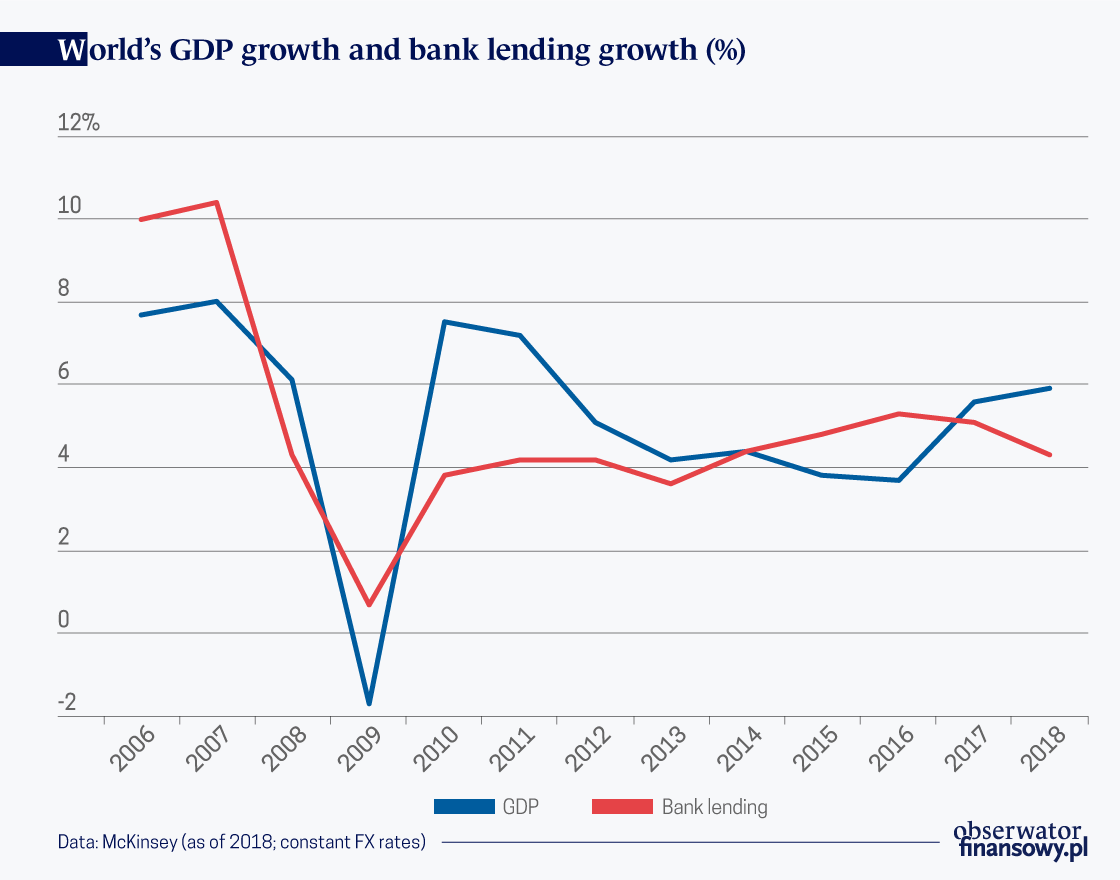

Most banks don’t have too many reasons to be satisfied. In the years 2017-2018 the rate of increase in loan volumes and revenues was 1.5 percentage points lower than the rate of GDP growth. Moreover, 60 per cent of banks examined by McKinsey reported returns on assets lower than the cost of equity, even though the risk costs are at an all-time low thanks to advanced analytical tools and artificial intelligence solutions.

Falling profit margins

The near-zero or even negative interest rates certainly do not improve the banks’ situation, because the margins are constantly falling, from 234 basis points (bps) in 2013 to 225 bps in 2018 in developed markets, and from 378 to 337 bps in the emerging ones. Only 102 of the 595 studied entities managed to improve their cost-to-income ratio (C/I).

The banks’ results are strongly correlated with three factors — location, the scale of operations and the adopted business model, which affects revenue generation and productivity, as well as the outsourcing of processes that do not provide a competitive advantage. As much as half of the banks’ costs are directed towards activities that do not provide a competitive advantage and do not differentiate the given organization from its competitors.

