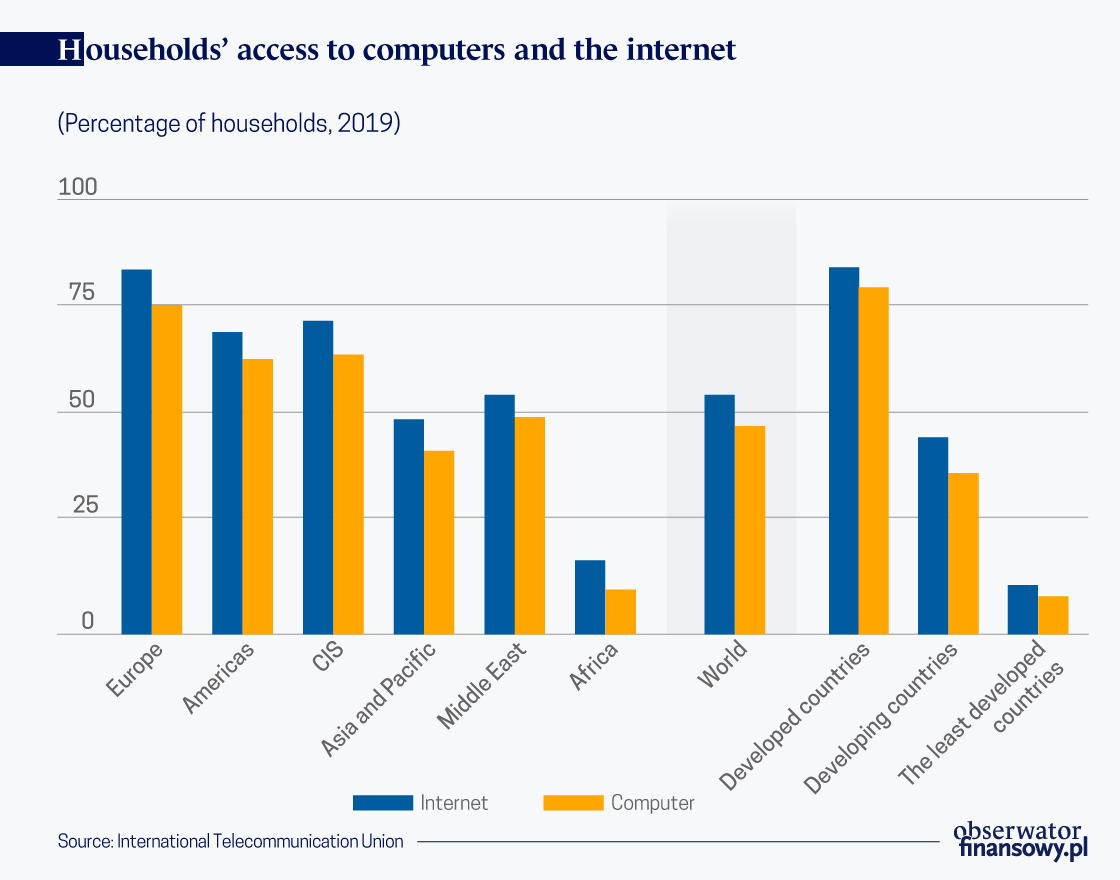

According to UNESCO, about 55 per cent of the world’s households have access to the internet. This share reaches 87 per cent in developed countries, 47 per cent in developing countries, and only 19 per cent in the least developed countries. Across the world, 3.7 billion people are still offline. Digital exclusion affects women to a greater extent — globally women are 23 per cent less likely than men to use mobile phones on average.

The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic cut off large numbers of people without internet access from basic services and social benefits. In Latin America 154 million children were forced to stop their education, because as many as two-thirds of the people on that continent do not have access to the internet and a computer in their household.

Digital exclusion is the consequence of a number of factors. The most important are the costs. About 40 per cent of the “offline population” in poor countries claim that they have never used the internet, and 35 per cent do not own a computer because they are too expensive. The Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI) classifies internet connections as affordable when the cost of 1 GB of mobile data is equivalent to no more than 2 per cent of the average monthly income. While in France and Sweden the cost of 1 GB of data is equivalent to USD3-4, and in Germany and the United Kingdom it is less than USD7, in the United States it is more than USD12. Meanwhile, in the countries of sub-Saharan Africa the cost of an hour of streaming is equivalent to 40 per cent of the average monthly income, and 85 per cent of the continent’s inhabitants currently live on less than USD5.5 a day. Many populations in the Third World live in informal settlements or slums, which are not equipped even with rudimentary digital infrastructure. These people usually work in the informal economy, earning a wage than only allows them to survive from day to day.

The social welfare programs of many countries fail to recognize people who are digitally excluded, especially considering that they don’t have biometrics-based digital identification registers like the one operating in India. The Aadhaar digital identity system has been implemented for several years. It enables the authorities to reach more than a billion people via smartphones, which is especially important in rural areas. As a result, more than 50 per cent of India’s citizens can take advantage of government assistance.

Large parts of the populations in Kenya, Thailand and Egypt also benefit from digital transfers. During the pandemic, the west African country of Togo only needed two weeks to launch cash transfers for half a million of its poorest inhabitants, especially women. Similar aid was provided to the poor and to those employed in the informal economy in Morocco. Since the outbreak of the pandemic up to 80 per cent of the assistance funds in sub-Saharan Africa were made available in the form of cash transfers. Funds can also be paid out at mobile money agents operating in many developing countries. For the residents without smartphones it was far more difficult to receive these funds, if only due to the considerable distances from the nearest bank branches. It should be added that 1.7 billion people across the world still remain unbanked and do not have an account at any official financial institution.

