Tydzień w gospodarce

Kategoria: Raporty

Egipskie protesty się zakończyły. Ale ekonomiści poszukują ich gospodarczych korzeni. Jednym z nich jak wspominał parokrotnie Obserwator i Metablog są podwyżki cen żywności. Czy jest to jedynie nieprzewidziany skutek polityki ilościowego łagodzenia (ucieczka inwestorów od dolara i papierów wartościowych do zasobów takich jak zboże, kukurydza czy bogactwa naturalne: metale szlachetne etc) czy także tzw zielonej energetyki? Tak sugerował były sekretarz Departamentu Rolnictwa Ed Schafer w rozmowie z radiem Bloomberg.

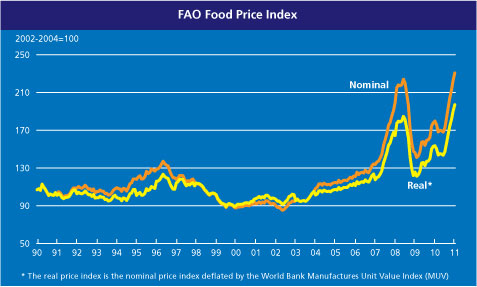

Według ONZ 10 proc. światowej produkcji ziarna zbożowego (także kukurydzy) przeznaczone jest na produkcję etanolu. W styczniu 2011 w porównaniu z poprzednim miesiącem indeks Food Price FAO wzrósł 3-4 proc. – utrzymał tendencję wzrostową, którą można zaobserwować od 7 miesięcy. Wzrósł zarówno realny jak i nominalny indeks.

The FAO Food Price Index rose for the seventh consecutive month, averaging 231 points in January 2011, up 3.4 percent from December 2010 and the highest (in both real and nominal terms) since the index has been backtracked in 1990. Prices of all the commodity groups monitored registered strong gains in January compared to December, except for meat, which remained unchanged

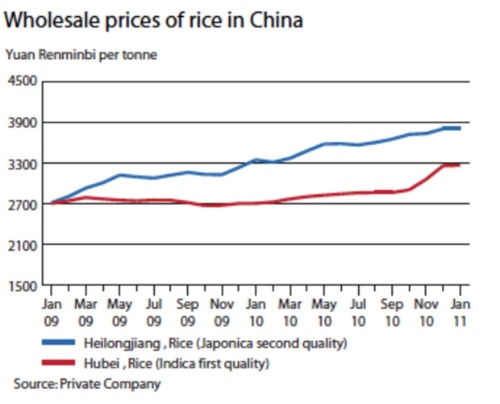

Podobnie stopniowo, ale jak dotąd niezmiennie, wzrastają ceny żywności w Chinach – według styczniowej edycji Global Food Price Monitor. Cena mąki pszenicznej wzrosła w styczniu 2011 o 16 proc. w porównaniu z analogicznym okresem w ub. roku. FAO widzi możliwość dalszego wzrostu jeśli na terenach uprawnych utrzyma się susza.

In China, prices of main staples rice and wheat have been rising in the last months. Prices of rice have increased markedly in the second half of 2010, in particular those of the Indica variety, the most consumed by the low income population. Prices stabilized in January with the arrival of the 2010 “late-rice crop” harvest into the markets. In the main producer area of Hubei, wholesale prices of Indica rice were quoted at CNY 3260 per tonne in January 2011, some 20 percent higher than a year ago.

Prices of wheat flour, have also risen significantly in the past two months and by January 2011 the national average price was 8 percent higher than in November and 16 percent above the level one year ago. Dry weather in the main wheat producing northern provinces has raised concern about prospects for this year’s crop supporting the rapid increase in prices.

Wzrost cen zasobów i żywności powinien według makroekonomisty Gavina Daviesa zacząć interesować banki centralne.

the commodity price shock would have a permanent effect on input prices in the developed economies, and it would not be appropriate for the central banks to ignore this shock. In fact, if they ignored it, they would simply be accommodating a permanent inflation shock to the system, which is what they did in the inflationary 1970s.

