities between the eastern and western parts of Poland. There were also demographic reasons — due to the heavy overpopulation of the fragmented agricultural holdings, the region suffered from a significant excess of workforce. The authorities were planning to establish a separate voivodeship in this area with its capital in Sandomierz.

The first attempts to accelerate the development of investments in the “security triangle”, as the future industrial district was referred to at that time, were already undertaken in the 1920s. During the first attempt, in 1923, the plans were thwarted by the outbreak of hyperinflation. During the second attempt, in 1928, a decree of the President of the Republic of Poland determined the area of investment and indicated the available state support in the form of tax exemptions, but the practical effects were very limited. The Great Depression broke out in the United States soon after that. It rippled throughout the world and was followed by a collapse in investments and the bankruptcy of many enterprises.

The Great Depression lasted much longer in the Polish economy than in Germany, France or the United States. It was manifested by a decline in industrial production, a drop in prices and agricultural production, an increase in unemployment, and by decreases in the wages of manual workers and civil servants. The country’s economic life became largely dominated by cartels that effectively protected the interest groups and business branches from competition on a scale that would be unimaginable today. In the 1930s the number of such groups reached 300.

Meanwhile, the state ensured its tax revenues, among other things, thanks to numerous state monopolies. Outside of the spirit monopoly, there was also a salt, tobacco and lottery monopoly. In later years, a match monopoly was also created. The Polish state also owned or co-owned — directly or through the shares of the state-owned Bank of National Economy — the largest industrial plants, such as the Chorzów Nitrogen Plant, the newly built plant in Mościce, and the newly acquired Zieleniewski plant in Kraków, as well as the Ursus plant and the National Engineering Works in Warsaw.

Regardless of the circumstances governed by the overriding principle of stable money, the state finances were in a deadlock. This is understandable. The ruling elites and society as a whole were still recovering from the trauma of hyperinflation, which was only quashed by Grabski’s reform in 1924. That is why not only the center-right wing governments ruling until 1926, but also Józef Piłsudski’s Sanation camp, after the coup d’état, tried to consistently pursue a policy of a balanced budget and a positive balance of trade, although not always with success. Moreover, the strength of the Polish zloty was still based on the value of gold, despite the fact that other countries had already decided to devalue their currencies. The still young Polish state needed financial credibility.

All these elements taken together — the cartels and the monopolies in the economy, the cuts in employment and in the wages of employees, the falling incomes of farmers, the increasing tax burdens which were supposed to ensure a balanced budget, and the outflow of gold reserves and the overvalued currency — created the conditions for progressing deflation. They also encouraged greater state intervention.

In the mid-1930s various Polish economists and politicians held widely divergent views regarding the methods of overcoming the deep economic, but also social and political crisis, with divisions often running across traditional party lines.

Liberal views, including the desire to minimize the role of the state in the economy, prevailed in the ruling Sanation camp, and especially among its right-wing factions. Adam Krzyżanowski, one of the most influential economists of that time and the president of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, was one of the advocates of continuing the deflationary policy.

Orthodox free market views were also shared by the economists and politicians associated with the senior generation of the opposition National Democratic Party. The younger right-wing politicians supported state intervention in the economy, which resulted in further divisions on the right in the late 1930s. The representatives of the left-wing factions of the Sanation camp supported cautious state interventionism. Their views may have been inspired by the initial good results of Franklin D. Roosvelt’s New Deal economic policy in the United States and Hjalmar Schacht’s economic policy in Germany, both of which were implemented for the purpose of overcoming the crisis. The thought and the works of John M. Keynes, who supported state intervention in the fight against the crisis, had a significant influence on economic theory at that time.

A lively journalistic and political debate was inspired by the articles of the former Minister of the State Treasury, Ignacy Matuszewski, published in the state-owned newspaper “Gazeta Polska”. In his writings, Matuszewski was critical of the previously conducted economic policy. These discussions ultimately resulted in the development of a compromise program, which included a continuation of the deflationary policy, maintaining the value of the Polish zloty, along with significant bureaucratic restrictions on its convertibility, as well as the launch of state investment projects. This program was prepared by Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski, the Deputy Prime Minister in the last two Polish cabinets before the war, and before that the Minister of the State Treasury and the director of the state-owned nitrogen plant in Mościce, near Tarnów.

Kwiatkowski presented the concept of using investment in order to stimulate the economic recovery in June 1936 at a session of the Special Committee of the Polish Sejm for the consideration of special powers for the government. In the initial version, the 4-year investment plan provided for expenditure of the Polish zloty1.65-1.8bn. For comparison, the entire annual budget of the Polish state amounted to around the Polish zloty2bn at that time. The programe was supposed to be financed from the revenue from various state-owned institutions (the Polish zloty500-600m from fixed market institutions, i.e. monopolies, the Polish zloty150-200m from the Labor Fund, the Polish zloty300-400m from state-owned enterprises and state-owned loan institutions, and the Polish zloty200-300m from internal investment loans).