The digital gap doesn’t only affect developing or underdeveloped countries. It also impacts a number of people in the developed world, like in the US. According to the report of the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation from December 2019, more than 98 per cent of Americans have access to broadband, high speed internet, but more than 20 million still did not use such services as of the end of 2017. In their report, the senators also highlighted the differences between urban areas, where 98.3 per cent of the people have access to broadband internet, and rural areas, where that share is 73.2 per cent. The situation is even worse in Tribal areas — only 67.6 per cent of people have high speed internet. As a result of the limited access or lack of access to the internet people are unable to take advantage of telemedicine, remote learning, or to effectively conduct business activity or run a farm.

In Australia 2.5 million citizens do not use the internet, and 1.3 million households have no internet connection at all. Meanwhile, 12 per cent of Australians do not have access to broadband internet. In Europe, 85 per cent of adults used the internet in 2019. Out of that group, 71 per cent shopped online, and 61 per cent used online banking. However, as many as 9.5 per cent of EU citizens have never used the internet.

According to the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), the highest rates of use of internet services are recorded in Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark and the United Kingdom (nearly 90 per cent). Meanwhile, the lowest rates are recorded in Italy, Romania, and Bulgaria (30-40 per cent). Another important issue is the rate of access to digital public services (collectively referred to as “eGovernment”). The best results are recorded in Estonia, Spain, Denmark, Finland, and Latvia, where more than 85 per cent of internet users also access such services. Meanwhile, Romania, Croatia, Greece, Slovakia, and Hungary are doing much worse. In these countries the rate of usage of digital public administration services is lower than 60 per cent (for comparison, in Poland it is 68 per cent), while the EU average is 72.2 per cent.

At the beginning of the pandemic the Capgemini conducted a survey of the offline population (aged 18-70) in several countries. It turns out that the largest share of offline population are people aged 22 to 36. More than half of them had to give up on using this medium — many did so after completing their academic education, especially those living in rural areas (47 per cent). Even in the EU member states we see a big difference in internet use between the cities (88 per cent) and the rural areas (62 per cent). The main reasons for this include financial status (for more than 50 per cent the internet or smartphones are too expensive) and the availability of a broadband connection. The representatives of other age groups and people with disabilities declared that the internet was too difficult, or claimed that they simply weren’t interested in using it — this was particularly true for people aged 60 and older (57 per cent of people in this age group). Nearly two-thirds of these respondents have never used the internet and do not intend to use it.

A large proportion of digitally excluded people are aware of the missed opportunities and chances. They believe that internet access could improve their contacts with friends and family (46 per cent), make their life easier (45 per cent), and enable them to educate themselves and find better jobs (44 per cent). Other advantages include the ability to buy cheaper products and to better fulfil one’s financial obligations (42 per cent), as well as giving them easier and faster access to social benefits (42 per cent). As many as 40 per cent of digitally excluded people claim that with the internet, they would be able to provide better opportunities for their children. It’s worth noting that only 19 per cent of respondents living in poverty received any social benefits in the year preceding the survey.

During the pandemic, the situation could be even worse, because the digitization of many spheres of social and economic life has become a discriminatory factor. According to a study conducted in France, the dematerialization of public services has led to a decline in the number of applications for driving licenses as well as the number of submitted job applications. On the other hand, the British Good Things Foundation reports that active internet users save GBP 744 per year by buying cheaper goods and taking advantage of various promotions. Meanwhile, the American think tank Phoenix Center published a study according to which internet users aged 55 and more are 20 per cent less prone than their offline peers to mental illness and depression.

Many governments, cities and organizations have been implementing initiatives aimed at combating digital exclusion for a number of years. In Germany so far nearly 1500 initiatives have been created to increase the level of digital literacy, especially among older people. Since 2013 this objective has been implemented through the program “Senior Technology Experts”. Meanwhile, the “Digital Day 2020” was celebrated in mid-June. These activities are supposed to prepare the public for the full digitalization of public services in 2022. The French government is implementing a digital inclusion program addressed to 6.7 million people who have not been using the internet thus far. A similar project is implemented in the United Kingdom, where plans are put into action to connect 15 million households to broadband internet by 2033.

The development of digital skills, also among people with disabilities, is supported by technology companies like Google and Microsoft, as well as banks. Barclays awards prizes in order to encourage people to teach the use of the internet to their friends and neighbors. For several years, the city of Medellin — known years ago as the center of the Colombian drug cartel — has been implementing a program to popularize digital health care and educational services among the excluded communities by offering free internet access in libraries. Meanwhile, the mayor of the city of Bogota has recently announced a plan to provide free Internet access to 100.000 poor families with children by the year 2024.

Many ad hoc activities aimed at combating digital exclusion have also been undertaken during the pandemic. Numerous central government and local government authorities have financed free tablets (e.g. in the United States, Peru, Australia, of the city of Recife in Brazil), exempted people from internet access fees or from charges for the use of medical and educational sites (e.g. in the United States, South Africa, Peru).

The accelerating, also due to the pandemic, process of digital transformation means that access to the internet is becoming one of the basic commodities and may soon be recognized among fundamental human rights. UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and the ITU (International Telecommunication Union, which is a specialized agency of the United Nations) established the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development whose goal is to connect 75 per cent of the global population to the internet by 2025. Without broad-based and systematic activities, access to the internet and digital skills will become yet another key factor of polarization in the world.