Four segments of banks

The “market leaders” (20 per cent of banks globally) are entities that capture nearly 100 per cent of the economic value added in the entire banking sector. They operate on broad, global markets and in favorable market conditions, like many banks in the United States, whose returns on equity are 10 percentage points higher than those of their European counterparts.

The “resilient” (25 per cent) are largely European banks that operate in a less favorable environment, with lower GDP growth rates and low interest rates. They require greater scale and innovation that will enable them to reach new customers.

The “followers” (20 per cent) are entities that have not reached sufficient scale of operations and should reduce costs and change their business models in order to survive.

Lastly, the “challenged banks” (about 35 per cent of banks globally) that may need to merge with similar banks in order to achieve the required scale of business operations, or that might be taken over by a stronger player.

The digital revolution

An important challenge for most of the traditional financial entities is the continuation of the digital revolution which leads to changes on the supply side, that is, the emergence of new players that are biting into the banks’ margins, targeting the market segments responsible for 45 per cent of the banking sector’ revenues. This, in turn, leads to changes on the demand side — in the behavior of consumers.

On a global scale the use of online financial services has increased by over 13 percentage points since 2013 and there is still much room left for further growth. However, it seems increasingly unlikely that banks will be the beneficiaries of this process. As a result of digitization customers are also becoming less loyal, because it is very easy to switch the service provider.

Banks are seeing the loss of customers in the retail banking segment, where loyalty used to be high. In the US in five years the rate of customer attrition increased from 4.2 to 5.5 per cent, and in France it rose from 2 to 4.5 per cent in 2017.

This problem could be exacerbated further, as consumers are increasingly confident in big technology companies and are willing to entrust them with the management of their finances. This applies to companies such as Amazon (indicated by 65 per cent of respondents) and Google (58 per cent). This is also a reflection of the growing belief that all banks are alike — such an opinion is shared by one-third of American internet users.

Open banking

Competition between banks and technology companies will become even more intense due to the progressing implementation of “open banking” regulations, which are being rolled out in a growing number of markets. Simply put, these regulations enable non-bank entities to access the financial data of bank customers and to use these data to develop new products for them (also including non-financial products).

This applies to the greatest extent to the countries of the European Union (the PSD2 directive) and the United Kingdom, which implemented “open banking” regulations at an earlier point. In 2018, the number of new players on the British market grew by 65 per cent, and in August 2019, there were already 143 entities authorized to utilize the features of open banking pursuant to a license from the Financial Conduct Authority.

In Australia “open banking” was introduced in February 2020, and a year and a half later it is supposed to apply to data covering virtually all products of a given customer, including mortgages, as well as leasing and investment products.

Countries such as Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Brazil, Singapore and Canada are also preparing to liberalize the banking market. Meanwhile, the United States, New Zealand, Chile, Nigeria, Kenya and Rwanda are less advanced in this regard. According to the German company Ndgit, providers of API platforms allowing for the exchange of data among the entities participating in open banking are already functioning in more than 50 countries, connecting more than 10 thousand banks with third-party providers. This indicates, that the principles of “open banking” are fast becoming a global phenomenon.

Many banks are not prepared for such a revolution, even though some of them are likely to become its beneficiaries. This is the case in Poland, where the level of digitization of the banking industry is already high and the process of issuing licenses to external operators is proceeding rather slowly.

Asian banks feel most threatened by these developments. In that region only 20 per cent of banks declare that they are prepared for this transition. This is also due to safety reasons and the lack of common standards in the era of open APIs. The Asian market is also where the technology companies captured the largest part of the economic value-added of the banking sector in the recent years.

Meanwhile, in Europe almost one-third of the banks surveyed by EIU and Temenos recognize the development of an open banking strategy as their key challenge. According to the banks, the most important threats in 2020 will come from technological companies active in the area of payments, such as PayPal, Alipay, Apple Pay, Square, WorldPay (32 per cent), as well as the global e-commerce companies, such as Amazon, Alibaba, Google, and Facebook (31 per cent).

Service platforms

One particular challenge and threat for the banks are the digital platforms developed by the technology companies. These platforms constitute a distribution channel and an aggregator of various services sometimes loosely related to the field of finance.

The Chinese tech company Tencent build the world’s largest platform of this sort under the brand of the messaging app and payment operator WeChat. In the middle of last year, it provided a variety of services to 1.1 billion users in China and many other Asian countries.

