Why Has Japan’s Cash Demand Remain Strong?

Category: Macroeconomics

Economist, works at NBP, specialises in monetary policy issues and FX markets

It is therefore not surprising that central banks are increasingly turning towards non-standard monetary policy. The latter is most frequently associated with quantitative easing (QE). Many people still view QE through the prism of inflation risks, although reality seems to be indicating something different. It’s worth reminding once again that the quantitative easing generated by central banks simply fills the void left by the collapse in lending activity.

However, there are different perspectives that can be adopted with regards to the effects of quantitative easing, and especially in relation to the QE measures launched as a result of the spreading COVID-19 pandemic. We can refer to processes taking place both in the monetary aggregates, as well as in the central bank’s balance sheet.

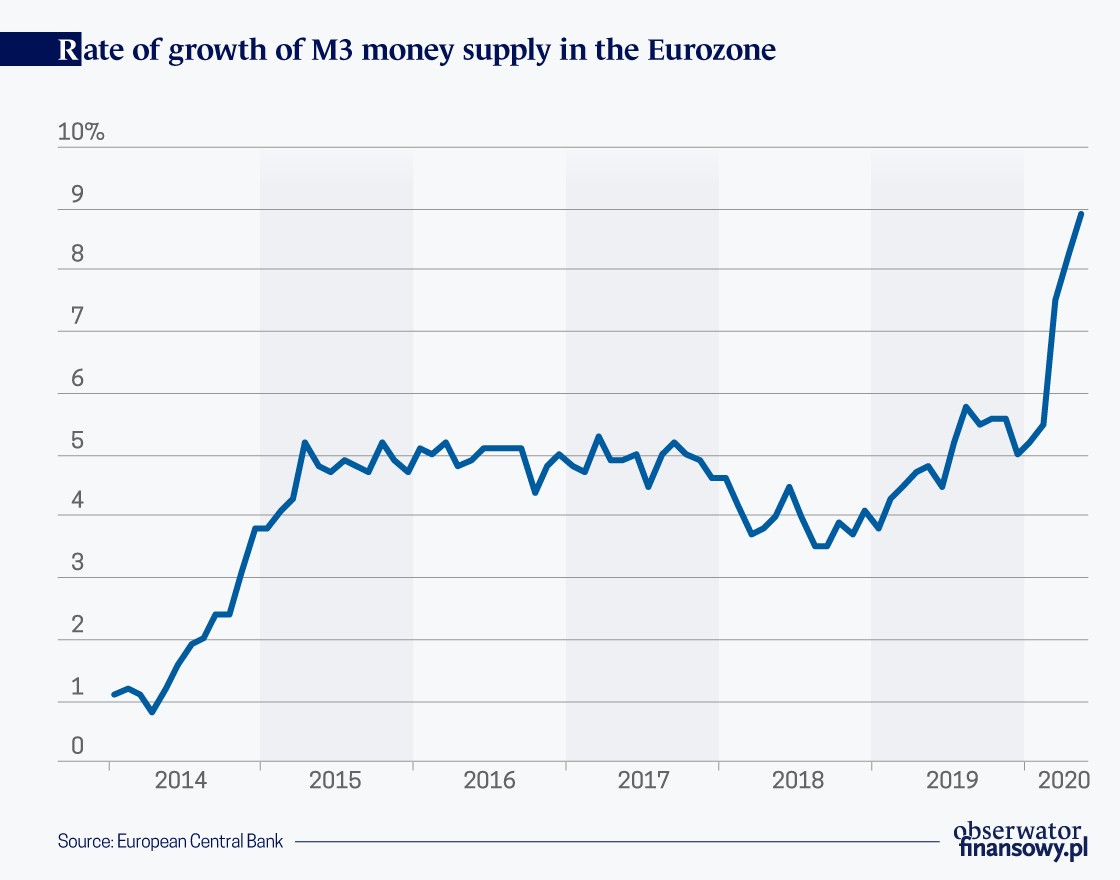

The monetary aggregates are used to measure the amount of money in the economy. They are mirrored by the money supply counterparts. By observing both sides of this equation we can notice certain interesting trends. We most frequently hear about the broadest money aggregate known as M3, which includes cash, money in the checking accounts, deposits with maturity of up to two years, deposits redeemable at a notice of less than three months, money market fund shares/units, repurchase agreements, as well as debt securities with a maturity of up to and including two years. The M3 consists of smaller aggregates: M1 (cash and money on the checking accounts), and two remaining component parts. The M2-M1 includes the two previously mentioned types of deposits, while the M3-M2 includes money market fund shares/units, repurchase agreements, and debt securities with a maturity of up to and including two years.

