Generatywna sztuczna inteligencja a wzrost gospodarczy

Kategoria: Trendy gospodarcze

Wartość europejskich zasobów i PKB razem nie pokryje długów i innych zaciągniętych zobowiązań finansowych państw Unii. Inaczej mówiąc realna gospodarka eurostrefy jest zbyt mała, by dofinansować zubożały system bankowy i nadwyrężone budżety państw.

Prof. Kenneth Rogoff uważa, że Europa znajduje się dopiero na półmetku kryzysu. I porównuje problem Europy do kryzysu latynoamerykańskiego w latach 80. Przewiduje więcej wykupów: Portugalia, Hiszpania. I twierdzi, że Europejski Bank Centralny popełnił błąd zamieniając dług prywatny na dług publiczny.

What Europe and the IMF have essentially done is to convert a private-debt problem into a sovereign-debt problem. Private bondholders, people and entities who lent money to banks, are being allowed to pull out their money en masse and have it replaced by public debt. (…) By nationalizing private debts, Europe is following the path of the 1980’s debt crisis in Latin America. There, too, governments widely “guaranteed” private-sector debt, and then proceeded to default on it. Finally, under the 1987 Brady plan, debts were written down by roughly 30%, four years after the crisis hit full throttle.

Prof. Barry Eichengreen określa „wykup” Irlandii mianem katastrofy. Nakaz cięć wydatków publicznych i podniesienia podatków, by sfinansować dług doprowadzi jego zdaniem do spirali narastającego długu. Prof. Eichengreen obawia się, że nastąpi deflacja długu opisana przez prof. Irvinga Fischera z Yale w analizie Wielkiego Kryzysu.

Ekonomista dr Kevin O’Rourke przedstawia rozwiązanie alternatywne, które można było zastosować w Irlandii zamiast jak pisze „wykupować zagranicznych inwestorów”.

Swapping debt for equity in a coordinated fashion across Europe would show ordinary people that Europe is on their side; but like the PLO of old, the European Union never misses an opportunity to miss an opportunity. It could have provided a means of kick-starting a new post-crisis growth strategy based on investment in the infrastructures we will need in the future; instead it has transformed itself into a mechanism for forcing pro-cyclical adjustment onto countries that are already sinking.

Zdaniem części obserwatorów na Wall Street Europę czeka poważny kryzys związany z utratą płynności finansowej, ponieważ jej system bankowy urósł nieproporcjonalnie w stosunku do wielkości jej gospodarek. Inwestorzy są także świadomi, że kolejny etap kryzysu Europy to katastrofa demograficzna. Państwa opiekuńcze z powodu braku pracowników nie będą w stanie wywiązać się z zaciągniętych zobowiązań emerytalno-rentowych a także opieki zdrowotnej, jeśli nie przeprowadzą koniecznych reform.

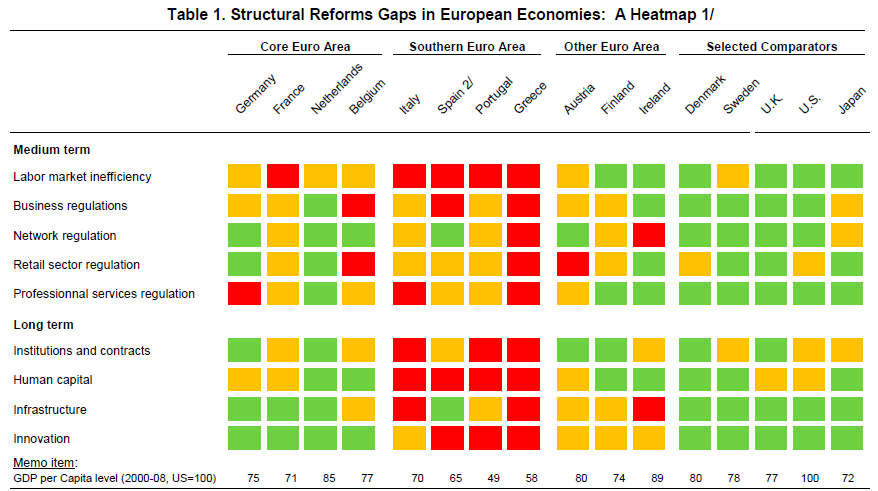

Tabela 1 (via Alea blog) braki reform strukturalnych europejskich gospodarek:

Bruno Leoni Institute publikuje krytykę raportu dr Mario Monti, byłego komisarza Unii ds konkurencji, na temat ponownego otwarcia dla wspólnego rynku. Raport powstał na prośbę przewodniczącego Komisji Europejskiej Jose Manuella Barroso. Ekonomiści Instytutu wskazują na dwa poglądy – „liberalizację” i „harmonizację”, które od początku integracji ścierają się w Unii.