A loan of CHF400m, which Poland received from France in autumn 1936 for the purpose of enhancing the Polish military, allowed the Polish government to expand the value of the investment program to the Polish zloty2.4bn. In February 1937, Kwiatkowski presented a detailed plan of investment projects, which was simultaneously prepared by the government, as well as the Ministry of Military Affairs ,together with the General Staff of the Polish Armed Forces. The Sejm (the lower house of Poland’s parliament) then approved the implementation of the investment project, which was by that time officially named the Central Industrial District.

The construction of the Central Industrial District had to start with the development of the necessary infrastructure, and in particular the energy and transport infrastructure. The region of central Poland was very underdeveloped in this respect, and additionally — for reasons of national defense — most of the new factories were to be located far away from the existing cities. The project involved the construction of reservoirs and hydroelectric power plants in Rożnów and in Czchów, energy transmission lines and gas pipelines, as well as railway lines. Some of these lines were not built in the Central Industrial District itself, but were linked with its construction. There were plans to regulate the upper course of the Vistula and to build a waterway from Upper Silesia to Sandomierz and further along the San river to the newly built city of Stalowa Wola.

The construction of nearly 40 factories began simultaneously. Almost all of them were supposed to launch production intended for military purposes, although that did not exclude carrying out civil production as well. For example, before the World War I (WWI) the rifle factory in Radom also produced bicycles. The single greatest undertaking was the construction of the “Zakłady Południowe”, factory producing howitzers and cannons. It was a state-owned company belonging, among others, to the Society of Starachowice Mining Companies and the “Pokój” Steelworks. The construction of the factory (later renamed as the Stalowa Wola Steelworks), together with a new town for the workers, began in 1937. Production in the plant was launched a year later.

The list of new factories, as well as the timeframes within which they were completed, was impressive. An aircraft engine plant was built in Rzeszów in just one and a half years. Other plants that were built at a similarly fast pace included the airframe factory of the Polish Aviation Works in Mielec, the Chemical Plant in Dębica (today Polifarb), the Stomil Tyre Factory in Dębica, the State Munitions Factory in Kraśnik (after the WWII transformed into a bearing factory), the H. Cegielski Machine Tools Factory in Rzeszów (where the Zelmer plant was created after the WWII), the Munitions Factory in Majdan, and the Lignoza plant in Pustków (after the WWII the Erg Plastics Plant). The Zieleniewski plant in Sanok (now Autosan) was expanded to include a military division. The weapons factories in Radom and Skarżysko were also expanded.

The construction of many other new factories was also launched. The largest of these plants included, among others, the Lublin Automotive Factory, belonging to the Lilpop, Rau and Loewenstein company (the tractors and electric buses of the newly reborn Ursus company are currently manufactured there), and the Stalowa Wola Aluminum Plant.

Most of the factories (approximately 90 per cent) were owned by the Polish state. Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski had hoped for much greater involvement of private capital, but private entrepreneurs were skeptical about the fast-tracked investments that were mainly supposed to serve the needs of the military. One of the notable exceptions was the Electrotechnical Porcelain Factory launched in August 1939 in Boguchwała, near Rzeszów. It was established at the initiative of the management board of a privately owned porcelain tableware factory in Ćmielów. Another private initiative was the construction of a wire factory and a rolling mill, launched in Lublin in the summer of 1939 by the Karwina — Trzyniec Mining and Metallurgy Company, which was supposed to be erected from the components of the dismantled rolling mill in Bogumin in the Zaolzie region.

The investment plan which was supposed to last 4 years was completed within 3 years. The total expenditure for the implementation of this plan amounted to the Polish zloty2.37bn, out of which 732m was spent on energy and defense-related industrial projects, 445m was allocated on railways, 450m was spent on roads and bridges, 160m was spent on land drainage and regulation of rivers, 104m was spent on the construction of schools, and 100m was spent on postal and telecommunications projects. This expenditure was financed not only from the aforementioned sources, but also to an increasing extent using non-budgetary funds, e.g. the National Defense Fund established due to the generosity of the Polish public, and in the period right before the war also the funds collected through the national loan for anti-aircraft defense.

The construction of factories in the Central Industrial District constituted a huge financial effort for the Polish state. It can be estimated that it accounted for about a half of all investment expenditure in Poland. It also accounted for approximately one quarter of all budgetary expenditure. However, this effort did not disorganize the state finances, and — as could be feared from today’s point of view — it did not trigger inflation or a budget deficit.

Unfortunately, before the WWII these investments could not bring the desired benefits to the Polish state. When the WWII broke out production in the new factories was only just being launched. The plants were not destroyed in the military operations in 1939 and during the subsequent years of the war their production served the needs of the German occupation forces. The construction of certain facilities, such as the power plant in Rożnów and the modernization of the railway junction in Kraków, were completed during the war.

The factories of the Central Industrial District suffered more damage during the military operations in 1944 and 1945. After the war, the importance of the Central Industrial District within the Polish economy decreased. Some of the factories changed their production profile, and their ownership changed after 1989. The construction of some infrastructural elements was abandoned (for example, there were plans to extend the railway line from Tarnów to Szczucin further north towards Ostrowiec Świętokrzyski and Radom), while some of the completed projects were neglected. However, were it not for the Central Industrial District, this region would probably continue to be very underdeveloped economically.