The effect is that the migratory movements of the citizens of poorer EU member states are improving the situation of those countries, which are already better off – in terms of both demographics and the economy.

There are several reasons for migration. The most urgent and necessary reasons include persecution on ethnic, religious, racial, political, and cultural grounds. These factors can outright force people to leave their country. Wars, as well as the threat of an armed conflict and persecution on the part of the government, can also leave people with no choice other than migration. In the European Union, more than a quarter of the 295 800 asylum seekers who were granted protection status in 2019 came from war-torn Syria, while people from Afghanistan and Iraq were the second and third largest groups, respectively.

At the same time, the ongoing climate change crisis could force an even larger number of people to leave their countries. According to some forecasts, up to 1 billion people could be forced to become “environmental migrants” due to natural disasters or exacerbated extreme weather events.

The number of economic migrants in the world reached approximately 165 million people in 2017.

Demographic and economic changes constitute a separate group of factors driving migration. It is estimated that the number of economic migrants in the world reached approximately 165 million people in 2017.

The so-called push factors of migration include, among others, labor standards, the unemployment rate, and the overall condition of the economy in the given country of origin. There are also the so-called pull factors of migration, which include, among others, higher wages, better employment opportunities, higher living standards, and educational opportunities in the destination country. We can assume that these were the qualities pursued by the millions of migrants from the “new” European Union member states who decided to look for a better life in the “old” EU member states.