We must also note that the trend towards liberalization coexisted–perhaps ever since the establishment of the EU–with an opposed trend towards harmonization. Thus, if on the one hand there was the attempt to defang the interventionism at the national level (as witnessed by the several markets which were partially opened to competition only–or mainly–thanks to the effects of a EU Directive), of the other hand the attempt emerged to integrate the several national regulation–particularly in the taxation realm–as well, to secure a more effective implementation of public policies and to pursue the EU’s „general interest.” whatever this may be.

Wydaje się, że wśród ekonomistów Unii przeważa jednak dziś tendencja do liberalizacji. Bo jak pisze David Goldman państwa osi Unii ze względu na groźbę horrendalnych strat nie mogą sobie pozwolić na odejście od peryferii.

Spain is key, given that it accounts for 11% of Euro-area GDP (65% larger than Portugal, Ireland and Greece) and that there are $876bn of foreign bank assets in Spain according to the BIS (75% of which are accounted for by European banks, with 40% – around $340bn – held by German and French banks alone). We note that recently CDS spreads have risen to previous peak (with bond spreads not far behind).

Jednak zależności są jeszcze głębsze:

(…) a Fitch ratings report (…) that Spanish banks are cherry-picking bad loans out mortgage-backed securities they have issued and putting them on their own books. Why take the losses? Because otherwise the securities would be downgraded and no longer qualify as loan collateral at the European Central Bank, which is the only institution that wants to lend money to PIIGS’ banks.

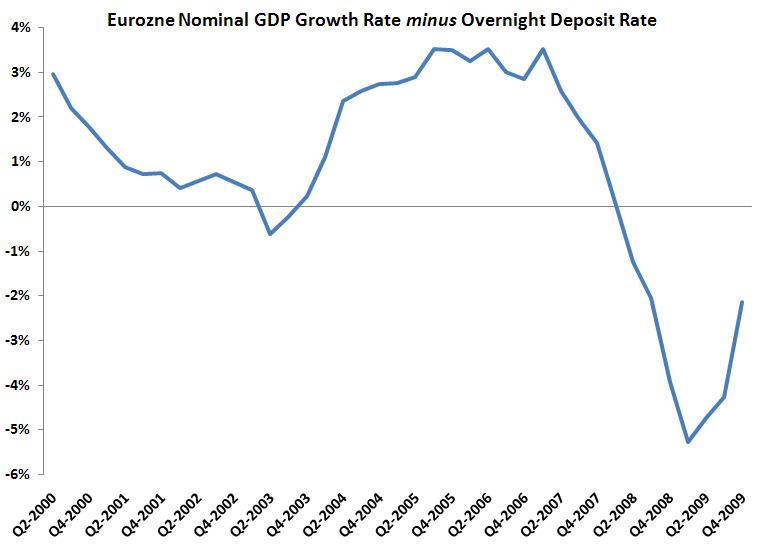

Macromarketmusings blog wyciąga cztery wnioski z kryzysu europejskiego. Jednym z nich jest fakt, iż bank centralny odgrywa olbrzymią rolę w stabilizacji sytuacji makroekonomicznej.

The sharp decline in the Eurozone’s aggregate demand was avoidable had the ECB really tried to stabilize it. Instead, the ECB mistakenly looked to low short-term interest rates as an indicator of loose monetary policy and became convinced it was doing enough.

The ECB policy rate should not deviate too far from the aggregate demand growth rate otherwise monetary policy is either too loose (the policy rate is significantly below the total spending growth rate) or too tight (the policy rate is significantly above the total spending growth rate).

Matthew Yglesias sądzi, że kryzys utraty płynnosci finansowej jaki dotyka Unię nie grozi USA. Dlaczego? Bo – jak tłumaczy obrazowo – Irlandii może zabraknąć euro – bo euro drukowane jest w Belgii. Peru może zabraknąć dolarów – bo dolar drukowany jest w Waszyngtonie. Ale USA nie zabraknie dolarów bo mogą je łatwo dodrukować. Istnieje więc groźba, ale inflacji, ta zaś jest obecnie na bardzo niskim poziomie.

oprac. T.Pompowski