German automotive industry at a crossroads

Kategoria: Business

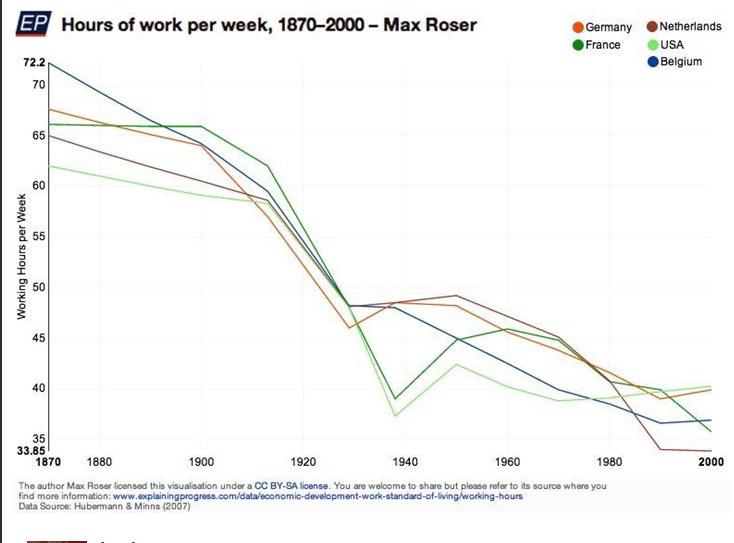

This Great Graphic was tweeted by Ian Bremmer, but it comes from Max Roser. It shows the work week, measured in hours going back to 1870 for several countries, including the US, Germany and France. The data only runs up to 2000. At the risk of turning a necessity into a virtue, perhaps the most recent data would be skewed by the two downturns in the first decade of the new century.

If one agrees that the disparity of income and wealth poses economic, political and moral challenges, re-thinking the length of the work week may be among the least intrusive ways to address it. Moreover, given the extent of labor-saving technological progress, there is no „natural” reason why the number of employment opportunities an economy generates should have any relationship to size of the labor force.

Yet in someways, high income societies are moving in the opposite direction–raising retirement ages. This is obviously meant to reduce the cost of social security outlays. However, it risks aggravating the generational issue. The older generation stays in their positions for longer, blocking the ascendancy of the next generation.

The link between work and consumption was previously regarded as sacrosanct because it was critical to maintaining market discipline. No work, no food. However, given that government transfers are the fastest growing part of household income in the US, and there is even more extensive social protection in Europe, the link between work and consumption has already been loosened. That Rubicon has been crossed. The productive capacity is so large that society needs people to consume more than it needs people to work. Indeed, wealth and income disparities are much greater than the disparity of consumption.