The monetary policy pursued in recent years is not conducive to saving money, which affects the described aggregates, and especially the increase in the weight of M1. In the past, the M1 accounted for around 40 per cent of M3, and today its share, at least in the Eurozone, is above 70 per cent. In the times of negative interest rates, very few people want to save money. They prefer to keep money in cash or in checking accounts. This doesn’t only apply to individuals, and a similar (and even more pronounced) trend is observed in the case of companies. Over the last three months we’ve seen an incredible accumulation of funds by both enterprises and households. What could be the end result of such developments?

An increase in the amount of funds on deposits could be a sign of a new trend in which people are saving more money. COVID-19 has been and remains a clear warning that a life based on borrowed money, which is so often promoted by the banks, also has its dark side. The lockdown has allowed some people to escape the endless cycle of consumption. However, not everyone is happy with this course of events.

Today’s economy is primarily based on consumption. This is the source of significant controversy. We are increasingly hearing opinions that economic growth fueled solely by consumption is not the optimal solution. Perhaps it would be a much better solution for people — once they overcome their fears about the future — to start allocating the surplus funds accumulated during the pandemic on the financing of investments or the ever-growing public debt? After all, is it possible for the latter to be indefinitely financed solely by the central banks? For the time being, there is still a chance to redirect savings towards things other than just consumption. Whether we seize on this opportunity remains an open question.

Moving on to the counterparts of money supply, it’s worth taking a look at the item entitled “net foreign assets”. The analysis of this position allows us to see who is selling bonds to the central bank — residents or non-residents. When the ECB launched its bond purchases in March 2015, it initiated a massive outflow of capital from the Eurozone, which was one of the reasons for the weakness of the EUR against most other currencies. Initially, the launch of programs aimed at fighting the consequences of the pandemic once again caused the outflow of capital. However, this only lasted until May 2020. Perhaps this is due to the fact that at present all the countries are trying to protect themselves against the negative effects of COVID-19 and fleeing the Eurozone is no longer an alternative. The situation was different in 2015. Back then, the ECB was a pariah of sorts, whose actions were lagging behind those undertaken by other central banks. At the point when the ECB was initiating the purchases of government bonds, the Fed was in fact already preparing to tighten its monetary policy. Right now, it seems that the ECB is in good company of pioneers. We should keep in mind, however, that outside of splendor and glory, pioneers are also exposed to various pitfalls associated with venturing into new and uncharted territory.

The central banks are purchasing assets, paying for them with newly issued cash. This is just jargon. In reality, the newly created funds amount to nothing more than electronic records. The purchased securities are recorded on the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet, usually under a specifically separated item. For example, the ECB calls this item “securities held for monetary policy purposes”. The money spent by the central bank on the purchase of bonds usually returns to this institution. It’s simple — commercial banks are either not willing or not able to quickly expand their lending activity and prefer to deposit the obtained funds at the central bank. The changes in the volume of funds under this item are shaped by the deposit rate set by the central banks. This brief description could lead to the conclusions that central banks have a lot of influence. But is this indeed the case?

All those who believe in the unlimited power of central banks are up for a big disappointment. The central banks don’t even fully control what happens in their own balance sheets. In reality, they only make decisions on how much loans they will grant to the banking sector and how much funds they will accept into deposit. Recently, one additional prerogative has been added — the purchase of the aforementioned assets. All the remaining items belong to the so-called “autonomous factors”. They are called this way, because due to its autonomy the central bank is not able to fully control them.

And what about the cash issued by central banks? It is also a part of the autonomous factors. It’s true that the central bank issues currency and thus controls its supply. But the demand remains out of its control. The way in which we settle our next payment depends solely on us. Whether we pay for our purchase with cash or with a payment card has an effect on the type of money used. The former is created by the central bank, and the latter is created by the banking system.

For a long time, cash was the biggest component of the central bank’s liabilities. Today, it is losing its importance as a balance sheet item. It was overtaken by the funds held at the central bank by commercial banks. However, cash still remains an important element of the liabilities, also as the largest item among the autonomous factors on the liability side.

COVID-19 has led to a strong increase in cash, but this isn’t a source of worry for the central banks, as it has all the features of being temporary. The situation was similar in October 2008. Back then, the increase in cash was also temporary and did not carry any risks.