The balance and rate of growth of migration

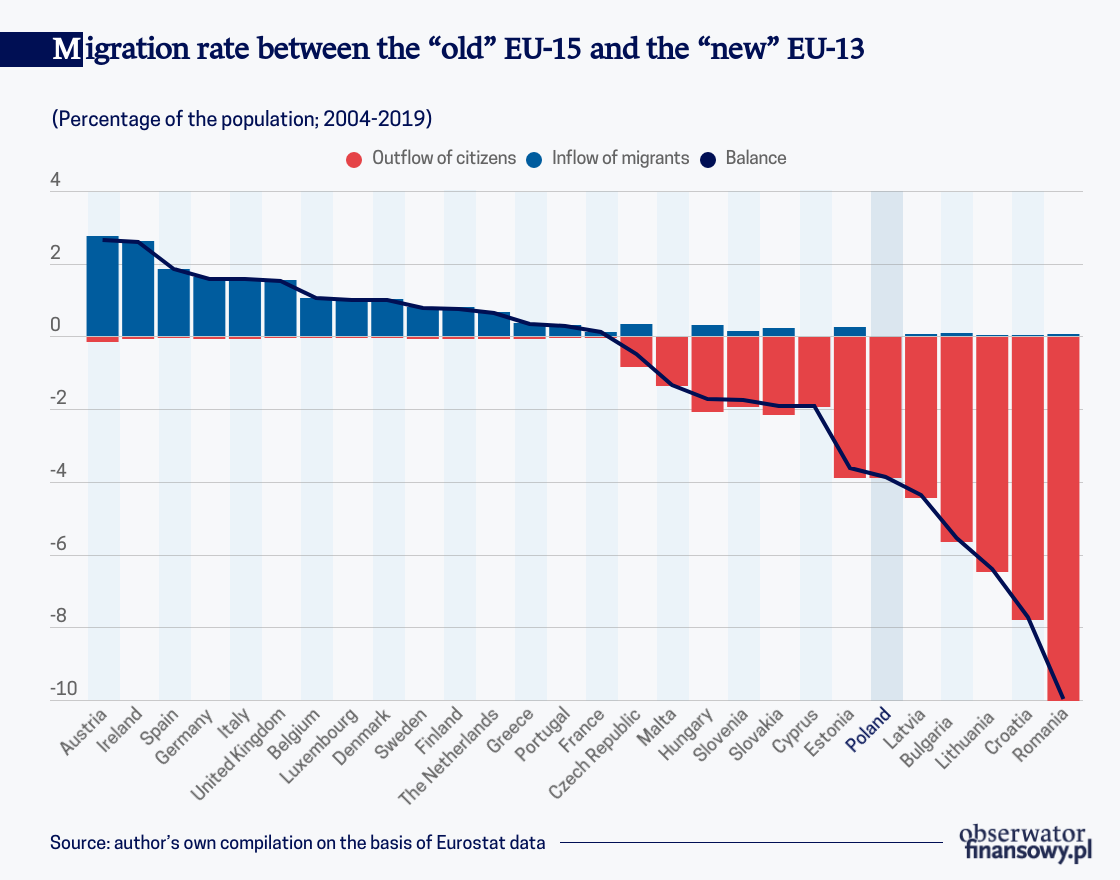

Since 2004, that is, since the biggest enlargement of the European Union, almost 80.4 million people have migrated both temporarily and permanently from the “new” EU member states to the “old” EU member states. This means that more than half of the population of Central and Eastern Europe has lived in the western part of the European Union at least for a short time (52.2 per cent of the overall population of the EU-13 countries).

For comparison, the percentage of citizens who have moved from the “old” EU member states to the EU-13 countries only accounted for 0.51 per cent of the total population of the EU-15 countries. Thanks to the mass migrations, the population of the “old” European Union member states, which is by far greater than that of the “new” EU member states – amounting to 425 million people, on average, in the period 2004-2019 – increased by 1.26 per cent, on average, over the course of 16 years. This is more than 5.3 million annually. Over the same period of time, the number of citizens from the EU-15 countries in the “new” EU member states increased by 118 000 persons, or 0.11 per cent of the population of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. As a result, while the population of the “new” EU member states decreased by 2.1 million compared to 2004 due to migration to the EU-15 countries, the “old” EU member states grew by 23.6 million citizens of the EU-13 countries.

The migration volumes are characterized by a certain degree of seasonality – roughly every three years there is a visible phenomenon of migrants postponing their decision to go abroad, which applies to both temporary and permanent migration.

This cyclicality of migrations is not detached from the economic circumstances. This is clearly evident when we take a look at the periods of crises. In times of economic downturns, the tendency to go abroad clearly decreases. However, it is impossible to precisely predict the exact date of a recession in order to assess the risk of going abroad.

Impact on family-related decisions

Based on the figures from the Eurostat database, in our analysis we explore, firstly, whether migration has a significant impact on the number of marriages, and what the total fertility rate is.

The results of the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) analysis indicate that the emigration of citizens from the EU-13 countries has a significant impact on their total fertility rate and their propensity to get married. However, the strength of this impact is not the same for all the migration destinations among the “old” EU member states. Generally speaking, EU member states can be divided into two main categories.

On the one hand, there are countries in which the decision to formalize a relationship typically goes hand in hand with the decision to have children. On the other hand, there are also countries where such a trend and such a relationship are not observed.

The first group includes 11 countries of the EU-15. Among them, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom are countries where migrants from EU-13 countries do not typically wait for a long time before starting a family. In the remaining 7 countries from that group – i.e. Ireland, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Germany – migrants typically decide to get married and have children somewhat later; however, this usually happens simultaneously – within the same year.

In the second group of EU-15 member states, we have four countries where migrants tend to formalize their relationship first, and only then – most frequently in the following year – decide to have children. These countries include Portugal, Greece, the Netherlands, and Austria.

The impact on local demographics is also visible in the EU-13 countries that received migrants from the “old” EU member states. The citizens of the “old” EU member states who decided to settle in the Czech Republic, Croatia, Lithuania, Hungary, and Poland, typically decide to formalize their relationships and to have children shortly after their arrival. Foreigners from the “old” EU member states choose to have children before marriage more frequently in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Malta, which is reflected in the total fertility rates in these countries.

Meanwhile, migrants who came from the EU-15 countries to Estonia and Latvia more frequently prefer to marry before having children. As a result, migration from the West to the East improves the fertility rates to a limited extent.

