In terms of the scale of decline, the current situation could be compared to the collapse in the foreign trade in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis. In addition to certain similarities between the current decline and the one recorded a decade ago — such as the decline in activity within global value chains and the decline in the demand for raw materials — there are also important differences. Some of them are: different initial condition of the global economy and the different nature of the shock.

While in the years 2008-2009 the slowdown in the global trade was primarily caused by demand-side factors, the current one results from a combination of both: supply-side and demand-side factors.

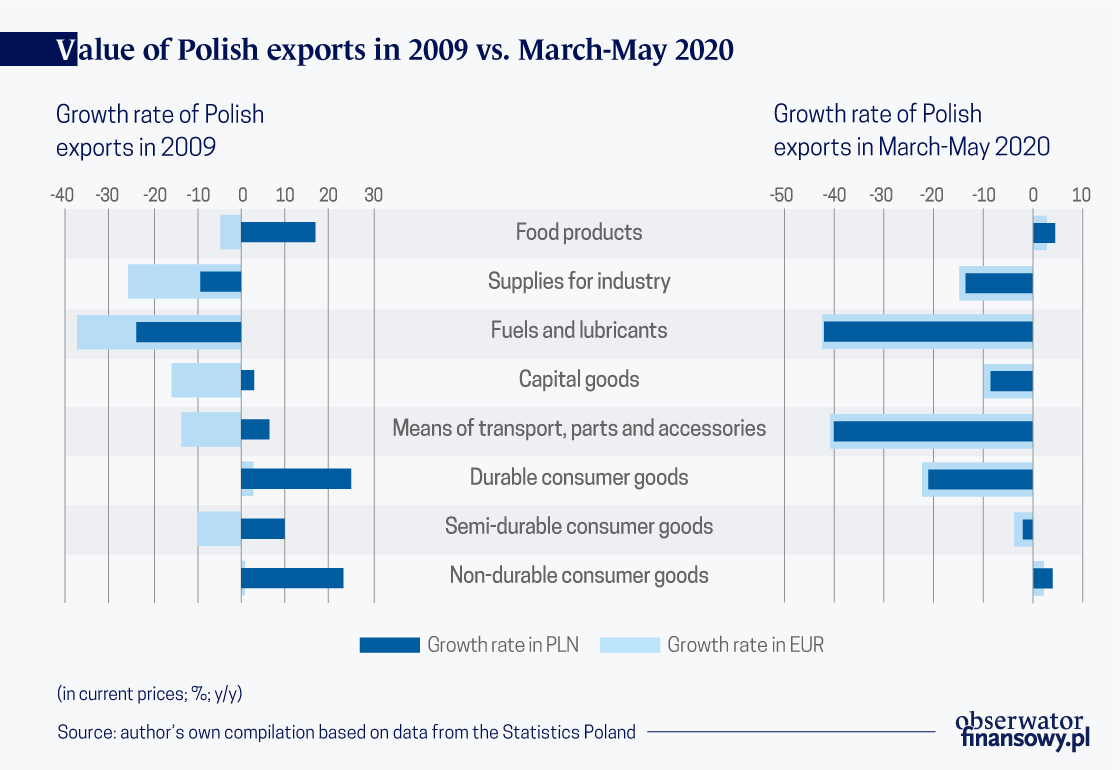

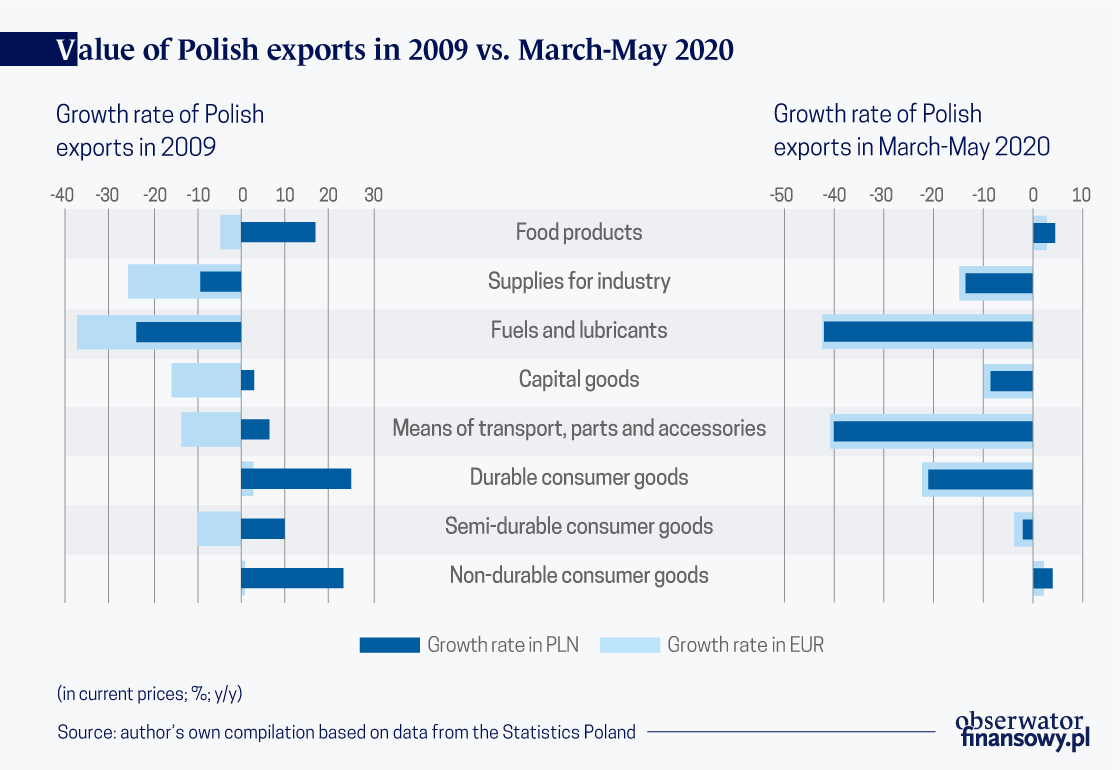

From the point of view of the Polish economy, a common feature of both discussed periods is the moderate reaction of exports of food products and non-durable consumer goods. Meanwhile, one of the factors that distinguish the current situation from the previous one is the strong reduction of Polish exports in the automotive sector.