Szef IMF Dominique Strauss-Kahn ostrzegł 1 lutego przed nadmiernym wzrostem inflacji w Azji.

He said that Asian economies may need to raise interest rates and slow the rise of property prices and money inflow from Western countries, and that while Asian central banks have been raising interest rates to deal with inflation, „more may be needed.” (…) „The risk of overheating is certainly a strong one, which means many countries should be tightening where output gaps have been closed, or will be closed,” he said.

W Azji wzrastają ceny m.in. papryki chili, produktu, który jest codziennym składnikiem potraw ubogich – podkreśla ekonomista William Pesek.

It’s about social stability in emerging economies that suffer from an underappreciated vulnerability. East Asia is home to a critical mass of those surviving on less than $2 a day. For families, surging costs for chili peppers, rice and cooking oils are a desperate issue.

Zapowiedź 70 proc. wzrostu cen niektórych produktów żywnościowych (owoce i warzywa – jak mówią niektóre źródła nawet ponad 200 proc.) pojawiła się w Australii. Tutaj jednak straty spowodowały największe od II wojny światowej powodzie i cyklon. Niemniej Australijczycy biorący udział w dyskusji pod artykułem nt wzrostu cen twierdzą, że jeszcze przed powodzią ceny warzyw i owoców wzrosły o 15 proc.

So vegetable and fruit prices rose by 15% before the flood. Seems to me that its about time that the government bureau of statistics need to get a lot more transparent about where their CPI figures come from. They certainly aren’t containing my inflationary expectations but it seems that appearances are all that matter.«

Czy istotnie są to pierwsze oznaki, iż inflacja zaczyna wymykać się spod kontroli. Przypuszczalnie za wcześnie na takie daleko idące oceny. Jednak warto zapoznać się z poglądami tych ekonomistów, którzy optują za wyjaśnieniem obecnych turbulencji gospodarczych przy pomocy deflacji oraz tych co raczej uważają, iż jest to zwiastun deflacji.

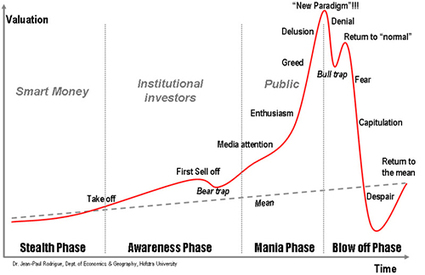

Nicole Foss już w 2008 r. opisywała kryzys mianem deflacji. Na podstawie m.in. jej tekstu Resurgence of Risk powstał Overdose jeden z najciekawszych dokumentów nt obecnego kryzysu. W swoim artykule dowodzi, że poważnym problemem Fed jest brak gotówki raczej niż jej nadmiar. I dodaje, że kryzys uruchomił mechanizm ograniczenia kredytu, który skutkuje niemożnością spłacenia zaciągniętego długu. Pozostaje ratunek w postaci sprzedaży akcji i innych papierów wartościowych, by móc wywiązać się z zobowiązań finansowych. Ale nagła sprzedaż wiąże się ze spadkiem cen tych zasobów. A ostatecznym efektem tego procesu, jak pisze Foss, jest katastrofa deflacji.

There is actually very little real cash out there relative to credit. The „sudden demand for cash” is in fact the world’s biggest margin call to date. (…) It is said that humans have only two modes – complacency and panic, and markets, being a human construct, are no exception. (…) Actual cash is in short supply,

When the burden becomes too great for the economy to support and the trend reverses, reductions in lending, spending and production cause debtors to earn less money with which to pay off their debts, so defaults rise. Default and fear of default exacerbate the new trend in psychology, which in turn causes creditors to reduce lending further. A downward „spiral” begins, feeding on pessimism just as the previous boom fed on optimism. The resulting cascade of debt liquidation is a deflationary crash. Debts are retired by paying them off, „restructuring” or default. In the first case, no value is lost; in the second, some value; in the third, all value. In desperately trying to raise cash to pay off loans, borrowers bring all kinds of assets to market, including stocks, bonds, commodities and real estate, causing their prices to plummet. The process ends only after the supply of credit falls to a level at which it is collateralized acceptably to the surviving creditors.