Impact of migration on economic growth

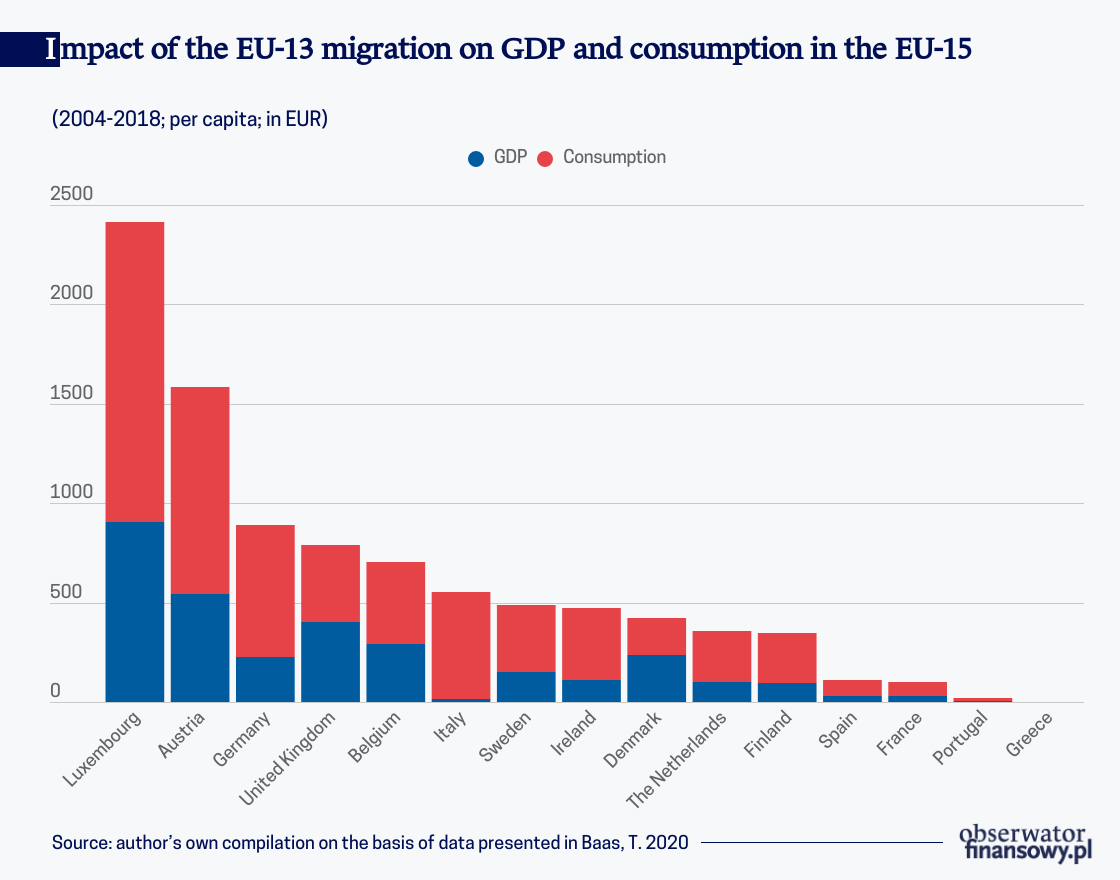

In addition to demographics, the impact of migrations can also be viewed from the perspective of a given country’s affluence.

Since 2004, the GDP per capita of the “old” EU member states has increased by an average of EUR 618 due to the migration of citizens from EU-13 countries to the EU-15 countries. The biggest GDP gains have been recorded in Luxembourg (increase of EUR 2 420 per capita), Austria (EUR 1 580 per capita), Germany (EUR 900 per capita), and the United Kingdom (EUR 800 per capita).

During this time, economic migrants from Central and Eastern Europe contributed significantly to the GDP growth. The “old” European Union member states gained even more due to the additional consumption of the migrants, which was the main driver behind the additional increase in the level of affluence of the EU-15 countries in the years 2004-2018.