An international perspective

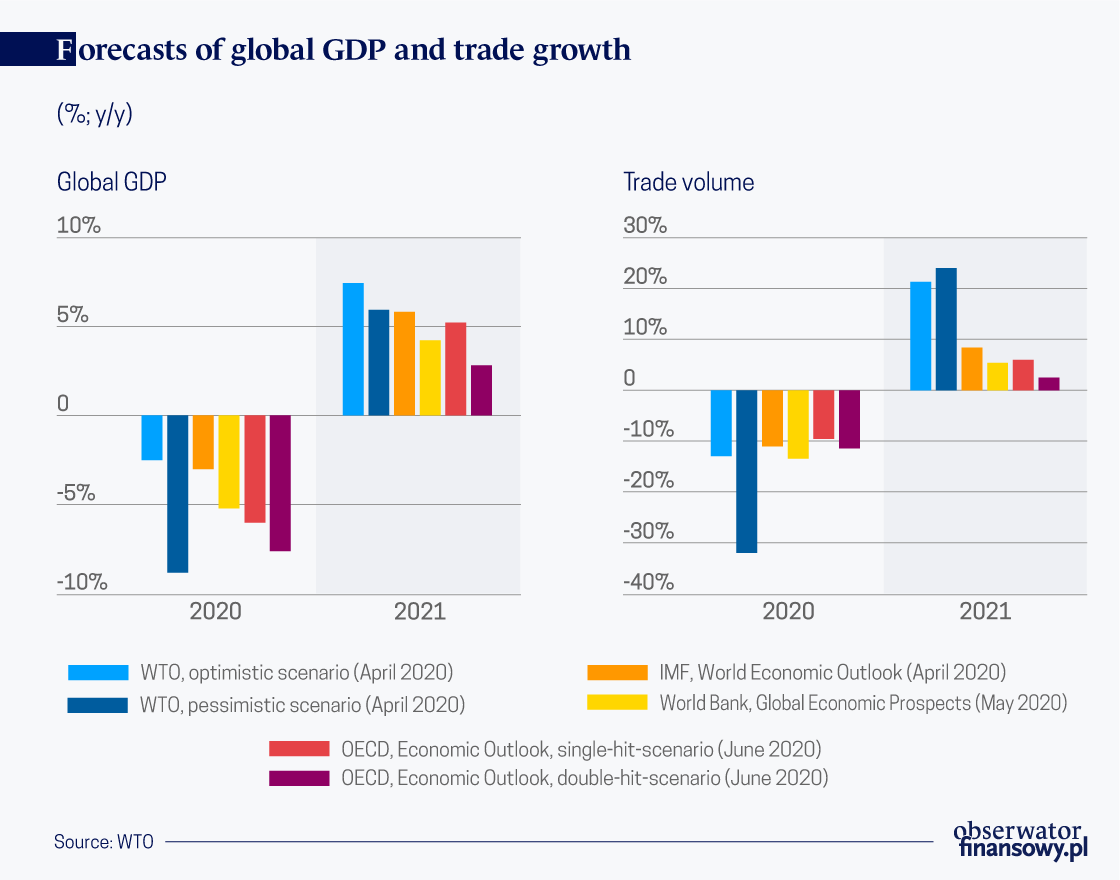

According to the forecasts of international institutions, in 2020 global GDP will decrease by between 2.5 per cent and 8.8 per cent. It is expected that the decline in global production will be followed by a deep slump in the global trade turnover.

This is because the changes in foreign trade volumes are generally stronger than changes in income, especially during recession. The most optimistic scenario, which was presented by the OECD, assumes that the decline in the volume of world trade in 2020 will amount to 9.5 per cent y/y. The biggest slump is predicted in one of the scenarios presented by WTO. According to that forecast, the volume of the global trade will decrease by 31.9 per cent y/y.

Moreover, in most of the forecasts it is assumed that in 2021 global GDP and trade volume will not fully recover to the levels recorded in 2019. It should be emphasized, however, that these forecasts are burdened with considerable uncertainty due to the constantly changing environment.

When it comes to the intensity of the observed declines, the collapse in the world trade in the years 2008-2009 could serve as a point of reference for the assessment of the current collapse. Back then, a decline was observed in the period from the Q4.08 to the Q4’09. In 2009, the volume fell by 11.8 per cent, while global GDP decreased by 1.7 per cent. It has been the biggest decline since the end of World War II. And this period is referred to as the Great Trade Collapse in the literature.

The common features of the current collapse and the one in the years 2008-2009 include the decrease in activity within global value chains (GVC) and the global decline in the demand for raw materials. The globalization has been increasing for many years, and has led to the development of strong links between imports and exports. This was due to an earlier process of international fragmentation of production.

However, cooperation within GVC is associated with exposure to strong demand shocks, which are described as the so-called bullwhip effect. This effect relates to a situation in which in response to a strong reduction in final demand the companies located at the subsequent stages of the chain decide to introduce even greater reductions in their own orders of intermediate goods and to primarily rely on the previously accumulated inventories. As a result, the scale of the decline in demand is increasing at each stage of the supply chain. Another common feature of the two analysed periods is the decline in demand for raw materials. Combined with a large increase in uncertainty, this led to a decline in the volume of trade in these products.