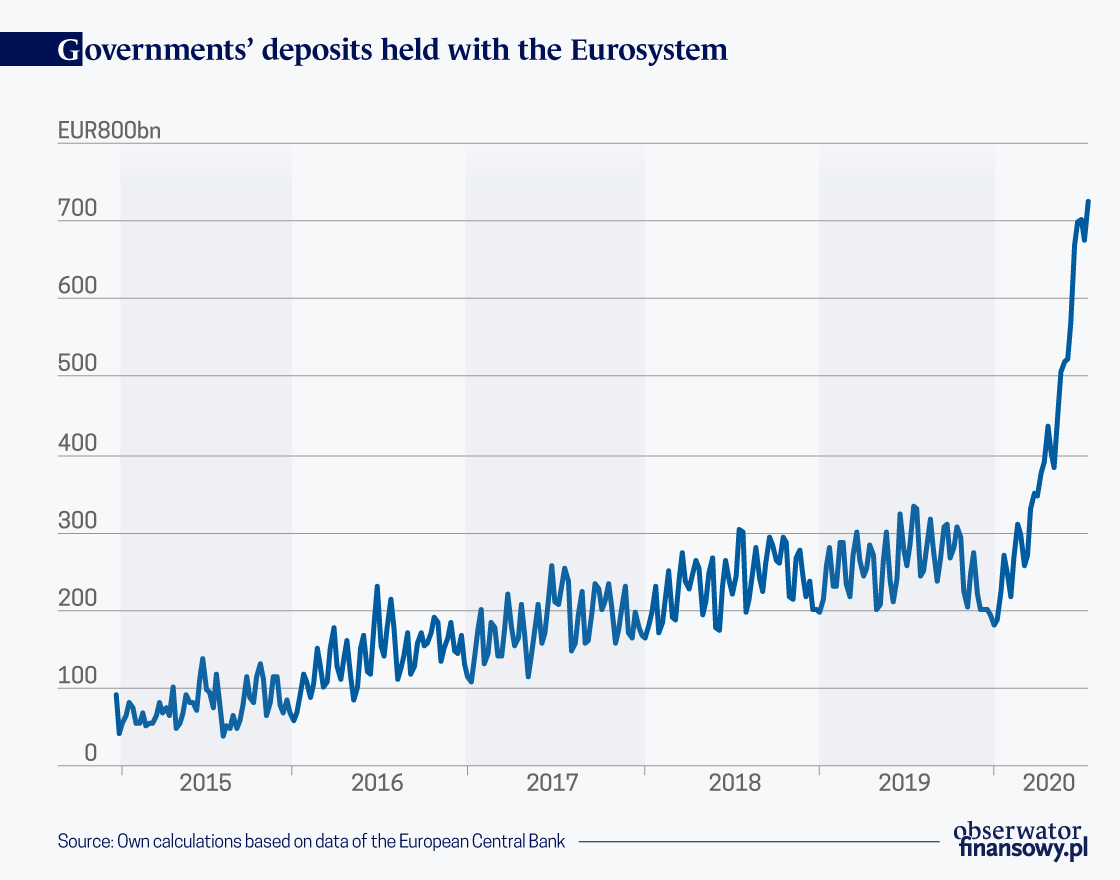

Another important balance sheet item is the funds that governmental institutions hold with the central bank. One of the tasks of the central bank is to serve as a bank for the government — at least this is what we can read in many textbooks. The volume of government funds is constantly growing, however, and the central banks may be getting a little worried. Over the years, they have gained experience with regard to cash and they are able to reliably predict its behavior. The situation is worse when it comes to government funds. Moreover, the scale of the increase is really big. Today, the German authorities are holding roughly the same amount of funds at the Bundesbank as all the Eurozone governments were holding in the Eurosystem three years ago.

This should be worrying mainly because government funds are the most unpredictable autonomous factor. It is not surprising, therefore, that central banks are trying to discourage governments from depositing money. In 2019, the ECB took special measures to encourage governments to keep the money in the market. However, in times of negative interest rates, investing in safe instruments is an expensive undertaking. In this situation, central banks seem to be a safe haven for the governments.

This raises the question, however, of whether they are not becoming a beneficiary of the close ties between the two centers of power? While back in 2014 the governments deposited an average of EUR85bn in the Eurosystem, in recent weeks the value of the deposits has often exceeded EUR700bn. This certainly doesn’t help the central bank in its conduct of the monetary policy. And after all, the more unpredictable the environment, the greater the likelihood of mistakes being made.

The views expressed in this article are the private views of the author and are not an expression of the official position of the NBP.