German automotive industry at a crossroads

Kategoria: Business

Wygląda na to, że debata na temat euro przybiera kształt podobny do tej, która poprzedziła utworzenie wspólnej unii walutowej. Coraz więcej publikacji dotyczy kwestii fundamentalnych związanych z eurostrefą.

Legatum Institute opublikował raport pt. „Can the Euro survive?”, w którym sugeruje, iż kraje PIIGS mogłyby szybciej wydźwignąć się z kryzysu, gdyby wyszły z unii walutowej. W innym wypadku zapowiadane przez Unię oszczędności budżetowe spowodują długotrwałą recesję.

A second area where extraordinarily large imbalances have emerged in Europe’s periphery has been in the housing markets of Ireland and Spain. Fuelled by easy access to global credit, as well as by the ECB whose one-size-fits-all interest rate policy kept interest rates too low for too long for Europe’s periphery, Ireland and Spain experienced housing bubbles that make that experienced in the United States pale. (…) The bursting of the housing bubbles in Ireland and Spain has been a primary driver in the dramatic deterioration in their public finances. It has also been the primary factor in the rise in unemployment in Ireland and Spain to their present levels of around 13 percent and 20 percent respectively.

Autorzy raportu twierdzą, że finanse krajów peryferyjnych (Grecji, Hiszpanii, Portugalii i Irlandii) są niemożliwe do naprawienia. Nie pomogą zapowiadane poprawki do traktatu ani zaostrzenie polityki fiskalnej eurostrefy. Ponadto ratyfikacja traktatu wymaga czasu, którego brakuje w czasie obecnego kryzysu.

While the treaty modifications now being proposed would have had great merit when the Euro was launched in January 1999, how relevant they are today at a time when the periphery’s public finances have been compromised beyond repair and when there is every indication that the periphery’s crisis is deepening is questionable. While the periphery’s sovereign debt crisis is playing out in real time, past experience would suggest that treaty modification, which requires unanimous ratification by all European Union members, will take years to effect. In addition, it would appear that the proposed reforms overlook the fact that the major part of the periphery’s budget deficits is primary in nature.

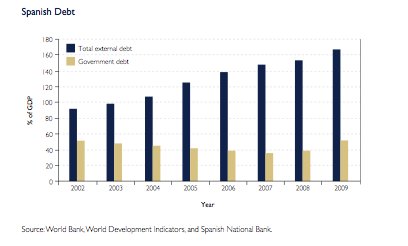

Nie pomoże też częściowa redukcja długu państw peryferii. W odróżnieniu od innych tego typu opracowań raport szczególnie zwraca uwagę na wpływ zadłużenia zewnętrznego. Wartość kredytów udzielonych deweloperom przez hiszpańskie (połączone nierozerwalnie z europejskim systemem bankowym) jest odpowiednikiem 45 proc. PKB tego kraju.

As such, even if the debt of the periphery were to be substantially written down, the periphery would still be left with very large budget deficits. And reducing these very large budget deficits to sustainable levels would still involve very deep recessions if such an exercise were attempted within the straitjacket of continued Euro membership.

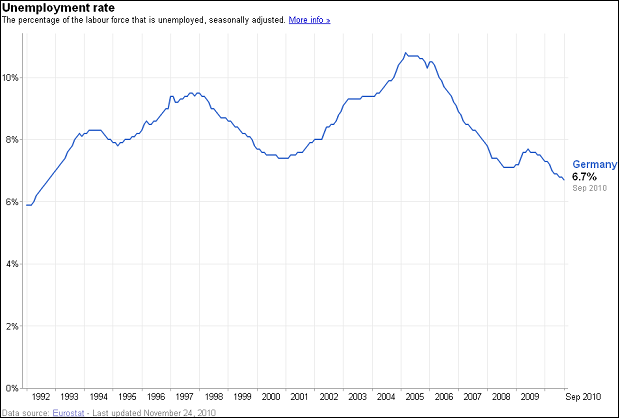

Mimo wszystkich problemów wbrew pogłoskom Niemcy raczej nie zechcą wycofać się z euro. Z wykresu można dowiedzieć się, że stopa bezrobocia w Niemczech wynosi około 6 proc. (i jest najniższa w Unii) i że wciąż spada.

Surprisingly, the only sector that did not experience an increase in its debt level during that period was the government sector, which saw its debt decline from 72 to 68% of GDP. Ireland and Spain, two of the countries with the severest government debt problems today, experienced the strongest declines of their government debt ratios prior to the crisis. These are also the countries where the private debt accumulation was the strongest.

European leaders probably recognized then that their banking system was overleveraged, and they may need to cut government programs (or raise taxes) to shoulder new private debt from the the private banking system.

In other words, they never believed, nor could you have rationally believed, that there was really a plan to for the Europeans to „austere” their way out of a recession.

Ale grecka i irlandzka gospodarka podobne są do nowozelandzkiej; dlaczego więc tam sytuacja ekonomiczna wygląda na spokojną pyta Prof. Eric Crampton z University of Canterbury?

All three have high net foreign liability positions, liabilities are highly concentrated through banks who are borrowing overseas, all three have experienced some form of housing boom and lift in consumption, and finally all three appeared to have a relatively strong fiscal position before the GFC before moving into fiscal deficits after the shock. And yet (so far) while the Irish and Greek economies and banking systems have collapsed, New Zealand’s has been fine.

Jednak Nowa Zelandia sprywatyzowała wszystkie banki, a jej stopy procentowe są płynne. I większość długu została zdenominowana w nowozelandzkim dolarze. (Na ten temat także Matt Nolan).

Jeden z dobrze poinformowanych ekonomistów-analityków na temat sytuacji gospodarczej Chin Vitaliy Katsenelson uważa, że wzrost gospodarczy Chin oparty jest na nietrwałych podstawach. Chiński rząd zarządza kapitałem tak by realizować krótkoterminowe cele. Katsenelson przytoczył przykład budowania osiedli mieszkalnych, z których nikt nie mieszka. Jedno z nich, Ordos, które do dziś stoi puste, dla 1,5 mln mieszkańców powstało w środkowej Mongolii.

The vacancy rate on commercial real estate in China is fairly high, but they still keep on building new office buildings because they think they will always grow. So therefore as long as they keep building, that activity will be registered as growth, until they stop. And when they do stop, they’ll drown in overcapacity, and they won’t be building new skyscrapers for a very long time.

Katsenelson nazywa China superbańką.

Dla tych ekonomistów, którzy nie ufają statystykom chińskim poleca inną metodę obserwacji gospodarki. Przylądanie się danym: zużycia elektryczności (spadła w czasie recesji), sprzedaży żywności w restauracjach fast-food, ilość towarów transportowanych koleją a także sprzedaży amerykańskich i europejskich firm w Chinach.

Opracował Tomasz Pompowski