In the case of the current collapse, the anti-pandemic measures introduced at a similar time in the individual EU member states, led to forced production interruptions. The macroeconomic nature of the current shock differs from the situation observed in the years 2008-2009, which also has consequences for the structure of the slowdown in international trade. In the years 2008-2009 the global trade mainly slowed down due to a demand shock, and its effects were compounded in large part as a result of the aforementioned bullwhip effect.

Additionally, international trade was hindered by the original source of the shock, that is, the financial sector, whose difficult situation restricted the financing of export activities. Meanwhile, the current slowdown results from both demand-side factors and supply-side factors.

Both of the discussed periods of decline in the trade differ in terms of the condition of the global economy at the outset of the crisis. The decline in the global trade in 2009 was preceded by a period of fast economic growth and rapid increase in the volume of foreign exchange — in the years 2004-2007 global GDP grew at a rate of 4.3 per cent annually and the volume of global trade increased at a rate of 8.9 per cent annually.

The current shock has hit the global economy at a time when there were already many signs of an impending slowdown and a decline in the growth rate of world trade. In the years 2015-2019, the average rate of global GDP growth reached 2.9 per cent, and the volume of the global trade only increased at the rate of 3.4 per cent.

The decline in the ratio between the rate of growth of the global trade and the rate of growth of the global GDP may be permanent and result, among other things, from the deceleration of globalisation, as well as the increasing role of emerging market economies. They are characterized by lower trade intensity than highly developed economies — in the structure of the global trade. The increase in protectionism was additionally affecting the slowdown in the global trade growth prior to the outbreak of the pandemic. The present, less favourable situation at the outset of the crisis could therefore adversely affect the rate at which global trade recovers after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides.