According to the company, 60 per cent of the users open this “super app” at least 10 times a day, and the average daily time spent on the app is more than 66 minutes. The app can be used to make online purchases, including the purchase of airline tickets, to book hotel accommodation, to rent means of transportation, to pay for an apartment, or to order food, including the traditional Chinese dumplings.

The platform therefore attracts huge masses of customers, becoming a very attractive distribution channel for third-party vendors who can join it on a “plug-and-play” basis, that is, without signing any agreements with the operator. It is the customers who ultimately decide whether a given vendor will remain on the platform. The e-commerce platform of the American company Amazon, where several hundred third-party vendors offer their services, operates on a similar principle.

For the time being, banks can only dream of such solutions and such scale of operations. However, as many as 90 per cent of banking executives surveyed by IBM believe that cross-industry platforms will become an important part of the banking sector over the next 10 years, positively impacting revenues, profitability (86 per cent) and customer satisfaction (83 per cent). However, this will be associated with a restructuring of the value chain and a transformation of the existing business models. The difficulty lies in the fact that platform-based banking is a business model based on relationships and data, and not on exercising control. Nevertheless, more and more banks are working to launch their own open platforms. BBVA (Spain, Mexico, United States), Capital One, CitiBank, HSBC or Wells Fargo already have solutions enabling third parties to offer services on the basis of the shared data. Meanwhile, the Singapore-based DBS built a super app dedicated to car owners. It aggregates various services related to the entire life-cycle of a vehicle (purchase, financing, insurance, checkups, loyalty programs, etc.). The largest Polish bank also works on such solutions relating to vehicles and real estate within the framework of the new strategy “PKO Banking Platform”.

Fintechs are also actively developing their own platforms. These include, among others, Kabbage and LendKey. LendKey cooperates with more than 300 banks and credit unions in the United States, offering student loans and home improvement loans in the white-label format, that is, under its own brand. We are also seeing the development of more specialized platforms enabling banks to expand services in the cloud and to utilize fin-tech solutions in the relations with their own customers (e.g. the Canadian FISPAN platform).

Banking applications

One way for the banks to implement fully functional open platforms could be by offering a number of non-financial services (so-called value-added services) within the banking applications.

The largest Hungarian bank, OTP built the Simple platform that aggregates over 40 additional services in a single application. It is integrated with mobile payments, allows users to store digitized loyalty cards and discount coupons, and enables them to make purchases in 3000 e-commerce outlets. This solution is available for OTP customers, as well as for the clients of competing banks.

The success of such an approach and the high demand for value-added services is confirmed by the fact that the application is used by over 700 thousand people, which is almost two times more than the number of users of OTP’s traditional mobile banking app.

The consulting company Deloitte identified more than 250 value-added services offered by banks in Poland. The most popular items on this list include the purchases of public transit tickets, paying for parking spots, booking medical services, and e-government services. PKO BP already has a market share of at least several per cent in the first category.

Studies indicate that value-added services could increase the engagement of occasional users of digital services, including seniors, and could provide new data on customer behavior, which may be important in the process of developing new products. Business models based on value-added services and banking platforms have a good chance for success in Poland, because local banks enjoy high levels of customer trust (67 per cent) compared with the technology companies.

Most traditional banks in the world do not have such a privileged position. They have to quickly decide on their strategy in relation to the phenomenon of platform-based banking. Many of them will be too weak in order to become the owners of platforms and to dictate the terms of participation.

In the best-case scenario, they will be left with the role of active participants or suppliers that are not necessarily offering services under their own brand. Analysts from EY suggest that traditional players should draw upon their advantages, such as the broad customer base, regulatory expertise and established brands, and build platform-based strategies around them, rather than imitating the solutions introduced by the technological companies.

For example, some banks could succeed with platforms linking their retail customers with their corporate customers if they manage to create synergy between these previously separate sets of customers.

However, for the time being, most of the banks functioning within the framework of open banking have difficulty with aggregating a given customer’s accounts at various banks, which would provide added value primarily for the business customers. The problem lies in the resistance to change and the still insufficient spending on innovation. Almost 70 per cent of technology costs are still spent on the outdated legacy infrastructure. And this could make the transformation of business models significantly more difficult.