Ekonomista Gonzalo Lira przekonuje, że jednak rezultatem obecnego kryzysu będzie hyperinflacja. Dr Lira dowodzi, że okres stagflacji w latach 1979-80 najlepiej wyjaśnić zjawiskiem hyperinflacji. I próbuje zastanowić się czego można sie zeń nauczyć?

Could the ‘79 Oil Shock, and subsequent bout of stagflation, be better understood as a period of incipient hyperinflation? (…)

Pisząc o obecnym okresie Lira uważa, że początkowo wzrastająca inflacja będzie traktowana jako zjawisko pozytywne.

Increased inflation (…) will be considered a good thing: Because of the current deflationary recession we are in, any pick up in the inflation index will be interpreted as a pick up in the overall economy.

W końcu jednak gdy sięgnie ona 15 proc. jak w marcu 1980 zacznie być postrzegana jako problem.

Eventually, however, as inflation continues to rise but the jobs market doesn’t really improve, the current American economy will wake up and find it has reached the exact same point that was reached back in March of 1980—a 15% annual inflation rate.

Jednak w przeciwieństwie do ówczesnego szefa Fed Volckera, obecny, Bernanke nie może podnieść stóp procentowych. Gdyby je podniósł, zagroziłby podtrzymywanym tanim pieniądzem instytucjom finansowym…

But here is the key difference: Ben Bernanke and the Federal Reserve cannot raise rates to reign in incipient hyperinflation, like Volcker did in ‘79. (…), Bernanke simply does not have the room to maneuver, insofar as the Fed funds rate is concerned. (…) if he did, he would wipe out all the Too Big To Fail banks, and break the Treasury of the U.S. Federal government, both of which depend on the Fed’s cheap money as completely as if it were oxygen.

W 1979 r. ten problem nie istniał. Volcker podniósł stopy płacąc za to wzrostem bezrobocia o 4 proc. A obecna, oficjalna stopa, sięga 10 proc. przy miękkim kredycie.

Back in 1979, Volcker didn’t have this constraint. He could raise rates—but even so, he paid for it with 400 basis points of unemployment. (…) Bernanke cannot raise rates in order to stop a run on Treasuries, stop a run up on commodities, and stop incipient hyperinflation: The economy is too weak.

Według Dr Liry Bernanke boi się deflacji do tego stopnia, że próbuje wywołać inflację. Jest przekonany, że gospodarka potrzebuje zastrzyków płynnosci i taniego pieniądza. I że inflacja oznacza wzrost i zmniejszenie długu federalnego.

Bernanke thoroughly believes that only liquidity injections and cheap money can save the economy—he is looking for inflation. He is so terrified of the American economy circling the deflationary drain, that he is deliberately going in the other direction: He is trying to cause inflation. (…) He is convinced that inflation means growth—the opposite of deflation. He is convinced that inflation will signal that the economy is recovering, and that the Federal Debt will be inflated away, and therefore not break the Federal government finances.

Dlatego według dr Liry istnieje niebezpieczeństwo, że Fed może uruchomić mechanizm hyperinflacji.

This is why Bernanke is set up to take a hit from hyperinflation: If and when there is a run on Treasuries, and a subsequent run up of commodities, at least initially, the Federal Reserve under Ben Bernanke will not only do nothing, they will encourage this situation. The Fed and its current leadership will interpret this rise in the CPI number as an indication that “We are on the road to recovery!”

Przypuszczalnie jedną z możliwych konkluzji tej debaty formułuje w swojej bardzo ciekawej książce The Great Reflation: How Investors Can Profit from New World of Money.

…inflation and deflation are two sides of the same coin with the difference being in the timing. Too much inflation always ends in deflation, and deflation paves the way for the next inflation so long as the central bank is able to reflate.”

oprac. T.Pompowski