The introduction of measures aimed at combating the COVID-19 epidemic caused a shock both on the supply side and on the demand side. Such disruptions have appeared already at the early stages of the pandemic, when China was still the most affected by the coronavirus. This has affected, i.a. the electronics sector due to China’s crucial role in the supplies of components to the global electronics market. Companies operating in the globalized automotive industry have experienced similar difficulties.

The introduction of restrictions along with the voluntary limitation of activity have also led to a decrease in demand, as households reduced their consumption or postponed their purchasing decisions.

Poland’s perspective

In Poland, the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 caused a sharp decline in the foreign trade turnover, but exports were less affected by the collapse than imports. In 2009, the volume of Polish exports of goods decreased by 8 per cent y/y. At the same time, the volume of imports of goods fell by 14 per cent y/y. While the scale of the decline in imports did not differ significantly from the average declines recorded in the EU, the decline in exports was much smaller compared with other EU member states.

The asymmetry in the decline in exports and imports distinguishes the 2009 from the current changes. The financial crisis was preceded by a strong appreciation of the PLN, after which a major depreciation occurred in response to the crisis (between July 2008 and February 2009 the real effective exchange rate of the PLN depreciated by 29 per cent). This significantly improved the price competitiveness of Polish exports.

Compared to the exchange rate changes occurring in the years 2008-2009, the changes observed in 2020 were relatively minor — between January and April 2020 the real effective exchange rate fell by only 5 per cent. This indicates that at present the exchange rate channel does not provide a significant shock-absorbing mechanism that would cushion the blow resulting from the decline in the demand for Polish exports.

