Generatywna sztuczna inteligencja a wzrost gospodarczy

Kategoria: Trendy gospodarcze

Wśród wielu informacji dotyczących wykupu Irlandii, które przebijają się z opóźnieniem jest wiadomość o możliwej fuzji tamtejszych banków. To bardzo ważna wiadomość, bo przecież mówiło się o tym, że „instytucje zbyt duże, by upaść” mogą doprowadzić do kolejnego kryzysu.

Ireland’s banks will be pruned down, merged or sold as part of a massive EU-IMF bailout taking shape, the Irish government said.

Międzynarodowy Fundusz Walutowy domaga się, by Irlandia zmniejszyła zasiłki dla bezrobotnych i obniżyła wysokość płacy minimalnej. A także egzekwowała wymóg poszukiwania pracy. Irlandia wprowadzi także znaczne ułatwienia dla biznesu:

The Government’s four-year plan will include measures to drive down costs to business in order to increase competitiveness, the Government’s economic adviser Alan Ahearne disclosed. He said the plan would seek reductions in the costs of electricity, waste disposal, broadband and professional services such as legal fees.

Istnieje trudność z określeniem wysokości zadłużenia Irlandii, na którą wskazują prof. Simon Johnson i prof. Pat Boone. Tłumaczą oni w jaki sposób PKB Irlandii (m.in. była rajem podatkowym dla zagranicznych korporacji) różni się innych państw:

When we adjust Ireland’s figures accordingly, the situation is dire. The budget deficit was about 17.9 percent of G.N.P. in 2009, and based on European Commission projections (and assuming the G.N.P.-G.D.P. gap remains the same) it will be roughly 14.6 percent in 2010 and 15.1 percent in 2011, while the debt-to-G.N.P. ratio at the end of this year is expected — by our calculation — to be 97 percent, and 109 percent at the end of 2011. These numbers make Ireland look similarly troubled to Greece, with a much higher budget deficit but lower levels of public debt.

Some news reports are currently using a higher number for Ireland’s debt, implying that the country owes 10 times its GDP; this is based on misreading the statistics regarding off-shore financial transactions that are run through Ireland. This misunderstanding will be cleared up when the Ireland-IMF-EU package is announced.

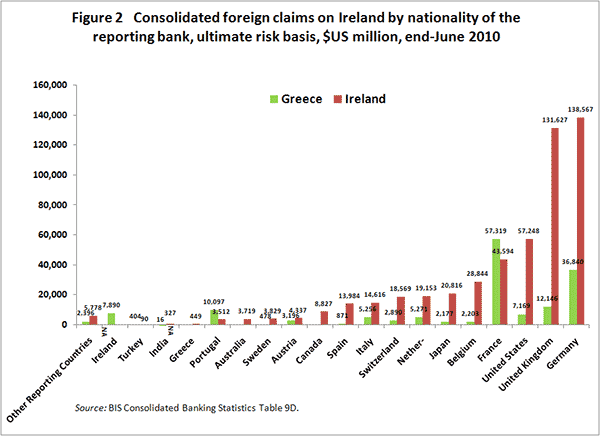

Prof. Jacob Kierkegaard z Peterson Institute for International Economics ukazuje w jakim stopniu irlandzkie długi rzutują na europejskie banki – gdyby Irlandia zbankrutowała, straciłyby one ponad 500 mld euro. Na wykresie doskonale widać jak świat banków przypomina naczynia połączone. Najbardziej ucierpiałyby niemieckie i brytyjskie banki.

(…) the foreign bank claims (24 countries reporting to the BIS) on Ireland at over $500 billion are more than three times the scale of total claims against Greece. The hypothetical implications of even an isolated (i.e., without contagion) Irish economic collapse would thus as a first approximation be considerably larger than was the case for Greece. (…) German and British banks alone account for over half the total exposure to Ireland. Contrary to Greece, US banks have a sizable Irish exposure, too, according to the BIS data. Getting substantial IMF funding for Ireland should therefore not be an obstacle, given the US influence here.