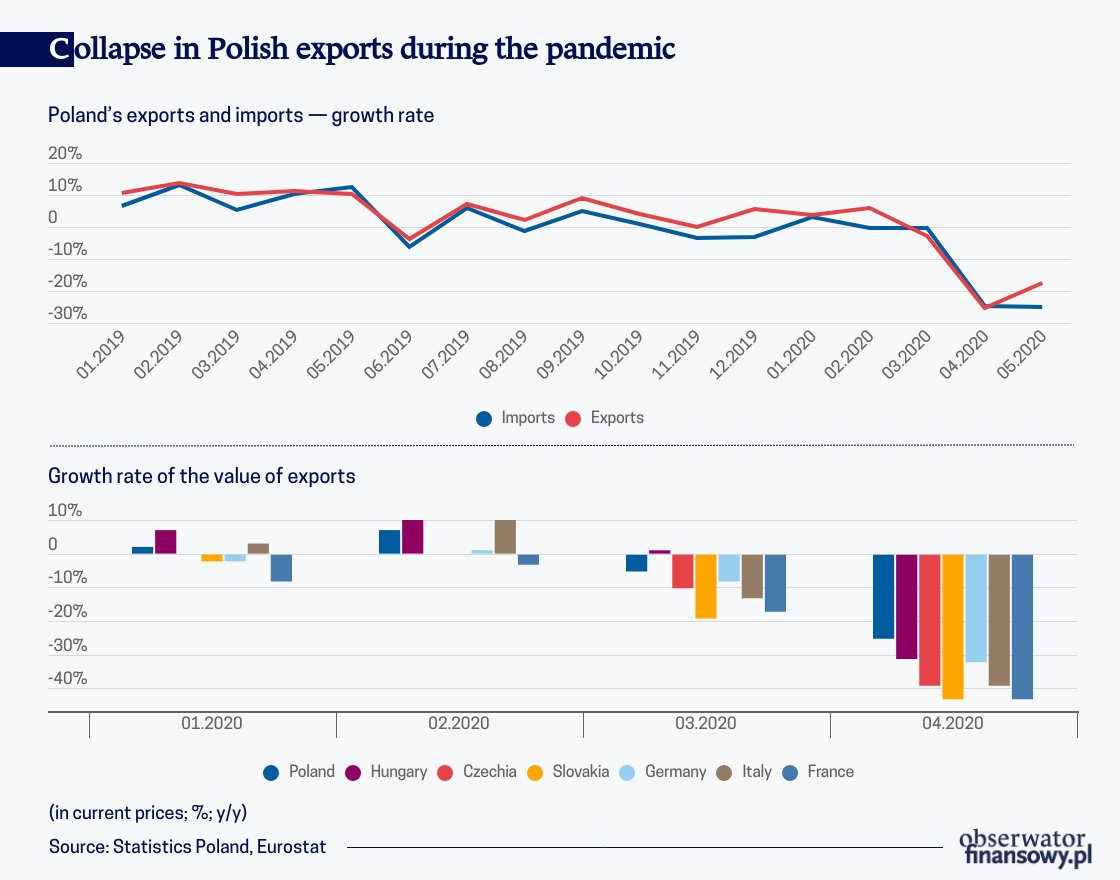

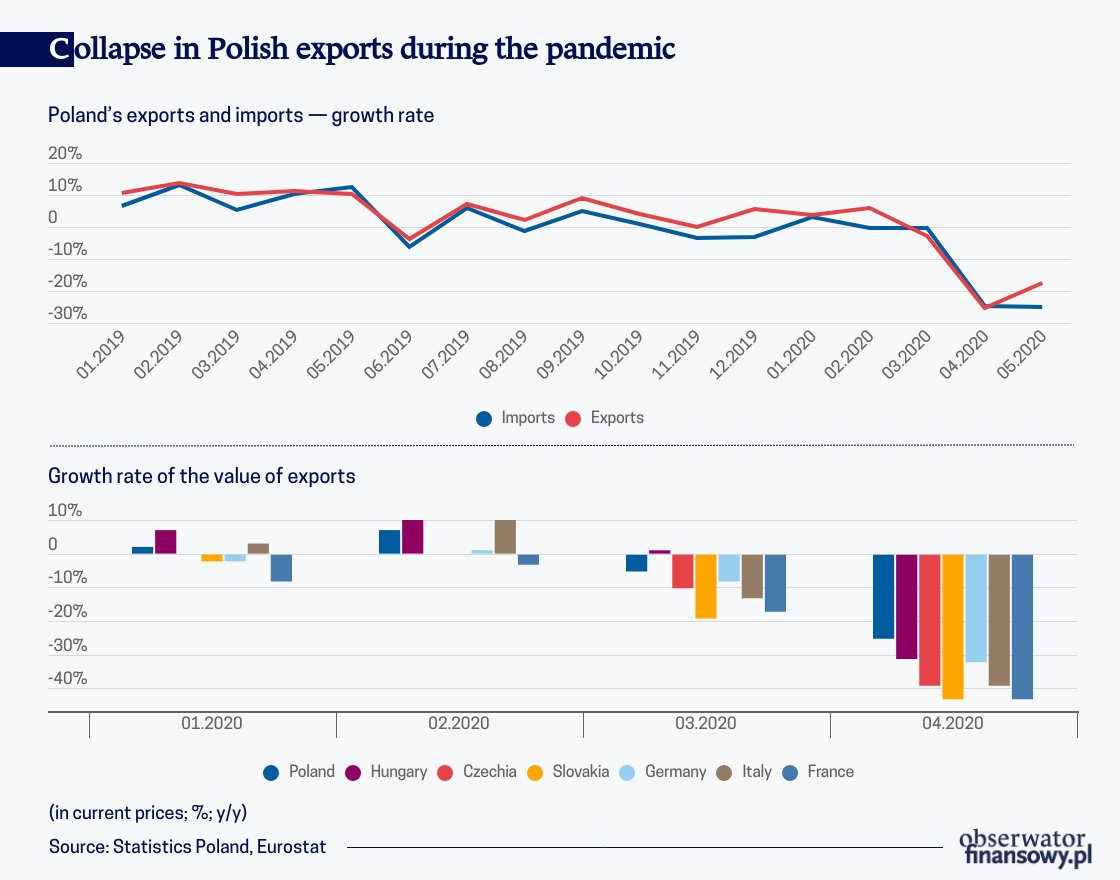

In the case of the Polish economy, the current decrease in the foreign trade turnover is less pronounced than in some other European economies. The data on the volume of Polish foreign trade for the Q1’20 indicated slight positive changes — growth in exports by 1.3 per cent y/y and growth in imports by 0.3 per cent y/y. Meanwhile, in the EU exports decreased by 2.2 per cent y/y, and imports decreased by 2.3 per cent y/y.

More detailed and recent data are only available in the current values, and thus include the changes in prices, the direction and strength of which are currently difficult to reliably measure. These data indicate a deep decline in the value of Polish exports and imports in April — in both cases by 25 per cent in relation to April 2019. Meanwhile, the data for May 2020 indicate a partial rebound in exports, which decreased by 18 per cent year-over-year, as well as a continuation of the deeply negative growth trend in the case of imports, which again decreased by 25 per cent y/y.

When compared with four other Central European countries, as well as the major European economies (Germany, France, Italy), Poland recorded the smallest decline in exports this April. The value of exports declined the most in Slovakia and in France — by as much as 43 per cent.

This suggests that Polish exports were more resistant to the shock than the exports of other countries, and this was despite the lack of a clear depreciation of the PLN. This could be explained, among others, by the fact that Polish exports are geared towards foreign final consumer demand to a greater extent than in the case of the other CEE countries, and are relatively less dependent on investment demand. Meanwhile, the collapse in investment demand was probably stronger than the collapse in consumer demand.

However, unlike in 2009, an exceptionally sharp decline was observed in the exports of means of transport, as well as parts and accessories. In addition, in the period from March to May 2020 there was a marked reduction in the value of exports of supply goods for industry, capital goods, and consumer durables.

The industry the most heavily affected by the decline in the foreign demand is the automotive sector. On average, in the period from March to May 2020, the Polish exports of motor vehicles and automotive parts were approximately 51 per cent lower than in the corresponding period of 2019. The largest drop — by 73 per cent y/y — was recorded in April 2020, while in May the decline reached 54 per cent y/y (for comparison, in 2009 the value of exports in this sector increased by 6 per cent y/y). The imports in this category also recorded a similar decline.

As a result, the automotive industry alone accounted for approximately one-third of the decline in Polish exports and imports. The simultaneous decline in exports and imports illustrates the emergence of disruptions within the global value chains.

Along with the loosening of anti-pandemic restrictions, we can expect a significant — although not complete — recovery in this sector’s exports. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) forecasts that in 2020 the number of new car registrations in the EU will decline by 25 per cent compared with the previous year.

In terms of geographical destinations, the strongest declines were recorded in Polish exports to the economies of Western Europe most acutely affected by the pandemic, and to the CEE-4. In the period from March to May 2020 a collapse was observed in the exports headed to almost all of Poland’s major trading partners, but the strongest declines were recorded in the case of Polish exports to Italy (a decline of 36 per cent y/y), Spain (a decline of 29 per cent y/y) and France (a decline of 27 per cent y/y).

Strong drops were also recorded in Polish exports to Slovakia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Although these countries were less severely affected by the epidemic than the countries of Western Europe, they are linked with Poland within the regional value chains of the automotive sector. Automotive parts are an important category of Polish exports to the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia, corresponding to 10 per cent, 13 per cent, and 17 per cent of Polish exports to these markets, respectively. The only big market in which the value of Polish exports increased in the period from March to May 2020 was China (an increase of 15 per cent y/y).

For comparison, in 2009 the strongest declines in Polish exports related to the eastern markets (Russia and Ukraine), as well as the Baltic countries. Meanwhile, the exports to the markets of Western Europe even exhibited some increases when expressed in the Polish zloty, or recorded small declines when expressed in the euro (the rate of growth in the volume of exports expressed in the PLN and in the EUR differed significantly due to the aforementioned strong depreciation of Polish currency in the years 2008-2009).

At present the prospects for a quick rebound of Polish exports seem to be more limited than in 2009. This is due to the global trend of a slowdown in globalization, the greater risk of protectionism, the occurrence of demand-side shocks alongside the supply-side constraints, as well as the forecasts indicating that economic activity in the world will not recover fully in 2021.

Moreover, in contrast to 2009, Polish exports today cannot take advantage of a similarly strong depreciation of the Polish currency. Nevertheless, one positive signal, just like in 2009, is the resilience of Polish exports in certain product categories, and especially food products and non-durable consumer goods.

Another positive signal is also the lower scale of declines in Polish exports compared with the countries of the region and the largest EU economies. This can be associated with the fact that the automotive sector, which has been particularly strongly affected during the current collapse, as well as goods satisfying foreign investment demand are relatively less important in the structure of Polish exports.

Jan Baran is an economist in the Economic Analysis Department of Poland’s central bank, NBP.

The views expressed in this article are the private views of the author and are not an expression of the official position of the NBP.