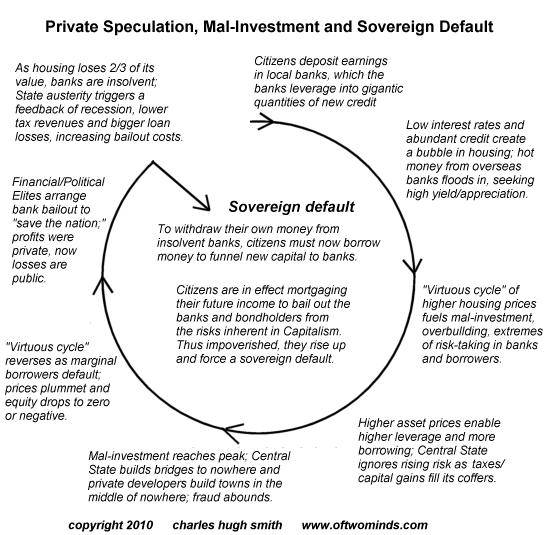

ZeroHedge via OfTwoMinds przedstawia dynamikę zadłużenia Grecji, Irlandii i innych państw – od bańki na rynku nieruchomości do bankructwa rządów.

Prof. Brad DeLong pokazuje jak po II wojnie światowej zaistniały warunki, aby państwa prowadziły aktywną politykę stabilizacyjną. Zniknęło lobby zainteresowane stabilnym pieniądzem, które miało wielką siłę polityczną, grupy społeczne którym najbardziej zależało na minimalizowaniu bezrobocia zdobyły prawo głosu, zwiększył się poziom wiedzy ekonomicznej. Dziś jednak znowu zdaniem DeLonga zanikło zrozumienie faktu, którzy akceptowali ekonomiści od Keynesa po Friedmana, że rządy muszą dokonywać strategicznej interwencji na rynkach finansowych, by utrzymać poziom wydatków w gospodarce.

Why are the principles of nominal income determination, which I thought largely settled since 1929, now being questioned? Why is the idea, common to John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, Knut Wicksell, Irving Fisher, and Walter Bagehot alike, that governments must intervene strategically in financial markets to stabilize economy-wide spending now a contested one?

O błędnych założeniach ekonomistów na przestrzeni dziejów i obecnym kryzysie jako ich konsekwencji pisze prof. Paul Krugman. Trudność w pogodzeniu racjonalnej, możliwej do zmatematyzowania mikroekonomii z pełną behawioralnych zagadek makroekonomią doprowadziła do obecnej sytuacji: Wieków Ciemnych makroekonomiii

One must count on the government to ensure more or less full employment; only once that can be taken as given, do the usual virtues of free markets come to the fore.

Economists were bound to push at the dividing line between micro and macro – which in practice has meant trying to make macro more like micro, basing more and more of it on optimization and market-clearing. (…) it was probably inevitable that a substantial part of the economics profession would simply assume away the realities of the business cycle, because they didn’t fit the models.

The result was what I’ve called the Dark Age of macroeconomics, in which large numbers of economists literally knew nothing of the hard-won insights of the 30s and 40s – and, of course, went into spasms of rage when their ignorance was pointed out.

Worthwile Canadian Initiative jest zdania, że poszukiwanie złotego środka – doskonałej polityki monetarnej, którego zdają się oczekiwać prof. Krugman i prof. DeLong, jest skazane z góry na niepowodzenie.

W Stanach Zjednoczonych trudno o optymizm co do gospodarki. Sprzedaż nowych domów spadła o 28 proc. w październiku 2010 r. w stosunku do poprzedniego roku – zauważa Big Picture.

This is down from 308 thousand in September. „This is 8.1 percent below the revised September rate … and is 28.5 percent below the October 2009 estimate of 396,000.”

Prof. Becker jest przeciwny polityce ilościowego łagodzenia. Ale jego prognoza (m.in. spadek wartości dolara do euro) jeszcze się nie spełniła.

Central banks and other participants in currency markets are expecting an eventual significant increase in prices in the United States. This is why they have been trying to reduce their holdings of dollar-denominated assets that would decline in real value with inflation. These efforts in turn lower the value of the dollar relative to the euro, yen, and other currencies. Until the inflation rate actually increases by a lot, this reduction in the exchange value of the dollar reduces the prices of US goods in the international market.(…) once inflation actually takes off, the process will tend to be reversed: demand for US exports would decline, and American demand for imports would go up.

Równie konserwatywny Money Ilusion z kolei przewrotnie sugeruje, iż August von Hayek doradziłby politykę ilościowego łagodzenia Europejskiemu Bankowi Centralnemu. Na ten temat także Buttonwood. I polemika MacroMarketMusings.

Opracował: Tomasz Pompowski